United States historic place

| Dismal Swamp Canal | |

| U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

| U.S. Historic district | |

| Virginia Landmarks Register | |

A sailboat on the Dismal Swamp Canal A sailboat on the Dismal Swamp Canal | |

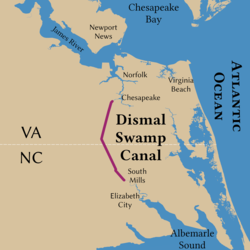

Path of the canal Path of the canal | |

| Location | Runs between Chesapeake, Virginia, and South Mills, North Carolina |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°33′24″N 76°22′50″W / 36.55667°N 76.38056°W / 36.55667; -76.38056 |

| Area | 1,203 acres (487 ha) |

| Built | 1793–1805 |

| Architect | Dismal Swamp Canal Co.; US Army Corps of Engineers |

| MPS | Dismal Swamp Canal and Associated Development, Southeast Virginia and Northeast North Carolina MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 88000528 |

| VLR No. | 131-0035 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 06, 1988 |

| Designated VLR | August 16, 1994 |

The Dismal Swamp Canal is a canal located along the eastern edge of the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia and North Carolina in the United States. Opened in 1805, it is the oldest continually operating man-made canal in the United States. It is part of the Intracoastal Waterway.

History

In the Colonial period, water transportation was the lifeblood of the North Carolina sounds region and the Tidewater areas of Virginia. The landlocked sounds were entirely dependent upon poor overland tracks or shipment along the treacherous Carolina coast to reach further markets through Norfolk, Virginia. In May 1763, George Washington made his first visit to the Great Dismal Swamp and suggested draining it and digging a north–south canal through it to connect the waters of the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia and Albemarle Sound in North Carolina. As the first president, Washington agreed with Virginia Governor Patrick Henry that canals were the easiest answer for an efficient means of internal transportation and urged their creation and improvement.

In 1784, the Dismal Swamp Canal Company was created. Work was started in 1793. The canal was dug completely by hand; most of the labor was done by slaves rented from nearby landowners. It took approximately 12 years of construction under highly unfavorable conditions to complete the 22-mile long waterway, which opened in 1805. At about the time the canal opened, the Dismal Swamp Hotel was built astride the state line on the west bank. It was a popular spot for lover's trysts as well as duels; the winner was rarely arrested as the dead man, as well as the crime, were in another state. As the state line split the main salon, the hotel was quite popular with gamblers who would simply move the game to the opposite side of the room with the arrival of the sheriff from the other jurisdiction. No trace of the hotel can be found today.

Tolls were charged for maintenance and improvements. In 1829, the channel was deepened. The waterway was an important route of commerce in the era before railroads, such as the Petersburg Railroad, and highways became major transportation modes.

American Civil War

During the American Civil War (1861–1865) the canal was in an important strategic position for Union and Confederate forces. In April, 1862, upon learning of rumors that the canal would be used to help the Confederate ironclad escape from Hampton Roads to the Albemarle Sound in North Carolina, Union General Ambrose E. Burnside sent General Jesse L. Reno from Roanoke Island to destroy the Culpepper Locks near South Mills on the Dismal Swamp Canal. Reno's 3,000 troops disembarked from their transports near Elizabeth City on April 18.

The Union troops advanced the following morning on an exhausting march toward South Mills where Confederate Colonel Ambrose R. Wright posted his 900 men to command the road to the town. Reno encountered Wright's position at noon. The Confederates' determined fighting continued for four hours until their artillery commander, Captain W. W. McComas, was killed. To avoid being flanked, Wright retired behind Joy's Creek, two miles away. General Reno did not pursue them because of his losses and his troops' exhaustion. That evening he heard a rumor that Confederate reinforcements were arriving from Norfolk and ordered a silent march back to the transports near Elizabeth City. The losses were estimated at 114 Union and 25 Confederate soldiers.

The Battle of South Mills was the only battle action near the canal. However, wartime activity left the canal in a terrible state of repair. The repairs and maintenance needed by the canal made travel difficult.

Post-war, 20th century

In 1892, Lake Drummond Canal and Water Company launched rehabilitation efforts and once again, a steady stream of vessels carrying lumber, shingles, farm products, and passengers made the canal a bustling interstate thoroughfare.

By the 1920s, improvements in other modes of transportation meant another downturn for the canal, and commercial traffic had subsided except for passenger vessels. In 1929 it was sold to the federal government for $500,000 (~$6.99 million in 2023). As recreational boating became popular in the mid-20th century, the canal became an important link to provide shelter from the brutal forces of the treacherous Atlantic Coast line off the Carolinas and the Virginia capes.

Current use

In modern times, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers operates and maintains the canal. The Dismal Swamp Canal is one of two inland routes connecting the Chesapeake Bay and the Albemarle Sound. About 2,000 recreational boaters transit the canal each year as they pass through the Intracoastal Waterway.

The canal was closed to boating traffic in October 2016 after Hurricane Matthew caused a flash flood in Chesapeake, Virginia. The runoff from this storm filled the canal with silt and sand, making it impassable. The necessary dredging for navigation on the canal was completed November 2017 to a depth of approximately five feet, and reopened for a short time before closing again, due to being inundated with duckweed. The duckweed clogs the intakes on power boats, quickly causing them to overheat. The Elizabeth River runs almost parallel to the canal, and was not affected by the 2016 flash flood, being much wider and much deeper than the canal. As of March 2018, the canal has been reopened by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The ICW has remained open during all of this via the Elizabeth River and the North Landing River.

The Virginia portion of the canal was located in Norfolk County, which today is the city of Chesapeake, where the northern portion of the canal at Deep Creek connects with the Southern Branch Elizabeth River.

The southern end of the canal leads to the Albemarle Sound. The Dismal Swamp Canal Visitor Center is the only visitor center in the continental U. S. greeting visitors by both a major highway and a historic waterway. It is located in Camden County, North Carolina, on scenic U.S. Highway 17 three miles south of the Virginia/North Carolina border.

The canal is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and has been designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark. The historic canal is now recognized as part of the Underground Railroad and along with the Great Dismal Swamp, is noted as a former sanctuary for runaway slaves seeking freedom.

The East Coast Greenway, a 3,000-mile long system of trails connecting Maine to Florida, runs along part of the Dismal Swamp Canal Trail.

Boaters visiting the swamp in the Fall need to be very conscious of the level of duckweed clogging the waterway, which can clog water intakes on power boat engines and systems.

See also

- Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge

- Lake Drummond

- Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal

- List of canals in the United States

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- Parramore, Thomas C. (2000). Norfolk: The First Four Centuries, p. 147. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-1988-6.

- Forrest, William S. (1858). Historical and Descriptive Sketches of Norfolk and Vicinity, p. 483. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston.

External links

- Great Dismal Swamp Canal megasite

- Dismal Swamp Canal Visitors Center

- Civil War Battlefield Guide; South Mills webpage

- US Army Corps of Engineers: Virtual Museum

- 36°23′20″N 76°17′09″W / 36.3888°N 76.2857°W / 36.3888; -76.2857 – Southern terminus

- 36°44′56″N 76°20′14″W / 36.7489°N 76.3371°W / 36.7489; -76.3371 – Northern terminus

- Canals on the National Register of Historic Places in Virginia

- Buildings and structures in Camden County, North Carolina

- Canals in Virginia

- Canals in North Carolina

- Canals on the National Register of Historic Places in North Carolina

- Intracoastal Waterway

- Virginia in the American Civil War

- North Carolina in the American Civil War

- Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks

- Transportation in Chesapeake, Virginia

- Tourist attractions in Chesapeake, Virginia

- Transportation in Camden County, North Carolina

- National Register of Historic Places in Chesapeake, Virginia

- Great Dismal Swamp

- Underground Railroad locations

- Canals opened in 1805

- National Register of Historic Places in Camden County, North Carolina

- 1805 establishments in Virginia

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in North Carolina

- Historic Albemarle Tour