| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Centre" geometry – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In geometry, a centre (British English) or center (American English) (from Ancient Greek κέντρον (kéntron) 'pointy object') of an object is a point in some sense in the middle of the object. According to the specific definition of centre taken into consideration, an object might have no centre. If geometry is regarded as the study of isometry groups, then a centre is a fixed point of all the isometries that move the object onto itself.

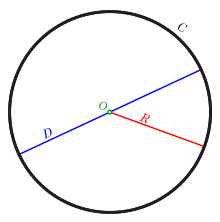

Circles, spheres, and segments

The centre of a circle is the point equidistant from the points on the edge. Similarly the centre of a sphere is the point equidistant from the points on the surface, and the centre of a line segment is the midpoint of the two ends.

Symmetric objects

For objects with several symmetries, the centre of symmetry is the point left unchanged by the symmetric actions. So the centre of a square, rectangle, rhombus or parallelogram is where the diagonals intersect, this is (among other properties) the fixed point of rotational symmetries. Similarly the centre of an ellipse or a hyperbola is where the axes intersect.

Triangles

Main article: Triangle centreSeveral special points of a triangle are often described as triangle centres:

- the circumcentre, which is the centre of the circle that passes through all three vertices;

- the centroid or centre of mass, the point on which the triangle would balance if it had uniform density;

- the incentre, the centre of the circle that is internally tangent to all three sides of the triangle;

- the orthocentre, the intersection of the triangle's three altitudes; and

- the nine-point centre, the centre of the circle that passes through nine key points of the triangle.

For an equilateral triangle, these are the same point, which lies at the intersection of the three axes of symmetry of the triangle, one third of the distance from its base to its apex.

A strict definition of a triangle centre is a point whose trilinear coordinates are f(a,b,c) : f(b,c,a) : f(c,a,b) where f is a function of the lengths of the three sides of the triangle, a, b, c such that:

- f is homogeneous in a, b, c; i.e., f(ta,tb,tc)=tf(a,b,c) for some real power h; thus the position of a centre is independent of scale.

- f is symmetric in its last two arguments; i.e., f(a,b,c)= f(a,c,b); thus position of a centre in a mirror-image triangle is the mirror-image of its position in the original triangle.

This strict definition excludes pairs of bicentric points such as the Brocard points (which are interchanged by a mirror-image reflection). As of 2020, the Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers lists over 39,000 different triangle centres.

Tangential polygons and cyclic polygons

A tangential polygon has each of its sides tangent to a particular circle, called the incircle or inscribed circle. The centre of the incircle, called the incentre, can be considered a centre of the polygon.

A cyclic polygon has each of its vertices on a particular circle, called the circumcircle or circumscribed circle. The centre of the circumcircle, called the circumcentre, can be considered a centre of the polygon.

If a polygon is both tangential and cyclic, it is called bicentric. (All triangles are bicentric, for example.) The incentre and circumcentre of a bicentric polygon are not in general the same point.

General polygons

See also: Quadrilateral § Remarkable points and lines in a convex quadrilateralThe centre of a general polygon can be defined in several different ways. The "vertex centroid" comes from considering the polygon as being empty but having equal masses at its vertices. The "side centroid" comes from considering the sides to have constant mass per unit length. The usual centre, called just the centroid (centre of area) comes from considering the surface of the polygon as having constant density. These three points are in general not all the same point.

Projective conics

In projective geometry every line has a point at infinity or "figurative point" where it crosses all the lines that are parallel to it. The ellipse, parabola, and hyperbola of Euclidean geometry are called conics in projective geometry and may be constructed as Steiner conics from a projectivity that is not a perspectivity. A symmetry of the projective plane with a given conic relates every point or pole to a line called its polar. The concept of centre in projective geometry uses this relation. The following assertions are from G. B. Halsted.

- The harmonic conjugate of a point at infinity with respect to the end points of a finite sect is the 'centre' of that sect.

- The pole of the straight at infinity with respect to a certain conic is the 'centre' of the conic.

- The polar of any figurative point is on the centre of the conic and is called a 'diameter'.

- The centre of any ellipse is within it, for its polar does not meet the curve, and so there are no tangents from it to the curve. The centre of a parabola is the contact point of the figurative straight.

- The centre of a hyperbola lies without the curve, since the figurative straight crosses the curve. The tangents from the centre to the hyperbola are called 'asymptotes'. Their contact points are the two points at infinity on the curve.

See also

- Centrepoint

- Chebyshev centre

- Fixed points of isometry groups in Euclidean space

- Instantaneous centre of rotation

References

- Algebraic Highways in Triangle Geometry Archived January 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Kimberling, Clark. "This is PART 20: Centers X(38001) - X(40000)". Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers.

- G. B. Halsted (1903) Synthetic Projective Geometry, #130, #131, #132, #139