| Disc herniation | |

|---|---|

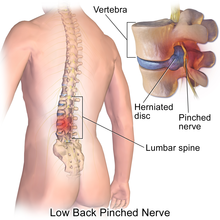

| Other names | Slipped disc, bulging disc, ruptured disc, herniated disc, prolapsed disc, herniated nucleus pulposus, lumbar disc herniation |

| |

| Specialty | Orthopedics, neurosurgery |

| Risk factors | Connective tissue disease |

A disc herniation or spinal disc herniation is an injury to the intervertebral disc between two vertebrae, usually caused by excessive strain or trauma to the spine. It may result in back pain, pain or sensation in different parts of the body, and physical disability. The most conclusive diagnostic tool for disc herniation is MRI, and treatments may range from painkillers to surgery. Protection from disc herniation is best provided by core strength and an awareness of body mechanics including good posture.

When a tear in the outer, fibrous ring of an intervertebral disc allows the soft, central portion to bulge out beyond the damaged outer rings, the disc is said to be herniated.

Disc herniation is frequently associated with age-related degeneration of the outer ring, known as the annulus fibrosus, but is normally triggered by trauma or straining by lifting or twisting. Tears are almost always posterolateral (on the back sides) owing to relative narrowness of the posterior longitudinal ligament relative to the anterior longitudinal ligament. A tear in the disc ring may result in the release of chemicals causing inflammation, which can result in severe pain even in the absence of nerve root compression.

Disc herniation is normally a further development of a previously existing disc protrusion, in which the outermost layers of the annulus fibrosus are still intact, but can bulge when the disc is under pressure. In contrast to a herniation, none of the central portion escapes beyond the outer layers. Most minor herniations heal within several weeks. Anti-inflammatory treatments for pain associated with disc herniation, protrusion, bulge, or disc tear are generally effective. Severe herniations may not heal of their own accord and may require surgery.

The condition may be referred to as a slipped disc, but this term is not accurate as the spinal discs are firmly attached between the vertebrae and cannot "slip" out of place.

Signs and symptoms

Typically, symptoms are experienced on one side of the body only.

Symptoms of a herniated disc can vary depending on the location of the herniation and the types of soft tissue involved. They can range from little or no pain, if the disc is the only tissue injured, to severe and unrelenting neck pain or low back pain that radiates into regions served by nerve roots which have been irritated or impinged by the herniated material. Often, herniated discs are not diagnosed immediately, as patients present with undefined pains in the thighs, knees, or feet.

Symptoms may include sensory changes such as numbness, tingling, paresthesia, and motor changes such as muscular weakness, paralysis, and affection of reflexes. If the herniated disc is in the lumbar region, the patient may also experience sciatica due to irritation of one of the nerve roots of the sciatic nerve. Unlike a pulsating pain or pain that comes and goes, which can be caused by muscle spasm, pain from a herniated disc is usually continuous or at least continuous in a specific position of the body.

It is possible to have a herniated disc without pain or noticeable symptoms if the extruded nucleus pulposus material doesn't press on soft tissues or nerves. A small-sample study examining the cervical spine in symptom-free volunteers found focal disc protrusions in 50% of participants, suggesting that a considerable part of the population might have focal herniated discs in their cervical region that do not cause noticeable symptoms.

A herniated disc in the lumbar spine may cause radiating nerve pain in the lower extremities or groin area and may sometimes be associated with bowel or bladder incontinence.

Typically, symptoms are experienced only on one side of the body, but if a herniation is very large and presses on the nerves on both sides within the spinal column or the cauda equina, both sides of the body may be affected, often with serious consequences. Compression of the cauda equina can cause permanent nerve damage or paralysis which can result in loss of bowel and bladder control and sexual dysfunction. This disorder is called cauda equina syndrome. Other complications include chronic pain.

Cause

When the spine is straight, such as in standing or lying down, internal pressure is equalized on all parts of the discs. While sitting or bending to lift, internal pressure on a disc can move from 1.2 bar (17 psi) (lying down) to over 21 bar (300 psi) (lifting with a rounded back). Herniation of the contents of the disc into the spinal canal often occurs when the anterior side (stomach side) of the disc is compressed while sitting or bending forward, and the contents (nucleus pulposus) get pressed against the tightly stretched and thinned membrane (annulus fibrosus) on the posterior side (back side) of the disc. The combination of membrane-thinning from stretching and increased internal pressure (14 to 21 bar (200 to 300 psi)) can result in the rupture of the confining membrane. The jelly-like contents of the disc then move into the spinal canal, pressing against the spinal nerves, which may produce intense and potentially disabling pain and other symptoms.

Some authors favour degeneration of the intervertebral disc as the major cause of spinal disc herniation and cite trauma as a minor cause. Disc degeneration occurs both in degenerative disc disease and aging. With degeneration, the disc components – the nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus – become exposed to altered loads. Specifically, the nucleus becomes fibrous and stiff and less able to bear load. Excess load is transferred to the annulus, which may then develop fissures as a result. If the fissures reach the periphery of the annulus, the nuclear material can pass through as a disc herniation.

Mutations in several genes have been implicated in intervertebral disc degeneration. Probable candidate genes include type I collagen (sp1 site), type IX collagen, vitamin D receptor, aggrecan, asporin, MMP3, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6 polymorphisms. Mutation in genes – such as MMP2 and THBS2 – that encode for proteins and enzymes involved in the regulation of the extracellular matrix has been shown to contribute to lumbar disc herniation.

Disc herniations can result from general wear and tear, such as weightlifting training, constant sitting or squatting, driving, or a sedentary lifestyle. Herniations can also result from the lifting of heavy loads.

Professional athletes, especially those playing contact sports, such as American football, Rugby, ice hockey, and wrestling, are known to be prone to disc herniations as well as some limited contact sports that require repetitive flexion and compression such as soccer, baseball, basketball, and volleyball. Within athletic contexts, herniation is often the result of sudden blunt impacts against, or abrupt bending or torsional movements of, the lower back.

Pathophysiology

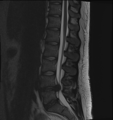

The majority of disc herniations occur in the lumbar spine (95% at L4–L5 or L5–S1). The second most common site is the cervical region (C5–C6, C6–C7). The thoracic region accounts for only 1–2% of cases. Herniations usually occur postero-laterally, at the points where the annulus fibrosus is relatively thin and is not reinforced by the posterior or anterior longitudinal ligament. In the cervical spine, a symptomatic postero-lateral herniation between two vertebrae will impinge on the nerve which exits the spinal canal between those two vertebrae on that side. So, for example, a right postero-lateral herniation of the disc between vertebrae C5 and C6 will impinge on the right C6 spinal nerve. The rest of the spinal cord, however, is oriented differently, so a symptomatic postero-lateral herniation between two vertebrae will impinge on the nerve exiting at the next intervertebral level down.

Lumbar disc herniation

Lumbar disc herniations occur in the back, most often between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebral bodies or between the fifth and the sacrum. Here, symptoms can be felt in the lower back, buttocks, thigh, anal/genital region (via the perineal nerve), and may radiate into the foot and/or toe. The sciatic nerve is the most commonly affected nerve, causing symptoms of sciatica. The femoral nerve can also be affected and cause the patient to experience a numb, tingling feeling throughout one or both legs and even feet or a burning feeling in the hips and legs. A herniation in the lumbar region often compresses the nerve root exiting at the level below the disc. Thus, a herniation of the L4–5 disc compresses the L5 nerve root, only if the herniation is posterolateral.

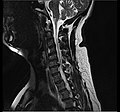

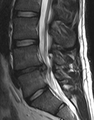

Cervical disc herniation

Cervical disc herniations occur in the neck, most often between the fifth and sixth (C5–6) and the sixth and seventh (C6–7) cervical vertebral bodies. There is an increased susceptibility amongst older (60+) patients to herniations higher in the neck, especially at C3–4. Symptoms of cervical herniations may be felt in the back of the skull, the neck, shoulder girdle, scapula, arm, and hand. The nerves of the cervical plexus and brachial plexus can be affected.

Intradural disc herniation

Intradural disc herniation occurs when the disc material crosses the dura mater and enters the thecal sac. It is a rare form of disc herniation with an incidence of 0.2–2.2%. Pre-operative imaging can be helpful for diagnosis, but intra-operative findings are required for confirmation.

Inflammation

It is increasingly recognized that back pain resulting from disc herniation is not always due solely to nerve compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots, but may also be caused by chemical inflammation. There is evidence that points to a specific inflammatory mediator in back pain: an inflammatory molecule, called tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF), is released not only by a herniated disc, but also in cases of disc tear (annulus tear) by facet joints, and in spinal stenosis. In addition to causing pain and inflammation, TNF may contribute to disc degeneration.

Diagnosis

Terminology

Terms commonly used to describe the condition include herniated disc, prolapsed disc, ruptured disc, and slipped disc. Other conditions that are closely related include disc protrusion, radiculopathy (pinched nerve), sciatica, disc disease, disc degeneration, degenerative disc disease, and black disc (a totally degenerated spinal disc).

The popular term slipped disc is a misnomer, as the intervertebral discs are tightly sandwiched between two vertebrae to which they are attached, and cannot actually "slip", or even get out of place. The disc is actually grown together with the adjacent vertebrae and can be squeezed, stretched and twisted, all in small degrees. It can also be torn, ripped, herniated, and degenerated, but it cannot "slip". Some authors consider that the term slipped disc is harmful, as it leads to an incorrect idea of what has occurred and thus of the likely outcome. However, during growth, one vertebral body can slip relative to an adjacent vertebral body, a deformity called spondylolisthesis.

Spinal disc herniation is known in Latin as prolapsus disci intervertebralis.

- Click images to see larger versions

-

Lumbar disc lesions, classification

Lumbar disc lesions, classification

-

Normal situation and spinal disc herniation in cervical vertebrae

Normal situation and spinal disc herniation in cervical vertebrae

-

Illustration depicting herniated disc and spinal nerve compression

Illustration depicting herniated disc and spinal nerve compression

-

Nucleus herniating through tear in annulus (with MRI)

Nucleus herniating through tear in annulus (with MRI)

-

Illustration showing disc degeneration, prolapse, extrusion and sequestration

Illustration showing disc degeneration, prolapse, extrusion and sequestration

Physical examination

Diagnosis of spinal disc herniation is made by a practitioner on the basis of a patient's history and symptoms, and by physical examination. During an evaluation, tests may be performed to confirm or rule out other possible causes with similar symptoms – spondylolisthesis, degeneration, tumors, metastases and space-occupying lesions, for instance – as well as to evaluate the efficacy of potential treatment options.

Straight leg raise

The straight leg raise is often used as a preliminary test for possible disc herniation in the lumbar region. A variation is to lift the leg while the patient is sitting. However, this reduces the sensitivity of the test. A Cochrane review published in 2010 found that individual diagnostic tests including the straight leg raising test, absence of tendon reflexes, or muscle weakness were not very accurate when conducted in isolation.

Spinal imaging

- Projectional radiography (X-ray imaging). Traditional plain X-rays are limited in their ability to image soft tissues such as discs, muscles, and nerves, but they are still used to confirm or exclude other possibilities such as tumors, infections, fractures, etc. In spite of their limitations, X-rays play a relatively inexpensive role in confirming the suspicion of the presence of a herniated disc. If a suspicion is thus strengthened, other methods may be used to provide final confirmation.

-

Narrowed space between L5 and S1 vertebrae, indicating probable prolapsed intervertebral disc – a classic picture

Narrowed space between L5 and S1 vertebrae, indicating probable prolapsed intervertebral disc – a classic picture

- Computed tomographyscan is the most sensitive imaging modality to examine the bony structures of the spine. CT imaging allows for the evaluation of calcified herniated discs or any pathological process that may result in bone loss or destruction. It is deficient for the visualization of nerve roots, making it unsuitable in the diagnoses of radiculopathy.

- Magnetic resonance imaging is the gold standard study for confirming a suspected LDH. With a diagnostic accuracy of 97%, it is the most sensitive study to visualize a herniated disc due to its significant ability in soft tissue visualization. MRI also has higher inter-observer reliability than other imaging modalities. It suggests disc herniation when it shows an increased T2-weighted signal at the posterior 10% of the disc. Degenerative disc diseases have shown a correlation with Modic type 1 changes. When evaluating for postoperative lumbar radiculopathies, the recommendation is that the MRI is performed with contrast unless otherwise contraindicated. MRI is more effective than CT in distinguishing inflammatory, malignant, or inflammatory etiologies of LDH. It is indicated relatively early in the course of evaluation (<8 weeks) when the patient presents with relative indications like significant pain, neurological motor deficits, and cauda equina syndrome. Diffusion tensor imaging is a type of MRI sequence used for detecting microstructural changes in the nerve root. It may be beneficial in understanding the changes that occur after herniated lumbar disc compresses a nerve root, and might help in differentiating the patients that need surgical intervention. In patients with a high suspicion of radiculopathy due to lumbar disc herniation, yet the MRI is equivocal or negative, nerve conduction studies are indicated. T2-weighted images allow for clear visualization of protruded disc material in the spinal canal.

-

MRI scan of cervical disc herniation between C5 and C6 vertebrae

MRI scan of cervical disc herniation between C5 and C6 vertebrae

-

MRI scan of cervical disc herniation between C6 and C7 vertebrae

MRI scan of cervical disc herniation between C6 and C7 vertebrae

-

MRI scan of large herniation (on the right) of the disc between L4 and L5 vertebrae

MRI scan of large herniation (on the right) of the disc between L4 and L5 vertebrae

-

A rather severe herniation of the L4–L5 disc

A rather severe herniation of the L4–L5 disc

-

Example of a herniated disc at L5–S1 in the lumbar spine

Example of a herniated disc at L5–S1 in the lumbar spine

- Myelography. An X-ray of the spinal canal following injection of a contrast material into the surrounding cerebrospinal fluid spaces will reveal displacement of the contrast material. It can show the presence of structures that can cause pressure on the spinal cord or nerves, such as herniated discs, tumors, or bone spurs. Because myelography involves the injection of foreign substances, MRI scans are now preferred for most patients. Myelograms still provide excellent outlines of space-occupying lesions, especially when combined with CT scanning (CT myelography). CT myelography is the imaging modality of choice to visualize herniated discs in patients with contraindications for an MRI. However, due to its invasiveness, the assistance of a trained radiologist is required. Myelography is associated with risks like post-spinal headache, meningeal infection, and radiation exposure. Recent advances with a multidetector CT scan have made the diagnostic level of it nearly equal to the MRI.

- The presence and severity of myelopathy can be evaluated by means of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a neurophysiological method that measures the time required for a neural impulse to cross the pyramidal tracts, starting from the cerebral cortex and ending at the anterior horn cells of the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar spinal cord. This measurement is called the central conduction time (CCT). TMS can aid physicians to:

- determine if myelopathy exists

- identify the level of the spinal cord where myelopathy is located. This is especially useful in cases where more than two lesions may be responsible for the clinical symptoms and signs, such as in patients with two or more cervical disc hernias

- assess the progression of myelopathy with time, for example before and after cervical spine surgery

- TMS can also help in the differential diagnosis of different causes of pyramidal tract damage.

- Electromyography and nerve conduction studies (EMG/NCS) measure the electrical impulses along nerve roots, peripheral nerves, and muscle tissue. Tests can indicate if there is ongoing nerve damage, if the nerves are in a state of healing from a past injury, or if there is another site of nerve compression. EMG/NCS studies are typically used to pinpoint the sources of nerve dysfunction distal to the spine.

Differential diagnosis

Tests may be required to distinguish spinal disc herniations from other conditions with similar symptoms.

- Discogenic pain

- Mechanical pain

- Myofascial pain

- Abscess

- Aortic dissection

- Discitis or osteomyelitis

- Hematoma

- Mass lesion or malignancy

- Benign tumor like neurinoma or meningeoma

- Myocardial infarction

- Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

- Spinal stenosis

- Spondylosis or spondylolisthesis

Treatment

In the majority of cases spinal disc herniation can be treated successfully conservatively, without surgical removal of the herniated material. Sciatica is a set of symptoms associated with lumbar disc herniation. A study on sciatica showed that about one-third of patients with sciatica recover within two weeks after presentation using conservative measures alone, and about three-quarters of patients recovered after three months of conservative treatment. However, sciatica may also less commonly be caused by nerve compression by muscles, tumors and other masses, and the study did not indicate the number of individuals with sciatica that had disc herniations.

Initial treatment usually consists of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), but long-term use of NSAIDs for people with persistent back pain is complicated by their possible cardiovascular and gastrointestinal toxicity.

Epidural corticosteroid injections provide a slight and questionable short-term improvement for those with sciatica, but are of no long-term benefit. Complications occur in up to 17% of cases when injections are performed on the neck, though most are minor. In 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggested that the "injection of corticosteroids into the epidural space of the spine may result in rare but serious adverse events, including loss of vision, stroke, paralysis, and death", and that "the effectiveness and safety of epidural administration of corticosteroids have not been established, and FDA has not approved corticosteroids for this use".

Lumbar disc herniation (LDH)

Non-surgical methods of treatment are usually attempted first. Pain medications may be prescribed to alleviate acute pain and allow the patient to begin exercising and stretching. There are a number of non-surgical methods used in attempts to relieve the condition. They are considered indicated, contraindicated, relatively contraindicated, or inconclusive, depending on the safety profile of their risk–benefit ratio and on whether they may or may not help:

Indicated

- Education on proper body mechanics

- Physical therapy to address mechanical factors, and may include modalities to temporarily relieve pain (i.e. traction, electrical stimulation, massage)

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Weight control

- Spinal manipulation. Moderate quality evidence suggests that spinal manipulation is more effective than placebo for the treatment of acute (less than 3 months duration) lumbar disc herniation and acute sciatica. The same study also found "low to very low" evidence for its usefulness in treating chronic lumbar symptoms (more than 3 months) and "the quality of evidence for ... cervical spine-related extremity symptoms of any duration is low or very low". A 2006 review of published research states that spinal manipulation "is likely to be safe when used by appropriately-trained practitioners", and research currently suggests that spinal manipulation is safe for the treatment of disc-related pain.

Contraindicated

- Spinal manipulation is contraindicated when the etiology of the herniation is the result of a Motor Vehicle Collision (MVC)

- Spinal manipulation is contraindicated for disc herniations when there are progressive neurological deficits such as with cauda equina syndrome.

- A review of non-surgical spinal decompression found shortcomings in most published studies and concluded that there was only "very limited evidence in the scientific literature to support the effectiveness of non-surgical spinal decompression therapy". Its use and marketing have been very controversial.

Surgery

Surgery may be useful when a herniated disc is causing significant pain radiating into the leg, significant leg weakness, bladder problems, or loss of bowel control.

- Discectomy (the partial removal of a disc that is causing leg pain) can provide pain relief sooner than non-surgical treatments.

- Small endoscopic discectomy (called nano-endoscopic discectomy) is non-invasive and does not cause failed back syndrome.

- Invasive microdiscectomy with a one-inch skin opening has not been shown to result in a significantly different outcome from larger-opening discectomy with respect to pain. It might however have less risk of infection.

- Failed back syndrome is a significant, potentially disabling, result that can arise following invasive spine surgery to treat disc herniation. Smaller spine procedures such as endoscopic transforaminal lumbar discectomy cannot cause failed back syndrome, because no bone is removed.

- The presence of cauda equina syndrome (in which there is incontinence, weakness, and genital numbness) is considered a medical emergency requiring immediate attention and possibly surgical decompression.

When different forms of surgical treatments including (discetomy, microdiscectomy, and chemonucleolysis) were compared evidence was suggestive rather than conclusive. A Cochrane review from 2007 reported: "surgical discectomy for carefully selected patients with sciatica due to a prolapsed lumbar disc appears to provide faster relief from the acute attack than non‐surgical management. However, any positive or negative effects on the lifetime natural history of the underlying disc disease are unclear. Microdiscectomy gives broadly comparable results to standard discectomy. There is insufficient evidence on other surgical techniques to draw firm conclusions." Regarding the role of surgery for failed medical therapy in people without a significant neurological deficit, a Cochrane review concluded that "limited evidence is now available to support some aspects of surgical practice".

Following surgery, rehabilitation programs are often implemented. There is wide variation in what these programs entail. A Cochrane review found low- to very low-quality evidence that patients who participated in high-intensity exercise programs had slightly less short term pain and disability compared to low-intensity exercise programs. There was no difference between supervised and home exercise programs.

Epidemiology

Disc herniation can occur in any disc in the spine, but the two most common forms are lumbar disc herniation and cervical disc herniation. The former is the most common, causing low back pain (lumbago) and often leg pain as well, in which case it is commonly referred to as sciatica. Lumbar disc herniation occurs 15 times more often than cervical (neck) disc herniation, and it is one of the most common causes of low back pain. The cervical discs are affected 8% of the time and the upper-to-mid-back (thoracic) discs only 1–2% of the time.

The following locations have no discs and are therefore exempt from the risk of disc herniation: the upper two cervical intervertebral spaces, the sacrum, and the coccyx. Most disc herniations occur when a person is in their thirties or forties when the nucleus pulposus is still a gelatin-like substance. With age the nucleus pulposus changes ("dries out") and the risk of herniation is greatly reduced. After age 50 or 60, osteoarthritic degeneration (spondylosis) or spinal stenosis are more likely causes of low back pain or leg pain.

- 4.8% of males and 2.5% of females older than 35 experience sciatica during their lifetime.

- Of all individuals, 60% to 80% experience back pain during their lifetime.

- In 14%, pain lasts more than two weeks.

- Generally, males have a slightly higher incidence than females.

Prevention

Because there are various causes of back injuries, prevention must be comprehensive. Back injuries are predominant in manual labor, so the majority of low back pain prevention methods have been applied primarily toward biomechanics. Prevention must come from multiple sources such as education, proper body mechanics, and physical fitness.

Education

Education should emphasize not lifting beyond one's capabilities and giving the body a rest after strenuous effort. Over time, poor posture can cause the intervertebral disc to tear or become damaged. Striving to maintain proper posture and body alignment will aid in preventing disc degradation.

Exercise

Exercises that enhance back strength may also be used to prevent back injuries. Back exercises include the prone push-ups/press-ups, upper back extension, transverse abdominis bracing, and floor bridges. If pain is present in the back, it can mean that the stabilization muscles of the back are weak and a person needs to train the trunk musculature. Other preventative measures are to lose weight and not to work oneself past fatigue. Signs of fatigue include shaking, poor coordination, muscle burning, and loss of the transverse abdominal brace. Heavy lifting should be done with the legs performing the work, and not the back.

Swimming is a common tool used in strength training. The usage of lumbar-sacral support belts may restrict movement at the spine and support the back during lifting.

Research

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2022) |

Future treatments may include stem cell therapy.

See also

- Sciatica

- Radiculopathy

- Nerve compression syndrome

- Inflammation

- Neuroinflammation

- Discectomy

- Failed back surgery syndrome

- Intervetebral disc

- Herniation

- Low back pain

- Degenerative disc disease

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Spinal stenosis

References

- "Herniated disk". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- "Backache from Occiput to Coccyx | Home Page". www.macdonaldpublishing.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-16. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- Moore, Keith L. (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy. A. M. R. Agur, Arthur F., II Dalley (8 ed.). Philadelphia. pp. 98–108. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3. OCLC 978362025. Archived from the original on 2021-03-01. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Windsor, Robert E (2006). "Frequency of asymptomatic cervical disc protrusions". Cervical Disc Injuries. eMedicine. Archived from the original on 2009-01-08. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- Ernst CW, Stadnik TW, Peeters E, Breucq C, Osteaux MJ (Sep 2005). "Prevalence of annular tears and disc herniations on MR images of the cervical spine in symptom free volunteers". Eur J Radiol. 55 (3): 409–14. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.11.003. PMID 16129249.

- "Prolapsed Disc Arizona Pain". arizonapain.com. Archived from the original on 2015-02-12. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- Simeone, F.A.; Herkowitz, H.N.; Garfin (2006). Rothman-Simeone, The Spine. ISBN 9780721647777.

- ^ Del Grande F, Maus TP, Carrino JA (July 2012). "Imaging the intervertebral disk: age-related changes, herniations, and radicular pain". Radiol. Clin. North Am. 50 (4): 629–49. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2012.04.014. PMID 22643389.

- ^ Anjankar SD, Poornima S, Raju S, Jaleel M, Bhiladvala D, Hasan Q. Degenerated intervertebral disc prolapse and its association of collagen I alpha 1 Spl gene polymorphism: A preliminary case control study of Indian population. Indian J Orthop 2015;49:589-94

- Kawaguchi, Y. (2018). "Genetic background of degenerative disc disease in the lumbar spine". Spine Surgery and Related Research. 2 (2): 98–112. doi:10.22603/ssrr.2017-0007. PMC 6698496. PMID 31440655.

- Hirose, Yuichiro; et al. (May 2008). "A Functional Polymorphism in THBS2 that Affects Alternative Splicing and MMP Binding Is Associated with Lumbar-Disc Herniation". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (5): 1122–1129. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.03.013. PMC 2427305. PMID 18455130.

- Shimozaki, K.; Nakase, J.; Yoshioka, K.; Takata, Y.; Asai, K.; Kitaoka, K.; Tsuchiya, H. (2018). "Incidence rates and characteristics of abnormal lumbar findings and low back pain in child and adolescent weightlifter: A prospective three-year cohort study". PLOS ONE. 13 (10): e0206125. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1306125S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206125. PMC 6205614. PMID 30372456.

- Videman, T.; Sarna, S.; Battié, M. C.; Koskinen, S.; Gill, K.; Paananen, H.; Gibbons, L. (1995). "The long-term effects of physical loading and exercise lifestyles on back-related symptoms, disability, and spinal pathology among men - PubMed". Spine. 20 (6): 699–709. doi:10.1097/00007632-199503150-00011. PMID 7604346. S2CID 5983201. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- Kraemer J (March 1995). "Natural course and prognosis of intervertebral disc diseases. International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine Seattle, Washington, June 1994". Spine. 20 (6): 635–9. doi:10.1097/00007632-199503150-00001. PMID 7604337.

- "Herniated disk: 6 safe exercises and what to avoid". Medical News Today. 28 January 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-12-24. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- "What is the physical toll of playing rugby?". September 2015. Archived from the original on 2021-02-27. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- Ball, J. R.; Harris, C. B.; Lee, J.; Vives, M. J. (2019). "Lumbar Spine Injuries in Sports: Review of the Literature and Current Treatment Recommendations". Sports Medicine - Open. 5 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/s40798-019-0199-7. PMC 6591346. PMID 31236714.

- Hsu, Wellington K. (August 2010). "Lumbar and Cervical Disk Herniations in NFL Players: Return to Action". Orthopedics. 33 (8): 566–568. doi:10.3928/01477447-20100625-18. PMID 20704153.

- Earhart, Jeffrey S.; Roberts, David; Roc, Gilbert; Gryzlo, Stephen; Hsu, Wellington (January 2012). "Effects of Lumbar Disk Herniation on the Careers of Professional Baseball Players". Orthopedics. 35 (1): 43–49. doi:10.3928/01477447-20111122-40. PMID 22229920.

- Bartolozzi, C.; Caramella, D.; Zampa, V.; Dal Pozzo, G.; Tinacci, E.; Balducci, F. (1991). "[The incidence of disk changes in volleyball players. The magnetic resonance findings] - PubMed". La Radiologia Medica. 82 (6): 757–60. PMID 1788427. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ Moore, Keith L. Moore, Anne M.R. Agur; in collaboration with and with content provided by Arthur F. Dalley II; with the expertise of medical illustrator Valerie Oxorn and the developmental assistance of Marion E. (2007). Essential clinical anatomy (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-7817-6274-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lumbar herniation at eMedicine

- Al-Ryalat, Nosaiba Tawfik; Saleh, Saif Aldeen; Mahafza, Walid Sulaiman; Samara, Osama Ahmad; Ryalat, Abdee Tawfiq; Al-Hadidy, Azmy Mohammad (March 2017). "Myelopathy associated with age-related cervical disc herniation: a retrospective review of magnetic resonance images". Annals of Saudi Medicine. 37 (2): 130–137. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2017.130. ISSN 0975-4466. PMC 6150546. PMID 28377542.

- "Symptoms of Herniated Cervical Disc". Archived from the original on 2016-05-16. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- Cervical herniation at eMedicine

- Kobayashi, K (October 2014). "Intradural disc herniation: Radiographic findings and surgical results with a literature review". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 125: 47–51. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.06.033. PMID 25086430. S2CID 32978237.

- ^ Peng B, Wu W, Li Z, Guo J, Wang X (Jan 2007). "Chemical radiculitis". Pain. 127 (1–2): 11–6. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.034. PMID 16963186. S2CID 45814193.

- Marshall LL, Trethewie ER (Aug 1973). "Chemical irritation of nerve-root in disc prolapse". Lancet. 2 (7824): 320. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(73)90818-0. PMID 4124797.

- McCarron RF, Wimpee MW, Hudkins PG, Laros GS (Oct 1987). "The inflammatory effect of nucleus pulposus. A possible element in the pathogenesis of low-back pain". Spine. 12 (8): 760–4. doi:10.1097/00007632-198710000-00009. PMID 2961088. S2CID 22589442.

- Takahashi H, Suguro T, Okazima Y, Motegi M, Okada Y, Kakiuchi T (Jan 1996). "Inflammatory cytokines in the herniated disc of the lumbar spine". Spine. 21 (2): 218–24. doi:10.1097/00007632-199601150-00011. PMID 8720407. S2CID 10909087.

- Igarashi T, Kikuchi S, Shubayev V, Myers RR (Dec 2000). "2000 Volvo Award winner in basic science studies: Exogenous tumor necrosis factor-alpha mimics nucleus pulposus-induced neuropathology. Molecular, histologic, and behavioral comparisons in rats". Spine. 25 (23): 2975–80. doi:10.1097/00007632-200012010-00003. PMID 11145807. S2CID 45206575.

- Sommer C, Schäfers M (2004). "Mechanisms of neuropathic pain: the role of cytokines". Drug Discovery Today: Disease Mechanisms. 1 (4): 441–8. doi:10.1016/j.ddmec.2004.11.018.

- Igarashi A, Kikuchi S, Konno S, Olmarker K (Oct 2004). "Inflammatory cytokines released from the facet joint tissue in degenerative lumbar spinal disorders". Spine. 29 (19): 2091–5. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000141265.55411.30. PMID 15454697. S2CID 46717050.

- Sakuma Y, Ohtori S, Miyagi M, et al. (Aug 2007). "Up-regulation of p55 TNF alpha-receptor in dorsal root ganglia neurons following lumbar facet joint injury in rats". Eur Spine J. 16 (8): 1273–8. doi:10.1007/s00586-007-0365-3. PMC 2200776. PMID 17468886.

- Sekiguchi M, Kikuchi S, Myers RR (May 2004). "Experimental spinal stenosis: relationship between degree of cauda equina compression, neuropathology, and pain". Spine. 29 (10): 1105–11. doi:10.1097/00007632-200405150-00011. PMID 15131438. S2CID 41308365.

- Séguin CA, Pilliar RM, Roughley PJ, Kandel RA (Sep 2005). "Tumor necrosis factor-alpha modulates matrix production and catabolism in nucleus pulposus tissue". Spine. 30 (17): 1940–8. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000176188.40263.f9. PMID 16135983. S2CID 42449538.

- "Slipped discs: "they do not actually 'slip'..."". Emedicinehealth.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2011-12-19.

- "Prolapsed disc". Spine-inc.com. Archived from the original on 2012-01-02. Retrieved 2011-12-19.

- Ehealthmd.com FAQ: "...the entire disc does not 'slip' out of place." Archived 2010-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Burke, Gerald L. "Backache: From Occiput to Coccyx". MacDonald Publishing. Archived from the original on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- Waddell G, McCulloch JA, Kummel E, Venner RM (1980). "Nonorganic physical signs in low-back pain". Spine. 5 (2): 117–25. doi:10.1097/00007632-198003000-00005. PMID 6446157. S2CID 29441806.

- Rabin A, Gerszten PC, Karausky P, Bunker CH, Potter DM, Welch WC (2007). "The sensitivity of the seated straight-leg raise test compared with the supine straight-leg raise test in patients presenting with magnetic resonance imaging evidence of lumbar nerve root compression". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 88 (7): 840–3. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.04.016. PMID 17601462.

- van der Windt, Daniëlle AWM; Simons, Emmanuel; Riphagen, Ingrid I; Ammendolia, Carlo; Verhagen, Arianne P; Laslett, Mark; Devillé, Walter; Deyo, Rick A; Bouter, Lex M; de Vet, Henrica CW; Aertgeerts, Bert (2010-02-17). "Physical examination for lumbar radiculopathy due to disc herniation in patients with low-back pain". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD007431. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007431.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 20166095. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ^ Al Qaraghli, MI; De Jesus, O (2021), "article-24453", Lumbar Disc Herniation, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32809713, archived from the original on 2022-02-21, retrieved 2021-09-09

- Deftereos SN, et al. (April–June 2009). "Localisation of cervical spinal cord compression by TMS and MRI". Funct Neurol. 24 (2): 99–105. PMID 19775538.

- Chen R, Cros D, Curra A, et al. (March 2008). "The clinical diagnostic utility of transcranial magnetic stimulation: report of an IFCN committee". Clin Neurophysiol. 119 (3): 504–32. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2007.10.014. PMID 18063409. S2CID 8345397.

- Vroomen PC, de Krom MC, Knottnerus JA (Feb 2002). "Predicting the outcome of sciatica at short-term follow-up". Br J Gen Pract. 52 (475): 119–23. PMC 1314232. PMID 11887877.

- Pinto, RZ; Maher, CG; Ferreira, ML; Hancock, M; Oliveira, VC; McLachlan, AJ; Koes, B; Ferreira, PH (18 December 2012). "Epidural corticosteroid injections in the management of sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (12): 865–77. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00564. PMID 23362516. S2CID 21203011.

- Abbasi A, Malhotra G, Malanga G, Elovic EP, Kahn S (Sep 2007). "Complications of interlaminar cervical epidural steroid injections: a review of the literature". Spine. 32 (19): 2144–51. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e318145a360. PMID 17762818. S2CID 23087393.

- "Epidural Corticosteroid Injection: Drug Safety Communication - Risk of Rare But Serious Neurologic Problems". FDA. 2014. Archived from the original on April 6, 2017.

- Leininger B, Bronfort G, Evans R, Reiter T (2011). "Spinal manipulation or mobilization for radiculopathy: a systematic review". Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 22 (1): 105–25. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2010.11.002. PMID 21292148.

- Hahne AJ, Ford JJ, McMeeken JM (2010). "Conservative management of lumbar disc herniation with associated radiculopathy: a systematic review". Spine. 35 (11): E488–504. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181cc3f56. PMID 20421859. S2CID 19121111. Archived from the original on 2023-05-31. Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- Snelling N (2006). "Spinal manipulation in patients with disc herniation: A critical review of risk and benefit". International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine. 9 (3): 77–84. doi:10.1016/j.ijosm.2006.08.001. Archived from the original on 2014-03-18. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- Oliphant, D (2004). "Safety of Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Lumbar Disk Herniations: A Systematic Review and Risk Assessment". Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 27 (3): 197–210. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2003.12.023. PMID 15129202.

- Foreman, A. Croft, S. Whiplash Injuries The Cervical Acceleration/Deceleration Syndrome. Williams and Wilkins. 428 E. Preston Street. Baltimore, MD. 21202 p 469

- Nordhoff, L. Motor Vehicle Collision Injuries, Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Management. Aspen Publisher, Inc. Gaithersburg, MD 1996 p 94

- Haldeman, S. Principles and Practice of Chiropractic. Appleton & Lange, 25 Van Zant Str., East Norwalk, CT. 1992 p 565

- WHO guidelines on basic training and safety in chiropractic. "2.1 Absolute contraindications to spinal manipulative therapy", p. 21. Archived 2020-04-29 at the Wayback Machine WHO

- Daniel, Dwain M (2007). "Non-surgical spinal decompression therapy: does the scientific literature support efficacy claims made in the advertising media?". Chiropractic & Osteopathy. 15 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/1746-1340-15-7. PMC 1887522. PMID 17511872.

- Be Wary of Spinal Decompression Therapy with VAX-D or Similar Devices Archived 2019-06-20 at the Wayback Machine, Stephen Barrett

- ^ Manusov, EG (September 2012). "Surgical treatment of low back pain". Primary Care. 39 (3): 525–31. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2012.06.010. PMID 22958562.

- Book Chapter - Decision Making in Spinal Care - Chapter 61; Copyright 2013 by Thieme

- Rasouli, MR; Rahimi-Movaghar, V; Shokraneh, F; Moradi-Lakeh, M; Chou, R (Sep 4, 2014). "Minimally invasive discectomy versus microdiscectomy/open discectomy for symptomatic lumbar disc herniation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD010328. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010328.pub2. PMC 10961733. PMID 25184502. S2CID 25838265.

- Ahn, Yong; Choi, Gun; Lee, Sang-Ho (2016). "History of Lumbar Endoscopic Spinal Surgery and the Intradiskal Therapies". Advanced Concepts in Lumbar Degenerative Disk Disease. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 783–791. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-47756-4_53. ISBN 978-3-662-47755-7.

- Gibson, J. N. A.; Waddell, G. (2007-04-18). Gibson, JN Alastair (ed.). "Surgical interventions for lumbar disc prolapse". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (2): CD001350. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001350.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7028003. PMID 17443505.

- Oosterhuis, Teddy; Costa, Leonardo OP; Maher, Christopher G; de Vet, Henrica CW; van Tulder, Maurits W; Ostelo, Raymond WJG (2014-03-14). "Rehabilitation after lumbar disc surgery". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (3): CD003007. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003007.pub3. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 7138272. PMID 24627325.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Herniated nucleus pulposus Frequency

- Jacobs WC, Arts MP, van Tulder MW, et al. (November 2012). "Surgical techniques for sciatica due to herniated disc, a systematic review". Eur Spine J. 21 (11): 2232–51. doi:10.1007/s00586-012-2422-9. PMC 3481105. PMID 22814567.

- Marrone, Lisa (2008). Overcoming Back and Neck Pain. Harvest House. p. 37.

- Marrone, Lisa (2008). Overcoming Back and Neck Pain. Harvest House. p. 31.

- Leung VY, Chan D, Cheung KM (Aug 2006). "Regeneration of intervertebral disc by mesenchymal stem cells: potentials, limitations, and future direction". Eur Spine J. 15 (Suppl 3): S406–13. doi:10.1007/s00586-006-0183-z. PMC 2335386. PMID 16845553.

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Spinal disease | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deforming |

| ||||

| Spondylopathy |

| ||||

| Back pain | |||||

| Intervertebral disc disorder | |||||