Legal for recreational use Legal for medical use Illegal

Cannabis is currently legal for medical and industrial uses in Italy, although it is strictly regulated, while it is decriminalized for recreational uses. In particular, the possession of small amounts of marijuana for personal use is a civil infraction. The possible sanctions for possession vary from the issuing of a diffida to first offenders, which is an injunction not to use the drug again; to the temporary suspension of certain personal documents (e.g. driving licenses) for repeat offenders. Conversely, the unauthorized sale of cannabis-related products is illegal and punishable with imprisonment, as is the unlicensed cultivation of cannabis, although recent court cases have effectively established the legality of cultivating small amounts of cannabis for exclusively personal use. The licensed cultivation of cannabis for medical and industrial purposes requires the use of certified seeds; however, there is no need for authorization to plant certified seeds with minimal levels of psychoactive compounds (a.k.a. cannabis light).

Historical background

Main article: History of cannabis in ItalyThe cultivation of cannabis in Italy has a long history dating back to Roman times, when it was primarily used to produce hemp ropes, although pollen records from core samples show that Cannabaceae plants were present in the Italian peninsula since at least the Late Pleistocene, while the earliest evidence of their use dates back to the Bronze Age. The mass cultivation of industrial cannabis for the production of hemp fiber in Italy really took off during the period of the Maritime Republics and the Age of Sail, and continued well after the Italian Unification, only to experience a sudden decline during the second half of the 20th century, with the introduction of synthetic fibers and the start of the war on drugs, and only recently it is slowly experiencing a resurgence.

Recent developments

The production of cannabis for both medical and industrial purposes has seen a resurgence in Italy in recent years, as a consequence of dedicated EU regulations, and the development of new technologies and innovative applications involving cannabis plants. In fact, said regulations are specifically referenced in the cannabis light Law 242/16 of 2016, of which one of the stated aims is the support and promotion of the hemp sector (Cannabis sativa L.) as a crop capable of reducing environmental impact in agriculture, reducing land consumption and desertifcation and loss of biodiversity, and as a crop to be used as a possible substitute for surplus crops and as a rotational crop. For these purposes, said law introduced looser requirements regarding the cultivation of cannabis plants with levels of THC below 0.2%, which came into force in 2017, and prompted hundreds of new businesses to start growing cannabis in several Regions, with the estimated cultivation area increasing ten-fold, from 400 ha (4.0 km; 1.5 sq mi) in 2013 to almost 4,000 ha (40.0 km; 15.4 sq mi) in 2018.

The national hemp cultivation area involves more than 800 farms, mainly spread between the Regions of Tuscany, Piedmont, Veneto, Sicily, Apulia, Emilia-Romagna, Basilicata, Abruzzo, and Sardinia. The size of the individual hemp farms can vary from small patches of 0.001 ha (10.0 m; 12.0 sq yd) in the mountains, to fields spanning more than 100 ha (1.0 km; 0.4 sq mi) in the plains, particularly in Campania, and almost all of them use the harvested crops to produce more than one type of end-product. The certified seeds used for sowing can come from Italian Hemp Associations and Cooperatives, such as Tecnocanapa, Assocanapa, and Federcanapa; as well as from abroad, particularly Germany, France, and the general area of Northeastern Europe. In regard to possible future expansions, it is estimated that with the potential redevelopment of already-existing greenhouses, which either fell into disuse or were abandoned due to the crisis of the horti-floriculture sector, Italy would have ready access to a further 1,000 ha (10.0 km; 3.9 sq mi) of farm land for the production of medical cannabis within secure environments.

In terms of imports of industrial cannabis, Italy reported in 2017 a total of 8 t of seeds for sowing, 884 t of seeds for other uses, and 0.3 t of fiber, while the reported numbers for 2018 were equal to 46, 557, and 11 t, respectively. Such imports were mainly from Canada, France, the Netherlands, Germany, and China. According to an analysis by the Observatory of Economic Complexity, Italy was the 5th largest importer of hemp fibers in the world in 2020, although the goods were just the 1,104th most imported product of the country. Moreover, the main import markets for Italy were Spain, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Austria, and Switzerland, of which Netherlands, Spain, and Austria were the fastest growing between 2019 and 2020; while the main importing competitors for Italy in 2020 were Spain, Germany, and Switzerland. In terms of exports, Italy was the 4th largest exporter of hemp fibers in the world in 2020, even though the goods were just the 1,033rd most exported product of the country. Furthermore, the main export markets for Italian hemp are Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, Spain, and the United Kingdom, the first three of which were the fastest growing ones between 2019 and 2020; while the main exporting competitors for Italy in 2020 were France, the Netherlands, and the United States.

In regard to publicity programs, the Canapa Mundi International Hemp Expo was established in 2015, based on an idea from its founder and pioneer of the modern Italian hemp market Gennaro Maulucci, and it is officially recognized by the Region of Lazio as an International Fair. In the last few years, the annual event has been held at the Fiera di Roma exhibition center in Rome, with the attendance of as many as 30,000 visitors, as well as several hundreds of both national and international entities, including research institutes, private companies, and universities. Besides providing exposure of the cannabis and hemp sectors to the wider public, the exhibition also aims at supporting the companies that work in these fields, with a list of addressed topics that include biodiversity, sustainability, food, wellness, textiles, constructions, culture, and innovation. Nevertheless, the earliest Italian trade show dedicated to the many facets of the hemp business is the Indica Sativa Trade International Hemp Fair, whose first edition was held in Fermo in 2013. In recent years, the annual event has been held at the Unipol Arena in Bologna, with the attendance of as many as 25,000 visitors, as well as hundreds of exhibitors and business professionals, including representatives from ConfAgricoltura, Cia – Agricoltori Italiani, FederCanapa, Assocanapa, Coldiretti, EasyJoint, and The Bulldog. Although the event has a particular focus on the Italian hemp market, it involves a significant number of European and worldwide producers, with dozens of training courses, conferences, and seminars covering a wide range of topics, including recreational use, constructions, health, pet food, natural food, textiles, energy, and agriculture.

Legalization efforts

In 2012, a study was published regarding the trace presence of psychotropic substances such as cocaine, cannabinoids, nicotine, and caffeine, in the air of eight major Italian cities, namely Palermo, Turin, Rome, Bologna, Florence, Milan, Naples, and Verona. The analysis of a year's worth of atmospheric data revealed what appears to be a seasonal trend in the consumption of cannabinoids, with measurements consistently peaking during winter in all eight locations, while all but disappearing during the warmer period between May and August.

In addition, higher-than-average levels of cannabinoids were measured in both Bologna and Florence, and these were mainly attributed to student culture, considering that the two relatively close historic cities are both major academic hubs that attract a large number of international students every year, especially when compared with their respective small populations, both numbering between 350,000 and 400,000 residents. In fact, according to a 2017 Parliamentary report on drug addiction in Italy, cannabis is the most common psychoactive substance among both the adult and the very young, with about 90,000 Italian students reporting an almost daily cannabis consumption, and almost 150,000 appearing to make problematic use of the drug.

In regard to public opinion, according to a 2015 poll by Ipsos, 83% of Italians deem laws prohibiting soft drugs as ineffective, 73% are in favour of legal cannabis, and 58% think that legalization would benefit public finances. In terms of consumption rates, about a third of the Italian population has experimented with cannabis at least once in their lives, while 25% of people aged 15 to 19 years old reported using cannabis for recreational purposes at least once in 2014, as well as more than 25% of high school students in 2016. Moreover, according to a 2018 report by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Italy ranks 3rd in the European Union in terms of cannabis use, with a lifetime consumption rate of 33.1%, after France at 41.4%, and Denmark at 38.4%. Nevertheless, despite an increased availability of cannabis-derived products with elevated THC levels, only 11% of users seek treatment from public services, while hospital admissions related to cannabis use constitute only 12% of those related to drug use in general.

2016 political debate

The popularity of recreational cannabis led in 2016 to renewed legalization efforts in Parliament, where legislation was proposed with the support of several politicians, mainly from the centre-left Democratic Party, the left-wing Left Ecology Freedom party, the anti-establishment Five Star Movement, the anti-prohibition Radical Party, and even a few from the conservative Forza Italia party, as well as members of the Anti-Mafia Directorate. Proponents of the legislation pointed at the failure of prohibitionism in reducing cannabis consumption and argued that legalizing cannabis would regulate the circulation of cannabis-related products, reduce consumption among adolescents, allow the police and courts to focus their resources on other issues, and deprive criminal organizations of a significant source of revenue by redirecting it toward the State in the form of taxes, similarly to what happened in Colorado after it legalized cannabis in 2012. In particular, the value of the illegal cannabis market in Italy is estimated between 7.2 billion and more than 30 billion euros, while the potential tax revenue from legal cannabis is estimated between 5.5 and 8.5 billion euros. Moreover, the potential GDP boost resulting from a legal cannabis market in Italy is estimated between 1.30% and 2.34%.

Nevertheless, legalization efforts were opposed by several conservative and catholic-leaning politicians, mainly from the Northern League party and the New Centre-Right party, who argued that the consumption of cannabis constitutes a health risk and that legalization will not reduce drug addiction. The PD-led coalition government at the time, which included the New Centre-Right, was mainly focused on ensuring the passage of constititutional reforms, therefore cannabis legalization was not considered a priority. After the defeat of the constitutional referendum and the subsequent resignation of then Prime Minister Matteo Renzi on 12 December 2016, legalization efforts stalled in Parliament.

Cannabis light

In 2016, the cannabis light Law 242/16 removed the need for authorization to plant certified cannabis seeds with levels of THC below 0.2%, which is lower than the 0.3% limit defined by the EU Regulation 2021/2115 of 2 December 2021, while the detection of THC levels between 0.2% and 0.6% during field inspections is still considered acceptable, when it can be attributed to natural causes. The law also requires farmers to keep the certification receipts for up to one year, while also prohibiting them to plants the hemp seeds produced with a previous crop, as well as to use the cannabis leaves and inflorescences for edible products. The State Forestry Department is in charge of checking that farmers are complying with the established legal framework, as indicated by European regulations, although other State entities can carry out inspections if it is deemed necessary.

The potential revenue from the sale of cannabis light in Italy was estimated to be more than 40 million euros, and by 2018 hundreds of new businesses started growing cannabis in several Regions. Even though these looser requirements were originally intended to benefit farmers growing industrial hemp, with the production being limited to the 75 varieties of industrial hemp registered in the EU Common Catalogue of Varieties of Agricultural Plant Species as per the EU Council Directive 2002/53/EC of 13 June 2002, a lack of clarity regarding the use of cannabis inflorescences effectively created a booming unregulated market for recreational light cannabis. In particular, approximately 2,000 light cannabis shops, delivery services, and vending machines have sprung up in Italy, selling hemp inflorescences and leaves as collector's item. In fact, since the law does not explicitly prohibit the sale of hemp flowers, customers can legally buy them, and then they can simply crumble them, roll them, and smoke them. The aforementioned 0.2% limit for the allowed THC content is considerably lower than the 15–25% range typically found in marijuana, thus preventing cannabis light users from actually getting stoned, however proponents of cannabis legalization are confident that the spread of cannabis light can contribute to the normalization of cannabis overall. According to 2018 estimates by the National Consortium for Hemp, the then almost 1,000 brick-and-mortar stores, in addition to several other specialized online shops, were part of an emerging hemp sector that employed as much as 10,000 people, with an average age of 35 years, generating an annual revenue equal to 150 million euros.

Nevertheless, in September 2018, then Interior Minister and Northern League party leader Matteo Salvini issued a memo to law enforcement agencies outlining a zero-tolerance policy towards cannabis retailers. In particular, the directive stated that cannabis products that contain THC levels above 0.2%, or that are made from plants not included in the official list of industrial hemp varieties, must be considered as narcotics and thus confiscated. Moreover, the Superior Council of Health, which provides technical-scientific counsel to the Ministry of Health, recommended in April 2018 to stop the free sale of cannabis light, as a public health precaution. The Council argued that the industrial applications of cannabis, as envisaged in the Law 242/16, do not include cannabis inflorescences; and they also cited a lack of scientific studies on the effects of even small levels of THC on possibly vulnerable subjects such as older people, breastfeeding mothers, and patients with certain pathologies, which prevents them form ruling out possible health risks. Adding to the uncertainty in the cannabis light market, the Supreme Court of Cassation ruled in May 2019 that the sale of derivatives of cannabis sativa which do not fall within the scope of the Law 242/16, most notably oils, resins, buds, and leaves, is illegal under Italian Law unless such products are effectively devoid of narcotic effects. The Court also reaffirmed that only certain agricultural varieties of cannabis are permitted under the Law 242/16, which was meant to benefit farmers growing industrial hemp.

In 2019, a team of economists from the University of Magna Graecia, Université Catholique de Louvain, and the Erasmus School of Economics published a study on the effect of light cannabis liberalization in Italy on the organized crime. Albeit light cannabis does not generate hype as illegal marijuana, the study showed that confiscations of illegal marijuana declined with the opening of light cannabis shops. The authors also found a reduction in the number of confiscations of hashish and plants of marijuana along with a reduction of arrests for drug-related offenses. Forgone revenues for criminal organizations were estimated to be at least 90–170 million euros per year. Conversely, the total revenue from the cannabis light market was estimated to be more than 200 million euros in 2020.

On 14 February 2023, the Regional Administrative Court of Lazio annulled a Ministerial Decree that was promulgated on 21 January 2022, which limited the purposes of industrial cannabis production to the exclusive use of the seeds and seeds derivatives. In particular, the aim of the Decree was to place the cultivation, processing, and marketing of non-narcotic hemp leaves and inflorescences under the purview of the Ministry of Health, which would have been responsible for issuing the necessary authorizations for such activities, as if they involved narcotics. As a result of the Court's ruling, the use of the whole hemp plant is authorized in Italy, including leaves and inflorescences, thus bringing the country in line with EU regulations.

International treaties

On 2 December 2020, under the recommendation of the World Health Organization (WHO), the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) voted to remove both cannabis and cannabis resin from the Schedule IV classification of the aforementioned 1961 UN Convention, while still including them both in the less strict Schedule I category. In its capacity as a serving member of the CND, and in agreement with other members of the EU, with the exception of Hungary, Italy voted in favor of the rescheduling proposal, since it would allow more research, in line with our evidence-based drugs policy, on the medical use of cannabis and cannabis resin.

Among the other recommendations of the WHO, there was the proposed addition of a footnote to the Schedule I section of the Convention, stating that preparations containing predominantly cannabidiol and not more than 0.2 per cent of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol are not under international control. However, the proposal was ultimately rejected by a majority of member states for several reasons, including the argument that no action is needed on CBD since it is not currently under international control. In this case, Italy voted against the recommended footnote, citing as reasons the lack of scientific evidence on the proposed 0.2% limit, ambiguous wordings within the draft that could lead to divergent interpretations, and the absence of justification for the proposed different treatment of cannabidiol compared to other non-psychoactive cannabinoids.

Personal use

In July 2008, the Supreme Court of Cassation ruled that followers of the Rastafari religion can smoke marijuana as a meditative herb after a man from Perugia, who was initially sentenced in 2004 to 16 months in jail and a €4,000 (4,900 US$) fine for possession of 97 g of marijuana, was acquitted on religious grounds. In December 2019, the Court ruled that cultivating domestically small amounts of cannabis for the exclusive use of the grower is legal under Italian Law, after being asked to clarify previous conflicting interpretations of the law. The ruling did not specify what constitutes a legally allowed small amount of cannabis, however the defendant involved was initially sentenced by a lower court to one year in prison and a €3,000 (3,900 US$) fine for the possession of two plants.

The Court argued that public health is not threatened by a single cannabis user cultivating a few plants in a domestic setting and, to justify the assessment of a personal use of the plants, it pointed out the small size of the cultivation. In particular, the Court argued that, given the rudimental techniques used, the small number of plants present, the modest achievable amount of the final product, and the lack of evidence connecting it to a larger narcotic market, the cultivation appeared to be destined exclusively for the personal use of the defendant, and should therefore be considered excluded from the application of the penal code. The ruling came just days after a proposed amendment to the 2020 budget calling for legalisation and regulation of domestic cannabis use, although already approved by the Lower House, was ruled inadmissible by the President of the Senate on technical grounds.

In April 2021, a patient with acute rheumatoid arthritis was acquitted of drug pushing after a court ruled that he was allowed to exceed the legal limits of cannabis cultivation, after running out of an adequate supply of medical cannabis due to the COVID-19 pandemic, on the grounds that it was for his personal health use. In September 2022, another patient with fibromyalgia, for which a daily dose of one gram of medical cannabis is usually prescribed, was acquitted of the same charge of drug trafficking, for which he had been arrested in June 2019 after two cannabis plants were found in his house, together with rudimental tools for cultivating, preserving, and weighing cannabis, as well as a stock of the final product sufficient for just above a month of therapy, with a THC content ranging between 0.32% and 2.38%. The patient lives in Calabria, which has not yet approved for medical cannabis to be covered by its Regional Health Agency, similarly to Molise and Aosta Valley, thus leading to higher costs and a distribution limited to a few pharmacies. Critics have also argued that such serious charges would lead patients to buy cannabis directly from illegal pushers instead of growing it themselves, since they would risk just a fine, confiscation of documents, and a mandatory rehabilitation program for possession, as opposed to 6 years in prison for drug pushing. In particular, a third of all the illegal marijuana produced in Italy is reportedly cultivated in Calabria, due to its favorable climate, with the 'Ndrangheta being the leading criminal organization for drug trafficking in both Italy and Europe.

In September 2021, a preliminary text was approved by the Justice Committee in the Lower House that would decriminalize the small-scale cultivation of up to four female cannabis plants at home for exclusively personal use. The stated aim of the proposed legislation is to make sure that patients have access to medical cannabis, as well as to combat criminal organizations involved in drug trafficking. The law would also lower the penalties for minor cannabis-related infractions from 2–6 years in prison to 1 year at most, thus distinguishing it from hard drugs like heroin, while it would increase penalties related to drug trafficking to 6–10 years.

2021 decriminalization initiative

At the same time, a ballot initiative was launched that aimed at the decriminalization of the cultivation of marijuana, as well as the repeal of penalties for cannabis possession, by amending the relevant laws through a referendum. According to Article 75 of the Constitution, general referendums are allowed for repealing a law or part of it, when they are requested by either 500 thousand voters or five Regional Councils, while neither propositional referendums nor referendums on a law regulating taxes, the budget, amnesty or pardon, or a law ratifying an international treaty are recognised. Therefore, the legislative process regarding the legalization of recreational cannabis can only go through Parliament. Instead, the objective of the campaign was to amend several articles of the Presidential Decree DPR 309/90 of 1990, regarding the discipline of narcotics and psychotropic substances, prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation of the related stages of substance dependence, which is reportedly responsible for 35% of the current prison population in Italy. The initiative was supported by several pro-legalization organizations, including ARCI and the Luca Coscioni Association, as well as several political parties, including Italian Radicals, +Europa, Possible, Power to the People, Communist Refoundation, and Italian Left.

In its first week of operation, the campaign collected 400 thousand signatures in less than four days and reached the required 500 thousand signatures well before the deadline set at the end of September, which would have allowed the referendum to take place as early as spring 2022. The speed at which the signatures were collected was made possible by a law approved in July 2021 that allows for signatures to be collected online, while previously only in-person signing was allowed, and the campaigners continued to collect signatures up until the deadline, to make sure that the initiative would not be rejected due to some of them being ruled invalid. In fact, the campaign managed to collect as much as 630 thousand electronic signatures in a single week, 70% of which were from people under 35 years old.

As prescribed by the law, the collected signatures were verified by the Supreme Court of Cassation on 12 January 2022, however the Constitutional Court ruled on 16 February 2022 that the ballot question was inadmissible, thus preventing the referendum from going forward. The Court argued that the proposed changes to the legislation would not have affected just the cultivation of marijuana, but also of plants like poppy and coca, from which opioids and cocaine can be derived. These potential changes to legislation regarding hard drugs would have violated international obligations, and therefore were ruled not in line with the constitutional provisions on referendums in Italy.

Cost–benefit analysis

High Mid Low Absent

According to a cost–benefit analysis carried out by researchers from the Sapienza University of Rome and the Erasmus School of Economics, cannabis legalization would have an overall beneficial effect in terms of both public finances and healthcare, with two possible legalization models that would lead to completely different fiscal realities. In the State monopoly model, cannabis-based products would be sold in tobacco shops with a taxation at around 80%, similarly to cigarettes, resulting in a tax revenue estimated between 3 and 4 billion euros, potentially reaching 5 billion euros if all habitual cannabis consumers were to buy it instead of growing it themselves. In addition, this model would create 60,000 seasonal jobs, mostly involved in the post-harvest manufacturing stage.

The less-likely alternative is the Dutch model, in which production and distribution would not be under the purview of the State, although the drug would still be taxed. As a consequence, the cultivation, marketing, and sale of the final products would be left to the private sector, resulting in the establishment of tens of thousands of coffeeshops to satisfy the local demand, and creating about 300,000 jobs. The unlikelihood of this model is mainly attributed to an assumed conservative mindset which, at least initially, would seek to make cannabis legalization as least visible as possible, despite the reduced fiscal benefits.

Another significant benefit is the removal of the costs of prohibitionism, which include missed tax revenues, prosecution expenses, policing costs, and prison overcrowding, for an estimated total of 500 million euros each year, that could instead be refocused on more serious offences and more dangerous substances. In regard to the organized crime, which currently has a monopoly on an illegal cannabis market conservatively estimated to be worth between 4 and 5 billion euros, it is believed that legalization would not cause the black market to suddenly disappear. Conversely, at least in the short term, the State would compete with criminal organizations benefiting from a 30 to 40 years experience in full control of the sector, that could still find a minority of customers willing to buy cheaper illegal products. In the long term, a significant problem would be the potential infiltration of organized crime into the different sections of the newly legalized cannabis market, especially with the possible establishment of front organizations for the purpose of money laundering.

In terms of public health, the legalization of cannabis would allow for more scientific research; it would disincentivize the use of potentially hazardous, low-quality, illegal products, for which the cannabis is often processed with harmful substances to reduce costs and increase profit margins; and it would cause a split in the black market for narcotics by distancing cannabis users from illegal pushers, who are economically incentivized to sell more dangerous drugs, such as heroin and cocaine, in addition to cannabis.

2022 general election campaign

Paper ballots being cast for the Italian Senate and Chamber of Deputies, respectively, during the 2022 general election.

Paper ballots being cast for the Italian Senate and Chamber of Deputies, respectively, during the 2022 general election.

Following the removal of the cannabis decriminalization proposal from the referendum of 12 June 2022, the issue resurfaced during the campaign for the snap general election that was held on 25 September 2022, after the resignation of the then Prime Minister Mario Draghi on 21 July 2022. In terms of public opinion, Italy is the country with the highest support in Europe for legal, government-regulated sales of cannabis products to customers over the age of 18, with an estimated 60% of the people being in favor of it, 22% being against it, and 16% neither supporting nor opposing the policy, according to a 2022 report published by the consultancy agency Hanway Associates, in collaboration with Curaleaf International, the Cansativa Group, and the international commercial law firm Ince.

During the campaign period, an analysis of the different political platforms divided the various parties between those that were explicitly in favor of legalization and regulation of recreational cannabis, which included Possible, the Democratic Party, the Five Star Movement, the People's Union, the Greens and Left Alliance, and +Europa; those that did not touch the subject, which included Action – Italia Viva, Brothers of Italy, Forza Italia, and Italexit; and the only one that was publicly and unambiguously against it, namely the League.

Even though the Brothers of Italy party, led by the subsequently-elected Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, did not explicitly mention cannabis legalization during their campaign, other than labeling the drug as one of the youthful deviances that need to be tackled with the promotion of healthy lifestyles, their leader had discussed the subject multiple times in the past. In particular, she discussed the lethality of drugs in general; the need for actions to contrast their spread; and her dismissal of the idea of drug legalization as a means to fight the Mafia, citing the similar position held by the late anti-mafia magistrate Paolo Borsellino. Similarly, the League party led by Matteo Salvini, which went on to form the resulting coalition government together with both Brothers of Italy and Forza Italia, campaigned on the position of stopping any decriminalization or legalization proposal; dismissing any distinction between hard and soft drugs, echoed in the often-used slogan Drug is Death; and launching sensibilization campaigns aimed at minors and their parents, regarding the dangers of the drug culture, and in particular the effects of the habitual use of cannabis on the cognitive development of the youths.

In contrast, the most fervently pro-legalization platform, published by Possible, pointed at the case study of Portugal which, according to a 2017 report by the IZA Institute of Labor Economics, experienced a decrease in both the number of drug-related deaths, and the number of new patients entering drug rehabilitation, following its decriminalizion of all drugs in 2001. Similarly, the other proponents reiterated the need to legalize cannabis cultivation for personal use in the context of both fighting organized crime, and ensuring that medical cannabis is available to patients in need, as well as a matter of individual liberties. Other proposals also include the launching of information and prevention campaigns for schools, as well as the wider public, to increase the public awareness regarding the risks of any form of substance abuse and dependence.

In regard to the private sector, the non-partisan Confederation of Italian Farmers (CIF) association published a 10-points document addressed to all political parties, lobbying for clear regulations regarding cannabis, among other things, as a means to support plant growers in the context of the 2021–2023 global energy crisis and inflation surge. In particular, Italy ranks 3rd in the European Union in terms of the production of plants and flowers, with the internal market worth an estimated 3 billion euros in revenues, creating more than 100,000 jobs spread among 24,000 businesses; and the main challenge faced by the sector was reported to be a 74% increase in the production costs, combined with the general inflation and the loss of purchasing power by the consumers, which resulted in reductions in sales of as much as 30%. In the published document, cannabis is recognized as a plant with enormous potentials in every field, that still suffers from unclear regulations; and for this reasons the CIF requested the future government to allow credit access for hemp-producing businesses, the liberalization of the sale of CBD, the agamic reproduction of hemp plants, investments into new varieties for different uses, the processing of all parts of the plant, the definition of a THC level below which all parts of the plant are marketable, and the reorganization of the means of production for cannabis-based pharmaceuticals.

Law enforcement

Cannabis inflorescences are classified as narcotics and their pharmaceutical use is strictly regulated in accordance with the aforementioned UN Conventions of 1961 and 1971, EU regulations, as well as national legislation, including the aforementioned DPR 309/90 of 1990. The cultivation of cannabis plants for pharmaceutical use, as well as the production and distribution of cannabis-based medicine, are allowed only for authorized entities, while the DPR 309/90 forbids both the direct and indirect advertisement of a list of derived substances. Nevertheless, farmers can cultivate cannabis for exclusively non-pharmaceutical purposes, such as the production of fibers or other industrial applications, using certified seeds under the direction of the Ministry of Agricultural, Food, and Forestry Policies (MAF).

Central Office for Narcotics

In November 2015, Italy instituted the Central Office for Narcotics, in accordance with the 1961 UN Convention and subsequent amendments, which instruct countries allowing the cultivation of cannabis for medical purposes to create a state agency for its management. The functions of the Central Office for Narcotics include:

- implementing national and EU regulations regarding narcotics and psychoactive drugs;

- updating the official list of narcotics and psychoactive substances;

- authorizing the cultivation of cannabis for the production of medicine and other substances;

- approving areas dedicated to the cultivation of cannabis;

- approving the exportation, importation, distribution within the national territory, and storage of cannabis plants and derived materials, with the exception of stocks kept in facilities authorized for the production of medicine;

- determining the production quotas based on Regional requests, and relaying that information to the International Narcotics Control Board.

Central Directorate for Anti-Drug Services

The Central Directorate for Anti-Drug Services (CDA) is a joint organization involving the State Police, the Carabinieri, and the Financial Guard as well as civil administration personnel from the Ministry of the Interior in the fight against drug trafficking. The three law enforcement agencies are equally represented in the Directorate, with the director-general being selected every three years from the three agencies on a rotational basis. The Directorate was originally instituted as the Anti-Drug Directorate through the Law 685/75 of 1975, and underwent several changes over the years, becoming the Central Anti-Drug Services through the Law 121/81 of 1981, until the Law 16/91 of 1991 defined its current structure and functions. The Directorate is made of three main branches, each containing two Divisions.

The General and International Affairs (GIA) branch carries out multilateral, training, and legislative initiatives and also provides technical support to the Criminal Police. International initiatives are coordinated with the United Nations and the European Union as well as other agencies including the G7 Rome-Lyon Group, the Maritime Analysis and Operations Centre, Ameripol, the Paris Pact Initiative, and the International Drug Enforcement Conference. The GIA branch manages training and educational activities at both a national and international level through courses, conferences, and workshops; and it also gives technical-juridical advice with regards to bills and regulations on narcotics and drug trafficking.

The Studies, Research, and Information (SRI) branch conducts research and intelligence activities, in particular monitoring national and international drug trafficking. The analysis includes local consumption statistics, trafficking routes, production and market areas, concealment methods, demographics of the people involved, and evolution of new narcotics. At the international level, the SRI branch collaborates with the International Narcotics Control Board. It also gathers and processes information from both national and foreign sources regarding drug-related confiscations, arrests, and deaths, subsequently relaying these data to the National Statistics System (SISTAN), as well as using them for internal reports. Finally, the SRI branch offers support upon request in terms of providing bibliographical references for academic and research purposes.

The Anti-Drug Operations (ADO) branch coordinates police activities against drug trafficking through intelligence and strategic, operational, and technical-logistical support both at a national and international level. The ADO branch also approves and coordinates undercover operations, manages naval boarding requests against suspicious vessels in international waters, and monitors internet activities related to drug trafficking.

Illegal drug trade

The main narcotic substances obtained from the female inflorescences and resin of cannabis plants are marijuana, hashish, and hashish oil. According to the CDA, the major marijuana producers worldwide are Albania, supplying Italy and parts of Europe; Mexico and the United States, mainly supplying North America; and Paraguay, which represents the main distribution center for all of South America; while Morocco represents the main producer of hashish. Moreover, the three main routes for the illegal trade of cannabis-derived substances are from Mexico towards the United States and Canada; from North Africa, through Spain, towards the European markets; and from Albania, through the Adriatic Sea, towards Italy and other European markets. Furthermore, the Italian black market for marijuana is also supplied by the Netherlands, as well as local producers.

According to data from the Italian National Institute of Statistics, the number of consumers of illegal cannabis is estimated to be equal to 6 million people, which includes the estimated 500,000 daily consumers as well as the more occasional users, with habitual consumers representing 90% of the market. The overall economic activities resulting from the black market for narcotics in Italy are valued at 16.2 billion euros, of which about 39% can be attributed to the consumption of cannabis derivatives, and almost 32% to cocaine use, as inferred from a Parliamentary report on drug addiction. In fact, cannabis is the most frequently confiscated narcotic in Italy as a result of the consistently high demand, for a total of 67.7 t (66.6 long tons) in 2021, which by itself represents more than two-thirds of the 91 t (89.6 long tons) of drugs confiscated overall by law enforcement officials in the same year. In addition, as much as 20.9 t (20.6 long tons) of the entire illegal cannabis haul consisted in inflorences and derivative products with low THC levels. Furthermore, both consumption rates and prices have reportedly remained the same in the previous ten years, with the only significant change being the exponential increase in personal cannabis cultivations, mainly due to the particularly favorable Italian climate.

Medical cannabis

Since 1998, doctors in Italy have been able to prescribe cannabis products and synthetic cannabinoids for therapeutic use, with a non-repeatable prescription, while the therapeutic uses of THC, dronabinol, and nabilone are recognized since 2007. After the inclusion of the active compounds of cannabis plant origin in the Medical Table by Ministerial Decree on 23 January 2013, doctors in Italy are able to prescribe cannabis-based medicine and any pharmacy, if properly supplied, can distribute cannabis products in the forms and doses defined in the doctor's prescription. Medical cannabis can be used for treating several conditions, and its prescription is allowed when the patient is unresponsive to conventional or standard therapies, while the list of medical applications includes:

- relieving both oncological and neuropathic chronic pain, including pain associated with cancer, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injuries, and diabetic neuropathy;

- treating nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and HIV treatments;

- stimulating appetite for patients with cachexia, anorexia, cancer, and AIDS;

- inducing hypotension within glaucomas;

- managing neurological diseases, such as spasticity caused by multiple sclerosis, levodopa-related dyskinesia caused by Parkinson's disease, extra-choreic disturbances caused by Huntington's disease, involuntary movements caused by Tourette syndrome, as well as some forms of epilepsy.

There are three methods to administer cannabis-based medicine, namely infusions that can be normally sipped, oil extracts that can be spread on bread, and decoctions, the latter being less common since their packaging is more complicated. The reported list of possible side effects derived from the consumption of medical cannabis include tachycardia, hypotension, paranoia, dizziness, reduction in the cognitive development and psychomotor performance, alteration of attention and memory, psychiatric disorders, damage to the airways and lungs, risk of addiction, and weight reduction in newborn babies if used during pregnancy.

The cost of medical cannabis is completely covered by the Healthcare system for six medical conditions, while for others it can be purchased from pharmacies at a greatly reduced price. Furthermore, in June 2017, the Ministry of Health established a maximum price for medical cannabis between €8.50 (9.1 US$) and €9.00 (9.7 US$) per gram, to standardize the expenses sustained by patients. However, this price cap has resulted in a short supply of the product due to limited profit margins for pharmacies, while regional legislative differences also add to the overall complexity of the cannabis market. For example, the Regions have the ability to decide for which health conditions the drug can or cannot be prescribed, and they can also increase local prices to make it profitable for pharmacies to sell medical cannabis (e.g. Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol), or alternatively they can completely cover the cost for patients through their Regional Health Agencies (e.g. Sicily). As a comparison, the cost of medical cannabis imported from the Netherlands is reported between €5 (5.3 US$) and €10 (10.7 US$) per gram.

In October 2019, the first public clinic specifically dedicated to the prescription of medical cannabis was established in Naples by the University of Campania, to facilitate access to it by patients, who previously had to rely on either a private clinic at a cost, or a specialist familiar with cannabis-based drugs. In August 2023, the first technological research center for the medical use of cannabis and cannabinoids was established in Apulia, following the allocation of €800,000 by the Regional Council. The aim of the project is to support local pharmacies and hospitals with the titration and characterization of cannabis-based preparations; offer training courses on cannabis-based galenic formulation; and shore up local pharmaceutical industries and start-ups.

State-produced medical cannabis

At the time of the legalization of medical cannabis, the cost of the medicine wasn't covered by the State and the drug had to be imported from abroad through the Office of Medicinal Cannabis, primarily from the Netherlands, making it too expensive for the average patient to buy legally at pharmacies, with prices reaching up to €50 (59 US$) per gram, as well as waiting times reaching up to a month. For this reason, then Defence Minister Roberta Pinotti announced in September 2014 that the Army would begin growing cannabis plants in a secure room at the Chemical-Pharmaceutical Military Institute in Florence, which is already tasked with the production of orphan drugs both as an application of the constitutional right to health care and as a matter of national security. The military facility manages all stages of the production of medical cannabis, including growing and harvesting the plants, drying and grinding the leaves, sanitizing the final product with gamma rays, and then shipping it to pharmacies and hospitals, all in accordance with the Good Agricultural and Collecting Practices and the Good Manufacturing Practices of the EU.

The army production of medical cannabis increased from 20 kg (44.1 lb) between 2014 and 2016 to more than 100 kg (220.5 lb) in 2017, resulting in a 30% decrease in the cost of the final product. Moreover, the Army expanded its cultivation with new greenhouses in other areas of the military facility, to reach an estimated production of 300 kg (661.4 lb) per year and to keep up with the demand from doctors and patients, which was estimated between 400 kg (881.8 lb) and 450 kg (992.1 lb) a year in 2017. In November 2019, the Ministry of Health increased the maximum amount of cannabis inflorescences allowed to be produced by the facility from 350 kg (771.6 lb) to 500 kg (1,102.3 lb) per year, while the Army is planning to reach an annual medical cannabis production of 700 kg (1,543.2 lb) in 2023, by perfecting technical aspects such as lighting, watering, temperature, and ventilation; and by using a mixture of secret nutrients developed in-house that are mixed in with the hydroponic irrigation. The increased production was also achieved thanks to the increase in the number of growrooms, from just two in 2016 to the current ten, as well as the six annual harvests carried out in each one of the six flowering rooms, which individually contain between 50 and 125 cannabis plants.

The state-run production and distribution of medical cannabis is the result of a collaboration between the Ministries of Health and Defence, as well as other entities including the MAF; the Regions; the Italian Medicines Agency; the Superior Institute of Health; and qualified experts. The operation is overseen by the Defence Industries Agency, which is the arm of the Ministry of Defence that handles the commercialization of the State's defense enterprises, while its aim is to ensure the availability of the raw material; guarantee the safe preparation and use of cannabis-based medicine; prevent the use of unauthorized, illegal, or counterfeit products; and make therapies affordable by reducing the cost of cannabis. In particular, the final price of the product being sold to pharmacies by the military facility, which is just based on the estimated production costs, is equal to €6.88 (7.39 US$) per gram, not including the VAT. The military facility currently produces two registered types of cannabis-based ingredients, which are then distributed to pharmacies in a minced form to be used in their formulations.

The first product is Cannabis FM2 (a.k.a. Farmaceutico Militare 2, i.e. Military Pharmaceutical 2), which is similar to the Bediol strain; consists of unfertilized, dried, and milled female inflorescences; and has been available to the Regions since 14 December 2016. The THC content of Cannabis FM2 (i.e. between 5% and 8%) is lower than the levels commonly found in similar drugs sold in the black market, or even in those legally imported from the Netherlands, while its CBD content (i.e. between 7.5% and 12%) is comparatively higher due to its more useful anti-inflammatory properties. There are also minimal contents of cannabigerol, cannabichromene, and tetrahydrocannabivarin, for a total percentage of less than 1%. Since July 2018, Cannabis FM1, which is similar to the Bedrocan variety, has also been available to the Regions, and it shows a considerably higher THC content (i.e. between 13% and 20%), as well as a considerably lower CBD content (i.e. less than 1%). The higher THC content makes Cannabis FM1 more suitable to mitigate the symptoms of conditions like multiple sclerosis. In 2023, the facility is also aiming to produce cannabis-infused olive oil, which patients can take in drop forms.

Chemical-Pharmaceutical Military Institute

The origins of the Chemical-Pharmaceutical Military Institute in Florence date back to 1853 in the Kingdom of Sardinia, when the General Chemical-Pharmaceutical Laboratory was established in Turin by royal decree, as part of the Military Pharmacy Warehouse, to provide the military with the medical supplies and medications needed, as well as combating diseases like malaria, which was widespread in Italy at the time. After the Great War, plans were made to modernize the Laboratory, and move it to a more central location within the Italian peninsula, to improve the distribution of supplies. The current facility, covering about 55,000 m, was thus constructed in Florence, becoming operational in October 1931, and producing several types of medicine, medical supplies, cosmetics, and food products, with a workforce peaking at 2,000 people in the 1940s.

Renamed the Chemical-Pharmaceutical Military Institute in 1976, beside the production of medical cannabis, the institute also produces five different orphan drugs, as well as maintaining the national stockpile of antidotes in case of mass poisoning, terrorist attacks, and nuclear disasters, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health which manages a net of warehouses located in each Region. In particular, the facility was involved in relief efforts during several natural and man-made disasters, including the Florence flood of 1966, the Friuli earthquake of 1976, the Irpinia earthquake of 1980, as well as the Chernobyl nuclear disaster of 1986, for which the institute produced 500 thousand pills of potassium iodide in less than 24 hours, to combat the thyroid damage caused by Iodine-131. The facility has also been involved in the production of medicine and medical supplies for international assistance, such as during the Romanian revolution of December 1989. More recently, the Army's activities facilitated a steady increase of its involvement in the public health sector, that further accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, for which military personnel was charged to set up treatment tents and transport vaccines.

The military facility is a non-profit institute, operating on a balanced budget since 2008 and reinvesting any surplus into research and production, and collaborating with several Italian universities in several fields of research and education. To avoid unfair competition with the private sector, the facility mainly focuses on the research and production of unprofitable drugs used to cure rare diseases, which are defined as affecting just one every 2,000 people. In particular, the army-produced orphan drugs currently supply just 3,000 people in all of Italy, although possible revenue may still be obtained from exporting such drugs, with potential customers numbering at least 400 million people worldwide. With regards to the production of medical cannabis, the facility is looking for a public–private partnership to increase the overall production, possibly reaching 4,000 kg (8,818 lb) a year, thus covering the national demand while also providing export opportunities. Currently, five private firms are set to supply the facility with more mother plants, from which cuttings can be taken to produce more plants; however, there are still no plans to outsource the main operation to the private sector.

Private sector

The potential revenue from medicinal cannabis is estimated to be more than 1.4 billion euros, with the internal market creating at least 10,000 jobs and reducing the dependence on imports. In September 2021, the Ministry of Health clarified that industrial hemp can be cultivated for the purpose of supplying pharmaceutical companies authorized to manufacture active pharmaceutical ingredients, on the conditions that the growers obtain the required authorizations and use exclusively EU certified seeds. In addition, licensed private companies can also import cannabis-based medicine from abroad; for instance, the Italian pharmaceutical distribution company FL Group, a division of the American Tilray Medical, received authorization in 2023 to import and distribute three new compounds, with the aim of reaching more than 12,000 pharmacies through dedicated marketing and information campaigns on the benefits of medical cannabis.

In February 2021, Bio Hemp Farming, which is a consortium between the Bio Hemp Trade company and the Palma d'Oro cooperative, became the first private entity in Italy to be granted authorization by the Ministry of Health to grow medical cannabis and to extract its active principles for pharmaceutical purposes. The consortium currently manages two different sites for growing medical cannabis, with a total cultivation area of 300 ha (3.0 km; 1.2 sq mi), in Cerignola, Apulia. The leaves and inflorescences harvested from these sites are sent to two pharmaceutical laboratories for the extraction of cannabidiol for medical purposes, while the stems and fiber are instead used for industrial purposes, such as the production of paper, yarns, or biomaterial for construction. An innovative method implemented by the consortium, for the extraction of active principles from medical cannabis, is a cryogenic process in which the low temperatures allow to reduce the preparation time for the final product from 2 or 3 days to about 15 minutes.

Another noteworthy application of cannabis-based medications is in dermatology; for instance, a novel cosmetic line by the Swiss lifescience company Crystal Hemp combines CBD with resveratrol, azelo-glycine, and lactobionic acid, to regulate the production of sebum in sebaceous glands, reduce redness of the skin, and inducing exfoliation. As a result, the combined effect of these substances can help prevent acne, assist in the replacement of dead cells, and alleviate the worst symptoms of skin conditions like seborrhoeic dermatitis. In particular, dedicated studies show that CBD is able to inhibit the lipogenic action of several substances that can be found in cell tissues, reduce the proliferation of sebocytes, and have an anti-inflammatory effect on cells affected by acne.

Consumption statistics

The Ministry of Health also publishes consumption statistics for medical cannabis both at a national and a regional level, based on regional distribution requests and the authorized sale of the product, and the military facility determines its production quotas by taking into account the consumption data from the previous two years, as well as the yearly increases. The annual legal consumption of medical cannabis has grown from 40 kg (88.2 lb) in 2013 to nearly 10 times that in 2017, and the demand is expected to further quadruple as the value of cannabis is more widely understood by doctors. The high demand caused pharmacies throughout Italy to run out of medical cannabis by September 2017, prompting many patients with prescriptions to turn to the black market, while in January 2018 the importation of cannabis was extended to Canada. Currently, imports of medical cannabis from the Netherlands, Canada, Denmark, and Germany are used to compensate for the deficit in the internal production.

As of March 2021, it is estimated that more than 2 million patients in Italy could benefit from medical cannabis, while the total needs are estimated to be at least 2,900 kg (6,393 lb) per year, according to the Estimated World Requirements of Narcotic Drugs 2021 report by the International Narcotics Control Board. However, only about 20,000 patients have access to cannabis-based drugs, according to unofficial estimates, while the COVID-19 pandemic has affected both the importation and the distribution of the medicine. In regard to international travel, a decree issued by the Ministry of Health on 16 November 2007 details all the rules and procedures that should be followed, to allow the carrying of small quantities of medical preparations containing narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances for personal use. In particular, whether they are leaving or entering Italy, travellers carrying small quantities of medical preparations that contain internationally controlled substances are required to hold certain documents, such as a valid medical prescription, attesting that such preparations were lawfully obtained in the country of departure.

| Year | Total sales from pharmaceutical wholesalers | Imports authorized by the Ministry of Health for the Local Health Agencies | Total sales from the military facility to pharmacies | Military production quotas | Total sales of cannabis extracts | Total sales |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 33.315 | 25.275 | – | – | – | 58.59 |

| 2015 | 61.9 | 56.725 | – | – | – | 118.625 |

| 2016 | 127.305 | 102.41 | – | – | – | 229.715 |

| 2017 | 162.475 | 129.265 | 59.745 | 150 | – | 351.485 |

| 2018 | 284.29 | 147.265 | 146.905 | 250 | – | 578.46 |

| 2019 | 451.025 | 252.485 | 157.165 | 350 | – | 860.675 |

| 2020 | 664.94 | 215.255 | 242.6 | 500 | – | 1,122.795 |

| 2021 | 742.5 | 251.46 | 277.515 | 500 | – | 1,271.475 |

| 2022 | 997.87 | 327.42 | 235.39 | 400 | – | 1,560.68 |

| 2023 | 1,085.435 | 178.895 | 162.02 | 400 | 26.84759 | 1,453.19759 |

Industrial cannabis

In 2016, Italy removed the need for authorization to grow certified hemp with levels of THC below 0.2%, while also providing tax incentives and including a research and development funding up to €700,000 (826,000 US$) per year from the MAF. Moreover, a Common Agricultural Policy payment ranging between €250 (285 US$) and €400 (457 US$) per hectare can be granted to Italian hemp growers, and this does not include further possible local funding independently allocated by the various Regions and comuni. On 24 December 2021, through Ministerial Decree, the MAF allocated 3 million euros (3.2 million US$) to the national hemp sector, which included support payments to local hemp growers amounting to €300 ($319) per hectare, up to maximum of 50 ha (0.5 km; 123.6 acres).

In regard to research and development, as opposed to farmers, the previously mentioned Law 242/16 allows public research institutes to reproduce for a year the certified hemp seeds that were purchased in the previous year. In particular, the replanted seeds can be used to grow small amounts of hemp for either demonstrative, experimental, or cultural purposes, which are nevertheless subject to communication to the MAF. Furthermore, the legislation also encourages educational activities, such as training for those who operate in the supply chain for industrial cannabis, to illustrate the properties of hemp plants, as well as their use in the agronomic, agroindustrial, nutraceutical, bio-building, biocomponent, and packaging fields.

In fact, the aim of the Law 242/16 is to stimulate the production of industrial hemp in the country, as well as to offer an alternative to the cultivation of wheat for farmers damaged by low prices, desiccated lands, and competition from large corporations importing grain from abroad. In particular, the potential profit from the cultivation of hemp in Italy is estimated between €600 (700 US$) and more than €2,500 (2,900 US$) per hectare, while the estimated yield for durum wheat is equal to €300 (350 US$) per hectare. Moreover, as a consequence of the increasing number of farmers turning to hemp cultivations, the overall production of durum wheat in Italy decreased by more than 4% in 2017. Nevertheless, producers of hemp fiber in Italy still face significant competition from the low-price fiber produced in China, as well as other Asian countries. This competition is reportedly contributing to the prevalence in Italy of cannabis cultivations aimed at the production of inflorescences, as opposed to fiber, since the wholesale of flowers from cannabis sativa can result in a profit between €300 (350 US$) and €1,500 (1800 US$) per kilogram, depending on the quality, and 1 ha (0.01 km; 2.47 acres) can yield as much as 1,000 kg (2,205 lb) of inflorescences.

Private sector

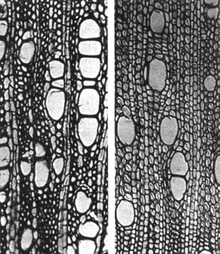

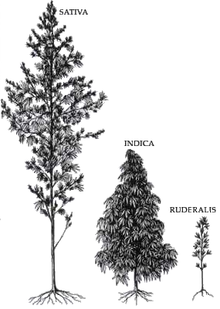

The cultivation of industrial hemp with minimal levels of psychoactive compounds has several commercial applications, including food, fabrics, clothing, biofuel, building materials, as well as animal feed and bedding. Out of the more than 70 hemp varieties listed in the EU register, about 10 are Italian cultivars, most of which are dioecious, and they are mainly selected for either fiber production or medical cosmetic uses, although the monoecious varieties are more suitable for the production of hemp seeds. In any case, the main hemp varieties cultivated in Italy include Antal, Asso, Carma, Carmagnola, Carmagnola Selezionata, Carmaleonte, Codimono, Dioica 88, Eletta Campana, Fedora 19, Felina 32, Fibranova, Fibrante, Finola, Futura 75, Glecia, Gliana, Juzo 31, Kompolti, Superfibra, Tiborszallasi, Tisza, Uso 31, and Villanova. The Fibranova cultivar was developed in the 1950s as a cross between Bredemann Eletta and Carmagnola, the Bredemann Eletta variety was developed at the Max Planck Institut using hemp strains originating from Northern and Central Russia, while the Eletta Campana resulted from a cross between the Carmagnola landrace and German cultivars, most likely Fibridia.

Other hemp-derived products include oils used in cosmetics, wax, paint, soap, detergents, paper, packaging materials, pellet fuels for a clean combustion, as well as natural resins and fabrics that can be used for clothing due to their thermal properties, and for furnitures due to their resistance. Although hemp fabrics have historically been associated with rough and stiff clothes, nowadays they can be turned into light and soft textiles, after appropriate treatments and processing through dedicated machinery. Moreover, hemp paper is considered to be a more sustainable alternative to paper made from wood-pulp, since hemp stalks only take up to five months to mature, while hemp paper does not necessarily require toxic bleaching chemicals, and it can be recycled up to seven or eight times. Furthermore, as a good substitute for plastic due to their light weight and durability, hemp-derived products can be used in different sectors, such as car manufacturing, railway, aviation, and aerospace.

In February 2022, a collaboration protocol was signed between Coldiretti Toscana and the Vecchiano start-up CanapaFiliera, which aims to revamp the hemp industry in Tuscany. In particular, the agreement provides for 1,000 ha (10.0 km; 3.9 sq mi) of farm land between Lucca and Pisa to be dedicated to the production of high-quality hemp fiber, that would then be used in the paper industry, clothing industry, and sustainable architecture. More specifically, the start-up would provide the seeds to the agricultural businesses participating in the project, which would then manage the cultivation of hemp as a rotational crop between the months of March and July, as part of a circular economy model.

Food and beverages

In Italy, certified hemp plants can be used for both industrial and ornamental purposes, however food products can only be derived from the hemp seeds, since they have no THC content, while the consumption of hemp flowers and leaves is still prohibited. In particular, the production of hemp seeds for culinary purposes started to gain traction in the country after the Ministry of Health issued a decree in 2009, in which the lawfulness of both hemp seeds and their derivatives was recognized for such uses.

In any case, considering that the demand for hemp-based food was estimated in 2021 to have grown by 500% since 2017, the production chain derived from hemp could significantly grow the Italian food industry, which is worth 50 billion euros in exports alone and is considered one of the pillars of the Italian economy. In fact, approximately 80% of the hemp produced in Italy is reportedly destined to the food industry, with an estimated yeld for the production of hemp seeds between 350 kg/ha (312.3 lb/acre) and 650 kg/ha (579.9 lb/acre), while the remaining 20% is used for various industrial purposes, including green buildings, cosmetics, and the nutraceutical sector.

Furthermore, in terms of the nutritional value, hemp seeds contain all essential amino acids in optimal proportions and in an easily digestible form, as well as high levels of protein and considerable amounts of fibers, vitamins, Omega-3, and minerals; and the wide range of edible products includes biscuits, taralli, bread, flour, anti-inflammatory oil, ricotta, tofu, and beer. The elevated protein content also makes cannabis-based food a suitable meat replacement for vegetarians, while its intense flavour has even been used for gelato, chocolate bars, and pastries. In 2017, the first hemp wine from Europe started being produced on a small scale in the Marches, as a result of a local collaboration between the Cantina Monte Schiavo winery and the Canapa Verde agency. Although technically not classified as a wine, as far as the Italian law is concerned, the Canavì combines Verdicchio grapes and cannabis sativa plants with a 0.4% THC content, resulting in a flavored beverage that was inspired by the particularly sought-after and expensive marijuana-infused wines that can be found in California.

Construction materials

In regard to the construction industry, building materials that can be derived from hemp include mortar, plaster, finishing products, thermally insulating panels, bricks, and ecobricks, as well as hemp-cement and hemp-lime biocomposites. Moreover, hemp concrete is a carbon sequester, since the amount of carbon stored in the material is higher than the emissions generated during its production, and it continues to store carbon during the building's life. This could have significant applications in Italy, where the construction sector is worth 237 billion euros, and alone is responsible for 30% of the total CO₂ emissions in the country.

In 2016, a study by the ENEA research center in Brindisi highlighted how the use of hemp-based materials for sustainable buildings resulted in slower propagation of structure fires; higher transpiration and resistance to bacteria; as well as improved energy performances, since their lower thermal conductivity reduces the need for air conditioning, especially in the warm temperate areas of the Mediterranean region. In particular, hemp was shown to improve the termal insulation of bricks, with a 30% reduction in their thermal flux and a 20% reduction in their thermal transmittance, while its good permeability for water vapor allows to avoid condensation. As buildings are responsible for a large part of the national energy consumption in Italy, with further ENEA studies showing that households alone account for 45% of CO₂ emissions in the country, hemp-base materials constitute a significant innovation potential for the construction sector.

Soil decontamination

Illustrations depicting the root system of a 1.8 m tall cannabis sativa plant, acquired at the beginning of August, before flowering, in a field located near Klagenfurt, Austria.

Illustrations depicting the root system of a 1.8 m tall cannabis sativa plant, acquired at the beginning of August, before flowering, in a field located near Klagenfurt, Austria.

Another significant application of industrial cannabis is soil decontamination through phytoremediation, a process in which contaminants are absorbed by the fast-growing roots of hemp plants, which store the toxins or even transform them into a harmless substance, without the need of removing and processing large quantities of soil, as with more traditional methods. As a known hyperaccumulator, cannabis plants are particularly suitable for phytoremediation, since they are extremely good at absorbing heavy metals, pesticides, petroleum solvents, crude oil, and other potentially harmful chemicals, without causing harm to themselves. In particular, hemp roots can store heavy metals in higher quantities (e.g. more than 100 mg/kg in the case of cadmium), with the younger roots producing phytochelatins for detoxification after the excessive absorption of these metals. Examples of applications include the removal of radioactive strontium and cesium from areas affected by the Chernobyl nuclear disaster of 1986, for which the pilot project started in 1998; as well as the removal of toxic chemical dioxins from farm lands and grazing fields around the Ilva steel plant near Taranto, with the project starting in 2012 after the establishment in 2010 of an exclusion zone for grazing livestock up to 20 km (12.4 mi) from the plant, due to the high levels of dioxins, lead, nickel, and tens of other toxic substances in the ground. Other similar projects have been tested in several sites in Brescia, in Sardinia, and in the Land of Pyres near Naples.

Besides their presence in the soil either as natural elements or as a result of pollution, another anthropogenic source of heavy metals in some farm lands has been their continued historical use as a predominant pesticide, and all these factors could negatively affect the consumers of cannabis-derived products. For instance, in a 2023 study, marijuana users were found to have 22% higher levels of cadmium and 27% higher levels of lead in their blood, as well as 18% higher levels of cadmium and 21% higher levels of lead in their urine, with respect to non-users.

In 2017, several test sites were established in Sardinia by the Agris Sardegna agency, as part of the multidisciplinary CANOPAES project, to evaluate the use of hemp to remove heavy metals from farm lands contaminated by both industrial and mining waste, while also providing useful information regarding the cultivation of hemp in the semi-arid areas of southern Italy, namely the optimal sowing period and the best varieties to be used for the specific production aims (e.g. biomass, achenes, or inflorescences). The various experimental sites, each covering about 0.5 ha (5,000.0 m; 1.2 acres), were sampled beforehand and subjected to pedological assessment, and subsequently planted with the Uso 31, Felina 32, and Futura 75 hemp varieties, to study the crop's bio-morphological parameters. The different parts of the plants (i.e. roots, stalks, leaves, inflorescences, and seeds) were separately analyzed to determine their heavy metal concentrations at different stages, while part of the resulting biomass was used to study the production of bioenergy by means of anaerobic digestion. Although a certain sensitivity to water stress was noted, the cultivated varieties were able to complete their life cycle even in difficult environmental and agronomic conditions. Furthermore, the hemp plants were observed to translocate the heavy metals mainly into the leaves and roots, rather than the seeds or the stalk, with the latter having a wider range of industrial applications.

In 2023, a scientific study was published regarding the phytoremediation potentials of the monoecious Futura 75 and KC Dora hemp varieties, as well as the effects of the pollutants on the crop yield, after a two-year experiment carried out by the University of Catania analyzed test soils that were purposefully contaminated with different levels of three heavy metals, namely cadmium, lead, and nickel. The two cultivars were specifically selected because the late-ripening French Futura 75 is one of the most cultivated industrial hemp varieties in Southern Europe, due to its excellent acclimatization to high temperatures, while the Hungarian KC Dora can achieve high biomass and seed yield in a wide range of climatic conditions, including the Mediterranean climate. Furthermore, the three studied contaminants were chosen because they are the most abundant heavy metals from industrial waste in Italy, according to a report by the European Environmental Agency, which considered the period from 2007 to 2016. The research highlighted the capability of industrial hemp plants to translocate the contaminants from the soils to the aerial parts (i.e. above ground) of the plants, while also completing their life cycle until seed ripening even in heavily contaminated soils, although with different performances in terms of yield and tolerance to the different pollutants. In addition, the low concentration of heavy metals in the hemp seeds was noted to suggest that the same plants could be used afterwards as a source of biofuel, while the remaining biomass (i.e. stems and leaves) could be further converted into bioenergy.

Soil enrichment

Further environmental benefits of cannabis cultivation derive from the fact that, among the other commonly grown crops, hemp plants reportedly have one of the lowest impact on their surroundings, since in most cases they do not require herbicides, insecticides, or fungicides due to the lack of natural enemies and few harmful pests, thus resulting in a higher biodiversity in terms of the local wildlife and insects; they have a minimal need for fertilizers and necessitate far less water than cotton, so much so that the production of a single t-shirt made out of hemp requires less than 0.25 L (0.05 imp gal; 0.07 US gal) of water, as opposed to the estimated 2,700 L (590 imp gal; 710 US gal) of water needed for one made out of cotton; and they provide the soil with a good amount of organic matter, consisting of a significant amount of fallen foliage, as well as an extensive and deep-reaching root system. Given this significant soil enrichment, when turning the cultivation within a field from cannabis plants to other crops, the resulting yield tend to significantly increase with respect to more traditional crop rotations. For example, in some cases, the production of wheat can increase by as much as 20% with respect to what it would have been, had the same field previously been growing either grass or chard. Furthermore, hemp plants can help to break the cycle of diseases when used in crop rotation, their fast growth and shading capacity prevent the growth of weeds, and the dense foliage just three weeks after germination constitutes a natural soil cover, which reduces water loss and protects against soil erosion.

Hemp plants also consume a significant amount of CO₂, so much so that the gas is sometimes artificially added to indoor cultivations to increase the resulting yield. This carbon capture quality results in a significant plant growth rate, as much as 4 m (13.1 ft) in three months, and can have significant applications in the removal of CO₂ from the atmosphere, with a hemp field spanning just 1 ha (0.01 km; 2.47 acres) being able to sequester between 9 and 15 t of CO₂ after just five months. In fact, hemp is seen as a potential new protagonist of Italian agriculture, to achieve the objectives of EU 2030, which aim at a 40% decrease in greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990.

Plant diseases and pests

Despite the aforementioned lower need for pesticides with respect to other crops, hemp plants can still be threatened by a certain number of pests at different stages of their development. In regard to plant diseases, a few notable cases of fungal infection involving hemp plants were reported in Italy, which could potentially have an impact on the industrial cannabis sector. For example, in 2016, several cases of stem canker with branches dieback were identified in hemp crops located in the Province of Rovigo, in reportedly the first known case of Neofusicoccum parvum infecting cannabis sativa plants worldwide.

In 2019, symptoms of white root rot were identified on hemp plants of the Kompolti variety, during a sanitary survey carried out at a private farm in the Province of Naples. The infected plants were collected for further analyses at the CREA phytosanitary laboratory in Caserta, where death occurred in 10% of the cases, generally within 2–3 weeks after the appearance of the first symptoms, which subsequently deteriorated into yellowing, canopy wilt, as well as signs of roots covered with white mycelium and fan-like mycelium under the bark. The causal agent was isolated from small root segments and identified as the Rosellinia necatrix, in reportedly the first known European case of this fungus infecting hemp plants. As the surveyed farm is reported to have historically produced apples for over 30 years, an adaptation of the fungus to the new host has been hypothesized.

In 2021, during variety comparison trials carried out in Campania on seven of the hemp cultivars considered relevant for bast fiber production, a germination failure between 80% and 90% was observed during the emergence of seedlings, particularly with the Fibrante variety, which suggested the possible presence of seed-borne pathogens. Dedicated tests subsequently confirmed though DNA sequencing the presence of Alternaria rosae, in reportedly the first observed case of a seed-borne fungus affecting hemp plants. As Alternaria spp. produce a wide range of toxic metabolites, their presence would undermine the safety of the food derived form the infected seeds, while also negatively impacting the entire hemp supply chain.

See also

- Adult lifetime cannabis use by country

- Annual cannabis use by country

- Antiprohibitionists on Drugs

- History of cannabis

- History of cannabis in Italy

- History of medical cannabis

- Legality of cannabis

- Legality of cannabis by country

- Timeline of cannabis law

References

- "linkonline.it". Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2015.