| Dusky shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

Endangered (IUCN 3.1) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Carcharhinidae |

| Genus: | Carcharhinus |

| Species: | C. obscurus |

| Binomial name | |

| Carcharhinus obscurus (Lesueur, 1818) | |

| |

| Confirmed (dark blue) and suspected (light blue) range of the dusky shark | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Carcharhinus iranzae Fourmanoir, 1961 *ambiguous synonym | |

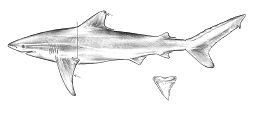

The dusky shark (Carcharhinus obscurus) is a species of requiem shark, in the family Carcharhinidae, occurring in tropical and warm-temperate continental seas worldwide. A generalist apex predator, the dusky shark can be found from the coast to the outer continental shelf and adjacent pelagic waters, and has been recorded from a depth of 400 m (1,300 ft). Populations migrate seasonally towards the poles in the summer and towards the equator in the winter, traveling hundreds to thousands of kilometers. One of the largest members of its genus, the dusky shark reaches more than 4 m (13 ft) in length and 350 kg (770 lb) in weight. It has a slender, streamlined body and can be identified by its short round snout, long sickle-shaped pectoral fins, ridge between the first and second dorsal fins, and faintly marked fins.

Adult dusky sharks have a broad and varied diet, consisting mostly of bony fishes, sharks and rays, and cephalopods, but also occasionally crustaceans, sea stars, bryozoans, sea turtles, marine mammals, carrion, and garbage. This species is viviparous with a three-year reproductive cycle; females bear litters of 3–14 young after a gestation period of 22–24 months, after which there is a year of rest before they become pregnant again. This shark, tied with the Spiny dogfish as a result is the animal with the longest gestation period. Females are capable of storing sperm for long periods, as their encounters with suitable mates may be few and far between due to their nomadic lifestyle and low overall abundance. Dusky sharks are one of the slowest-growing and latest-maturing sharks, not reaching adulthood until around 20 years of age.

Because of its slow reproductive rate, the dusky shark is very vulnerable to human-caused population depletion. This species is highly valued by commercial fisheries for its fins, used in shark fin soup, and for its meat, skin, and liver oil. It is also esteemed by recreational fishers. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed this species as Endangered worldwide and Vulnerable off the eastern United States, where populations have dropped to 15–20% of 1970s levels. The dusky shark is regarded as potentially dangerous to humans due to its large size, but there are few attacks attributable to it.

Taxonomy

French naturalist Charles Alexandre Lesueur published the first scientific description of the dusky shark in an 1818 issue of Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. He placed it in the genus Squalus and gave it the specific epithet obscurus (Latin for "dark" or "dim"), referring to its coloration. Subsequent authors have recognized this species as belonging to the genus Carcharhinus. Lesueur did not designate a type specimen, though he was presumably working from a shark caught in North American waters.

Many early sources gave the scientific name of the dusky shark as Carcharias (later Carcharhinus) lamiella, which originated from an 1882 account by David Starr Jordan and Charles Henry Gilbert. Although Jordan and Gilbert referred to a set of jaws that came from a dusky shark, the type specimen they designated was later discovered to be a copper shark (C. brachyurus). Therefore, C. lamiella is not considered a synonym of C. obscurus but rather of C. brachyurus. Other common names for this species include bay shark, black whaler, brown common gray shark, brown dusky shark, brown shark, common whaler, dusky ground shark, dusky whaler, river whaler, shovelnose, and slender whaler shark.

Phylogeny and evolution

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogenetic relationships of the dusky shark, based on allozyme sequences. |

Teeth belonging to the dusky shark are fairly well represented in the fossil record, though assigning Carcharhinus teeth to species can be problematic. Dusky shark teeth dating to the Miocene (23–5.3 Ma) have been recovered from the Kendeace and Grand Bay formations in Carriacou, the Grenadines, the Moghra Formation in Egypt, Polk County, Florida, and possibly Cerro La Cruz in northern Venezuela. Teeth dating to the Late Miocene or Early Pliocene (11.6-3.6 Ma) are abundant in the Yorktown Formation and the Pungo River, North Carolina, and from the Chesapeake Bay region; these teeth differ slightly from the modern dusky shark, and have often been misidentified as belonging to the oceanic whitetip shark (C. longimanus). Dusky shark teeth have also been recovered from the vicinity of two baleen whales in North Carolina, one preserved in Goose Creek Limestone dating to the Late Pliocene (c. 3.5 Ma), and the other in mud dating to the Pleistocene-Holocene (c. 12,000 years ago).

In 1982, Jack Garrick published a phylogenetic analysis of Carcharhinus based on morphology, in which he placed the dusky shark and the Galapagos shark (C. galapagensis) at the center of the "obscurus group". The group consisted of large, triangular-toothed sharks with a ridge between the dorsal fins, and also included the bignose shark (C. altimus), the Caribbean reef shark (C. perezi), the sandbar shark (C. plumbeus), and the oceanic whitetip shark. This interpretation was largely upheld by Leonard Compagno in his 1988 phenetic study, and by Gavin Naylor in his 1992 allozyme sequence study. Naylor was able to further resolve the interrelationships of the "ridge-backed" branch of Carcharhinus, finding that the dusky shark, Galapagos shark, oceanic whitetip shark, and blue shark (Prionace glauca) comprise its most derived clade.

Distribution and habitat

The range of the dusky shark extends worldwide, albeit discontinuously, in tropical and warm-temperate waters. In the western Atlantic Ocean, it is found from Massachusetts and the Georges Bank to southern Brazil, including the Bahamas and Cuba. In the eastern Atlantic Ocean, it has been reported from the western and central Mediterranean Sea, the Canary Islands, Cape Verde, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and possibly elsewhere including Portugal, Spain, Morocco, and Madeira. In the Indian Ocean, it is found off South Africa, Mozambique, and Madagascar, with sporadic records in the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and perhaps the Red Sea. In the Pacific Ocean, it occurs off Japan, mainland China and Taiwan, Vietnam, Australia, and New Caledonia in the west, and from southern California to the Gulf of California, around Revillagigedo, and possibly off northern Chile in the east. Records of dusky sharks from the northeastern and eastern central Atlantic, and around tropical islands, may in fact be of Galapagos sharks. Mitochondrial DNA and microsatellite evidence suggest that Indonesian and Australian sharks represent distinct populations.

Residing off continental coastlines from the surf zone to the outer continental shelf and adjacent oceanic waters, the dusky shark occupies an intermediate habitat that overlaps with its more specialized relatives, such as the inshore sandbar shark, the pelagic silky shark (C. falciformis) and oceanic whitetip shark, the deepwater bignose shark, and the islandic Galapagos shark and silvertip shark (C. albimarginatus). One tracking study in the northern Gulf of Mexico found that it spends most of its time at depths of 10–80 m (33–262 ft), while making occasional forays below 200 m (660 ft); this species has been known to dive as deep as 400 m (1,300 ft). It prefers water temperatures of 19–28 °C (66–82 °F), and avoids areas of low salinity such as estuaries.

The dusky shark is nomadic and strongly migratory, undertaking recorded movements of up to 3,800 km (2,400 mi); adults generally move longer distances than juveniles. Sharks along both coasts of North America shift northward with warmer summer temperatures, and retreat back towards the equator in winter. Off South Africa, young males and females over 0.9 m (3.0 ft) long disperse southward and northward respectively (with some overlap) from the nursery area off KwaZulu-Natal; they join the adults several years later by a yet-unidentified route. In addition, juveniles spend spring and summer in the surf zone and fall and winter in offshore waters, and as they approach 2.2 m (7.2 ft) in length begin to conduct a north-south migration between KwaZulu-Natal in the winter and the Western Cape in summer. Still-larger sharks, over 2.8 m (9.2 ft) long, migrate as far as southern Mozambique. Off Western Australia, adult and juvenile dusky sharks migrate towards the coast in summer and fall, though not to the inshore nurseries occupied by newborns.

Description

The dusky shark can be identified by its sickle-shaped first dorsal and pectoral fins, with the former positioned over the rear tips of the latter

The dusky shark can be identified by its sickle-shaped first dorsal and pectoral fins, with the former positioned over the rear tips of the latter

Upper and lower teeth

Upper and lower teeth

One of the largest members of its genus, the dusky shark commonly reaches a length of 3.2 m (10 ft) and a weight of 160–180 kg (350–400 lb); the maximum recorded length and weight are 4.2 m (14 ft) and 372 kg (820 lb) respectively. However, the maximum reported size of the species is 4.5 m (15 ft), while the maximum weight is reported to reach up to 500 kg (1,100 lb). Females grow larger than males. This shark has a slender, streamlined body with a broadly rounded snout no longer than the width of the mouth. The nostrils are preceded by barely developed flaps of skin. The medium-sized, circular eyes are equipped with nictitating membranes (protective third eyelids). The mouth has very short, subtle furrows at the corners and contains 13–15 (typically 14) tooth rows on either side of both jaws. The upper teeth are distinctively broad, triangular, and slightly oblique with strong, coarse serrations, while the lower teeth are narrower and upright, with finer serrations. The five pairs of gill slits are fairly long.

The large pectoral fins measure around one-fifth as long as the body, and have a falcate (sickle-like) shape tapering to a point. The first dorsal fin is of moderate size and somewhat falcate, with a pointed apex and a strongly concave rear margin; its origin lies over the pectoral fin free rear tips. The second dorsal fin is much smaller and is positioned about opposite the anal fin. A low dorsal ridge is present between the dorsal fins. The caudal fin is large and high, with a well-developed lower lobe and a ventral notch near the tip of the upper lobe. The dermal denticles are diamond-shaped and closely set, each bearing five horizontal ridges leading to teeth on the posterior margin. This species is bronzy to bluish gray above and white below, which extends onto the flanks as a faint lighter stripe. The fins, particularly the underside of the pectoral fins and the lower caudal fin lobe) darken towards the tips; this is more obvious in juveniles. Dusky sharks can be found at Redondo Beach, southern California to the Gulf of California, and to Ecuador. But sometimes rarely off southern California; common in tropics. Dusky sharks have a total length of at least 3.6 m (11.8 ft) or possibly to 4.2 m (13.8 ft). At birth, dusky sharks are about a length of 70–100 cm (27.6-39.3 in). In the surf zone, dusky sharks swim to a depth of 573 m (1,879 ft). Dusky sharks have a color of Gray or beige.

Biology and ecology

As an apex predator positioned at the highest level of the trophic web, the dusky shark is generally less abundant than other sharks that share its range. However, high concentrations of individuals, especially juveniles, can be found at particular locations. Adults are often found following ships far from land, such as in the Agulhas Current. A tracking study off the mouth of the Cape Fear River in North Carolina reported an average swimming speed of 0.8 km/h (0.50 mph). The dusky shark is one of the hosts of the sharksucker (Echeneis naucrates). Known parasites of this species include the tapeworms Anthobothrium laciniatum, Dasyrhynchus pacificus, Platybothrium kirstenae, Floriceps saccatus, Tentacularia coryphaenae, and Triloculatum triloculatum, the monogeneans Dermophthirius carcharhini and Loimos salpinggoides, the leech Stibarobdella macrothela, the copepods Alebion sp., Pandarus cranchii, P. sinuatus, and P. smithii, the praniza larvae of gnathiid isopods, and the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus).

Full-grown dusky sharks have no significant natural predators. Major predators of young sharks include the ragged tooth shark (Carcharias taurus), the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), the bull shark (C. leucas), and the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier). Off KwaZulu-Natal, the use of shark nets to protect beaches has reduced the populations of these large predators, leading to a dramatic increase in the number of juvenile dusky sharks (a phenomenon called "predator release"). In turn, the juvenile sharks have decimated populations of small bony fishes, with negative consequences for the biodiversity of the local ecosystem.

Feeding

The dusky shark is a generalist that takes a wide variety of prey from all levels of the water column, though it favors hunting near the bottom. A large individual can consume over a tenth of its body weight at a single sitting. The bite force exerted by a 2 m (6.6 ft) long dusky shark has been measured at 60 kg (130 lb) over the 2 mm (0.0031 in) area at the tip of a tooth. This is the highest figure thus far measured from any shark, though it also reflects the concentration of force at the tooth tip. Dense aggregations of young sharks, forming in response to feeding opportunities, have been documented in the Indian Ocean.

The known diet of the dusky shark encompasses pelagic fishes, including herring and anchovies, tuna and mackerel, billfish, jacks, needlefish and flyingfish, threadfins, hairtails, lancetfish, and lanternfish; demersal fishes, including mullets, porgies, grunts, and flatheads, eels, lizardfish, cusk eels, gurnards, and flatfish; reef fishes, including barracudas, goatfish, spadefish, groupers, scorpionfish, and porcupinefish; cartilaginous fishes, including dogfish, sawsharks, angel sharks, catsharks, thresher sharks, smoothhounds, smaller requiem sharks, sawfish, guitarfish, skates, stingrays, and butterfly rays; and invertebrates, including gastropods, cephalopods, decapod crustaceans, barnacles, and sea stars. Very rarely, the largest dusky sharks may also consume sea turtles, marine mammals (mainly as carrion), and human refuse.

In the northwestern Atlantic, around 60% of the dusky shark's diet consists of bony fishes, from over ten families with bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix) and summer flounder (Paralichthys dentatus) being especially important. Cartilaginous fishes, mainly skates and their egg cases, are the second-most important dietary component, while the lady crab (Ovalipes ocellatus) is also a relatively significant food source. In South African and Australian waters, bony fishes are again the most important prey type. Newborn and juvenile sharks subsist mainly on small pelagic prey such as sardines and squid; older sharks over 2 m (6.6 ft) long broaden their diets to include larger bony and cartilaginous fishes. The run of the southern African pilchard (Sardinops sagax), occurring off the eastern coast of South Africa every winter, is attended by medium and large-sized dusky sharks. Pregnant and post-partum females do not join, possibly because the energy cost of gestation leaves them unable to pursue such swift prey. One South African study reported that 0.2% of the sharks examined had preyed upon bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus).

Life history

Like other requiem sharks, the dusky shark is viviparous: the developing embryos are initially nourished by a yolk sac, which is converted into a placental connection to the mother once the yolk supply is exhausted. Mating occurs during spring in the northwestern Atlantic, while there appears to be no reproductive seasonality in other regions such as off South Africa. Females are capable of storing masses of sperm, possibly from multiple males, for months to years within their nidamental glands (an organ that secretes egg cases). This would be advantageous given the sharks' itinerant natures and low natural abundance, which would make encounters with suitable mates infrequent and unpredictable.

With a gestation period estimated at up to 22–24 months and a one-year resting period between pregnancies, female dusky sharks bear at most one litter of young every three years. Litter size ranges from 3 to 16, with 6 to 12 being typical, and does not correlate with female size. Sharks in the western Atlantic tend to produce slightly smaller litters than those from the southeastern Atlantic (averaging 8 versus 10 pups per litter). Depending on region, birthing may occur throughout the year or over a span of several months: newborn sharks have been reported from late winter to summer in the northwestern Atlantic, in summer and fall off Western Australia, and throughout the year with a peak in fall off southern Africa. Females move into shallow inshore habitats such as lagoons to give birth, as such areas offer their pups rich food supplies and shelter from predation (including from their own species), and leave immediately afterward. These nursery areas are known along the coasts of KwaZulu-Natal, southwestern Australia, western Baja California, and the eastern United States from New Jersey to North Carolina.

| Region | Male length and age at maturity | Female length and age at maturity |

|---|---|---|

| Northwestern Atlantic | 2.80 m (9.2 ft), 19 years | 2.84 m (9.3 ft), 21 years |

| Eastern South Africa | 2.80 m (9.2 ft), 19–21 years | 2.60–3.00 m (8.53–9.84 ft), 17–24 years |

| Indonesia | 2.80–3.00 m (9.19–9.84 ft), age unknown | 2.80 m (9.2 ft), age unknown |

| Western Australia | 2.65–2.80 m (8.7–9.2 ft), 18–23 years | 2.95–3.10 m (9.7–10.2 ft), 27–32 years |

Newborn dusky sharks measure 0.7–1.0 m (2.3–3.3 ft) long; pup size increases with female size, and decreases with litter size. There is evidence that females can determine the size at which their pups are born, so as to improve their chances of survival across better or worse environmental conditions. Females also provision their young with energy reserves, stored in a liver that comprises one-fifth of the pup's weight, which sustains the newborn until it learns to hunt for itself. The dusky shark is one of the slowest-growing shark species, reaching sexual maturity only at a substantial size and age (see table). Various studies have found growth rates to be largely similar across geographical regions and between sexes. The annual growth rate is 8–11 cm (3.1–4.3 in) over the first five years of life. The maximum lifespan is believed to be 40–50 years or more.

Human interactions

Danger to humans

The dusky shark is considered to be potentially dangerous to humans because of its large size, though little is known of how it behaves towards people underwater. As of 2009, the International Shark Attack File lists it as responsible for six attacks on people and boats, three of them unprovoked and one fatal. However, attacks attributed to this species off Bermuda and other islands were probably in reality caused by Galapagos sharks.

Shark nets

Shark nets used to protect beaches in South Africa and Australia entangle adult and larger juvenile dusky sharks in some numbers. From 1978 to 1999, an average of 256 individuals were caught annually in nets off KwaZulu-Natal; species-specific data is not available for nets off Australia.

In aquariums

Young dusky sharks adapt well to display in public aquariums.

Fishing

The dusky shark is one of the most sought-after species for shark fin trade, as its fins are large and contain a high number of internal rays (ceratotrichia). In addition, the meat is sold fresh, frozen, dried and salted, or smoked, the skin is made into leather, and the liver oil is processed for vitamins. Dusky sharks are taken by targeted commercial fisheries operating off eastern North America, southwestern Australia, and eastern South Africa using multi-species longlines and gillnets. The southwestern Australian fishery began in the 1940s and expanded in the 1970s to yield 500–600 tons per year. The fishery utilizes selective demersal gillnets that take almost exclusively young sharks under three years old, with 18–28% of all newborns captured in their first year. Demographic models suggest that the fishery is sustainable, provided that the mortality rate of sharks under 2 m (6.6 ft) long is under 4%.

In addition to commercial shark fisheries, dusky sharks are also caught as bycatch on longlines meant for tuna and swordfish (and usually kept for its valuable fins), and by recreational fishers. Large numbers of dusky sharks, mostly juveniles, are caught by sport fishers off South Africa and eastern Australia. This shark was once one of the most important species in the Florida trophy shark tournaments, before the population collapsed.

Conservation

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed this species as Endangered worldwide. The American Fisheries Society has assessed North American dusky shark populations as Vulnerable. Its very low reproductive rate renders the dusky shark extremely susceptible to overfishing.

Stocks off the eastern United States are severely overfished; a 2006 stock assessment survey by the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) showed that its population had dropped to 15–20% of 1970s levels. In 1997, the dusky shark was identified as a Species of Concern by the NMFS, meaning that it warranted conservation concern but there was insufficient information for listing on the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA). Commercial and recreational retention of dusky sharks was prohibited in 1998, but this has been of limited effectiveness due to high bycatch mortality on multi-species gear. In addition, some 2,000 dusky sharks were caught by recreational fishers in 2003 despite the ban. In 2005, North Carolina implemented a time/area closure to reduce the impact of recreational fishing. To aid conservation efforts, molecular techniques using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have been developed that can identify whether marketed shark parts (e.g. fins) are from prohibited species like the dusky shark, versus similar allowed species such as the sandbar shark.

The New Zealand Department of Conservation has classified the dusky shark as "Migrant" with the qualifier "Secure Overseas" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.

References

- ^ Rigby, C.L.; Barreto, R.; Carlson, J.; Fernando, D.; Fordham, S.; Francis, M.P.; Herman, K.; Jabado, R.W.; Liu, K.M.; Marshall, A.; Pacoureau, N.; Romanov, E.; Sherley, R.B.; Winker, H. (2019). "Carcharhinus obscurus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T3852A2872747. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T3852A2872747.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Compagno, L.J.V.; M. Dando & S. Fowler (2005). Sharks of the World. Princeton University Press. pp. 302–303. ISBN 978-0-691-12072-0.

- Lesueur, C.A. (May 1818). "Description of several new species of North American fishes (part 1)". Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 1 (2): 222–235.

- ^ Ebert, D.A. (2003). Sharks, Rays, and Chimaeras of California. University of California Press. pp. 160–162. ISBN 0-520-22265-2.

- ^ Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Food and Agricultural Organization. pp. 489–491. ISBN 92-5-101384-5.

- Jordan, D.S.; Gilbert, C.H. (July 3, 1882). "Description of a new shark (Carcharias lamiella) from San Diego, California". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 5 (269): 110–111. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.5-269.110.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Carcharhinus obscurus". FishBase. May 2009 version.

- ^ Naylor, G.J.P. (1992). "The phylogenetic relationships among requiem and hammerhead sharks: inferring phylogeny when thousands of equally most parsimonious trees result". Cladistics. 8 (4): 295–318. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1992.tb00073.x. hdl:2027.42/73088. PMID 34929961. S2CID 39697113.

- ^ Heim, B. and Bourdon, J. (April 20, 2009). Species from the Fossil Record: Carcharhinus obscurus. The Life and Times of Long Dead Sharks. Retrieved on April 29, 2010.

- Portell, R.W.; Hubbell, G.; Donovan, S.K.; Green, J.K.; Harper, D.A.T.; Pickerill, R. (2008). "Miocene sharks in the Kendeace and Grand Bay formations of Carriacou, The Grenadines, Lesser Antilles". Caribbean Journal of Science. 44 (3): 279–286. doi:10.18475/cjos.v44i3.a2. S2CID 87154947.

- Cook, T.D.; Murray, A.M.; Simons, E.L.; Attia, Y.S.; Chatrath, P. (February 8, 2010). "A Miocene selachian fauna from Moghra, Egypt". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. 22 (1–3): 78–87. doi:10.1080/08912960903249329. S2CID 128469722.

- Brown, R.C. (2008). Florida's Fossils: Guide to Location, Identification, and Enjoyment (third ed.). Pineapple Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-56164-409-4.

- Sanchez-Villagra, M.R.; Burnham, R.J.; Campbell, D.C.; Feldmann, R.M.; Gaffney, E.S.; Kay, R.F.; Lozsan, R.; Purdy R.; Thewissen, J.G.M. (September 2000). "A New Near-Shore Marine Fauna and Flora from the Early Neogene of Northwestern Venezuela". Journal of Paleontology. 74 (5): 957–968. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2000)074<0957:ANNSMF>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 130609225.

- Cicimurri, D.J.; Knight, J.L. (2009). "Two Shark-bitten Whale Skeletons from Coastal Plain Deposits of South Carolina". Southeastern Naturalist. 8 (1): 71–82. doi:10.1656/058.008.0107. S2CID 86113934.

- Garrick, J.A.f. (1982). Sharks of the genus Carcharhinus. NOAA Technical Report, NMFS Circ. 445: 1–194.

- Compagno, L.J.V. (1988). Sharks of the Order Carcharhiniformes. Princeton University Press. pp. 319–320. ISBN 0-691-08453-X.

- Ovenden, J.R.; Kashiwagi, T.; Broderick, D.; Giles, J.; Salini, J. (2009). "The extent of population genetic subdivision differs among four co-distributed shark species in the Indo-Australian archipelago". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 9: 40. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-40. PMC 2660307. PMID 19216767.

- Hoffmayer, E.R., Franks, J.S., Driggers, W.B. (III) and Grace, M.A. (March 26, 2009). "Movements and Habitat Preferences of Dusky (Carcharhinus obscurus) and Silky (Carcharhinus falciformis) Sharks in the Northern Gulf of Mexico: Preliminary Results." 2009 MTI Bird and Fish Tracking Conference Proceedings.

- ^ Van der Elst, R.; Borchert, P. (1993). A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of Southern Africa (third ed.). Struik. p. 39. ISBN 1-86825-394-5.

- ^ Knickle, C. Biological Profiles: Dusky Shark. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on May 18, 2009.

- Castro, Jose I. (28 July 2011). The Sharks of North America. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 445. ISBN 978-0-19-539294-4.

- Cooper, Steve (May 2007). Fishing Techniques. Australian Fishing Network. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-86513-106-1.

- ^ Natanson, L.J.; Casey, J.G. & Kohler, N.E. (1995). "Age and growth estimates for the dusky shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, in the western North Atlantic Ocean" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 93 (1): 116–126.

- McEachran, J.D.; Fechhelm, J.D. (1998). Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico: Myxiniformes to Gasterosteiformes. University of Texas Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-292-75206-7.

- ^ Last, P.R.; Stevens, J.D. (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia (second ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 269–270. ISBN 978-0-674-03411-2.

- Huish, M.T.; Benedict, C. (1977). "Sonic tracking of dusky sharks in Cape Fear River, North Carolina". Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society. 93 (1): 21–26.

- Schwartz, F.J. (Summer 2004). "Five species of sharksuckers (family Echeneidae) in North Carolina". Journal of the North Carolina Academy of Science. 120 (2): 44–49.

- Ruhnke, T.R.; Caira, J.N. (2009). "Two new species of Anthobothrium van Beneden, 1850 (Tetraphyllidea: Phyllobothriidae) from carcharhinid sharks, with a redescription of Anthobothrium laciniatum Linton, 1890". Systematic Parasitology. 72 (3): 217–227. doi:10.1007/s11230-008-9168-0. PMID 19189232. S2CID 1226830.

- Beveridge, I.; Campbell, R.A. (February 1993). "A revision of Dasyrhynchus Pintner (Cestoda, Trypanorhyncha), parasitic in elasmobranch and teleost fishes". Systematic Parasitology. 24 (2): 129–157. doi:10.1007/BF00009597. S2CID 6769785.

- Healy, C.J. (October 2003). "A revision of Platybothrium Linton, 1890 (Tetraphyllidea : Onchobothriidae), with a phylogenetic analysis and comments on host-parasite associations". Systematic Parasitology. 56 (2): 85–139. doi:10.1023/A:1026135528505. PMID 14574090. S2CID 944343.

- Linton, E. (1921). "Rhynchobothrium ingens spec. nov., a parasite of the dusky shark (Carcharhinus obscurus)". Journal of Parasitology. 8 (1): 22–32. doi:10.2307/3270938. JSTOR 3270938.

- Knoff, M.; De Sao Clemente, S.C.; Pinto, R.M.; Lanfredi, R.M.; Gomes, D.C. (April–June 2004). "New records and expanded descriptions of Tentacularia coryphaenae and Hepatoxylon trichiuri homeacanth trypanorhynchs (Eucestoda) from carcharhinid sharks from the State of Santa Catarina off-shore, Brazil". Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinaria. 13 (2): 73–80.

- Caira, J.N.; Jensen, K. (2009). "Erection of a new onchobothriid genus (Cestoda: Tetraphyllidea) and the description of five new species from whaler sharks (Carcharhinidae)". Journal of Parasitology. 95 (4): 924–940. doi:10.1645/GE-1963.1. hdl:1808/13336. PMID 20049998. S2CID 31178927.

- Bullard, S.A.; Dippenaar, S.M.; Hoffmayer, E.R.; Benz, G.W. (January 2004). "New locality records for Dermophthirius carcharhini (Monogenea : Microbothriidae) and Dermophthirius maccallumi and a list of hosts and localities for species of Dermophthirius". Comparative Parasitology. 71 (1): 78–80. doi:10.1654/4093. S2CID 85621860.

- MacCullum, G.A. (1917). "Some new forms of parasitic worms". Zoopathologica. 1 (2): 1–75.

- Yamauchi, T.; Ota, Y.; Nagasawa, K. (August 20, 2008). "Stibarobdella macrothela (Annelida, Hirudinida, Piscicolidae) from Elasmobranchs in Japanese Waters, with New Host Records". Biogeography. 10: 53–57.

- ^ Newbound, D.R.; Knott, B. (November 1999). "Parasitic copepods from pelagic sharks in Western Australia". Bulletin of Marine Science. 65 (3): 715–724.

- Jensen, C.; Schwartz, F.J. (December 1994). "Atlantic Ocean occurrences of the sea lamprey, Petromyzon marinus (Petromyzontiformes: Petromyzontidae), parasitizing sandbar, Carcharhinus plumbeus, and dusky, C. obscurus (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae), sharks off North and South Carolina". Brimleyana. 21: 69–76.

- Martin, R.A. A Place For Sharks. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on May 5, 2010.

- ^ Gelsleichter, J.; Musick, J.A.; Nichols, S. (February 1999). "Food habits of the smooth dogfish, Mustelus canis, dusky shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, Atlantic sharpnose shark, Rhizoprionodon terraenovae, and the sand tiger, Carcharias taurus, from the northwest Atlantic Ocean". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 54 (2): 205–217. doi:10.1023/A:1007527111292. S2CID 21850377.

- ^ Hussey, N.E.; Cocks, D.T.; Dudley, S.F.J.; McCarthy, I.D.; Wintner, S.P. (2009). "The condition conundrum: application of multiple condition indices to the dusky shark Carcharhinus obscurus". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 380: 199–212. Bibcode:2009MEPS..380..199H. doi:10.3354/meps07918.

- Martin, R.A. The Power of Shark Bites. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on August 31, 2009.

- Gubanov, E.P. (1988). "Morphological characteristics of the requiem shark, Carcharinus obscurus, of the Indian Ocean". Journal of Ichthyology. 28 (6): 68–73.

- "Carcharhinus obscurus (Shovelnose)". Animal Diversity Web.

- Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Goodreid, A.; McAuley, R.B. (2001). "Diet of three commercially important shark species from Western Australian waters". Marine and Freshwater Research. 52 (7): 975–985. doi:10.1071/MF01017.

- ^ Smale, M.J. (1991). "Occurrence and feeding of three shark species, Carcharhinus brachyurus, C. obscurus and Sphyrna zygaena, on the eastern Cape coast of South Africa". South African Journal of Marine Science. 11: 31–42. doi:10.2989/025776191784287808.

- Cockcroft, V.G.; Cliff, G.; Ross, G.J.B. (1989). "Shark predation on Indian Ocean bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus off Natal, South Africa". South African Journal of Zoology. 24 (4): 305–310. doi:10.1080/02541858.1989.11448168. S2CID 86281315.

- Pratt, H.L. (Jr.) (1993). "The storage of spermatozoa in the oviducal glands of western North Atlantic sharks". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 38 (1–3): 139–149. doi:10.1007/BF00842910. S2CID 25172842.

- ^ Natanson, L.J.; Kohler, N.E. (1996). "A preliminary estimate of age and growth of the dusky shark Carcharhinus obscurus from the South-West Indian Ocean, with comparisons to the western North Atlantic population". South African Journal of Marine Science. 17: 217–224. doi:10.2989/025776196784158572.

- Dudley, S.J.F.; Cliff, G.; Zungu, M.P.; Smale, M.J. (2005). "Sharks caught in the protective gillnets off KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. 10. The dusky shark Carcharhinus obscurus (LeSueur, 1818)". South African Journal of Marine Science. 27 (1): 107–127. doi:10.2989/18142320509504072. S2CID 85181390.

- ^ White, W.T. (2007). "Catch composition and reproductive biology of whaler sharks (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae) caught by fisheries in Indonesia". Journal of Fish Biology. 71 (5): 1512–1540. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01623.x.

- ^ Simpfendorfer, C.A.; McAuley, R.B.; Chidlow, J.; Unsworth, P. (2002). "Validated age and growth of the dusky shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, from Western Australian waters". Marine and Freshwater Research. 53 (2): 567–573. doi:10.1071/MF01131.

- McAuley, R.; Lenanton, R.; Chidlow, J.; Allison, R.; Heist, E. (2005). "Biology and stock assessment of the thickskin (sandbar) shark, Carcharhinus plumbeus, in Western Australia and further refinement of the dusky shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, stock assessment. Final FRDC Report - Project 2000/134" (PDF). Fisheries Western Australia Fisheries Research Report. 151: 1–132. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-28. Retrieved 2016-11-11.

- ^ Fowler, S.L.; Cavanagh, R.D.; Camhi, M.; Burgess, G.H.; Cailliet, G.M.; Fordham, S.V.; Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Musick, J.A. (2005). Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras: The Status of the Chondrichthyan Fishes. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. pp. 297–300. ISBN 2-8317-0700-5.

- Simpfendorfer, C.A. (Oct 2000). "Growth rates of juvenile dusky sharks, Carcharhinus obscurus (Lesueur, 1818), from southwestern Australia estimated from tag-recapture data". Fishery Bulletin. 98 (4): 811–822.

- ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark. International Shark Attack File, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. Retrieved on May 14, 2010.

- Species of Concern NOAA

- Species of Concern: Dusky Shark Archived 2010-08-03 at the Wayback Machine. (Jan. 6, 2009). NMFS Office of Protected Resources. Retrieved on May 18, 2009.

- Pank, M.; Stanhope, M.; Natanson, L.; Kohler, N. & Shivji, M. (May 2001). "Rapid and Simultaneous Identification of Body Parts from the Morphologically Similar Sharks Carcharhinus obscurus and Carcharhinus plumbeus (Carcharhinidae) Using Multiplex PCR". Marine Biotechnology. 3 (3): 231–240. doi:10.1007/s101260000071. PMID 14961360. S2CID 11342367.

- Duffy, Clinton A. J.; Francis, Malcolm; Dunn, M. R.; Finucci, Brit; Ford, Richard; Hitchmough, Rod; Rolfe, Jeremy (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand chondrichthyans (chimaeras, sharks and rays), 2016 (PDF). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. p. 9. ISBN 9781988514628. OCLC 1042901090.

External links

- Youtube video of Dusky Sharks at Shelly Beach in Sydney

- Carcharhinus obscurus, Dusky shark at FishBase

- Biological Profiles: Dusky Shark at Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Carcharhinus obscurus |

|

| Squalus obscurus | |

- IUCN Red List endangered species

- Carcharhinus

- Fish of the Eastern United States

- Fish of the Mediterranean Sea

- Fish of South Africa

- Fish of the Dominican Republic

- Pantropical fish

- Vulnerable fish

- Vulnerable biota of Africa

- Vulnerable fauna of Asia

- Vulnerable biota of Europe

- Vulnerable fauna of Oceania

- Vulnerable biota of South America

- Fish described in 1818