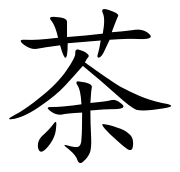

The etymology of the various words for tea reflects the history of transmission of tea drinking culture and trade from China to countries around the world. In this context, tea generally refers to the plant Camellia sinensis and/or the aromatic beverage prepared by pouring hot boiling water over the leaves. Nearly all of the words for tea worldwide originate from Chinese pronunciations of the word 茶, and they fall into three broad groups: te, cha and chai, present in English as tea, cha or char, and chai. The earliest of the three to enter English is cha, which came in the 1590s via the Portuguese, who traded in Macao and picked up the Cantonese pronunciation of the word. The more common tea form arrived in the 17th century via the Dutch, who acquired it either indirectly from teh in Malay, or directly from the tê pronunciation in Min Chinese. The third form chai (meaning "spiced tea") originated from a northern Chinese pronunciation of cha, which travelled overland to Central Asia and Persia where it picked up a Persian ending yi, and entered English via Hindustani in the 20th century.

The different regional pronunciations of the word in China are believed to have arisen from the same root, which diverged due to sound changes through the centuries. The written form of the Chinese word for tea was created in the mid-Tang dynasty by modifying the character 荼 pronounced tu, meaning a "bitter vegetable". Tu was used to refer to a variety of plants in ancient China, and acquired the additional meaning of "tea" by the Han dynasty. The Chinese word for tea was likely ultimately derived from the non-Sinitic languages of the botanical homeland of the tea plant in southwest China (or Burma), possibly from an archaic Austro-Asiatic root word *la, meaning "leaf".

Origins

The pronunciations of the words for "tea" worldwide mostly fall into the three broad groups: te, cha and chai. The exceptions are those in some languages from Southwest China and Myanmar, the botanical homeland of the tea plant. Examples are la (meaning tea purchased elsewhere) and miiem (wild tea gathered in the hills) from the Wa people of northeast Burma and southwest Yunnan, letpet in Burmese and meng in Lamet meaning "fermented tea leaves", tshuaj yej in Hmong language as well as miang in Thai ("fermented tea"). These languages belong to the Austro-Asiatic, Tibeto-Burman, Hmong-Mien, and Tai families of languages now found in South East Asia and southwest of China. Scholars have suggested that the Austro-Asiatic languages may be the ultimate source of the word tea, including the various Chinese words for tea such as tu, cha and ming. Cha for example may have been derived from an archaic Austro-Asiatic root word *la (Proto-Austroasiatic: *slaʔ, cognate with Proto-Vietic *s-laːʔ), meaning "leaf", while ming may be from the Mon–Khmer meng (fermented tea leaves). The Sinitic, Tibeto-Burman and Tai speakers who came into contact with the Austro-Asiatic speakers then borrowed their words for tea.

The Chinese character for tea is 茶, originally written with an extra horizontal stroke as 荼 (pronounced tu), and acquired its current form in the Tang dynasty first used in the eighth-century treatise on tea The Classic of Tea. The word tú 荼 appears in ancient Chinese texts such as Shijing signifying a kind of "bitter vegetable" (苦菜) and refers to various plants such as sow thistle, chicory, or smartweed, and also used to refer to tea during the Han dynasty. By the Northern Wei the word tu also appeared with a wood radical, meaning a tea tree. The word 茶 first introduced during the Tang dynasty refers exclusively to tea. It is pronounced differently in the different varieties of Chinese, such as chá in Mandarin, zo and dzo in Wu Chinese, and ta and te in Min Chinese. One suggestion is that the pronunciation of tu (荼) gave rise to tê; but historical phonologists believe that cha, te and dzo all arose from the same root with a reconstructed hypothetical pronunciation dra (dr- represents a single consonant for a retroflex d), which changed due to sound shift through the centuries. Other ancient words for tea include jia (檟, defined as "bitter tu" during the Han dynasty), she (蔎), ming (茗, meaning "fine, special tender tea") and chuan (荈), but ming is the only other word for tea that is still in common use.

Most Chinese languages, such as Mandarin, Gan and Hakka, pronounce it along the lines of cha, but Min varieties along the Southern coast of China pronounce it like teh. These two pronunciations have made their separate ways into other languages around the world:

- Te is from the Amoy tê of Hokkien dialect in southern Fujian. The ports of Xiamen (Amoy) and Quanzhou were once major points of contact with foreign traders. Western European traders such as the Dutch may have taken this pronunciation either directly from Fujian or Taiwan where they had established a port, or indirectly via Malay traders in Bantam, Java. The Dutch pronunciation of thee then spread to other countries in Western Europe. This pronunciation gives rise to English "tea" and similar words in other languages, and is the most common form worldwide.

- Cha originated from different parts of China. The "cha" pronunciation may come from the Cantonese pronunciation tsa around Guangzhou (Canton) and the ports of Hong Kong and Macau, also major points of contact, especially with the Portuguese, who spread it to India in the 16th century. The Korean and Japanese pronunciations of cha, however, came not from Cantonese; rather, they were borrowed into Korean and Japanese during earlier periods of Chinese history. Chai (Persian: چای chay) might have been derived from Northern Chinese pronunciation of chá, which passed overland to Central Asia and Persia, where it picked up the Persian ending -yi before passing on to Russian, Arabic, Turkish, etc. The chai pronunciation first entered English either via Russian or Arabic in the early 20th century, and then as a word for "spiced tea" via Hindi-Urdu which acquired the word under the influence of the Mughals.

English has all three forms: cha or char (both pronounced /ˈtʃɑː/), attested from the late 16th century; tea, from the 17th; and chai, from the 20th.

Languages in more intense contact with Chinese, Sinospheric languages like Korean, Vietnamese and Japanese, may have borrowed their pronunciations for tea at an earlier time and from a different variety of Chinese, in the so-called Sino-Xenic pronunciations. Although normally pronounced as cha (commonly with an honorific prefix o- as ocha) or occasionally as sa (as in sadô or kissaten), Japanese also retains the early but now uncommon pronunciations of ta and da. Similarly Korean also has ta in addition to cha, and Vietnamese trà in addition to chè. The different pronunciations for tea in Japanese arose from the different times the pronunciations were borrowed into the language: Sa is the Tō-on reading (唐音, literally Tang reading but in fact post Tang), 'ta' is the Kan-on (漢音) from the Middle Chinese spoken at the Tang dynasty court at Chang'an; which is still preserved in modern Min Dong da. Ja is the Go-on (呉音) reading from Wuyue region, and comes from the earlier Wu language centered at Nanjing, a place where the consonant was still voiced, as it is today in Hunanese za or Shanghainese zo. Zhuang language also features southern cha-type pronunciations.

Derivations from te and cha

The different words for tea fall into two main groups: "te-derived" (Min) and "cha-derived" (Cantonese and Mandarin). Most notably through the Silk Road; global regions with a history of land trade with central regions of Imperial China (such as North Asia, Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East) pronounce it along the lines of 'cha', whilst most global maritime regions with a history of sea trade with certain southeast regions of Imperial China (such as Europe), pronounce it like 'teh'.

The words that various languages use for "tea" reveal where those nations first acquired their tea and tea culture:

- Portuguese traders were the first Europeans to import the herb in large amounts. The Portuguese borrowed their word for tea (chá) from Cantonese in the 1550s via their trading posts in the south of China, especially Macau.

- In Central Asia, Mandarin cha developed into Persian chay, and this form spread with Central Asian trade and cultural influence.

- Russia (чай, chyai) encountered tea in Central Asia.

- The Dutch word for "tea" (thee) comes from Min Chinese. The Dutch may have borrowed their word for tea through trade directly from Fujian or Formosa, or from Malay traders in Java who had adopted the Min pronunciation as teh. The Dutch first imported tea around 1606 from Macao via Bantam, Java, and played a dominant role in the early European tea trade through the Dutch East India Company, influencing other European languages, including English, French (thé), Spanish (té), and German (Tee).

- The Dutch first introduced tea to England in 1644. By the 19th century, most British tea was purchased directly from merchants in Canton, whose population uses cha, the English however kept its Dutch-derived Min word for tea, although char is sometimes used colloquially to refer to the drink in British English (see below).

At times, a te form will follow a cha form, or vice versa, giving rise to both in one language, at times one an imported variant of the other:

- In North America, the word chai is used to refer almost exclusively to the Indian masala chai (spiced tea) beverage, in contrast to tea itself.

- The inverse pattern is seen in Moroccan Arabic where , shay means "generic, or black Middle Eastern tea" whereas atay refers particularly to Zhejiang or Fujian green tea with fresh mint leaves. The Moroccans are said to have acquired this taste for green tea—unique in the Arab world— from British exports in the 19th century (see Moroccan tea culture).

- The colloquial Greek word for tea is tsáï, from Slavic chai. Its formal equivalent, used in earlier centuries, is téïon, from tê.

- The Polish word for a tea-kettle is czajnik, which comes from the Russian word Чай (pronounced chai). However, tea in Polish is herbata, which, as well as Lithuanian arbata, was derived from the Dutch herba thee, although a minority believes that it was derived Latin herba thea, meaning "tea herb."

- The normal word for tea in Finnish is tee, which is a Swedish loan. However, it is often colloquially referred to, especially in Eastern Finland and in Helsinki, as tsai, tsaiju, saiju or saikka, which is cognate to the Russian word chai. The latter word refers always to black tea, while green tea is always tee.

- In Ireland, or at least in Dublin, the term cha is sometimes used for "tea," as is pre-vowel-shift pronunciation "tay" (from which the Irish Gaelic word tae is derived). Char was a common slang term for tea throughout British Empire and Commonwealth military forces in the 19th and 20th centuries, crossing over into civilian usage.

- The British slang word "char" for "tea" arose from its Cantonese Chinese pronunciation "cha" with its spelling affected by the fact that ar is a more common way of representing the phoneme /ɑː/ in British English.

- In Myanmar, the word of normal tea is "laat-paat-ray","လက်ဖက်ရည်". Burma called "laat-paat" for Camellia sinensis and "ray" stand for solution or juice.

Derivatives of te

| Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afrikaans | tee | Armenian | թեյ | Basque | tea | Belarusian | гарба́та (harbáta)(1) | Berber | ⵜⵢ, atay |

| Catalan | te | Kashubian | (h)arbata(1) | Czech | té or thé(2) | Danish | te | Dutch | thee |

| English | tea | Esperanto | teo | Estonian | tee | Faroese | te | Finnish | tee |

| French | thé | West Frisian | tee | Galician | té | German | Tee | Greek | τέϊον téïon |

| Hebrew | תה, te | Hungarian | tea | Icelandic | te | Irish | tae | Italian | tè |

| Javanese | tèh | Kannada | ಟೀಸೊಪ್ಪು ṭīsoppu | Khmer | តែ tae | (scientific) Latin | thea | Latvian | tēja |

| Leonese | té | Limburgish | tiè | Lithuanian | arbata(1) | Low Saxon | Tee or Tei | Malay (including Malaysian and Indonesian standards) | teh |

| Malayalam | തേയില tēyila | Maltese | tè | Norwegian | te | Occitan | tè | Polish | herbata(1) |

| Scots | tea ~ | Scottish Gaelic | tì, teatha | Sinhalese | tē තේ | Spanish | té | Sundanese | entèh |

| Swedish | te | Tamil | தேநீர் tēnīr (3) | Telugu | తేనీరు tēnīr (4) | Western Ukrainian | герба́та (herbáta)(1) | Welsh | te |

Notes:

- from Latin herba thea, found in Polish, Western Ukrainian, Lithuanian, Belarusian and Kashubian

- té or thé, but this term is considered archaic and is a literary expression; since roughly the beginning of the 20th century, čaj is used for 'tea' in Czech; see the following table

- nīr means water; tēyilai means "tea leaf" (ilai "leaf")

- nīru means water; ṭīyāku means "tea leaf" (āku = leaf in Telugu)

Derivatives of cha

| Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assamese | চাহ sah | Bengali | চা cha (sa in Eastern regions) | Cebuano | tsá | Chinese | 茶 Chá | English | cha or char |

| Gujarati | ચા chā | Japanese | 茶, ちゃ cha(1) | Kannada | ಚಹಾ chahā | Kapampangan | cha | Khasi | sha |

| cha | چاہ ਚਾਹ chá | Korean | 차 cha(1) | Kurdish | ça | Lao | ຊາ /saː˦˥/ | ||

| Marathi | चहा chahā | Oḍiā | ଚା' cha'a | Persian | چای chā | Portuguese | chá | Sindhi | chahen چانهه |

| Somali | shaah | Tagalog | tsaá | Thai | ชา /t͡ɕʰaː˧/ | Tibetan | ཇ་ ja | Vietnamese | trà and chè(2) |

Notes:

- The main pronunciations of 茶 in Korea and Japan are 차 cha and ちゃ cha, respectively. (Japanese ocha (おちゃ) is honorific.) These are connected with the pronunciations at the capitals of the Song and Ming dynasties.

- Trà and chè are variant pronunciations of 茶; the latter is a Northern Vietnam dialect word and is used to describe both the tea leaf and nước chè tươi, a drink made from freshly boiled raw tea leaves.

Derivatives of chai

| Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albanian | çaj | Amharic | ሻይ shay | Arabic | شاي shāy | Assyrian Neo-Aramaic | ܟ݈ܐܝ chai | Armenian | թեյ tey |

| Azerbaijani | çay | Bosnian | čaj | Bulgarian | чай chai | Chechen | чай chay | Croatian | čaj |

| Czech | čaj | English | chai | Finnish dialectal | tsai, tsaiju, saiju or saikka | Georgian | ჩაი chai | Greek | τσάι tsái |

| Hindi | चाय chāy | Kazakh | шай shai | Kyrgyz | чай chai | Kinyarwanda | icyayi | Judaeo-Spanish | צ'יי chai |

| Macedonian | чај čaj | Malayalam | ചായ chaaya | Mongolian | цай tsai | Nepali | chiyā चिया | Pashto | چای chay |

| Persian | چای chāī (1) | Romanian | ceai | Russian | чай chay | Serbian | чај čaj | Slovak | čaj |

| Slovene | čaj | Swahili | chai | Tajik | чой choy | Tatar | чәй çäy | Tlingit | cháayu |

| Turkish | çay | Turkmen | çaý | Ukrainian | чай chai | Urdu | چائے chai | Uzbek | choy |

Notes:

- Derived from the earlier pronunciation چا cha.

Others

| Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese | だ da, た ta(1) | Korean | 다 da [ta](1) | Hmong | tshuaj yej |

| Thai | miang(3) | Burmese | လက်ဖက် lahpet [ləpʰɛʔ](2) | Tai | la |

| Lamet | meng | Wa | la, miiem | Palaung | miem |

| Lahu | la | Lisu | la ja | Akha | lor bor |

| Kachin | hpalap | Karen | hla | Mon | la pek |

| Yi (Lolo) | la | Nusu | la ja | Hani | la be |

| Pa'O | la | Kayah | le | Naxi | le |

| Bai | gu | She | ku | Waxiang | khu |

- These are alternative Sino-xenic pronunciations, borrowed from Middle Chinese. Note that cha is the common pronunciation of "tea" in Japanese and Korean.

- Umbrella term for tea, including fermented tea leaves eaten as a meal

- Fermented tea

References

- Mair & Hoh 2009, pp. 262–264.

- ^ "tea". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Mair & Hoh 2009, p. 262.

- ^ Mair & Hoh 2009, pp. 264–265.

- Mair & Hoh 2009, p. 266.

- Mair & Hoh 2009, pp. 265–267.

- Albert E. Dien (2007). Six Dynasties Civilization. Yale University Press. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-300-07404-8.

- Bret Hinsch (2011). The ultimate guide to Chinese tea. Bret Hinsch. ISBN 978-974-480-129-6.

- Nicola Salter (2013). Hot Water for Tea: An inspired collection of tea remedies and aromatic elixirs for your mind and body, beauty and soul. ArchwayPublishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-60693-247-6.

- Benn 2015, p. 22.

- ^ Mair & Hoh 2009, p. 265.

- Peter T. Daniels, ed. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- "「茶」的字形與音韻變遷(提要)". Archived from the original on 29 September 2010.

- Keekok Lee (2008). Warp and Weft, Chinese Language and Culture. Eloquent Books. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-60693-247-6.

- "Why we call tea "cha" and "te"?", Hong Kong Museum of Tea Ware, archived from the original on 16 January 2018, retrieved 25 August 2014

- Dahl, Östen. "Feature/Chapter 138: Tea". The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Max Planck Digital Library. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- ^ Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado; Anthony Xavier Soares (June 1988). Portuguese Vocables in Asiatic Languages: From the Portuguese Original of Monsignor Sebastiao Rodolfo Dalgado. Vol. 1. South Asia Books. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-81-206-0413-1.

- ^ Mair & Hoh 2009, p. 263.

- "Chai". American Heritage Dictionary. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014.

Chai: A beverage made from spiced black tea, honey, and milk. ETYMOLOGY: Ultimately from Chinese (Mandarin) chá.

- "chai". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- "char". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 26 September 2016.

- "tea". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 18 March 2024.

- "chai". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 16 March 2024.

- Mair & Hoh 2009, p. 264.

- "Cultural Selection: The Diffusion of Tea and Tea Culture along the Silk Roads | Silk Roads Programme". en.unesco.org. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- Sonnad, Nikhil (11 January 2018). "Tea if by sea, cha if by land: Why the world only has two words for tea". Quartz. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Tea". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- Chrystal, Paul (15 October 2014). Tea: A Very British Beverage. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-3360-2.

Bibliography

- Benn, James A. (2015). Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-988-8208-73-9.

- Mair, Victor H.; Hoh, Erling (2009). The True History of Tea. Thames & Hudson. pp. 262–264. ISBN 978-0-500-25146-1.