| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

An IRCd, short for Internet Relay Chat daemon, is server software that implements the IRC protocol, enabling people to talk to each other via the Internet (exchanging textual messages in real time). It is distinct from an IRC bot that connects outbound to an IRC channel.

The server listens to connections from IRC clients on a set of TCP ports. When the server is part of an IRC network, it also keeps one or more established connections to other servers/daemons.

The term ircd originally referred to only one single piece of software, but it eventually became a generic reference to any implementation of an IRC daemon. However, the original version is still distributed under the same name, and this article discusses both uses.

History

| This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (January 2015) |

The original IRCd was known as 'ircd', and was authored by Jarkko Oikarinen (WiZ on IRC) in 1988. He received help from a number of others, such as Markku Savela (msa on IRC), who helped with the 2.2+msa release, etc.

In its first revisions, IRC did not have many features that are taken for granted today, such as named channels and channel operators. Channels were numbered – channel 4 and channel 57, for example – and the channel topic described the kind of conversation that took place in the channel. One holdover of this is that joining channel 0 causes a client to leave all the channels it is presently on: "CHANNEL 0" being the original command to leave the current channel.

The first major change to IRC, in version 2.5, was to add named channels – "+channels". "+channels" were later replaced with "#channels" in version 2.7, numeric channels were removed entirely and channel bans (mode +b) were implemented.

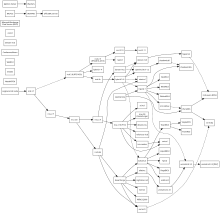

Around version 2.7, there was a small but notable dispute, which led to ircu – the Undernet fork of ircd.

irc2.8 added "&channels" (those that exist only on the current server, rather than the entire network) and "!channels" (those that are theoretically safe from suffering from the many ways that a user could exploit a channel by "riding a netsplit"), and is the baseline release from which nearly all current implementations are derived.

Around 2.8 came the concept of nick and channel delay, a system designed to help curb abusive practices such as takeovers and split riding. This was not agreed on by the majority of modern IRC (EFnet, DALnet, Undernet, etc.) – and thus, 2.8 was forked into a number of different daemons using an opposing theory known as TS – or time stamping, which stored a unique time stamp with each channel or nickname on the network to decide which was the 'correct' one to keep.

Time stamping itself has been revised several times to fix various issues in its design. The latest versions of such protocols are:

- the TS6 protocol, which is used by EFnet, and Hybrid and Ratbox based servers amongst others

- the P10 protocol, which is used by Undernet and ircu based servers.

While the client-to-server protocols are at least functionally similar, server-to-server protocols differ widely (TS5, P10, and ND/CD server protocols are incompatible), making it very difficult to "link" two separate implementations of the IRC server. Some "bridge" servers do exist, to allow linking of, for example, 2.10 servers to TS5 servers, but these are often accompanied with restrictions of which parts of each protocol may be used, and are not widely deployed.

Significant releases based on 2.8 included:

- 2.8.21+CS, developed by Chris Behrens (Comstud)

- 2.8+th, Taner Halicioglu's patchset, which later became

- Hybrid IRCd, originally developed by Jon Lusky (Rodder) and Diane Bruce (Dianora) as 2.8/hybrid, later joined by a large development team.

- 2.9, 2.10, 2.11, ... continue the development of the original codebase,

The original code base continued to be developed mainly for use on the IRCnet network. New server-to-server protocols were introduced in version 2.10, released in 1998, and in 2.11, first released in 2004, and current as of 2007. This daemon is used by IRCnet and it can be found at http://www.irc.org/ftp/irc/server/ The original ircd is free software, licensed under the GNU General Public License. This development line produced the 4 IRC RFCs released after RFC 1459, which document this server protocol exclusively.

2.8.21+CS and Hybrid IRCd continue to be used on EFnet, with ircd-ratbox (an offshoot of ircd-hybrid) as of 2004 being the most popular.

Sidestream versions

More recently, several irc daemons were written from scratch, such as ithildin, InspIRCd, csircd (also written by Chris Behrens), ConferenceRoom, Microsoft Exchange Chat Service, WeIRCd, or IRCPlus/IRCXPro.

These attempts have met with mixed success, and large doses of skepticism from the existing IRC development community. With each new IRCd, a slightly different version of the IRC protocol is used, and many IRC clients and bots are forced to compromise on features or vary their implementation based on the server to which they are connected. These are often implemented for the purpose of improving usability, security, separation of powers, or ease of integration with services. Possibly one of the most common and visible differences is the inclusion or exclusion of the half-op channel operator status (which is not a requirement of the RFCs).

Features

Ports

The officially assigned port numbers are 194 ("irc"), 529 ("irc-serv"), and 994 ("ircs"). However, these ports are in the privileged range (0–1024), which on a Unix-like system means that the daemon would historically have to have superuser privileges in order to open them. For various security reasons this used to be undesirable.

The common ports for an IRCd process are 6665 to 6669, with 6667 being the historical default. These ports can be opened by a non-superuser process, and they became widely used.

Connections

Running a large IRC server, one that has more than a few thousand simultaneous users, requires keeping a very large number of TCP connections open for long periods. Very few ircds are multithreaded as nearly every action needs to access (at least read and possibly modify) the global state.

The result is that the best platforms for ircds are those that offer efficient mechanisms for handling huge numbers of connections in a single thread. Linux offers this ability in the form of epoll, in kernel series newer than 2.4.x. FreeBSD (since 4.1) and OpenBSD (since 2.9) offers kqueue. Solaris has had /dev/poll since version 7, and from version 10 onwards has IOCP (I/O Completion Ports). Windows has supported IOCP since Windows NT 3.5. The difference made by these new interfaces can be dramatic. IRCU developers have mentioned increases in the practical capacity per server from 10,000 users to 20,000 users.

TLS (Transport Layer Security)

Some IRCd support Transport Layer Security, or TLS, for those who don't, it is still possible to use SSL via Stunnel. The unofficial, but most often used port for TLS IRCd connections is 6697. More recently, as a security enhancement and usability enhancement, various client and server authors have begun drafting a standard known as the STARTTLS standard which allows for TLS and plain text connections to co-exist on the same TCP port.

IPv4 and IPv6

IRC daemons support IPv4, and some also support IPv6. In general, the difference between IPv6 and IPv4 connections to IRC is purely academic and the service operates in much the same manner through either protocol.

Clustering

Large IRC networks consist of multiple servers for horizontal scaling purposes. There are several IRC protocol extensions for these purposes.

IRCX

IRCX (Internet Relay Chat eXtensions) is an extension to the IRC protocol developed by Microsoft

P10

The P10 protocol is an extension to the Internet Relay Chat protocol for server to server communications developed by the Undernet Coder Committee to use in their ircu server software. It is similar in purpose to IRCX and EFnet TS5/TS6 protocols and implements nick and channel timestamping for handling nick collisions and netsplit channel riding, respectively. Other IRCd's that utilize this protocol extension include beware ircd.

TS6

The TS6 protocol is an extension to the Internet Relay Chat protocol for server to server communications developed initially by the developers of ircd-ratbox. It has been extended by various IRC software and has the feature that proper implementations of TS6 can link to each other by using feature negotiation—even if features are disparate.

Configuration

Jupe

Juping a server, a channel, or a nickname refers to the practice of blocking said channel or nickname on the server or network or said server on the network. One possible explanation of how this term came about is that it is named after the oper named Jupiter, who gained control of the nickname NickServ on EFnet. EFnet does not offer services such as NickServ; Jupiter gained control of the nickname as he (among other operators) did not believe nicknames should be owned. Today, EFnet opers jupe nicknames that are used as services on other networks.

A nickname or server jupe takes advantage of the fact that certain identifiers are unique; by using an identifier, one acquires an exclusive lock that prevents other users from making use of it.

Officially sanctioned jupes may also utilize services or server configuration options to enforce the jupe, such as when a compromised server is juped to prevent it from harming the network.

In practice IRC operators now use jupe configurations to administratively make channel or nicknames unavailable. A channel jupe refers to a server specific ban of a channel, which means that a specific channel cannot be joined when connected to a certain server, but other servers may allow a user to join the channel. This is a way of banning access to problematic channels.

O-line

An O-line (frequently also spelled as O:line; on IRCds that support local operators, the O-lines of those are called o:lines with a lower-case O), shortened from Operator Line and derived from the line-based configuration file of the original IRCd, is a line of code in an IRC daemon configuration file that determines which users can become an IRC operator and which permissions they get upon doing so. The name comes from the prefix used for the line in the original IRCd, a capital O. The O-line specifies the username, password, operator flags, and hostmask restrictions for a particular operator. A server may have many O-lines depending on the administrative needs of the server and network.

Operator flags are used to describe the permissions an operator is granted. While some IRC operators may be in charge of network routing, others may be in charge of network abuse, making their need for certain permissions different. Operator flags available vary widely depending on which IRC daemon is in use. Generally, more feature rich IRC daemons tend to have more operator flags, and more traditional IRC daemons have fewer.

An O-line may also be set so that only users of a certain hostmask or IP address can gain IRC operator status using that O-line. Using hostmasks and IP addresses in the O-line requires the IP address to remain the same but provides additional security.

K-line

When a user is k-lined (short for kill line), the user is banned from a certain server, either for a certain amount of time or permanently. Once the user is banned, they are not allowed back onto that server. This is recorded as a line in the server's IRC daemon configuration file prefixed with the letter "K", hence "K-line".

Some IRC daemons, including ircd-hybrid and its descendants, can be configured to propagate K-lines to some or all other servers on a network. In such a configuration, K-lines are effectively global bans similar to G-lines.

While the precise reason for the disconnection varies from case to case, usual reasons involve some aspect of the client or the user it is issued against.

- User behavior

- K-lines can be given due to inappropriate behavior on the part of the user, such as "nickname colliding", mode "hacking", multiple channel flooding, harassing other users via private messaging features, "spamming" etc., or in the case of older networks without timestamping, split riding, which cannot be corrected through use of channel operator privileges alone.

- Client software

- Some IRC daemons can be configured to scan for viruses or other vulnerabilities in clients connecting to them, and will react in various ways according to the result. Outdated and insecure client software might be blocked to protect other network users from vulnerabilities, for instance. Some networks will disconnect clients operating on/via open proxies, or running an insecure web server.

- Geographic location

- An IRC network operating multiple servers in different locales will attempt to reduce the distance between a client and a server. This is often achieved by disconnecting (and/or banning) clients from distant locales in favour of local ones.

There are a number of other network "lines" relating to the K-line. Modern IRC daemons will also allow IRC operators to set these lines during normal operation, where access to the server configuration file is not routinely needed.

G-line

"G-line" redirects here. For other uses, see G-line (disambiguation).A G-line or global kill line (also written G:line) is a global network ban applied to a user; the term comes from Undernet but on DALnet a similar concept known as an AKill was used.

G-lines are sometimes stored in the configuration file of the IRCd, although some networks, who handle K-lines through the IRC services, prefer to have them stored in their service's configuration files. Whenever a G-lined person attempts to connect to the IRC network, either the services or the IRC daemon will automatically disconnect the client, often displaying a message explaining the reasoning behind the ban.

G-lines are a variant of K-lines, which work in much the same way, except K-lines only disconnect clients on one server of the network. G-lines are normally applied to a user who has received a K-line on one server but continues to abuse the network by connecting via a different server. G-lines are often regarded as an extreme measure, only to be used in cases of repeated abuse when extensive attempts have been made to reason with the offending user. Therefore, especially on larger networks, often only very high ranking global IRC operators are permitted to set them, while K-lines, which are mostly regarded as a local affair, are left to the operators of the individual server in the network.

G-lines also work slightly differently from K-lines. G-lines are typically set as *@IPaddress or *@host, with the first being the better option. If the *@host option is used, the server must conduct a reverse DNS lookup on the user and then compare the returned host to the hosts in the G-line list. This results in delay, and, if the DNS doesn't return correct results, the banned user may still get on the network.

Z-line

"Zline" redirects here. For other uses, see Z-line.A Z-line or zap line (also written Z:line) is similar to a K-line, but applied to a client's IP address range, and is considered to be used in extreme cases. Because a Z-line does not have to check usernames (identd) or resolved hostnames, it can be applied to a user before they send any data at all upon connection. Therefore, a Z-line is more efficient and uses fewer resources than a K-line or G-line when banning large numbers of users.

In some IRC daemons such as ircd-hybrid, this is called a D-line (deny line) or an X-line.

Z-lines are sometimes stored in the configuration file of the IRCd, although some networks, who handle lines through the IRC services, prefer to have them stored in their service's configuration files. Whenever a Z-lined person attempts to connect to the IRC network, either the services or the IRC daemon will automatically disconnect the client, often displaying a message explaining the reasoning behind the ban.

Z-lines are a variant of K-lines, which work in much the same way. Most Z-lines are "awarded" to people who abuse the network as a whole (on smaller networks, these are more frequently issued for isolated incidents).

Z-lines also work slightly differently from K-lines. Z-lines are typically set as *@IP or *@host, with the first being the better option. Z-lines do not wait for an ident response from the connecting user, but immediately close the socket once the user's IP is compared to the Z-line list and a match is found. If the *@host option is used, the server must conduct a reverse DNS lookup on the user and then compare the returned host to the hosts in the Z-line list. This can result in delays, or if the DNS doesn't return correctly, banned users could still get on the network. In actuality, the *@host option is completely against the intentions of using a Z-line, and therefore some IRCd programs will not allow anything other than *@IP, with wildcards (?,*) or CIDR prefix lengths (e.g. /8) allowed in the IP section to block entire subnets. Another difference from K-lines (which affect only IRC clients) is if an IP is banned, nothing, not even other servers, can connect from this IP (or IP range, depending on the banmask).

One advantage to using Z-lines over K-lines and G-lines, from a server or network administrator's perspective, a Z-line uses less bandwidth than a K-line, mainly because it doesn't wait for an ident response or DNS lookup.

A disadvantage to using Z-line over K-line or G-line is that it becomes more difficult to ban entire ISPs and very dynamic IP addresses, common with some dialup and DSL connections. For example, if a network administrator wants to ban all of ISP example.com (with hypothetical IP address ranges of 68.0.0.0 – 68.255.255.255 and 37.0.0.0 – 38.255.255.255), a G-line could use *@*example.com, whereas Z-line would require *@37.*.*.*, *@38.*.*.*, and *@68.*.*.* to accomplish the same thing.

Z-lines can also be global, in which case they are called GZ-lines. GZ-lines work in the same manner as Z-lines, except that they propagate to every server on the network. Some IRC daemons may also be configured to share Z-lines with other servers.

Q-line

"Q-line" redirects here. For the New York City subway service, see Q (New York City Subway service). For the Detroit streetcar service, see QLine.On some IRCds, such as UnrealIRCd, a Q-line forbids a nickname, or any nickname matching a given pattern. This is most often used to forbid use of services nicknames (such as "X", or NickServ) or forbid use of IRC operator nicknames by non-operators. Some IRC daemons may disconnect users when initially applying the Q-line, whilst others will force a nickname change, or do nothing until the user covered by the Q-line reconnects. Other IRCds, like ircd-hybrid, use the "RESV" ("reserve") command instead, with the stats letter remaining as Q. The "RESV" command can also forbid a channel from being used.

See also

References

- Kalt, C. (2000). "RFC 2810 - Internet Relay Chat: Architecture". Tools.ietf.org. doi:10.17487/RFC2810. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - IRC Server Request FAQ Archived 2009-04-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Kalt, C. (2000). "RFC 2810 – Internet Relay Chat: Architecture". Tools.ietf.org. doi:10.17487/RFC2810. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Oikarinen, J.; Reed, D. (1993). "RFC 1459 – Internet Relay Chat Protocol". Tools.ietf.org. doi:10.17487/RFC1459. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Oikarinen, J.; Reed, D. (1993). "RFC 1459 – Internet Relay Chat Protocol". Tools.ietf.org. doi:10.17487/RFC1459. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - IRCD FAQ on irc.org

- "Search IRC, IRCD version overview". Searchirc.com. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- "Open Directory – Computers: Software: Internet: Servers: Chat: IRC". Dmoz.org. 2010-02-26. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- "IRCD – the server". Funet.fi. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- IRC History on IRC.org

- History of IRC, Daniel Stenberg

- Ithildin IRCd

- Inspire IRCd

- "WebMaster Inc". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- "WeIRCd". Archived from the original on 2010-05-14. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- OfficeIRC – IRC Server Software, Web Chat, Internal Communications and Instant Messaging (IM)

- Blog entry mentioning RFC violations

- Numerics diversity of different IRC daemons

- Client source (DMDirc) showing conditions for different servers (e.g. in function starting at line 1523)

- IANA.org

- Oikarinen, J.; Reed, D. (1993). "RFC 1459 – Internet Relay Chat Protocol". Tools.ietf.org. doi:10.17487/RFC1459. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "STARTTLS standard". Archived from the original on 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ^ Paul Mutton, IRC hacks, O'Reilly Media, 2004, ISBN 0-596-00687-X, pp. 371

- beware's P10 documentation

- ircu P10 documentation

- "Reply to thread "K-lined for attemting [sic] to join juped channel ?" on EFnet forums". Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- "Freenode, Using the network". Archived from the original on 2007-02-26. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- IRC Operator Version 1.1.2

External links

- irc.org – IRC resources

- Technical comparison of TS and nickname delay mechanisms

- DarkFire IRC Manual (network specific)

- Undernet K-Line and G-Line FAQ Archived 2008-04-01 at the Wayback Machine with reasons for them, amongst other things

- EFnet FAQ with several -line terms explained

- Quakenet General FAQ G/K-Line

- GLine, KLine, QLine and ELine syntax

| Internet Relay Chat (IRC) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common terms | |||||||||||||||||

| Related protocols | |||||||||||||||||

| Networks | |||||||||||||||||

| Technology | |||||||||||||||||

| See also | |||||||||||||||||

| Clients |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Category | |||||||||||||||||