Flow measurement is the quantification of bulk fluid movement. Flow can be measured using devices called flowmeters in various ways. The common types of flowmeters with industrial applications are listed below:

- Obstruction type (differential pressure or variable area)

- Inferential (turbine type)

- Electromagnetic

- Positive-displacement flowmeters, which accumulate a fixed volume of fluid and then count the number of times the volume is filled to measure flow.

- Fluid dynamic (vortex shedding)

- Anemometer

- Ultrasonic flow meter

- Mass flow meter (Coriolis force).

Flow measurement methods other than positive-displacement flowmeters rely on forces produced by the flowing stream as it overcomes a known constriction, to indirectly calculate flow. Flow may be measured by measuring the velocity of fluid over a known area. For very large flows, tracer methods may be used to deduce the flow rate from the change in concentration of a dye or radioisotope.

Kinds and units of measurement

Both gas and liquid flow can be measured in physical quantities of kind volumetric flow rate or mass flow rates, with respective SI units such as cubic meters per second or kilograms per second, respectively. These measurements are related by the material's density. The density of a liquid is almost independent of conditions. This is not the case for gases, the densities of which depend greatly upon pressure, temperature and to a lesser extent, composition.

When gases or liquids are transferred for their energy content, as in the sale of natural gas, the flow rate may also be expressed in terms of energy flow, such as gigajoule per hour or BTU per day. The energy flow rate is the volumetric flow rate multiplied by the energy content per unit volume or mass flow rate multiplied by the energy content per unit mass. Energy flow rate is usually derived from mass or volumetric flow rate by the use of a flow computer.

In engineering contexts, the volumetric flow rate is usually given the symbol , and the mass flow rate, the symbol .

For a fluid having density , mass and volumetric flow rates may be related by .

Gas

Gases are compressible and change volume when placed under pressure, are heated or are cooled. A volume of gas under one set of pressure and temperature conditions is not equivalent to the same gas under different conditions. References will be made to "actual" flow rate through a meter and "standard" or "base" flow rate through a meter with units such as acm/h (actual cubic meters per hour), sm/sec (standard cubic meters per second), kscm/h (thousand standard cubic meters per hour), LFM (linear feet per minute), or MMSCFD (million standard cubic feet per day).

Gas mass flow rate can be directly measured, independent of pressure and temperature effects, with ultrasonic flow meters, thermal mass flowmeters, Coriolis mass flowmeters, or mass flow controllers.

Liquid

For liquids, various units are used depending upon the application and industry, but might include gallons (U.S. or imperial) per minute, liters per second, liters per m per hour, bushels per minute or, when describing river flows, cumecs (cubic meters per second) or acre-feet per day. In oceanography a common unit to measure volume transport (volume of water transported by a current for example) is a sverdrup (Sv) equivalent to 10 m/s.

Primary flow element

A primary flow element is a device inserted into the flowing fluid that produces a physical property that can be accurately related to flow. For example, an orifice plate produces a pressure drop that is a function of the square of the volume rate of flow through the orifice. A vortex meter primary flow element produces a series of oscillations of pressure. Generally, the physical property generated by the primary flow element is more convenient to measure than the flow itself. The properties of the primary flow element, and the fidelity of the practical installation to the assumptions made in calibration, are critical factors in the accuracy of the flow measurement.

Mechanical flowmeters

A positive displacement meter may be compared to a bucket and a stopwatch. The stopwatch is started when the flow starts and stopped when the bucket reaches its limit. The volume divided by the time gives the flow rate. For continuous measurements, we need a system of continually filling and emptying buckets to divide the flow without letting it out of the pipe. These continuously forming and collapsing volumetric displacements may take the form of pistons reciprocating in cylinders, gear teeth mating against the internal wall of a meter or through a progressive cavity created by rotating oval gears or a helical screw.

Piston meter/rotary piston

Because they are used for domestic water measurement, piston meters, also known as rotary piston or semi-positive displacement meters, are the most common flow measurement devices in the UK and are used for almost all meter sizes up to and including 40 mm (1+1⁄2 in). The piston meter operates on the principle of a piston rotating within a chamber of known volume. For each rotation, an amount of water passes through the piston chamber. Through a gear mechanism and, sometimes, a magnetic drive, a needle dial and odometer type display are advanced.

Oval gear meter

An oval gear meter is a positive displacement meter that uses two or more oblong gears configured to rotate at right angles to one another, forming a T shape. Such a meter has two sides, which can be called A and B. No fluid passes through the center of the meter, where the teeth of the two gears always mesh. On one side of the meter (A), the teeth of the gears close off the fluid flow because the elongated gear on side A is protruding into the measurement chamber, while on the other side of the meter (B), a cavity holds a fixed volume of fluid in a measurement chamber. As the fluid pushes the gears, it rotates them, allowing the fluid in the measurement chamber on side B to be released into the outlet port. Meanwhile, fluid entering the inlet port will be driven into the measurement chamber of side A, which is now open. The teeth on side B will now close off the fluid from entering side B. This cycle continues as the gears rotate and fluid is metered through alternating measurement chambers. Permanent magnets in the rotating gears can transmit a signal to an electric reed switch or current transducer for flow measurement. Though claims for high performance are made, they are generally not as precise as the sliding vane design.

Gear meter

Gear meters differ from oval gear meters in that the measurement chambers are made up of the gaps between the teeth of the gears. These openings divide up the fluid stream and as the gears rotate away from the inlet port, the meter's inner wall closes off the chamber to hold the fixed amount of fluid. The outlet port is located in the area where the gears are coming back together. The fluid is forced out of the meter as the gear teeth mesh and reduce the available pockets to nearly zero volume.

Helical gear

Helical gear flowmeters get their name from the shape of their gears or rotors. These rotors resemble the shape of a helix, which is a spiral-shaped structure. As the fluid flows through the meter, it enters the compartments in the rotors, causing the rotors to rotate. The length of the rotor is sufficient that the inlet and outlet are always separated from each other thus blocking a free flow of liquid. The mating helical rotors create a progressive cavity which opens to admit fluid, seals itself off and then opens up to the downstream side to release the fluid. This happens in a continuous fashion and the flowrate is calculated from the speed of rotation.

Nutating disk meter

This is the most commonly used measurement system for measuring water supply in houses. The fluid, most commonly water, enters in one side of the meter and strikes the nutating disk, which is eccentrically mounted. The disk must then "wobble" or nutate about the vertical axis, since the bottom and the top of the disk remain in contact with the mounting chamber. A partition separates the inlet and outlet chambers. As the disk nutates, it gives direct indication of the volume of the liquid that has passed through the meter as volumetric flow is indicated by a gearing and register arrangement, which is connected to the disk. It is reliable for flow measurements within 1 percent.

Turbine flowmeter

The turbine flowmeter (better described as an axial turbine) translates the mechanical action of the turbine rotating in the liquid flow around an axis into a user-readable rate of flow (gpm, lpm, etc.). The turbine tends to have all the flow traveling around it.

The turbine wheel is set in the path of a fluid stream. The flowing fluid impinges on the turbine blades, imparting a force to the blade surface and setting the rotor in motion. When a steady rotation speed has been reached, the speed is proportional to fluid velocity.

Turbine flowmeters are used for the measurement of natural gas and liquid flow. Turbine meters are less accurate than displacement and jet meters at low flow rates, but the measuring element does not occupy or severely restrict the entire path of flow. The flow direction is generally straight through the meter, allowing for higher flow rates and less pressure loss than displacement-type meters. They are the meter of choice for large commercial users, fire protection, and as master meters for the water distribution system. Strainers are generally required to be installed in front of the meter to protect the measuring element from gravel or other debris that could enter the water distribution system. Turbine meters are generally available for 4 to 30 cm (1+1⁄2–12 in) or higher pipe sizes. Turbine meter bodies are commonly made of stainless steel, bronze, cast Iron, or ductile iron. Internal turbine elements can be plastic or non-corrosive metal alloys. They are accurate in normal working conditions but are greatly affected by the flow profile and fluid conditions.

Turbine flowmeters are commonly best suited for low viscosity, as large particulate can damage the rotor. When choosing a meter for an application that requires particulate flowing through the pipe, it is best to use a meter without moving parts such as a Magnetic flowmeters.

Fire meters are a specialized type of turbine meter with approvals for the high flow rates required in fire protection systems. They are often approved by Underwriters Laboratories (UL) or Factory Mutual (FM) or similar authorities for use in fire protection. Portable turbine meters may be temporarily installed to measure water used from a fire hydrant. The meters are normally made of aluminum to be lightweight, and are usually 7.5 cm (3 in) capacity. Water utilities often require them for measurement of water used in construction, pool filling, or where a permanent meter is not yet installed.

Woltman meter

The Woltman meter (invented by Reinhard Woltman in the 19th century) comprises a rotor with helical blades inserted axially in the flow, much like a ducted fan; it can be considered a type of turbine flowmeter. They are commonly referred to as helix meters, and are popular at larger sizes.

Single jet meter

A single jet meter consists of a simple impeller with radial vanes, impinged upon by a single jet. They are increasing in popularity in the UK at larger sizes and are commonplace in the EU.

Paddle wheel meter

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Paddle wheel flowmeters (also known as Pelton wheel sensors) consist of three primary components: the paddle wheel sensor, the pipe fitting and the display/controller. The paddle wheel sensor consists of a freely rotating wheel/impeller with embedded magnets which are perpendicular to the flow and will rotate when inserted in the flowing medium. As the magnets in the blades spin past the sensor, the paddle wheel meter generates a frequency and voltage signal which is proportional to the flow rate. The faster the flow the higher the frequency and the voltage output.

The paddle wheel meter is designed to be inserted into a pipe fitting, either 'in-line' or insertion style. Similarly to turbine meters, the paddle wheel meter requires a minimum run of straight pipe before and after the sensor.

Flow displays and controllers are used to receive the signal from the paddle wheel meter and convert it into actual flow rate or total flow values.

Multiple jet meter

A multiple jet or multijet meter is a velocity type meter which has an impeller which rotates horizontally on a vertical shaft. The impeller element is in a housing in which multiple inlet ports direct the fluid flow at the impeller causing it to rotate in a specific direction in proportion to the flow velocity. This meter works mechanically much like a single jet meter except that the ports direct the flow at the impeller equally from several points around the circumference of the element, not just one point; this minimizes uneven wear on the impeller and its shaft. Thus, these types of meters are recommended to be installed horizontally with its roller index pointing skywards.

Pelton wheel

The Pelton wheel turbine (better described as a radial turbine) translates the mechanical action of the Pelton wheel rotating in the liquid flow around an axis into a user-readable rate of flow (gpm, lpm, etc.). The Pelton wheel tends to have all the flow traveling around it with the inlet flow focused on the blades by a jet. The original Pelton wheels were used for the generation of power and consisted of a radial flow turbine with "reaction cups" which not only move with the force of the water on the face but return the flow in opposite direction using this change of fluid direction to further increase the efficiency of the turbine.

Current meter

Main article: Current meter

Flow through a large penstock such as used at a hydroelectric power plant can be measured by averaging the flow velocity over the entire area. Propeller-type current meters (similar to the purely mechanical Ekman current meter, but now with electronic data acquisition) can be traversed over the area of the penstock and velocities averaged to calculate total flow. This may be on the order of hundreds of cubic meters per second. The flow must be kept steady during the traverse of the current meters. Methods for testing hydroelectric turbines are given in IEC standard 41. Such flow measurements are often commercially important when testing the efficiency of large turbines.

Pressure-based meters

There are several types of flowmeter that rely on Bernoulli's principle. The pressure is measured either by using laminar plates, an orifice, a nozzle, or a Venturi tube to create an artificial constriction and then measure the pressure loss of fluids as they pass that constriction, or by measuring static and stagnation pressures to derive the dynamic pressure.

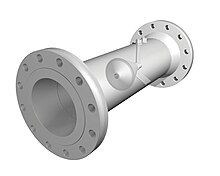

Venturi meter

A Venturi meter constricts the flow in some fashion, and pressure sensors measure the differential pressure before and within the constriction. This method is widely used to measure flow rate in the transmission of gas through pipelines, and has been used since Roman Empire times. The coefficient of discharge of Venturi meter ranges from 0.93 to 0.97. The first large-scale Venturi meters to measure liquid flows were developed by Clemens Herschel, who used them to measure small and large flows of water and wastewater beginning at the very end of the 19th century.

Orifice plate

An orifice plate is a plate with a hole through it, placed perpendicular to the flow; it constricts the flow, and measuring the pressure differential across the constriction gives the flow rate. It is basically a crude form of Venturi meter, but with higher energy losses. There are three type of orifice: concentric, eccentric, and segmental.

Dall tube

The Dall tube is a shortened version of a Venturi meter, with a lower pressure drop than an orifice plate. As with these flowmeters the flow rate in a Dall tube is determined by measuring the pressure drop caused by restriction in the conduit. The pressure differential is typically measured using diaphragm pressure transducers with digital readout. Since these meters have significantly lower permanent pressure losses than orifice meters, Dall tubes are widely used for measuring the flow rate of large pipeworks. Differential pressure produced by a Dall tube is higher than Venturi tube and nozzle, all of them having same throat diameters.

Pitot tube

Main article: Pitot tubeA pitot tube is used to measure fluid flow velocity. The tube is pointed into the flow and the difference between the stagnation pressure at the tip of the probe and the static pressure at its side is measured, yielding the dynamic pressure from which the fluid velocity is calculated using Bernoulli's equation. A volumetric rate of flow may be determined by measuring the velocity at different points in the flow and generating the velocity profile.

Averaging pitot tube

See also: AnnubarAveraging pitot tubes (also called impact probes) extend the theory of pitot tube to more than one dimension. A typical averaging pitot tube consists of three or more holes (depending on the type of probe) on the measuring tip arranged in a specific pattern. More holes allow the instrument to measure the direction of the flow velocity in addition to its magnitude (after appropriate calibration). Three holes arranged in a line allow the pressure probes to measure the velocity vector in two dimensions. Introduction of more holes, e.g. five holes arranged in a "plus" formation, allow measurement of the three-dimensional velocity vector.

Cone meters

Cone meters are a newer differential pressure metering device first launched in 1985 by McCrometer in Hemet, CA. The cone meter is a generic yet robust differential pressure (DP) meter that has shown to be resistant to effects of asymmetric and swirling flow. While working with the same basic principles as Venturi and orifice type DP meters, cone meters don't require the same upstream and downstream piping. The cone acts as a conditioning device as well as a differential pressure producer. Upstream requirements are between 0–5 diameters compared to up to 44 diameters for an orifice plate or 22 diameters for a Venturi. Because cone meters are generally of welded construction, it is recommended they are always calibrated prior to service. Inevitably heat effects of welding cause distortions and other effects that prevent tabular data on discharge coefficients with respect to line size, beta ratio and operating Reynolds numbers from being collected and published. Calibrated cone meters have an uncertainty up to ±0.5%. Un-calibrated cone meters have an uncertainty of ±5.0%

Linear resistance meters

Linear resistance meters, also called laminar flowmeters, measure very low flows at which the measured differential pressure is linearly proportional to the flow and to the fluid viscosity. Such flow is called viscous drag flow or laminar flow, as opposed to the turbulent flow measured by orifice plates, Venturis and other meters mentioned in this section, and is characterized by Reynolds numbers below 2000. The primary flow element may consist of a single long capillary tube, a bundle of such tubes, or a long porous plug; such low flows create small pressure differentials but longer flow elements create higher, more easily measured differentials. These flowmeters are particularly sensitive to temperature changes affecting the fluid viscosity and the diameter of the flow element, as can be seen in the governing Hagen–Poiseuille equation.

Variable-area flowmeters

A "variable area meter" measures fluid flow by allowing the cross sectional area of the device to vary in response to the flow, causing some measurable effect that indicates the rate. A rotameter is an example of a variable area meter, where a weighted "float" rises in a tapered tube as the flow rate increases; the float stops rising when area between float and tube is large enough that the weight of the float is balanced by the drag of fluid flow. A kind of rotameter used for medical gases is the Thorpe tube flowmeter. Floats are made in many different shapes, with spheres and spherical ellipses being the most common. Some are designed to spin visibly in the fluid stream to aid the user in determining whether the float is stuck or not. Rotameters are available for a wide range of liquids but are most commonly used with water or air. They can be made to reliably measure flow down to 1% accuracy.

Another type is a variable area orifice, where a spring-loaded tapered plunger is deflected by flow through an orifice. The displacement can be related to the flow rate.

Optical flowmeters

Not to be confused with Optical-flow sensors.Optical flowmeters use light to determine flow rate. Small particles which accompany natural and industrial gases pass through two laser beams focused a short distance apart in the flow path in a pipe by illuminating optics. Laser light is scattered when a particle crosses the first beam. The detecting optics collects scattered light on a photodetector, which then generates a pulse signal. As the same particle crosses the second beam, the detecting optics collect scattered light on a second photodetector, which converts the incoming light into a second electrical pulse. By measuring the time interval between these pulses, the gas velocity is calculated as where is the distance between the laser beams and is the time interval.

Laser-based optical flowmeters measure the actual speed of particles, a property which is not dependent on thermal conductivity of gases, variations in gas flow or composition of gases. The operating principle enables optical laser technology to deliver highly accurate flow data, even in challenging environments which may include high temperature, low flow rates, high pressure, high humidity, pipe vibration and acoustic noise.

Optical flowmeters are very stable with no moving parts and deliver a highly repeatable measurement over the life of the product. Because distance between the two laser sheets does not change, optical flowmeters do not require periodic calibration after their initial commissioning. Optical flowmeters require only one installation point, instead of the two installation points typically required by other types of meters. A single installation point is simpler, requires less maintenance and is less prone to errors.

Commercially available optical flowmeters are capable of measuring flow from 0.1 m/s to faster than 100 m/s (1000:1 turn down ratio) and have been demonstrated to be effective for the measurement of flare gases from oil wells and refineries, a contributor to atmospheric pollution.

Open-channel flow measurement

Open channel flow describes cases where flowing liquid has a top surface open to the air; the cross-section of the flow is only determined by the shape of the channel on the lower side, and is variable depending on the depth of liquid in the channel. Techniques appropriate for a fixed cross-section of flow in a pipe are not useful in open channels. Measuring flow in waterways is an important open-channel flow application; such installations are known as stream gauges.

Level to flow

The level of the water is measured at a designated point behind weir or in flume using various secondary devices (bubblers, ultrasonic, float, and differential pressure are common methods). This depth is converted to a flow rate according to a theoretical formula of the form where is the flow rate, is a constant, is the water level, and is an exponent which varies with the device used; or it is converted according to empirically derived level/flow data points (a "flow curve"). The flow rate can then be integrated over time into volumetric flow. Level to flow devices are commonly used to measure the flow of surface waters (springs, streams, and rivers), industrial discharges, and sewage. Of these, weirs are used on flow streams with low solids (typically surface waters), while flumes are used on flows containing low or high solids contents.

Area/velocity

The cross-sectional area of the flow is calculated from a depth measurement and the average velocity of the flow is measured directly (Doppler and propeller methods are common). Velocity times the cross-sectional area yields a flow rate which can be integrated into volumetric flow. There are two types of area velocity flowmeter: (1) wetted; and (2) non-contact. Wetted area velocity sensors have to be typically mounted on the bottom of a channel or river and use Doppler to measure the velocity of the entrained particles. With depth and a programmed cross-section this can then provide discharge flow measurement. Non-contact devices that use laser or radar are mounted above the channel and measure the velocity from above and then use ultrasound to measure the depth of the water from above. Radar devices can only measure surface velocities, whereas laser-based devices can measure velocities sub-surface.

Dye testing

A known amount of dye (or salt) per unit time is added to a flow stream. After complete mixing, the concentration is measured. The dilution rate equals the flow rate.

Acoustic Doppler velocimetry

Acoustic Doppler velocimetry (ADV) is designed to record instantaneous velocity components at a single point with a relatively high frequency. Measurements are performed by measuring the velocity of particles in a remote sampling volume based upon the Doppler shift effect.

Thermal mass flowmeters

Thermal mass flowmeters generally use combinations of heated elements and temperature sensors to measure the difference between static and flowing heat transfer to a fluid and infer its flow with a knowledge of the fluid's specific heat and density. The fluid temperature is also measured and compensated for. If the density and specific heat characteristics of the fluid are constant, the meter can provide a direct mass flow readout, and does not need any additional pressure temperature compensation over their specified range.

Technological progress has allowed the manufacture of thermal mass flowmeters on a microscopic scale as MEMS sensors; these flow devices can be used to measure flow rates in the range of nanoliters or microliters per minute.

Thermal mass flowmeter (also called thermal dispersion or thermal displacement flowmeter) technology is used for compressed air, nitrogen, helium, argon, oxygen, and natural gas. In fact, most gases can be measured as long as they are fairly clean and non-corrosive. For more aggressive gases, the meter may be made out of special alloys (e.g. Hastelloy), and pre-drying the gas also helps to minimize corrosion.

Today, thermal mass flowmeters are used to measure the flow of gases in a growing range of applications, such as chemical reactions or thermal transfer applications that are difficult for other flowmetering technologies. Some other typical applications of flow sensors can be found in the medical field like, for example, CPAP devices, anesthesia equipment or respiratory devices. This is because thermal mass flowmeters monitor variations in one or more of the thermal characteristics (temperature, thermal conductivity, and/or specific heat) of gaseous media to define the mass flow rate.

The MAF sensor

In many late model automobiles, a Mass Airflow (MAF) sensor is used to accurately determine the mass flow rate of intake air used in the internal combustion engine. Many such mass flow sensors use a heated element and a downstream temperature sensor to indicate the air flowrate. Other sensors use a spring-loaded vane. In either case, the vehicle's electronic control unit interprets the sensor signals as a real-time indication of an engine's fuel requirement.

Vortex flowmeters

Another method of flow measurement involves placing a bluff body (called a shedder bar) in the path of the fluid. As the fluid passes this bar, disturbances in the flow called vortices are created. The vortices trail behind the cylinder, alternatively from each side of the bluff body. This vortex trail is called the Von Kármán vortex street after von Kármán's 1912 mathematical description of the phenomenon. The frequency at which these vortices alternate sides is essentially proportional to the flow rate of the fluid. Inside, atop, or downstream of the shedder bar is a sensor for measuring the frequency of the vortex shedding. This sensor is often a piezoelectric crystal, which produces a small, but measurable, voltage pulse every time a vortex is created. Since the frequency of such a voltage pulse is also proportional to the fluid velocity, a volumetric flow rate is calculated using the cross-sectional area of the flowmeter. The frequency is measured and the flow rate is calculated by the flowmeter electronics using the equation where is the frequency of the vortices, the characteristic length of the bluff body, is the velocity of the flow over the bluff body, and is the Strouhal number, which is essentially a constant for a given body shape within its operating limits.

Sonar flow measurement

Sonar flowmeters are non-intrusive clamp-on devices that measure flow in pipes conveying slurries, corrosive fluids, multiphase fluids and flows where insertion type flowmeters are not desired. Sonar flowmeters have been widely adopted in mining, metals processing, and upstream oil and gas industries where traditional technologies have certain limitations due to their tolerance to various flow regimes and turn down ratios.

Sonar flowmeters have the capacity of measuring the velocity of liquids or gases non-intrusively within the pipe and then leverage this velocity measurement into a flow rate by using the cross-sectional area of the pipe and the line pressure and temperature. The principle behind this flow measurement is the use of underwater acoustics.

In underwater acoustics, to locate an object underwater, sonar uses two knowns:

- The speed of sound propagation through the array (i.e., the speed of sound through seawater)

- The spacing between the sensors in the sensor array

and then calculates the unknown:

- The location (or angle) of the object.

Likewise, sonar flow measurement uses the same techniques and algorithms employed in underwater acoustics, but applies them to flow measurement of oil and gas wells and flow lines.

To measure flow velocity, sonar flowmeters use two knowns:

- The location (or angle) of the object, which is 0 degrees since the flow is moving along the pipe, which is aligned with the sensor array

- The spacing between the sensors in the sensor array

and then calculates the unknown:

- The speed of propagation through the array (i.e. the flow velocity of the medium in the pipe).

Electromagnetic, ultrasonic and Coriolis flowmeters

Modern innovations in the measurement of flow rate incorporate electronic devices that can correct for varying pressure and temperature (i.e. density) conditions, non-linearities, and for the characteristics of the fluid.

Magnetic flowmeters

Magnetic flowmeters, often called "mag meter"s or "electromag"s, use a magnetic field applied to the metering tube, which results in a potential difference proportional to the flow velocity perpendicular to the flux lines. The potential difference is sensed by electrodes aligned perpendicular to the flow and the applied magnetic field. The physical principle at work is Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction. The magnetic flowmeter requires a conducting fluid and a nonconducting pipe liner. The electrodes must not corrode in contact with the process fluid; some magnetic flowmeters have auxiliary transducers installed to clean the electrodes in place. The applied magnetic field is pulsed, which allows the flowmeter to cancel out the effect of stray voltage in the piping system.

Non-contact electromagnetic flowmeters

A Lorentz force velocimetry system is called Lorentz force flowmeter (LFF). An LFF measures the integrated or bulk Lorentz force resulting from the interaction between a liquid metal in motion and an applied magnetic field. In this case, the characteristic length of the magnetic field is of the same order of magnitude as the dimensions of the channel. It must be addressed that in the case where localized magnetic fields are used, it is possible to perform local velocity measurements and thus the term Lorentz force velocimeter is used.

Ultrasonic flowmeters (Doppler, transit time)

There are two main types of ultrasonic flowmeters: Doppler and transit time. While they both utilize ultrasound to make measurements and can be non-invasive (measure flow from outside the tube, pipe or vessel, also called clamp-on device), they measure flow by very different methods.

Ultrasonic transit time flowmeters measure the difference of the transit time of ultrasonic pulses propagating in and against the direction of flow. This time difference is a measure for the average velocity of the fluid along the path of the ultrasonic beam. By using the absolute transit times both the averaged fluid velocity and the speed of sound can be calculated. Using the two transit times and and the distance between receiving and transmitting transducers and the inclination angle one can write the equations: and where is the average velocity of the fluid along the sound path and is the speed of sound.

With wide-beam illumination transit time ultrasound can also be used to measure volume flow independent of the cross-sectional area of the vessel or tube.

Ultrasonic Doppler flowmeters measure the Doppler shift resulting from reflecting an ultrasonic beam off the particulates in flowing fluid. The frequency of the transmitted beam is affected by the movement of the particles; this frequency shift can be used to calculate the fluid velocity. For the Doppler principle to work, there must be a high enough density of sonically reflective materials such as solid particles or air bubbles suspended in the fluid. This is in direct contrast to an ultrasonic transit time flowmeter, where bubbles and solid particles reduce the accuracy of the measurement. Due to the dependency on these particles, there are limited applications for Doppler flowmeters. This technology is also known as acoustic Doppler velocimetry.

One advantage of ultrasonic flowmeters is that they can effectively measure the flow rates for a wide variety of fluids, as long as the speed of sound through that fluid is known. For example, ultrasonic flowmeters are used for the measurement of such diverse fluids as liquid natural gas (LNG) and blood. One can also calculate the expected speed of sound for a given fluid; this can be compared to the speed of sound empirically measured by an ultrasonic flowmeter for the purposes of monitoring the quality of the flowmeter's measurements. A drop in quality (change in the measured speed of sound) is an indication that the meter needs servicing.

Coriolis flowmeters

Using the Coriolis effect that causes a laterally vibrating tube to distort, a direct measurement of mass flow can be obtained in a coriolis flowmeter. Furthermore, a direct measure of the density of the fluid is obtained. Coriolis measurement can be very accurate irrespective of the type of gas or liquid that is measured; the same measurement tube can be used for hydrogen gas and bitumen without recalibration.

Coriolis flowmeters can be used for the measurement of natural gas flow.

Laser Doppler flow measurement

A beam of laser light impinging on a moving particle will be partially scattered with a change in wavelength proportional to the particle's speed (the Doppler effect). A laser Doppler velocimeter (LDV), also called a laser Doppler anemometer (LDA), focuses a laser beam into a small volume in a flowing fluid containing small particles (naturally occurring or induced). The particles scatter the light with a Doppler shift. Analysis of this shifted wavelength can be used to directly, and with great precision, determine the speed of the particle and thus a close approximation of the fluid velocity.

A number of different techniques and device configurations are available for determining the Doppler shift. All use a photodetector (typically an avalanche photodiode) to convert the light into an electrical waveform for analysis. In most devices, the original laser light is divided into two beams. In one general LDV class, the two beams are made to intersect at their focal points where they interfere and generate a set of straight fringes. The sensor is then aligned to the flow such that the fringes are perpendicular to the flow direction. As particles pass through the fringes, the Doppler-shifted light is collected into the photodetector. In another general LDV class, one beam is used as a reference and the other is Doppler-scattered. Both beams are then collected onto the photodetector where optical heterodyne detection is used to extract the Doppler signal.

Calibration

Even though ideally the flowmeter should be unaffected by its environment, in practice this is unlikely to be the case. Often measurement errors originate from incorrect installation or other environment dependent factors. In situ methods are used when flowmeter is calibrated in the correct flow conditions. The result of a flowmeter calibration will result in two related statistics: a performance indicator metric and a flow rate metric.

Transit time method

For pipe flows a so-called transit time method is applied where a radiotracer is injected as a pulse into the measured flow. The transit time is defined with the help of radiation detectors placed on the outside of the pipe. The volume flow is obtained by multiplying the measured average fluid flow velocity by the inner pipe cross-section. This reference flow value is compared with the simultaneous flow value given by the flow measurement to be calibrated.

The procedure is standardised (ISO 2975/VII for liquids and BS 5857-2.4 for gases). The best accredited measurement uncertainty for liquids and gases is 0.5%.

Tracer dilution method

The radiotracer dilution method is used to calibrate open channel flow measurements. A solution with a known tracer concentration is injected at a constant known velocity into the channel flow. Downstream the tracer solution is thoroughly mixed over the flow cross-section, a continuous sample is taken and its tracer concentration in relation to that of the injected solution is determined. The flow reference value is determined by using the tracer balance condition between the injected tracer flow and the diluting flow. The procedure is standardised (ISO 9555-1 and ISO 9555-2 for liquid flow in open channels). The best accredited measurement uncertainty is 1%.

See also

- Anemometer

- Automatic meter reading

- Flowmeter error

- Ford viscosity cup

- Gas meter

- Ultrasonic flow meter

- Laser Doppler velocimetry

- Primary flow element

- Water meter

References

- Béla G. Lipták, Flow Measurement, CRC Press, 1993 ISBN 080198386X page 88

- Furness, Richard A. (1989). Fluid flow measurement. Harlow: Longman in association with the Institute of Measurement and Control. p. 21. ISBN 0582031656.

- Holman, J. Alan (2001). Experimental methods for engineers. Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-366055-4.

- Report Number 7: Measurement of Natural Gas by Turbine Meters (Report). American Gas Association. February 2006.

- Arregui, Francisco; Cabrera, Enrique Jr.; Cobacho, Ricardo (2006). Integrated Water Meter Management. London: IWA Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 9781843390343.

- Herschel, Clemens. (1898). Measuring Water. Providence, Rhode Island: Builders Iron Foundry.

- Lipták, Flow Measurement, p. 85

- Report Number 3: Orifice Metering of Natural Gas and Other Related Hydrocarbon Fluids (Report). American Gas Association. September 2012.

- "Cone DP Meter Calibration Issues". Pipeline & Gas Journal. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Miller, Richard W. (1996). Flow Measurement Engineering Handbook (3rd ed.). Mcgraw Hill. p. 6.16–6.18. ISBN 0070423660.

- Bean, Howard S., ed. (1971). Fluid Meters, Their Theory and Application (6th ed.). New York: The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. pp. 77–78.

- Stefaan J.R.Simons, Concepts of Chemical Engineering 4 Chemists Royal Society of Chemistry,(2007) ISBN 978-0-85404-951-6, page 75

- "Flare Metering with Optics" (PDF). photon-control.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- "Desk.com – Site Not Found (Subdomain Does Not Exist)". help.openchannelflow.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- Severn, Richard. "Environment Agency Field Test Report – TIENet 360 LaserFlow" (PDF). RS Hydro. RS Hydro-Environment Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Chanson, Hubert (2008). Acoustic Doppler Velocimetry (ADV) in the Field and in Laboratory: Practical Experiences. in Frédérique Larrarte and Hubert Chanson, Experiences and Challenges in Sewers: Measurements and Hydrodynamics. International Meeting on Measurements and Hydraulics of Sewers IMMHS'08, Summer School GEMCEA/LCPC, Bouguenais, France, 19–21 August 2008, Hydraulic Model Report No. CH70/08, Div. of Civil Engineering, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, Dec., pp. 49–66. ISBN 978-1-86499-928-0. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

- An Overview of Non-Invasive Flow Measurements Method (PDF). The Americas Workshop 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- Field Trials and Pragmatic Development of SONAR Flow Meter Technology (PDF). North Sea Flow Measurement Workshop. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- Drost, CJ (1978). "Vessel Diameter-Independent Volume Flow Measurements Using Ultrasound". Proceedings of San Diego Biomedical Symposium. 17: 299–302.

- American Gas Association Report Number 9

- Baker, Roger C. (2003). Introductory guide to Flow Measurement. ASME. ISBN 0-7918-0198-5.

- American Gas Association Report Number 11

- Adrian, R. J., editor (1993); Selected on Laser Doppler Velocimetry, S.P.I.E. Milestone Series, ISBN 978-0-8194-1297-3

- Cornish, D (1994). "Instrument performance". Measurement and Control. 27 (10): 323–328. doi:10.1177/002029409402701004.

- Baker, Roger C. (2016). Flow Measurement Handbook. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-04586-6.

- Paton, Richard. "Calibration and Standards in Flow Measurement" (PDF). Handbook of Measuring System Design. Wiley. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ^ Finnish Accreditation Service

, and the

, and the  .

.

, mass and volumetric flow rates may be related by

, mass and volumetric flow rates may be related by  .

.

where

where  is the distance between the laser beams and

is the distance between the laser beams and  is the time interval.

is the time interval.

where

where  is a constant,

is a constant,  is the water level, and

is the water level, and  is an exponent which varies with the device used; or it is converted according to empirically derived level/flow data points (a "flow curve"). The flow rate can then be integrated over time into volumetric flow. Level to flow devices are commonly used to measure the flow of surface waters (springs, streams, and rivers), industrial discharges, and sewage. Of these,

is an exponent which varies with the device used; or it is converted according to empirically derived level/flow data points (a "flow curve"). The flow rate can then be integrated over time into volumetric flow. Level to flow devices are commonly used to measure the flow of surface waters (springs, streams, and rivers), industrial discharges, and sewage. Of these,  where

where  is the frequency of the vortices,

is the frequency of the vortices,  the characteristic length of the bluff body,

the characteristic length of the bluff body,  is the velocity of the flow over the bluff body, and

is the velocity of the flow over the bluff body, and  is the

is the  and

and  and the distance between receiving and transmitting transducers

and the distance between receiving and transmitting transducers  one can write the equations:

one can write the equations:

and

and

where

where  is the average velocity of the fluid along the sound path and

is the average velocity of the fluid along the sound path and  is the speed of sound.

is the speed of sound.