In theoretical physics, a gauge anomaly is an example of an anomaly: it is a feature of quantum mechanics—usually a one-loop diagram—that invalidates the gauge symmetry of a quantum field theory; i.e. of a gauge theory.

All gauge anomalies must cancel out. Anomalies in gauge symmetries lead to an inconsistency, since a gauge symmetry is required in order to cancel degrees of freedom with a negative norm which are unphysical (such as a photon polarized in the time direction). Indeed, cancellation occurs in the Standard Model.

The term gauge anomaly is usually used for vector gauge anomalies. Another type of gauge anomaly is the gravitational anomaly, because coordinate reparametrization (called a diffeomorphism) is the gauge symmetry of gravitation.

Calculation of the anomaly

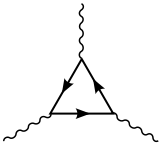

Anomalies occur only in even spacetime dimensions. For example, the anomalies in the usual 4 spacetime dimensions arise from triangle Feynman diagrams.

Vector gauge anomalies

In vector gauge anomalies (in gauge symmetries whose gauge boson is a vector), the anomaly is a chiral anomaly, and can be calculated exactly at one loop level, via a Feynman diagram with a chiral fermion running in the loop with n external gauge bosons attached to the loop where where is the spacetime dimension.

Let us look at the (semi)effective action we get after integrating over the chiral fermions. If there is a gauge anomaly, the resulting action will not be gauge invariant. If we denote by the operator corresponding to an infinitesimal gauge transformation by ε, then the Frobenius consistency condition requires that

for any functional , including the (semi)effective action S where is the Lie bracket. As is linear in ε, we can write

where Ω is d-form as a functional of the nonintegrated fields and is linear in ε. Let us make the further assumption (which turns out to be valid in all the cases of interest) that this functional is local (i.e. Ω(x) only depends upon the values of the fields and their derivatives at x) and that it can be expressed as the exterior product of p-forms. If the spacetime M is closed (i.e. without boundary) and oriented, then it is the boundary of some d+1 dimensional oriented manifold M. If we then arbitrarily extend the fields (including ε) as defined on M to M with the only condition being they match on the boundaries and the expression Ω, being the exterior product of p-forms, can be extended and defined in the interior, then

The Frobenius consistency condition now becomes

As the previous equation is valid for any arbitrary extension of the fields into the interior,

Because of the Frobenius consistency condition, this means that there exists a d+1-form Ω (not depending upon ε) defined over M satisfying

Ω is often called a Chern–Simons form.

Once again, if we assume Ω can be expressed as an exterior product and that it can be extended into a d+1 -form in a d+2 dimensional oriented manifold, we can define

in d+2 dimensions. Ω is gauge invariant:

as d and δε commute.

See also

References

- Treiman, Sam, and Roman Jackiw, (2014). Current algebra and anomalies. Princeton University Press.

- Cheng, T.P.; Li, L.F. (1984). Gauge Theory of Elementary Particle Physics. Oxford Science Publications.

where

where  is the

is the

the operator corresponding to an infinitesimal gauge transformation by ε, then the

the operator corresponding to an infinitesimal gauge transformation by ε, then the

, including the (semi)effective action S where is the

, including the (semi)effective action S where is the  is linear in ε, we can write

is linear in ε, we can write