| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Four Treasures of the Study" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Four Treasures of the Study | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 文房四寶 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 文房四宝 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 紙墨筆硯 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 纸墨笔砚 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | văn phòng tứ bảo | ||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 文房四寶 | ||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 문방사우 | ||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 文房四友 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 文房四宝 | ||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ぶんぼうしほう | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

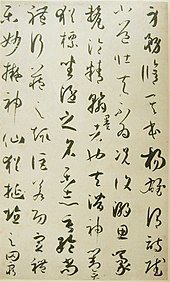

Four Treasures of the Study is an expression used to denote the brush, ink, paper and ink stone used in Chinese calligraphy and spread into other East Asian calligraphic traditions. The name appears to originate in the time of the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589 AD).

Four Treasures

The Four Treasures is expressed in a four-word couplet: "The four treasures of the study: Brush, Ink, Paper, Inkstone." (Chinese: 文房四寶:筆、墨、紙、硯; pinyin: Wén fáng sì bǎo: bǐ, mò, zhǐ, yàn) In the couplet mentioned, each of the Treasures is referred to by a single epithet; however, each of these are usually known by a compound name (i.e. The Brush: Chinese: 毛筆; pinyin: máobǐ, literally "hair/brush pen). The individual treasures have a "treasured" form, each being produced in certain areas of China as a speciality for those scholars who would use them.

Brush

Main article: Ink brush

The brush (simplified Chinese: 毛笔; traditional Chinese: 毛筆; pinyin: máo bǐ, Korean: 붓 but, Vietnamese: 筆 bút, Japanese: 筆 fude, Ryukyuan: fudi) is the oldest of the Four Treasures, with archaeological evidence dating to Zhou dynasty (1045 BC–256 BC) illustrations on ancient bones. The oldest brush so far dates to Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD). Brushes are generally made from animal hair, or —in certain situations—the first hair taken from a baby's head (said to bring good luck in the Imperial examinations). Brush handles are commonly constructed from bamboo, but special brushes may have handles of sandalwood, jade, carved bone/ivory, or other precious materials.

Modern brushes are primarily white goat hair (羊毫), black rabbit hair (紫毫), yellow weasel hair (黄鼠毫/狼毫), or a combination mix. Ancient brushes, and some of the more valuable ones available on the market may be made with the hair of any number of animals. Each type of hair has a specific ink capacity, giving distinct brush strokes. Different brushes are used for different styles of calligraphy and writing.

Brushes are classed as soft (軟毫), mixed (兼毫) or hard (硬毫). Hair is laboriously sorted by softness, hardness, thickness, & length, then bundled for specific uses. The most famous and highly prized brushes are a mix of yellow weasel, goat and rabbit hair, known as Húbǐ (湖筆); highly prized since the Ming dynasty (late 14th century) they are currently made in Shanlian (善琏), a town in the Nanxun District, prefecture-level city of Huzhou, of Zhejiang province (浙江).

Ink

Main article: Inkstick

The Inkstick (Chinese: 墨; pinyin: mò, Korean: 묵 muk, Vietnamese: 墨 mực, Japanese: 墨 sumi, Ryukyuan: shimi) is an artificial ink developed during the Han dynasty. These first writing inks were based on naturally occurring minerals like graphite and vermilion; earliest inks were probably liquids and not preserved. Modern inksticks are generally made of soots from one of three sources, including lacquer soot, pine soot, and oil soot. Soots are collected, then mixed with glue. Higher quality inksticks also use powdered spices and herbs, adding to aroma and providing some protection to the ink itself. The glue, soot, and spice mixture is then pressed into shape and allowed to dry. This process can take 6 weeks, depending on an inkstick's dimensions.

The best ink sticks are fine grained and have a light, slightly ringing sound when tapped. They are often decorated with poems, calligraphy, or bas relief, and painted. These particular articles are highly collectable, and often acquired like stamps. The inksticks in highest regard, known as Huīmò (徽墨), contain musk, borneol and other precious aromatics of Chinese medicine. They are still produced today in Shexian (歙县) in Anhui province (安徽).

Paper

Main article: Xuan Paper

Paper (simplified Chinese: 纸; traditional Chinese: 紙; Pinyin: zhǐ, Korean: 종이 jong'i, Vietnamese: 絏 giấy, Japanese: 紙 kami) was first developed in China in the first decade of 100 AD. Previous to its invention, bamboo slips and silks were used for writing material. Several methods of paper production developed over the centuries in China. However, the paper which was considered of highest value was that of the Jingxian (泾县) in Anhui province.

This particular form of paper, known as Xuānzhǐ (宣紙), is soft, fine-textured, moth resistant, has a high tensile strength, and remarkable longevity for such a product – so much so that it has a reputation for lasting "1,000 years". The quality of the paper depends on the processing methods used to produce it. Paper may be unprocessed, half processed or processed. The processing determines how well ink or paint is absorbed into the fibre of the paper, as well as the stiffness of the paper itself. Unprocessed papers are very absorbent and quite malleable, whereas processed papers are far more resistant to absorption and are stiffer.

Inkstone

Main article: Inkstone

The inkstone (Chinese: simplified Chinese: 砚; traditional Chinese: 硯; Pinyin: yàn, Korean: 벼루 byeoru, Vietnamese: 硯 nghiên, Japanese: 硯 suzuri) is used to grind the ink stick into powder. This powder is then mixed with water in a well in the inkstone in order to produce usable ink for calligraphy. The most ideal water for use in ink is slightly salty. Ink was first prepared using a mortar and pestle, but with the advent of inksticks this method slowly vanished. The stone used is generally of a relatively fine whetstone type.

The earliest known inkstones date back to the Han dynasty. The production of inkstones reached its zenith in the Tang and Song dynasties with inkstones becoming extremely intricate works of art. The most highly sought-after inkstones originated in four locations in China. Duanshi stones (端石硯) from Duanxi in Guangdong, She stones (歙硯) from Shexian in Anhui, Taohe stones (洮河硯) from the Tao River in South Gansu and Chengni ceramic stones (澄泥硯) which are manufactured by a process which is said to have been developed in Luoyang in Henan.

Tools of the Scholar

Classical scholars had more than just the Four treasures in their studies. The other "Treasures" include the brush-holder (笔架), brush-hanger (笔挂), paperweights (镇纸), the brush-rinsing pot (笔洗), and the seal (圖章) and seal-ink (印泥).

For painting, Chinese pigments are also used.

Gallery

-

Inkstone and inkstick

Inkstone and inkstick

-

Seal and seal paste

Seal and seal paste

-

Paper, paperweight and desk pad

Paper, paperweight and desk pad

-

Brushes; head types, compositions and brush sizes

Brushes; head types, compositions and brush sizes

See also

- Four Gentlemen

- Three Friends of Winter

- Mirror Flower, Water Moon

- East Asian calligraphy styles:

- Bamboo and wooden slips

References

- "Cựu giám đốc thư viện mê cổ vật xứ Nghệ". VnExpress.

- "남성의 애장품, 문방사우와 서안". National Folk Museum of Korea.

- "「文房四宝」を半減させるな!". Nikkei.

- ^ Chinesetoday.com. "Chinesetoday.com Archived June 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." 趣談「文房四寶」. Retrieved on 2010-11-27.

- Big5.xinhuanet.com. "Big5.xinhuanet.com." 走近文房四寶. Retrieved on 2010-11-27.

External links

The dictionary definition of four treasures of the study at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of four treasures of the study at Wiktionary