| Native name: 出島 | |

|---|---|

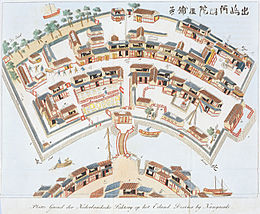

An imagined bird's-eye view of Dejima's layout and structures (copied from a woodblock print by Toshimaya Bunjiemon of 1780 and published in Isaac Titsingh's Bijzonderheden over Japan (1824/25) An imagined bird's-eye view of Dejima's layout and structures (copied from a woodblock print by Toshimaya Bunjiemon of 1780 and published in Isaac Titsingh's Bijzonderheden over Japan (1824/25) | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Nagasaki |

| Administration | |

| Japan | |

Dejima (Japanese: 出島, lit. 'exit island') or Deshima, in the 17th century also called Tsukishima (築島, lit. 'built island'), was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan, that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1858). For 220 years, it was the central conduit for foreign trade and cultural exchange with Japan during the isolationist Edo period (1600–1869), and the only Japanese territory open to Westerners.

Spanning 120 m × 75 m (390 ft × 250 ft) or 9,000 m (2.2 acres), Dejima was created in 1636 by digging a canal through a small peninsula and linking it to the mainland with a small bridge. The island was constructed by the Tokugawa shogunate, whose isolationist policies sought to preserve the existing sociopolitical order by forbidding outsiders from entering Japan while prohibiting most Japanese from leaving. Dejima housed European merchants and separated them from Japanese society while still facilitating lucrative trade with the West.

Following a rebellion by mostly Catholic converts, the Portuguese were expelled in 1639. The Dutch were moved to Dejima in 1641, under stricter control and scrutiny, and segregated from Japanese society. The open practice of Christianity was banned, and interactions between Dutch and Japanese traders were tightly regulated, with only a small number of foreign merchants being allowed to disembark in Dejima. Until the mid-19th century, the Dutch were the only Westerners with access to the Japanese markets. Dejima consequently played a key role in the Japanese movement of rangaku (蘭學, Dutch learning), an organized scholarly effort to learn the Dutch language in order to understand Western science, medicine, and technology.

After the 1854 Treaty of Kanagawa set a precedent for more fully opening Japan to foreign trade and diplomatic relations, the Dutch negotiated their own treaty in 1858, which ended Dejima's status as exclusive trading post, greatly reducing its importance. The island was eventually subsumed into Nagasaki city through land reclamation. In 1922, the "Dejima Dutch Trading Post" was designated a Japanese national historic site, and there are ongoing efforts in the 21st century to restore Dejima as an island.

History

In 1543, the history of direct contact between Japan and Europe began with the arrival of storm-blown Portuguese merchants on Tanegashima. Six years later the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier landed in Kagoshima. At first Portuguese traders were based in Hirado, but they moved in search of a better port. In 1570 daimyō Ōmura Sumitada converted to Catholicism (choosing Bartolomeu as his Christian name) and made a deal with the Portuguese to develop Nagasaki; soon the port was open for trade.

In 1580 Sumitada gave the jurisdiction of Nagasaki to the Jesuits, and the Portuguese obtained the de facto monopoly on the silk trade with China through Macau. The shōgun Iemitsu ordered the construction of the artificial island in 1634, to accommodate the Portuguese traders living in Nagasaki and prevent the propagation of their religion. This was one of the many edicts put forth by Iemitsu between 1633 and 1639 moderating contact between Japan and other countries. However, in response to the uprising of the predominantly Christian population in the Shimabara-Amakusa region, the Tokugawa government decided to expel the Portuguese in 1639.

Since 1609, the Dutch East India Company had run a trading post on the island of Hirado. The departure of the Portuguese left the Dutch employees of the "Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie" ("VOC") as the sole Westerners with trade access to Japan. For 33 years they were allowed to trade relatively freely. At its maximum, the Hirado trading post (平戸オランダ商館, Hirado Oranda Shōkan) covered a large area. In 1637 and 1639 stone warehouses were constructed within the ambit of this Hirado trading post. Christian-era year dates were used on the stonework of the new warehouses and these were used in 1640 as a pretext to demolish the buildings and relocate the trading post to Nagasaki.

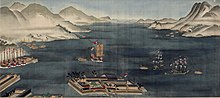

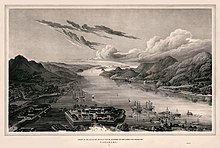

With the expulsion of the last Portuguese in 1639, Dejima became a failed commercial post and without the annual trading with Portuguese ships from Macau, the economy of Nagasaki suffered greatly. The Dutch were forced by government officials to move from Hirado to Dejima in Nagasaki. From 1641 on, only Chinese and Dutch ships were allowed to come to Japan, and Nagasaki harbor was the only one they were allowed to enter.

Organization

On the administrative level, the island of Dejima was part of the city of Nagasaki. The 25 local Japanese families who owned the land received an annual rent from the Dutch. Dejima was a small island, 120 metres (390 ft) by 75 metres (246 ft), linked to the mainland by a small bridge, guarded on both sides, and with a gate on the Dutch side. It contained houses for about twenty Dutchmen, warehouses, and accommodation for Japanese officials.

The Dutch were watched by several Japanese officials, gatekeepers, night watchmen, and a supervisor (乙名, otona) with about fifty subordinates. Numerous merchants supplied goods and catering, and about 150 interpreters (通詞, tsūji) served. They all had to be paid by the VOC. As the city of Nagasaki, Dejima was under the direct supervision of Edo through a governor (Nagasaki bugyō).

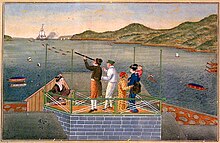

Every ship that arrived in Dejima was inspected. Its sails were held by the Japanese until they released the ship to leave. They confiscated religious books and weapons. Christian churches were banned on the island and the Dutch were not allowed to hold any religious services.

Despite the financial burden of maintaining the isolated outpost on Dejima, the trade with Japan was very profitable for the Dutch, initially yielding profits of 50% or more. Trade declined in the 18th century, as only two ships per year were allowed to dock at Dejima. After the bankruptcy of the East-India Company in 1795, the Dutch government took over the exchange with Japan. Times were especially hard when the Netherlands, then called the Batavian Republic, was under French Napoleonic rule. All ties with the homeland were severed at Dejima, and for a while, it was the only place in the world where the Dutch flag was flown.

The chief VOC trading post officer in Japan was called the Opperhoofd by the Dutch, or Kapitan (from Portuguese capitão) by the Japanese. This descriptive title did not change when the VOC went bankrupt and trade with Japan was continued by the Dutch Indies government at Batavia. According to the Sakoku rules of the Tokugawa shogunate, the VOC had to transfer and replace the opperhoofd every year with a new one. And each opperhoofd was expected to travel to Edo to offer tribute to the shogun.

Trade

Originally, the Dutch mainly traded in silk, cotton, and materia medica from China and India. Sugar became more important later. Deer pelts and shark skin were transported to Japan from Formosa, as well as books, scientific instruments and many other rarities from Europe. In return, the Dutch traders bought Japanese copper, silver, camphor, porcelain, lacquer ware, and rice.

To this was added the personal trade of VOC employees on Dejima, which was an important source of income for them and their Japanese counterparts. They sold more than 10,000 foreign books on various scientific subjects to the Japanese from the end of the 18th to the early 19th century. These became the basis of knowledge and a factor in the Rangaku movement, or Dutch studies.

Ships

In all, 606 Dutch ships arrived at Dejima during its two centuries of settlement, from 1641 to 1847.

- The first period, from 1641 to 1671, was rather free and saw an average of seven Dutch ships every year (12 sank during this period).

- From 1671 to 1715, about five Dutch ships were allowed to visit Dejima every year.

- From 1715, only two ships were permitted every year, which was reduced to one ship in 1790, and again increased to two ships in 1799.

- During the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), in which the Netherlands was occupied by (and a satellite of) France, Dutch ships abstained from sailing to Japan directly due to the possibility of being captured by Royal Navy ships. They relied on "neutral" American and Danish ships. The Netherlands was annexed by Napoleon Bonaparte (1810–1813), while Britain captured several Dutch colonial possessions and after the 1811 invasion of Java, Dejima was the only place in the world where the Dutch flag still flew, as ordered by commissioner Hendrik Doeff.

- In 1815 the Dutch East Indies was returned to the control of the Netherlands and regular Dutch trading traffic was reestablished.

Trade policy

For two hundred years, foreign merchants were generally not allowed to cross from Dejima to Nagasaki. Japanese civilians were likewise banned from entering Dejima, except interpreters, cooks, carpenters, clerks and yūjo ("women of pleasure") from the Maruyama teahouses. The yūjo were handpicked from 1642 by the Japanese, often against their will. From the 18th century, there were some exceptions to this rule, especially following Tokugawa Yoshimune's doctrine of promoting European practical sciences. A few Oranda-yuki ("those who stay with the Dutch") were allowed to stay for longer periods, but they had to report regularly to the Japanese guard post. Once a year the Europeans were allowed to attend the festivities at the Suwa-Shrine under escort. Sometimes physicians such as Engelbert Kaempfer, Carl Peter Thunberg, and Philipp Franz von Siebold were called to high-ranking Japanese patients with the permission of the authorities. Starting in the 18th century, Dejima became known throughout Japan as a center of medicine, military science, and astronomy. Many samurai traveled there for "Dutch studies" (Rangaku).

The Opperhoofd was treated like the representative of a tributary state, which meant that he had to pay a visit of homage to the shōgun in Edo. The Dutch delegation traveled to Edo yearly between 1660 and 1790, and once every four years thereafter. This prerogative was denied to the Chinese traders. The lengthy travel to the shogunal court broke the boredom of the Dutch stay, but it was a costly affair. Government officials told them in advance and in detail which (expensive) gifts were expected at the court, such as astrolabes, a pair of glasses, telescopes, globes, medical instruments, medical books, or exotic animals and tropical birds.

In return, the Dutch delegation received some gifts from the shōgun. On arrival in Edo, the Opperhoofd and his retinue, usually his scribe and the factory physician, had to wait in the Nagasakiya (長崎屋), their mandatory residence, until they were summoned at the court. During the reign of the somewhat eccentric shōgun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, they were expected to perform Dutch dances and songs for the amusement of the shōgun after their official audience, according to Engelbert Kaempfer. But they also used the opportunity of their stay of about two to three weeks in the capital to exchange knowledge with learned Japanese and, under escort, to visit the town.

Allegations published in the late 17th and early 18th century that Dutch traders were required by the Shogunate to renounce their Christian faith and undergo the test of treading on a fumi-e, an image of Jesus or Mary, are thought by modern scholars to be propaganda arising from the Anglo-Dutch Wars.

New introductions to Japan

- Photography, first lessons in photography given to Japanese in 1856 by the physician of the island, Dr. J. K. van den Broek.

- Badminton, a sport that originated in India, was introduced by the Dutch during the 18th century; it is mentioned in the Sayings of the Dutch.

- Billiards were introduced in Japan on Dejima in 1764; it is noted as "Ball striking table" (玉突の場) in the paintings of Kawahara Keiga (川原慶賀).

- Beer seems to have been introduced as imports during the period of isolation. The Dutch governor Doeff made his own beer in Nagasaki, following the disruption of trade during the Napoleonic Wars. Local production of beer started in Japan in 1880.

- Clover was introduced in Japan by the Dutch as packing material for fragile cargo. The Japanese called it "White packing herb" (シロツメクサ), in reference to its white flowers.

- Coffee was introduced in Japan by the Dutch under the name Moka and koffie. The latter name appears in 18th-century Japanese books. Siebold refers to Japanese coffee amateurs in Nagasaki around 1823.

- Japan's oldest piano was introduced by Siebold in 1823, and later given to a tradesperson in the name of Kumaya (熊谷). The piano is today on display in the Kumaya Art Museum (熊谷美術館), Hagi City.

- Paint (Tar), used for ships, was introduced by the Dutch. The original Dutch name (pek) was also adopted in Japanese, Penki (ペンキ).

- Cabbage and tomatoes were introduced in the 17th century by the Dutch.

- Chocolate was introduced between 1789 and 1801; it is mentioned as a drink in the pleasure houses of Maruyama.

- A diving bell with air supply by a pump was bought from Hugh Morton & Co. at Leith Docks near Edinburgh in 1834.

Nagasaki Naval Training Center

Following the forced opening of Japan by US Navy Commodore Perry in 1854, the Bakufu suddenly increased its interactions with Dejima in an effort to build up knowledge of Western shipping methods. The Nagasaki Naval Training Center (長崎海軍伝習所, Nagasaki Kaigun Denshūsho), a naval training institute, was established in 1855 by the government of the shōgun at the entrance of Dejima, to enable maximum interaction with Dutch naval know-how. The center was equipped with Japan's first steamship, the Kankō Maru, given by the government of the Netherlands the same year. The future Admiral Enomoto Takeaki was one of the students of the Training Center.

Reconstruction

The Dutch East India Company's trading post at Dejima was abolished when Japan concluded the Treaty of Kanagawa with the United States in 1858. This ended Dejima's role as Japan's only window on the Western world during the era of national isolation. Since then, the island was expanded by reclaimed land and merged into Nagasaki. Extensive redesigning of Nagasaki Harbor in 1904 obscured its original location. The original footprint of Dejima Island has been marked by rivets; but as restoration progresses, the ambit of the island will be easier to see at a glance.

Dejima today is a work in progress. The island was designated a national historic site in 1922, but further steps were slow to follow. Restoration work was started in 1953, but that project languished. In 1996, restoration of Dejima began with plans for reconstructing 25 buildings in their early 19th-century state. To better display Dejima's fan-shaped form, the project anticipated rebuilding only parts of the surrounding embankment wall that had once enclosed the island. Buildings that remained from the Meiji period were to be used.

In 2000, five buildings, including the Deputy Factor's Quarters, were completed and opened to the public. In the spring of 2006, the finishing touches were put on the Chief Factor's Residence, the Japanese Officials' Office, the Head Clerk's Quarters, the No. 3 Warehouse, and the Sea Gate. In total, some ten buildings throughout the area have been restored.

In 2017, six new buildings, as well as the Omotemon Bridge (the old bridge to the mainland), were restored. The bridge was officially opened in attendance of members of the Japanese and Dutch royal families.

Long-term planning intends that Dejima will again be surrounded by water on all four sides; its characteristic fan-shaped form and all of its embankment walls will be fully restored. This long-term plan will include large-scale urban redevelopment in the area. To make Dejima an island again will require rerouting the Nakashima River and moving a part of Route 499.

Chronology

- 1550: Portuguese ships visit Hirado.

- 1561: Following the murder of foreigners in the area of the Hirado clan, the Portuguese began to look for other ports to trade.

- 1570: Christian daimyō Ōmura Sumitada make a deal with the Portuguese to develop Nagasaki, six town blocks are built.

- 1571: Nagasaki Harbor is opened for trade, the first Portuguese ships enter.

- 1580: Ōmura Sumitada cedes jurisdiction over Nagasaki and Mogi to the Jesuits.

- 1588: Toyotomi Hideyoshi exerts direct control over Nagasaki, Mogi, and Urakami from the Jesuits.

- 1609: The Dutch East India Company opens a factory in Hirado. It closes in 1641 when it is moved to Dejima.

- 1612: Japan's feudal government decrees that Christian proselytizing on Bakufu lands is forbidden.

- 1616: All trade with foreigners except that with China is confined to Hirado and Nagasaki.

- 1634: The construction of Dejima begins.

- 1636: Dejima is completed; the Portuguese are interned on Dejima (Fourth National Isolation Edict).

- 1638: Shimabara Rebellion of Christian peasants is repressed with Dutch support, Christianity in Japan is repressed.

- 1639: Portuguese ships are prohibited from entering Japan. Consequently, the Portuguese are banished from Dejima.

- 1641: The Dutch East India Company Trading Post in Hirado is moved to Nagasaki.

- 1649: German surgeon Caspar Schamberger comes to Japan. Beginning of a lasting interest in Western style medicine.

- 1662: A shop is opened on Dejima to sell Imari porcelain.

- 1673: The English ship Return enters Nagasaki, but the shogunate refuses its request for trade.

- 1678: A bridge connecting Dejima with the shore is replaced with a stone bridge.

- 1690: German physician Engelbert Kaempfer comes to Dejima.

- 1696: Warehouses for secondary cargo reach completion on Dejima.

- 1698: The Nagasaki Kaisho (trade association) is founded.

- 1699: The Sea Gate is built at Dejima.

- 1707: Water pipes are installed on Dejima.

- 1775: Carl Thunberg starts his term as physician on Dejima.

- 1779: Surgeon Isaac Titsingh arrives for his first tour of duty as "Opperhoofd".

- 1798: Many buildings, including the Chief Factor's Residence, are destroyed by the Great Kansei Fire of Dejima.

- 1804: Russian Ambassador Nikolai Rezanov visits Nagasaki to request an exchange of trade between Japan and Imperial Russia.

- 1808: The Phaeton Incident occurs.

- 1823: German physician Philipp Franz von Siebold posted to Dejima.

Trading post chiefs (Opperhoofden)

Main article: VOC opperhoofden in JapanOpperhoofd is a Dutch word (plural opperhoofden) which literally means 'supreme head'. The Japanese used to call the trading post chiefs kapitan which is derived from Portuguese capitão (cf. Latin caput, head). In its historical usage, the word is a gubernatorial title, comparable to the English Chief factor, for the chief executive officer of a Dutch factory in the sense of trading post, as led by a Factor, i.e. agent.

Notable opperhoofden at Hirado

- François Caron: 03.02.1639 – 13.02.1641

Notable opperhoofden at Dejima

- François Caron: 03.02.1639 – 13.02.1641

- Zacharias Wagenaer : 01.11.1656 – 27.10.1657

- Zacharias Wagenaer : 22.10.1658 – 04.11.1659

- Andreas Cleyer : 20.10.1682 -08.11.1683

- Andreas Cleyer: 17.10.1685 – 05.11.1686

- Hendrik Godfried Duurkoop: 23.11.1776 – 11.11.1777

- Isaac Titsingh: 29.11.1779 – 05.11.1780

- Isaac Titsingh: 24.11.1781 – 26.10.1783

- Isaac Titsingh: _.08.1784 – 30.11.1784

- Hendrik Doeff: 14.11.1803 – 06.12.1817

- Jan Cock Blomhoff: 06.12.1817 – 20.11.1823

- Janus Henricus Donker Curtius: 02.11.1852 – 28.02.1860

Gallery

-

Dutchmen with Keiseis (Courtesans), Nagasaki, ca. 1800

Dutchmen with Keiseis (Courtesans), Nagasaki, ca. 1800

-

Hendrik Doeff and a Balinese servant in Dejima, Japanese painting, ca. early 19th century

Hendrik Doeff and a Balinese servant in Dejima, Japanese painting, ca. early 19th century

-

A monument erected in Dejima by Siebold to honor Kaempfer and Thunberg

A monument erected in Dejima by Siebold to honor Kaempfer and Thunberg

-

A scale model of a Dutch trading post on display in Dejima (1995)

A scale model of a Dutch trading post on display in Dejima (1995)

See also

- Dutch missions to Edo

- Japan–Netherlands relations

- Nanban trade

- List of Jesuit sites

- Sakoku

- The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet – Historical novel set in Dejima

- Nagasaki foreign settlement

- Thirteen Factories, a former area of Guangzhou, China, where the first foreign trade was allowed in the 18th century since the hai jin (海禁) ban on maritime activities.

- Baan Hollanda – Site of former Dutch settlement in Ayutthaya (Thailand), now a museum

- Ghost in the Shell: S.A.C. 2nd GIG – Much of the action centers on refugees who are settled on the island and eventually try to declare independence

- Nagasaki saikenzu. Hayashi Jiza'emon, publisher. 1830.

Notes

- Also romanised in older documents as Decima, Decuma, Desjima, Dezima, Disma or Disima.

- In the context of Commodore Perry's "opening" of Japan in 1853, American naval expedition planners incorporated reference material written by men whose published accounts of Japan were based on first-hand experience. J. W. Spaulding brought with him books by Japanologists Engelbert Kaempfer, Carl Peter Thunberg, and Isaac Titsingh.

References

- "Dejima Nagasaki | JapanVisitor Japan Travel Guide". www.japanvisitor.com. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- Goss, Rob. "The Wild West Outpost of Japan's Isolationist Era". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- "rangaku | Japanese history | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- Laver, Michael S. (2011). The Sakoku Edicts and the Politics of Tokugawa Hegemony. Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1-60497-738-7.

- Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibition catalog. (2000). "A Very Unique Collection of Historical Significance: The Kapitan (the Dutch Chief) Collection from the Edo Period – The Dutch Fascination with Japan", p. 206.

- Dutch Trading Post Heritage Network, 2021.Hirado.

- Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibition catalog, p. 207.

- Ken Vos – The article "Dejima als venster en doorgeefluik" in the catalog (Brussels, 5 October 1989 – 16 December 1989) of the exhibition Europalia 1989: "Oranda: De Nederlanden in Japan (1600–1868)"

- Goss, Rob (May 13, 2022). "The Wild West Outpost of Japan's Isolationist Era". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- Screech, T. (2006). Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779–1822, p. 73.

- Gardiner, Anne Barbeau (Summer 1991). "Swift on the Dutch East India Merchants: The Context of 1672-73 War Literature". Huntington Library Quarterly. 54 (3): 234–252. doi:10.2307/3817708. JSTOR 3817708. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibition catalog, p. 47.

- "Opening ceremony Omotemon-bashi Bridge". hollandkyushu.com. Archived from the original on 2018-01-25. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

Bibliography

- Blomhoff, J. C. (2000). The Court Journey to the Shogun of Japan: From a Private Account by Jan Cock Blomhoff. Amsterdam

- Blussé, L. et al., eds. (1995–2001) The Deshima [sic] Dagregisters: Their Original Tables of Content. Leiden.

- Blussé, L. et al., eds. (2004). The Deshima Diaries Marginalia 1740–1800. Tokyo.

- Boxer. C. R. (1950). Jan Compagnie in Japan, 1600–1850: An Essay on the Cultural, Artistic, and Scientific Influence Exercised by the Hollanders in Japan from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Centuries. Den Haag.

- Caron, François. (1671). A True Description of the Mighty Kingdoms of Japan and Siam. London.

- Doeff, Hendrik. (1633). Herinneringen uit Japan. Amsterdam.

- Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibition catalog. (2000). A Very Unique Collection of Historical Significance: The Kapitan (the Dutch Chief) Collection from the Edo Period—The Dutch Fascination with Japan. Catalog of "400th Anniversary Exhibition Regarding Relations between Japan and the Netherlands", a joint project of the Edo-Tokyo Museum, the City of Nagasaki, the National Museum of Ethnology, the National Natuurhistorisch Museum and the National Herbarium of the Netherlands in Leiden, Netherlands. Tokyo.

- Leguin, F. (2002). Isaac Titsingh (1745–1812): Een passie voor Japan, leven en werk van de grondlegger van de Europese Japanologie. Leiden.

- Mitchell, David (2010). The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet. London.

- Nederland's Patriciaat, Vol. 13 (1923). Den Haag.

- Screech, Timon. (2006). Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779–1822. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-7007-1720-X

- Siebold, P.F.v. (1897). Nippon. Würzburg / Leipzig.Click link for full text in modern German

- Titsingh, I. (1820). Mémoires et Anecdotes sur la Dynastie régnante des Djogouns, Souverains du Japon. Paris: Nepveau.

- Titsingh, I. (1822). Illustrations of Japan; consisting of Private Memoirs and Anecdotes of the reigning dynasty of The Djogouns, or Sovereigns of Japan. London: Ackerman.

External links

- Dejima official website(Japanese & English)

- Trading-post chiefs, surgeons, physicians and other employees at the VOC factories Hirado and Dejima

- Hendrick Hamel in Japan: Deshima, layout and building placement Archived 2016-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

- WorldStatesmen – Japan

- New York Public Library Digital Gallery: Engelbert Kaempfer's map of Nagasaki harbor, 1727 Deshima location

| Portuguese Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dutch colonial empire | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

32°44′37″N 129°52′23″E / 32.74352°N 129.87302°E / 32.74352; 129.87302

Categories: