| Klinefelter syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | XXY syndrome, Klinefelter's syndrome, Klinefelter-Reifenstein-Albright syndrome |

| |

| 47,XXY karyotype | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

| Symptoms | Varied; include above average height, weaker muscles, poor coordination, less body hair, breast growth, small testicle size, less interest in sex, infertility |

| Complications | Infertility, intellectual disability, autoimmune disorders, breast cancer, venous thromboembolic disease, osteoporosis |

| Usual onset | At fertilisation |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | Nondisjunction during gametogenesis or in a zygote |

| Risk factors | Older age of mother |

| Diagnostic method | Genetic testing (karyotype) |

| Prevention | None |

| Treatment | Physical therapy, speech and language therapy, Testosterone Supplementation, counseling |

| Prognosis | Nearly normal life expectancy |

| Frequency | 1 in 500–1000 |

| Named after | Harry Klinefelter |

Klinefelter syndrome (KS), also known as 47,XXY, is a chromosome anomaly where a male has an extra X chromosome. These complications commonly include infertility and small, poorly functioning testicles (if present). These symptoms are often noticed only at puberty, although this is one of the most common chromosomal disorders, occurring in one to two per 1,000 live births. It is named after American endocrinologist Harry Klinefelter, who identified the condition in the 1940s, along with his colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The syndrome is defined by the presence of at least one extra X chromosome in addition to a Y chromosome, yielding a total of 47 or more chromosomes rather than the usual 46. Klinefelter syndrome occurs randomly. The extra X chromosome comes from the father and mother nearly equally. An older mother may have a slightly increased risk of a child with KS. The syndrome is diagnosed by the genetic test known as karyotyping.

Signs and symptoms

A person with typical untreated Klinefelter 46,XY/47,XXY mosaic, diagnosed at age 19 – a scar from biopsy is on his right breast above the nipple.

A person with typical untreated Klinefelter 46,XY/47,XXY mosaic, diagnosed at age 19 – a scar from biopsy is on his right breast above the nipple.

Klinefelter syndrome has different manifestations and these will vary from one patient to another. Among the primary features are infertility and small, poorly functioning testicles. Often, symptoms may be subtle and many people do not realize they are affected. In other cases, symptoms are more prominent and may include weaker muscles, greater height, poor motor coordination, less body hair, gynecomastia (breast growth), and low libido. In the majority of the cases, these symptoms are noticed only at puberty.

Prenatal

Chromosomal abnormalities, including Klinefelter syndrome, are the most common cause of spontaneous abortion. Generally, the severity of the malformations is proportional to the number of extra X chromosomes present in the karyotype. For example, patients with 49 chromosomes (XXXXY) have a lower IQ and more severe physical manifestations than those with 48 chromosomes (XXXY).

Physical manifestations

As babies and children, those with XXY chromosomes may have lower muscle tone and reduced strength. They may sit up, crawl, and walk later than other infants. An average KS child will start walking at 19 months of age. They may also have less muscle control and coordination than other children of their age.

During puberty, KS subjects show less muscular body, less facial and body hair, and broader hips as a consequence of low levels of testosterone. Delays in motor development may occur, which can be addressed through occupational and physical therapies. As teens, males with XXY may develop breast tissue, have weaker bones, and a lower energy level than others. Testicles are affected and are usually less than 2 cm in length (and always shorter than 3.5 cm), 1 cm in width, and 4ml in volume. Those with XXY chromosomes may also have microorchidism (i.e., small testicles).

By adulthood, individuals with KS tend to become taller than average, with proportionally longer arms and legs, less-muscular bodies, more belly fat, wider hips, narrower shoulders. Some will show little to no symptomology, a lanky, youthful build and facial appearance, or a rounded body type. Gynecomastia (increased breast tissue) in males is common, affecting up to 80% of cases. Approximately 10% of males with XXY chromosomes have gynecomastia noticeable enough that they may choose to have surgery.

Individuals with KS are often infertile or have reduced fertility. Advanced reproductive assistance is sometimes possible in order to produce an offspring since approximately 50% of males with Klinefelter syndrome can produce sperm.

Psychological characteristics

Cognitive development

Some degree of language learning or reading impairment may be present, and neuropsychological testing often reveals deficits in executive functions, although these deficits can often be overcome through early intervention. It is estimated that 10% of those with Klinefelter syndrome are autistic. Additional abnormalities may include impaired attention, reduced organizational and planning abilities, deficiencies in judgment (often presented as a tendency to interpret non-threatening stimuli as threatening), and dysfunctional decision processing.

The overall IQ tends to be lower than average. Language milestones may also be delayed, particularly when compared to other people their age. Between 25% and 85% of males with XXY have some kind of language problem, such as delay in learning to speak, trouble using language to express thoughts and needs, problems reading, and trouble processing what they hear. They may also have a harder time doing work that involves reading and writing, but most hold jobs and have successful careers.

Behavior and personality traits

Compared to individuals with a normal number of chromosomes, males affected by Klinefelter syndrome may display behavioral differences. These are phenotypically displayed as higher levels of anxiety and depression, mood dysregulation, impaired social skills, emotional immaturity during childhood, and low frustration tolerance. These neurocognitive disabilities are most likely due to the presence of the extra X chromosome, as indicated by studies carried out on animal models carrying an extra X chromosome.

In 1995, a scientific study evaluated the psychosocial adaptation of 39 adolescents with sex chromosome abnormalities. It demonstrated that males with XXY tend to be quiet, shy and undemanding; they are less self-confident, less active, and more helpful and obedient than other children their age. They may struggle in school and sports, meaning they may have more trouble "fitting in" with other kids.

As adults, they live lives similar to others without the condition; they have friends, families, and normal social relationships. Nonetheless, some individuals may experience social and emotional problems due to problems in childhood. They show a lower sex drive and low self-esteem, in most cases due to their feminine physical characteristics.

Concomitant illness

Those with XXY are more likely than others to have certain health problems, such as autoimmune disorders, breast cancer, venous thromboembolic disease, and osteoporosis. Nonetheless, the risk of breast cancer is still below the normal risk for women. These patients are also more prone to develop cardiovascular disease due to the predominance of metabolic abnormalities such as dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes. It has not been demonstrated that hypertension is related with KS.

In contrast to these potentially increased risks, rare X-linked recessive conditions are thought to occur less frequently in those with XXY than in those without, since these conditions are transmitted by genes on the X chromosome, and people with two X chromosomes are typically only carriers rather than affected by these X-linked recessive conditions.

Cause

Klinefelter syndrome is not an inherited condition. The extra X chromosome comes from the mother in approximately 50% of the cases. Maternal age is the only known risk factor. Women at 40 years have a four-times-higher risk of a child with Klinefelter syndrome than women aged 24 years.

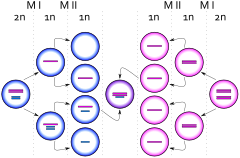

The extra chromosome is retained because of a nondisjunction event during paternal meiosis I, maternal meiosis I, or maternal meiosis II, also known as gametogenesis. The relevant nondisjunction in meiosis I occurs when homologous chromosomes, in this case the X and Y or two X sex chromosomes, fail to separate, producing a sperm with an X and a Y chromosome or an egg with two X chromosomes. Fertilizing a normal (X) egg with this sperm produces an XXY or Klinefelter offspring. Fertilizing a double X egg with a normal sperm also produces an XXY or Klinefelter offspring.

Another mechanism for retaining the extra chromosome is through a nondisjunction event during meiosis II in the egg. Nondisjunction occurs when sister chromatids on the sex chromosome, in this case an X and an X, fail to separate. An XX egg is produced, which when fertilized with a Y sperm, yields an XXY offspring. This XXY chromosome arrangement is one of the most common genetic variations from the XY karyotype, occurring in approximately one in 500 live male births.

In mammals with more than one X chromosome, the genes on all but one X chromosome are not expressed; this is known as X inactivation. This happens in XXY males, as well as normal XX females. However, in XXY males, a few genes located in the pseudoautosomal regions of their X chromosomes have corresponding genes on their Y chromosome and are capable of being expressed.

Variations

The condition 48,XXYY or 48,XXXY occurs in one in 18,000–50,000 male births. The incidence of 49,XXXXY is one in 85,000 to 100,000 male births. These variations are extremely rare. Additional chromosomal material can contribute to cardiac, neurological, orthopedic, urinogenital and other anomalies. Thirteen cases of individuals with a 47,XXY karyotype and a female phenotype have been described.

Mosaicism

Approximately 15–20% of males with KS may have a mosaic 47,XXY/46,XY constitutional karyotype and varying degrees of spermatogenic failure. Often, symptoms are milder in mosaic cases, with regular male secondary sex characteristics and testicular volume even falling within typical adult ranges. Another possible mosaicism is 47,XXY/46,XX with clinical features suggestive of KS and male phenotype, but this is very rare. Thus far, only approximately 10 cases of 47,XXY/46,XX have been described in literature.

Random versus skewed X-inactivation

Main article: X-inactivationWomen typically have two X chromosomes, with half of their X chromosomes switching off early in embryonic development. The same happens with people with Klinefelter's, including in both cases a small proportion of individuals with a skewed ratio between the two Xs.

Pathogenesis

The term "hypogonadism" in XXY symptoms is often misinterpreted to mean "small testicles", when it instead means decreased testicular hormone/endocrine function. Because of (primary) hypogonadism, individuals often have a low serum testosterone level, but high serum follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone levels, hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. Despite this misunderstanding of the term, testicular growth is arrested.

Destruction and hyalinization of the seminiferous tubules cause a reduction in the function of Sertoli cells and Leydig cells, leading to decreased production of FSH and testosterone. This results in impaired spermatogenesis and further endocrine dysfunction.

Diagnosis

The standard diagnostic method is the analysis of the chromosomes' karyotype on lymphocytes. A small blood sample is sufficient as test material. In the past, the observation of the Barr body was common practice, as well. To investigate the presence of a possible mosaicism, analysis of the karyotype using cells from the oral mucosa is performed. Physical characteristics of a Klinefelter syndrome can be tall stature, low body hair, and occasionally an enlargement of the breast. Usually, a small testicle volume of 1–5 ml per testicle (standard values: 12–30 ml) occurs. During puberty and adulthood, low testosterone levels with increased levels of the pituitary hormones FSH and LH in the blood can indicate the presence of Klinefelter syndrome. A spermiogram can also be part of the further investigation. Often, an azoospermia is present, or rarely an oligospermia. Furthermore, Klinefelter syndrome can be diagnosed as a coincidental prenatal finding in the context of invasive prenatal diagnosis (amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling). Approximately 10% of KS cases are found by prenatal diagnosis.

The symptoms of KS are often variable, so a karyotype analysis should be ordered when small testes, infertility, gynecomastia, long arms/legs, developmental delay, speech/language deficits, learning disabilities/academic issues, and/or behavioral issues are present in an individual.

Prognosis

The lifespan of individuals with Klinefelter syndrome appears to be reduced by around 2.1 years compared to the general male population. These results are still questioned data, are not absolute, and need further testing.

Treatment

As the genetic variation is irreversible, no causal therapy is available. From the onset of puberty, the existing testosterone deficiency can be compensated by appropriate hormone-replacement therapy. Testosterone preparations are available in the form of syringes, patches, or gel. If gynecomastia is present, the surgical removal of the breast may be considered for psychological benefits and to reduce the risk of breast cancer.

The use of behavioral therapy can mitigate any language disorders, difficulties at school, and socialization. An approach by occupational therapy is useful in children, especially those who have dyspraxia.

Infertility treatment

Methods of reproductive medicine, such as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) with previously conducted testicular sperm extraction (TESE), have led to men with Klinefelter syndrome producing biological offspring. By 2010, over 100 successful pregnancies have been reported using in vitro fertilization technology with surgically removed sperm material from men with KS.

History

The syndrome was named after American endocrinologist Harry Klinefelter, who in 1942 worked with Fuller Albright and E. C. Reifenstein at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, and first described it in the same year. The account given by Klinefelter came to be known as Klinefelter syndrome as his name appeared first on the published paper, and seminiferous tubule dysgenesis was no longer used. Considering the names of all three researchers, it is sometimes also called Klinefelter–Reifenstein–Albright syndrome. In 1956, Klinefelter syndrome was found to result from an extra chromosome. Plunkett and Barr found the sex chromatin body in cell nuclei of the body. This was further clarified as XXY in 1959 by Patricia Jacobs and John Anderson Strong. The first published report of a man with a 47,XXY karyotype was by Patricia Jacobs and John Strong at Western General Hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1959. This karyotype was found in a 24-year-old man who had signs of KS. Jacobs described her discovery of this first reported human or mammalian chromosome aneuploidy in her 1981 William Allan Memorial Award address.

Klinefelter syndrome has been identified in ancient burials. In August 2022, a team of scientists published a study of a skeleton found in Bragança, north-eastern Portugal, of a man who died around 1000 AD and was discovered by their investigations to have a 47,XXY karyotype. In 2021, bioarchaeological investigation of the individual buried with the Suontaka sword, previously assumed to be a woman, concluded that person "whose gender identity may well have been non-binary", had Klinefelter syndrome.

Cultural and social impacts

In many societies, the symptoms of Klinefelter syndrome have contributed to significant social stigma, particularly due to infertility and gynecomastia. Historically, these traits were often associated with a perceived lack of masculinity, which could result in social ostracism. However, in recent years, increased awareness and advocacy have led to a reduction in stigma, with individuals diagnosed with KS more likely to receive proper medical care and support. Advocacy organizations, such as the American Association for Klinefelter Syndrome Information and Support (AAKSIS), have played a crucial role in promoting understanding and improving the quality of life for affected individuals.

Epidemiology

This syndrome, evenly distributed in all ethnic groups, has a prevalence of approximately four subjects per every 10,000 (0.04%) males in the general population. However, it is estimated that only 25% of the individuals with Klinefelter syndrome are diagnosed throughout their lives. The rate of Klinefelter syndrome among infertile males is 3.1%. The syndrome is the main cause of male hypogonadism. One survey in the United Kingdom found that the majority of people with KS identify as male, however, a significant number have a different gender identity. The prevalence of KS is higher than expected in transgender women.

See also

- Sex chromosome anomalies

- Aneuploidy

- Intersex

- Taurodontism

- Trisomy X

- Turner syndrome

- XYY syndrome

- XXYY syndrome

References

- "What are common symptoms of Klinefelter syndrome (KS)?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 25 October 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Simonetti L, Ferreira LG, Vidi AC, de Souza JS, Kunii IS, Melaragno MI, et al. (2021). "Intelligence Quotient Variability in Klinefelter Syndrome Is Associated With GTPBP6 Expression Under Regulation of X-Chromosome Inactivation Pattern". Frontiers in Genetics. 12: 724625. doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.724625. PMC 8488338. PMID 34616429.

- "Klinefelter syndrome". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Visootsak J, Graham JM (October 2006). "Klinefelter syndrome and other sex chromosomal aneuploidies". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 1: 42. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-1-42. PMC 1634840. PMID 17062147.

- ^ "How many people are affected by or at risk for Klinefelter syndrome (KS)?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 30 November 2012. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "How do health care providers diagnose Klinefelter syndrome (KS)?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2012-11-30. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- "What are the treatments for symptoms in Klinefelter syndrome (KS)". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2013-10-25. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- "Is there a cure for Klinefelter syndrome (KS)?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 30 November 2012. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- "Klinefelter syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. National Library of Medicine. 30 October 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- "Klinefelter syndrome". National Health Service. 20 February 2023. Archived from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Klinefelter, Harry Fitch Jr. (September 1986). "Klinefelter's syndrome: historical background and development". Southern Medical Journal. 79 (9): 1089–1093. doi:10.1097/00007611-198609000-00012. PMID 3529433.

- Visootsak, Jeannie; Graham, John M (2006-10-24). "Klinefelter syndrome and other sex chromosomal aneuploidies". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 1 (1): 42. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-1-42. ISSN 1750-1172. PMC 1634840. PMID 17062147.

- ^ "Klinefelter Syndrome". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Kanakis, George A.; Nieschlag, Eberhard (September 2018). "Klinefelter syndrome: more than hypogonadism". Metabolism. 86: 135–144. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2017.09.017. PMID 29382506. S2CID 3702209.

- "Klinefelter Syndrome (KS): Overview". nichd.nih.gov. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2013-11-15. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Puscheck, Elizabeth (June 16, 2023). "Early Pregnancy Loss". Medscape. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- Defendi GL (January 31, 2022). Rohena LO (ed.). "Klinefelter Syndrome". Medscape. Drugs & Diseases: Pediatrics: Genetics and Metabolic Disease.

- ^ "Klinefelter Syndrome". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 24 May 2007. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- Zierler-Browm SL (August 25, 2006). "Klinefelter's Syndrome: XXY Males". U.S. Pharmacist. 8. West Palm Beach, Florida: 43–51.

- Raheem, Amr Abdel (February 12, 2021). "The Impact and Management of Gynaecomastia in Klinefelter Syndrome". Frontiers in Reproductive Health. 3. doi:10.3389/frph.2021.629673. PMC 9580767. PMID 36303983.

- Denschlag D, Tempfer C, Kunze M, Wolff G, Keck C (October 2004). "Assisted reproductive techniques in patients with Klinefelter syndrome: a critical review". Fertility and Sterility. 82 (4): 875–879. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.09.085. PMID 15482743.

- Graham JM, Bashir AS, Stark RE, Silbert A, Walzer S (June 1988). "Oral and written language abilities of XXY boys: implications for anticipatory guidance". Pediatrics. 81 (6): 795–806. doi:10.1542/peds.81.6.795. PMID 3368277. S2CID 26098458.

- Boone KB, Swerdloff RS, Miller BL, Geschwind DH, Razani J, Lee A, et al. (May 2001). "Neuropsychological profiles of adults with Klinefelter syndrome". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 7 (4): 446–456. doi:10.1017/S1355617701744013. PMID 11396547. S2CID 145642384.

- ^ GenePool (October 17, 2005). "Klinefelter syndrome". Clinical Genetics Specialist Library. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- Skakkebæk A, Moore PJ, Pedersen AD, Bojesen A, Kristensen MK, Fedder J, et al. (November 9, 2018). "Anxiety and depression in Klinefelter syndrome: The impact of personality and social engagement". PLOS ONE. 13 (11): e0206932. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1306932S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206932. PMC 6226182. PMID 30412595.

- Skakkebæk A, Moore PJ, Pedersen AD, Bojesen A, Kristensen MK, Fedder J, et al. (March 2017). "The role of genes, intelligence, personality, and social engagement in cognitive performance in Klinefelter syndrome". Brain and Behavior. 7 (3): e00645. doi:10.1002/brb3.645. PMC 5346527. PMID 28293480.

- de Vries AL, Roehle R, Marshall L, Frisén L, van de Grift TC, Kreukels BP, et al. (September 2019). "Mental Health of a Large Group of Adults With Disorders of Sex Development in Six European Countries". Psychosomatic Medicine. 81 (7): 629–640. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000718. PMC 6727927. PMID 31232913.

- Conn PM (2013). Animal models for the study of human disease (First ed.). San Diego: Elsevier Science & Technology Books. p. 780. doi:10.1016/C2011-0-05225-0. ISBN 9780124159129. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- Bender BG, Harmon RJ, Linden MG, Robinson A (August 1995). "Psychosocial adaptation of 39 adolescents with sex chromosome abnormalities". Pediatrics. 96 (2 Pt 1): 302–308. doi:10.1542/peds.96.2.302. PMID 7630689. S2CID 36072015.

- Hultborn R, Hanson C, Köpf I, Verbiené I, Warnhammar E, Weimarck A (1997). "Prevalence of Klinefelter's syndrome in male breast cancer patients". Anticancer Research. 17 (6D): 4293–4297. PMID 9494523.

- Salzano A, Arcopinto M, Marra AM, Bobbio E, Esposito D, Accardo G, et al. (July 2016). "Klinefelter syndrome, cardiovascular system, and thromboembolic disease: review of literature and clinical perspectives". European Journal of Endocrinology. 175 (1): R27 – R40. doi:10.1530/EJE-15-1025. PMID 26850445.

- ^ Nieschlag E (May 2013). "Klinefelter syndrome: the commonest form of hypogonadism, but often overlooked or untreated". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 110 (20): 347–353. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2013.0347. PMC 3674537. PMID 23825486.

- Gravholt CH, Chang S, Wallentin M, Fedder J, Moore P, Skakkebæk A (August 2018). "Klinefelter Syndrome: Integrating Genetics, Neuropsychology, and Endocrinology". Endocrine Reviews. 39 (4): 389–423. doi:10.1210/er.2017-00212. PMID 29438472.

- ^ "Klinefelter Syndrome – Inheritance Pattern". Medline Plus. NIH. July 10, 2023. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ Bojesen A, Juul S, Gravholt CH (February 2003). "Prenatal and postnatal prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome: a national registry study". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 88 (2): 622–626. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021491. PMID 12574191.

- ^ Tüttelmann F, Gromoll J (June 2010). "Novel genetic aspects of Klinefelter's syndrome". Molecular Human Reproduction. 16 (6): 386–395. doi:10.1093/molehr/gaq019. PMID 20228051.

- Chow JC, Yen Z, Ziesche SM, Brown CJ (2005-09-01). "Silencing of the mammalian X chromosome". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 6 (1): 69–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162350. PMID 16124854.

- Blaschke RJ, Rappold G (June 2006). "The pseudoautosomal regions, SHOX and disease". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. Genetics of disease. 16 (3): 233–239. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.004. PMID 16650979.

- Linden MG, Bender BG, Robinson A (October 1995). "Sex chromosome tetrasomy and pentasomy". Pediatrics. 96 (4 Pt 1): 672–682. doi:10.1542/peds.96.4.672. PMID 7567329.

- Frühmesser, A.; Kotzot, D. (29 April 2011). "Chromosomal Variants in Klinefelter Syndrome". Sexual Development. 5 (3): 109–123. doi:10.1159/000327324. PMID 21540567. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Samplaski MK, Lo KC, Grober ED, Millar A, Dimitromanolakis A, Jarvi KA (April 2014). "Phenotypic differences in mosaic Klinefelter patients as compared with non-mosaic Klinefelter patients". Fertility and Sterility. 101 (4): 950–955. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.051. PMID 24502895. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Velissariou V, Christopoulou S, Karadimas C, Pihos I, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, Kapranos N, et al. (2006). "Rare XXY/XX mosaicism in a phenotypic male with Klinefelter syndrome: case report". European Journal of Medical Genetics. 49 (4): 331–337. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2005.09.001. PMID 16829354.

- Kinjo K, Yoshida T, Kobori Y, Okada H, Suzuki E, Ogata T, Miyado M, Fukami M (January 2020). "Random X chromosome inactivation in patients with Klinefelter syndrome". Molecular and Cellular Pediatrics. 7 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s40348-020-0093-x. PMC 6979883. PMID 31974854.

- ^ Leask K (October 2005). "Klinefelter syndrome". National Library for Health, Specialist Libraries, Clinical Genetics. National Library for Health. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

- Samplaski MK, Lo KC, Grober ED, Millar A, Dimitromanolakis A, Jarvi KA (2014). "Phenotypic differences in mosaic Klinefelter patients as compared with non-mosaic Klinefelter patients". Fertility and Sterility. 101 (4): 950–955. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.051. PMID 24502895.

- Kamischke A, Baumgardt A, Horst J, Nieschlag E (Jan–Feb 2003). "Clinical and diagnostic features of patients with suspected Klinefelter syndrome". Journal of Andrology. 24 (1): 41–48. doi:10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02638.x. PMID 12514081. S2CID 25133531.

- Abramsky L, Chapple J (April 1997). "47,XXY (Klinefelter syndrome) and 47,XYY: estimated rates of and indication for postnatal diagnosis with implications for prenatal counselling". Prenatal Diagnosis. 17 (4): 363–368. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199704)17:4<363::AID-PD79>3.0.CO;2-O. PMID 9160389. S2CID 25935518.

- Bojesen A, Juul S, Birkebaek N, Gravholt CH (August 2004). "Increased mortality in Klinefelter syndrome". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 89 (8): 3830–3834. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0777. PMID 15292313.

- Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, Schoemaker MJ, Wright AF, Jacobs PA (December 2005). "Mortality in patients with Klinefelter syndrome in Britain: a cohort study". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 90 (12): 6516–6522. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1077. PMID 16204366.

- ^ Groth KA, Skakkebæk A, Høst C, Gravholt CH, Bojesen A (January 2013). "Clinical review: Klinefelter syndrome--a clinical update". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 98 (1): 20–30. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-2382. PMID 23118429.

- Gabriele R, Borghese M, Conte M, Egidi F (2002). "". Il Giornale di Chirurgia (in Italian). 23 (6–7): 250–252. PMID 12422780.

- "What are the treatments for symptoms in Klinefelter syndrome (KS)?". nichd.nih.gov/. December 2016. Archived from the original on 2020-07-09. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- Harold Chen. "Klinefelter Syndrome – Treatment". medscape.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- Corona G, Pizzocaro A, Lanfranco F, Garolla A, Pelliccione F, Vignozzi L, et al. (May 2017). "Sperm recovery and ICSI outcomes in Klinefelter syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 23 (3): 265–275. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmx008. hdl:2318/1633550. PMID 28379559.

- Fullerton G, Hamilton M, Maheshwari A (March 2010). "Should non-mosaic Klinefelter syndrome men be labelled as infertile in 2009?". Human Reproduction. 25 (3): 588–597. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep431. PMID 20085911.

- Klinefelter Jr HF, Reifenstein Jr EC, Albright Jr F (1942). "Syndrome characterized by gynecomastia, aspermatogenesis without a-Leydigism and increased excretion of follicle-stimulating hormone". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2 (11): 615–624. doi:10.1210/jcem-2-11-615.

- "The Klinefelter-Reifenstein-Albright syndrome". Biomedsearch.com. Archived from the original on 2017-08-27. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Odom SL (2009). Handbook of developmental disabilities (Pbk. ed.). New York: Guilford. p. 113. ISBN 9781606232484. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10. Retrieved 2017-09-02.

- ^ Jacobs PA, Strong JA (January 1959). "A case of human intersexuality having a possible XXY sex-determining mechanism". Nature. 183 (4657): 302–303. Bibcode:1959Natur.183..302J. doi:10.1038/183302a0. PMID 13632697. S2CID 38349997.

- Jacobs PA (September 1982). "The William Allan Memorial Award address: human population cytogenetics: the first twenty-five years". American Journal of Human Genetics. 34 (5): 689–698. PMC 1685430. PMID 6751075.

- Roca-Rada X, Tereso S, Rohrlach AB, Brito A, Williams MP, Umbelino C, et al. (August 2022). "A 1000-year-old case of Klinefelter's syndrome diagnosed by integrating morphology, osteology, and genetics". Lancet. 400 (10353): 691–692. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01476-3. hdl:10316/101524. PMID 36030812. S2CID 251817711.

- Moilanen U, Kirkinen T, Saari NJ, Rohrlach AB, Krause J, Onkamo P, Salmela E (2021-07-15). "A Woman with a Sword? – Weapon Grave at Suontaka Vesitorninmäki, Finland". European Journal of Archaeology. 25. Cambridge University Press: 42–60. doi:10.1017/eaa.2021.30. hdl:10138/340641. ISSN 1461-9571.

- Robinson, Arthur; Bender, Bruce G.; Linden, Mary G. (1992). "Prognosis of prenatally diagnosed children with sex chromosome aneuploidy". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 44 (3): 365–368. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320440319. ISSN 0148-7299. PMID 1488987.

- Jacobs PA (1979). "Recurrence risks for chromosome abnormalities". Birth Defects Original Article Series. 15 (5C): 71–80. PMID 526617.

- Maclean N, Harnden DG, Court Brown WM (August 1961). "Abnormalities of sex chromosome constitution in newborn babies". Lancet. 2 (7199): 406–408. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(61)92486-2. PMID 13764957.

- Visootsak J, Aylstock M, Graham JM (December 2001). "Klinefelter syndrome and its variants: an update and review for the primary pediatrician". Clinical Pediatrics. 40 (12): 639–651. doi:10.1177/000992280104001201. PMID 11771918. S2CID 43040200.

- Matlach J, Grehn F, Klink T (Jan 2012). "Klinefelter syndrome associated with goniodysgenesis". Journal of Glaucoma. 22 (5): e7 – e8. doi:10.1097/IJG.0b013e31824477ef. PMID 22274665. S2CID 30565002.

- Cai, Valerie; Yap, Tet (2022). "Gender Identity and Questioning in Klinefelter's Syndrome". BJPsych Open. 8 (S1). Royal College of Psychiatrists: S44 – S45. doi:10.1192/bjo.2022.176. ISSN 2056-4724. PMC 9378311.

- Liang, Bonnie; Cheung, Ada S.; Nolan, Brendan J. (2022-04-15). "Clinical features and prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome in transgender individuals: A systematic review". Clinical Endocrinology. 97 (1). Wiley: 3–12. doi:10.1111/cen.14734. ISSN 0300-0664. PMC 9540025. PMID 35394664.

Further reading

- Cover VI (2012). Living with Klinefelter Syndrome, Trisomy X and 47,XYY: A Guide for Families and Individuals Affected by Extra X and Y Chromosomes (PDF). Virginia Isaacs Cover. ISBN 978-0-615-57400-4.

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |