"Chadburn" redirects here. For other uses, see Chadbourne.

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Engine order telegraph" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

An engine order telegraph or E.O.T., also referred to as a Chadburn, is a communications device used on a ship (or submarine) for the pilot on the bridge to order engineers in the engine room to power the vessel at a certain desired speed.

Construction

In its original form, from the 19th century until about 1950, the device usually consisted of a round dial about 9 inches (230 mm) in diameter with a knob at the center attached to one or more handles, and an indicator pointer on the face of the dial. There would also be a revolutions per minute (RPM) indicator, worked by a hand crank. Modern EOTs on vessels which still use them use electronic light and sound signals.

Operation

Traditional EOTs required a pilot wanting to change speed to "ring" the telegraph on the bridge, moving the handle to a different position on the dial. This would ring a bell in the engine room and move their pointer to the position on the dial selected by the bridge. The engineers hear the bell and move their handle to the same position to signal their acknowledgment of the order, and adjust the engine speed accordingly. Such an order is called a "bell"; for example, the order for a ship's maximum speed, flank speed, is called a "flank bell".

For urgent orders requiring rapid acceleration, the handle is moved three times so that the engine room bell is rung three times. This is called a "cavitate bell" because the rapid acceleration of the ship's propeller will cause the water around it to cavitate, causing a lot of noise and wear on the propellers. Such noise is undesirable during conflicts because it can give away a vessel's position.

Compared to remote control throttle

On most modern vessels with direct combustion engines or electric propulsors, the main control handle on the bridge acts as a direct throttle with no intervening engine room personnel. As such, it is regarded under the rules of marine classification societies as a remote control device rather than an EOT, though it is still often referred to by the traditional name. This is somewhat confusing, as the classification society rules for merchant ships still in fact require an EOT to be provided, to allow orders to be transmitted to the local control position in the engine room in the event that the remote control system should fail. The EOT is required to be electrically isolated from the remote control system. However, it may be mechanically linked to the main control handle, allowing telegraph orders to be given using the same user interface as for remote control orders. Traditional EOTs (though in a more modern form) can still be found on all nuclear powered ships and submarines as they still require an engineering crew member to operate the throttles for the steam turbines that drive the propellers. EOTs can also be found on older vessels that lack remote control technology, particularly those with conventional steam engines.

Remote control systems on modern ships usually have a control transfer system allowing control to be transferred between locations. Remote control is usually possible from two locations: the bridge and the Engine Control Room (ECR). Some ships lack a remote control handle in the ECR. When in bridge control mode, the bridge handle directly controls the engine set point. When in Engine Control Room mode the bridge handle sends a telegraph signal to the ECR and the ECR handle controls the set point of the control system. In local control, the remote control system is inactive and the bridge handle sends a telegraph signal to the local control position and the engine is operated by its manual controls in the engine room.

Order transmission

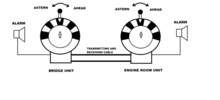

At least two telegraph units and alarms must be installed, one on the bridge and one in the engine room. The order is given by moving the bridge unit's handle to the desired position on the dial face. This sends an electrical signal to the EOT placed in the engine room whose pointer acquires a position according to the signal given from the bridge. An audible alarm sounds at both ends. Accordingly, the watch-keeping engineer acknowledges the order by moving the handle of the engine room EOT to the required position and takes necessary action. This sends an electrical signal to the bridge EOT unit, causing its pointer to acquire the respective position. The alarm stops ringing to acknowledge that the order has been carried out.

Typical dial positions

Many past ships have the following dial indications:

- Flank ahead (1940–present) (US only)

- Full ahead

- Half ahead

- Slow ahead

- Dead slow ahead

- Standby

- Stop

- Finished with main engines

- Dead slow astern

- Slow astern

- Half astern

- Full astern

- Emergency astern (1940–present)

Any orders could also be accompanied by an RPM order, giving the precise engine speed desired. Many modern ships have the following dial indications:

- Full ahead navigation (on notice to increase or reduce)

- Full ahead

- Half ahead

- Slow ahead

- Dead slow ahead

- Stop

- Dead slow astern

- Slow astern

- Half astern

- Full astern

"Finished with engines" and "standby" conveyed via separate control panel.

See also

References

- "The Chadburn Ships' Telegraph Society". Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- Halpern, Samuel (18 September 2007). "Speed and Revolutions". Encyclopedia Titanica. Retrieved 6 January 2013.