A Langmuir probe is a device used to determine the electron temperature, electron density, and electric potential of a plasma. It works by inserting one or more electrodes into a plasma, with a constant or time-varying electric potential between the various electrodes or between them and the surrounding vessel. The measured currents and potentials in this system allow the determination of the physical properties of the plasma.

I-V characteristic of the Debye sheath

The beginning of Langmuir probe theory is the I–V characteristic of the Debye sheath, that is, the current density flowing to a surface in a plasma as a function of the voltage drop across the sheath. The analysis presented here indicates how the electron temperature, electron density, and plasma potential can be derived from the I–V characteristic. In some situations a more detailed analysis can yield information on the ion density (), the ion temperature , or the electron energy distribution function (EEDF) or .

Ion saturation current density

Consider first a surface biased to a large negative voltage. If the voltage is large enough, essentially all electrons (and any negative ions) will be repelled. The ion velocity will satisfy the Bohm sheath criterion, which is, strictly speaking, an inequality, but which is usually marginally fulfilled. The Bohm criterion in its marginal form says that the ion velocity at the sheath edge is simply the sound speed given by

.

The ion temperature term is often neglected, which is justified if the ions are cold. Z is the (average) charge state of the ions, and is the adiabatic coefficient for the ions. The proper choice of is a matter of some contention. Most analyses use , corresponding to isothermal ions, but some kinetic theory suggests that . For and , using the larger value results in the conclusion that the density is times smaller. Uncertainties of this magnitude arise several places in the analysis of Langmuir probe data and are very difficult to resolve.

The charge density of the ions depends on the charge state Z, but quasineutrality allows one to write it simply in terms of the electron density as , where is the charge of an electron and is the number density of electrons.

Using these results we have the current density to the surface due to the ions. The current density at large negative voltages is due solely to the ions and, except for possible sheath expansion effects, does not depend on the bias voltage, so it is referred to as the ion saturation current density and is given by

where is as defined above.

The plasma parameters, in particular, the density, are those at the sheath edge.

Exponential electron current

As the voltage of the Debye sheath is reduced, the more energetic electrons are able to overcome the potential barrier of the electrostatic sheath. We can model the electrons at the sheath edge with a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution, i.e.,

,

except that the high energy tail moving away from the surface is missing, because only the lower energy electrons moving toward the surface are reflected. The higher energy electrons overcome the sheath potential and are absorbed. The mean velocity of the electrons which are able to overcome the voltage of the sheath is

,

where the cut-off velocity for the upper integral is

.

is the voltage across the Debye sheath, that is, the potential at the sheath edge minus the potential of the surface. For a large voltage compared to the electron temperature, the result is

.

With this expression, we can write the electron contribution to the current to the probe in terms of the ion saturation current as

,

valid as long as the electron current is not more than two or three times the ion current.

Floating potential

The total current, of course, is the sum of the ion and electron currents:

.

We are using the convention that current from the surface into the plasma is positive. An interesting and practical question is the potential of a surface to which no net current flows. It is easily seen from the above equation that

.

If we introduce the ion reduced mass , we can write

Since the floating potential is the experimentally accessible quantity, the current (below electron saturation) is usually written as

.

Electron saturation current

When the electrode potential is equal to or greater than the plasma potential, then there is no longer a sheath to reflect electrons, and the electron current saturates. Using the Boltzmann expression for the mean electron velocity given above with and setting the ion current to zero, the electron saturation current density would be

Although this is the expression usually given in theoretical discussions of Langmuir probes, the derivation is not rigorous and the experimental basis is weak. The theory of double layers typically employs an expression analogous to the Bohm criterion, but with the roles of electrons and ions reversed, namely

where the numerical value was found by taking Ti=Te and γi=γe.

In practice, it is often difficult and usually considered uninformative to measure the electron saturation current experimentally. When it is measured, it is found to be highly variable and generally much lower (a factor of three or more) than the value given above. Often a clear saturation is not seen at all. Understanding electron saturation is one of the most important outstanding problems of Langmuir probe theory.

Effects of the bulk plasma

The Debye sheath theory explains the basic behavior of Langmuir probes, but is not complete. Merely inserting an object like a probe into a plasma changes the density, temperature, and potential at the sheath edge and perhaps everywhere. Changing the voltage on the probe will also, in general, change various plasma parameters. Such effects are less well understood than sheath physics, but they can at least in some cases be roughly accounted.

Pre-sheath

The Bohm criterion requires the ions to enter the Debye sheath at the sound speed. The potential drop that accelerates them to this speed is called the pre-sheath. It has a spatial scale that depends on the physics of the ion source but which is large compared to the Debye length and often of the order of the plasma dimensions. The magnitude of the potential drop is equal to (at least)

The acceleration of the ions also entails a decrease in the density, usually by a factor of about 2 depending on the details.

Resistivity

Collisions between ions and electrons will also affect the I-V characteristic of a Langmuir probe. When an electrode is biased to any voltage other than the floating potential, the current it draws must pass through the plasma, which has a finite resistivity. The resistivity and current path can be calculated with relative ease in an unmagnetized plasma. In a magnetized plasma, the problem is much more difficult. In either case, the effect is to add a voltage drop proportional to the current drawn, which shears the characteristic. The deviation from an exponential function is usually not possible to observe directly, so that the flattening of the characteristic is usually misinterpreted as a larger plasma temperature. Looking at it from the other side, any measured I-V characteristic can be interpreted as a hot plasma, where most of the voltage is dropped in the Debye sheath, or as a cold plasma, where most of the voltage is dropped in the bulk plasma. Without quantitative modeling of the bulk resistivity, Langmuir probes can only give an upper limit on the electron temperature.

Sheath expansion

It is not enough to know the current density as a function of bias voltage since it is the absolute current which is measured. In an unmagnetized plasma, the current-collecting area is usually taken to be the exposed surface area of the electrode. In a magnetized plasma, the projected area is taken, that is, the area of the electrode as viewed along the magnetic field. If the electrode is not shadowed by a wall or other nearby object, then the area must be doubled to account for current coming along the field from both sides. If the electrode dimensions are not small in comparison to the Debye length, then the size of the electrode is effectively increased in all directions by the sheath thickness. In a magnetized plasma, the electrode is sometimes assumed to be increased in a similar way by the ion Larmor radius.

The finite Larmor radius allows some ions to reach the electrode that would have otherwise gone past it. The details of the effect have not been calculated in a fully self-consistent way.

If we refer to the probe area including these effects as (which may be a function of the bias voltage) and make the assumptions

- ,

- , and

- ,

and ignore the effects of

- bulk resistivity, and

- electron saturation,

then the I-V characteristic becomes

,

where

.

Magnetized plasmas

The theory of Langmuir probes is much more complex when the plasma is magnetized. The simplest extension of the unmagnetized case is simply to use the projected area rather than the surface area of the electrode. For a long cylinder far from other surfaces, this reduces the effective area by a factor of π/2 = 1.57. As mentioned before, it might be necessary to increase the radius by about the thermal ion Larmor radius, but not above the effective area for the unmagnetized case.

The use of the projected area seems to be closely tied with the existence of a magnetic sheath. Its scale is the ion Larmor radius at the sound speed, which is normally between the scales of the Debye sheath and the pre-sheath. The Bohm criterion for ions entering the magnetic sheath applies to the motion along the field, while at the entrance to the Debye sheath it applies to the motion normal to the surface. This results in a reduction of the density by the sine of the angle between the field and the surface. The associated increase in the Debye length must be taken into account when considering ion non-saturation due to sheath effects.

Especially interesting and difficult to understand is the role of cross-field currents. Naively, one would expect the current to be parallel to the magnetic field along a flux tube. In many geometries, this flux tube will end at a surface in a distant part of the device, and this spot should itself exhibit an I-V characteristic. The net result would be the measurement of a double-probe characteristic; in other words, electron saturation current equal to the ion saturation current.

When this picture is considered in detail, it is seen that the flux tube must charge up and the surrounding plasma must spin around it. The current into or out of the flux tube must be associated with a force that slows down this spinning. Candidate forces are viscosity, friction with neutrals, and inertial forces associated with plasma flows, either steady or fluctuating. It is not known which force is strongest in practice, and in fact it is generally difficult to find any force that is powerful enough to explain the characteristics actually measured.

It is also likely that the magnetic field plays a decisive role in determining the level of electron saturation, but no quantitative theory is as yet available.

Electrode configurations

Once one has a theory of the I-V characteristic of an electrode, one can proceed to measure it and then fit the data with the theoretical curve to extract the plasma parameters. The straightforward way to do this is to sweep the voltage on a single electrode, but, for a number of reasons, configurations using multiple electrodes or exploring only a part of the characteristic are used in practice.

Single probe

The most straightforward way to measure the I-V characteristic of a plasma is with a single probe, consisting of one electrode biased with a voltage ramp relative to the vessel. The advantages are simplicity of the electrode and redundancy of information, i.e. one can check whether the I-V characteristic has the expected form. Potentially additional information can be extracted from details of the characteristic. The disadvantages are more complex biasing and measurement electronics and a poor time resolution. If fluctuations are present (as they always are) and the sweep is slower than the fluctuation frequency (as it usually is), then the I-V is the average current as a function of voltage, which may result in systematic errors if it is analyzed as though it were an instantaneous I-V. The ideal situation is to sweep the voltage at a frequency above the fluctuation frequency but still below the ion cyclotron frequency. This, however, requires sophisticated electronics and a great deal of care.

Double probe

An electrode can be biased relative to a second electrode, rather than to the ground. The theory is similar to that of a single probe, except that the current is limited to the ion saturation current for both positive and negative voltages. In particular, if is the voltage applied between two identical electrodes, the current is given by;

,

which can be rewritten using as a hyperbolic tangent:

.

One advantage of the double probe is that neither electrode is ever very far above floating, so the theoretical uncertainties at large electron currents are avoided. If it is desired to sample more of the exponential electron portion of the characteristic, an asymmetric double probe may be used, with one electrode larger than the other. If the ratio of the collection areas is larger than the square root of the ion to electron mass ratio, then this arrangement is equivalent to the single tip probe. If the ratio of collection areas is not that big, then the characteristic will be in-between the symmetric double tip configuration and the single-tip configuration. If is the area of the larger tip then:

Another advantage is that there is no reference to the vessel, so it is to some extent immune to the disturbances in a radio frequency plasma. On the other hand, it shares the limitations of a single probe concerning complicated electronics and poor time resolution. In addition, the second electrode not only complicates the system, but it makes it susceptible to disturbance by gradients in the plasma.

Triple probe

An elegant electrode configuration is the triple probe, consisting of two electrodes biased with a fixed voltage and a third which is floating. The bias voltage is chosen to be a few times the electron temperature so that the negative electrode draws the ion saturation current, which, like the floating potential, is directly measured. A common rule of thumb for this voltage bias is 3/e times the expected electron temperature. Because the biased tip configuration is floating, the positive probe can draw at most an electron current only equal in magnitude and opposite in polarity to the ion saturation current drawn by the negative probe, given by :

and as before the floating tip draws effectively no current:

.

Assuming that: 1.) The electron energy distribution in the plasma is Maxwellian, 2.) The mean free path of the electrons is greater than the ion sheath about the tips and larger than the probe radius, and 3.) the probe sheath sizes are much smaller than the probe separation, then the current to any probe can be considered composed of two parts – the high energy tail of the Maxwellian electron distribution, and the ion saturation current:

where the current Ie is thermal current. Specifically,

,

where S is surface area, Je is electron current density, and ne is electron density.

Assuming that the ion and electron saturation current is the same for each probe, then the formulas for current to each of the probe tips take the form

.

It is then simple to show

but the relations from above specifying that I+=-I− and Ifl=0 give

,

a transcendental equation in terms of applied and measured voltages and the unknown Te that in the limit qeVBias = qe(V+-V−) >> k Te, becomes

.

That is, the voltage difference between the positive and floating electrodes is proportional to the electron temperature. (This was especially important in the sixties and seventies before sophisticated data processing became widely available.)

More sophisticated analysis of triple probe data can take into account such factors as incomplete saturation, non-saturation, unequal areas.

Triple probes have the advantage of simple biasing electronics (no sweeping required), simple data analysis, excellent time resolution, and insensitivity to potential fluctuations (whether imposed by an rf source or inherent fluctuations). Like double probes, they are sensitive to gradients in plasma parameters.

Special arrangements

Arrangements with four (tetra probe) or five (penta probe) have sometimes been used, but the advantage over triple probes has never been entirely convincing. The spacing between probes must be larger than the Debye length of the plasma to prevent an overlapping Debye sheath.

A pin-plate probe consists of a small electrode directly in front of a large electrode, the idea being that the voltage sweep of the large probe can perturb the plasma potential at the sheath edge and thereby aggravate the difficulty of interpreting the I-V characteristic. The floating potential of the small electrode can be used to correct for changes in potential at the sheath edge of the large probe. Experimental results from this arrangement look promising, but experimental complexity and residual difficulties in the interpretation have prevented this configuration from becoming standard.

Various geometries have been proposed for use as ion temperature probes, for example, two cylindrical tips that rotate past each other in a magnetized plasma. Since shadowing effects depend on the ion Larmor radius, the results can be interpreted in terms of ion temperature. The ion temperature is an important quantity that is very difficult to measure. Unfortunately, it is also very difficult to analyze such probes in a fully self-consistent way.

Emissive probes use an electrode heated either electrically or by the exposure to the plasma. When the electrode is biased more positive than the plasma potential, the emitted electrons are pulled back to the surface so the I-V characteristic is hardly changed. As soon as the electrode is biased negative with respect to the plasma potential, the emitted electrons are repelled and contribute a large negative current. The onset of this current or, more sensitively, the onset of a discrepancy between the characteristics of an unheated and a heated electrode, is a sensitive indicator of the plasma potential.

To measure fluctuations in plasma parameters, arrays of electrodes are used, usually one – but occasionally two-dimensional. A typical array has a spacing of 1 mm and a total of 16 or 32 electrodes. A simpler arrangement to measure fluctuations is a negatively biased electrode flanked by two floating electrodes. The ion-saturation current is taken as a surrogate for the density and the floating potential as a surrogate for the plasma potential. This allows a rough measurement of the turbulent particle flux

Cylindrical Langmuir probe in electron flow

Most often, the Langmuir probe is a small sized electrode inserted into a plasma which is connected to an external circuit that measures the properties of the plasma with respect to ground. The ground is typically an electrode with a large surface area and is usually in contact with the same plasma (very often the metallic wall of the chamber). This allows the probe to measure the I-V characteristic of the plasma. The probe measures the characteristic current of the plasma when the probe is biased with a potential .

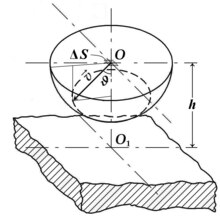

Relations between the probe I-V characteristic and parameters of isotropic plasma were found by Irving Langmuir and they can be derived most elementary for the planar probe of a large surface area (ignoring the edge effects problem). Let us choose the point in plasma at the distance from the probe surface where electric field of the probe is negligible while each electron of plasma passing this point could reach the probe surface without collisions with plasma components: , is the Debye length and is the electron free path calculated for its total cross section with plasma components. In the vicinity of the point we can imagine a small element of the surface area parallel to the probe surface. The elementary current of plasma electrons passing throughout in a direction of the probe surface can be written in the form

| , | 1 |

where is a scalar of the electron thermal velocity vector ,

| , | 2 |

is the element of the solid angle with its relative value , is the angle between perpendicular to the probe surface recalled from the point and the radius-vector of the electron thermal velocity forming a spherical layer of thickness in velocity space, and is the electron distribution function normalized to unity

| . | 3 |

Taking into account uniform conditions along the probe surface (boundaries are excluded), , we can take double integral with respect to the angle , and with respect to the velocity , from the expression (1), after substitution Eq. (2) in it, to calculate a total electron current on the probe

| . | 4 |

where is the probe potential with respect to the potential of plasma , is the lowest electron velocity value at which the electron still could reach the probe surface charged to the potential , is the upper limit of the angle at which the electron having initial velocity can still reach the probe surface with a zero-value of its velocity at this surface. That means the value is defined by the condition

| . | 5 |

Deriving the value from Eq. (5) and substituting it in Eq. (4), we can obtain the probe I-V characteristic (neglecting the ion current) in the range of the probe potential in the form

| . | 6 |

Differentiating Eq. (6) twice with respect to the potential , one can find the expression describing the second derivative of the probe I-V characteristic (obtained firstly by M. J. Druyvestein

| 7 |

defining the electron distribution function over velocity in the evident form. M. J. Druyvestein has shown in particular that Eqs. (6) and (7) are valid for description of operation of the probe of any arbitrary convex geometrical shape. Substituting the Maxwellian distribution function:

| , | 8 |

where is the most probable velocity, in Eq. (6) we obtain the expression

| . | 9 |

From which the very useful in practice relation follows

| . | 10 |

allowing one to derive the electron energy (for Maxwellian distribution function only!) by a slope of the probe I-V characteristic in a semilogarithmic scale. Thus in plasmas with isotropic electron distributions, the electron current on a surface of the cylindrical Langmuir probe at plasma potential is defined by the average electron thermal velocity and can be written down as equation (see Eqs. (6), (9) at )

| , | 11 |

where is the electron concentration, is the probe radius, and is its length. It is obvious that if plasma electrons form an electron wind (flow) across the cylindrical probe axis with a velocity , the expression

| 12 |

holds true. In plasmas produced by gas-discharge arc sources as well as inductively coupled sources, the electron wind can develop the Mach number . Here the parameter is introduced along with the Mach number for simplification of mathematical expressions. Note that , where is the most probable velocity for the Maxwellian distribution function, so that . Thus the general case where is of the theoretical and practical interest. Corresponding physical and mathematical considerations presented in Refs. has shown that at the Maxwellian distribution function of the electrons in a reference system moving with the velocity across axis of the cylindrical probe set at plasma potential , the electron current on the probe can be written down in the form

| , | 13 |

where and are Bessel functions of imaginary arguments and Eq. (13) is reduced to Eq. (11) at being reduced to Eq. (12) at . The second derivative of the probe I-V characteristic with respect to the probe potential can be presented in this case in the form (see Fig. 3)

| , | 14 |

where

| 15 |

and the electron energy is expressed in eV.

All parameters of the electron population: , , and in plasma can be derived from the experimental probe I-V characteristic second derivative by its least square best fitting with the theoretical curve expressed by Eq. (14). For detail and for problem of the general case of none-Maxwellian electron distribution functions see.

Practical considerations

For laboratory and technical plasmas, the electrodes are most commonly tungsten or tantalum wires several thousandths of an inch thick, because they have a high melting point but can be made small enough not to perturb the plasma. Although the melting point is somewhat lower, molybdenum is sometimes used because it is easier to machine and solder than tungsten. For fusion plasmas, graphite electrodes with dimensions from 1 to 10 mm are usually used because they can withstand the highest power loads (also sublimating at high temperatures rather than melting), and result in reduced bremsstrahlung radiation (with respect to metals) due to the low atomic number of carbon. The electrode surface exposed to the plasma must be defined, e.g. by insulating all but the tip of a wire electrode. If there can be significant deposition of conducting materials (metals or graphite), then the insulator should be separated from the electrode by a meander to prevent short-circuiting.

In a magnetized plasma, it appears to be best to choose a probe size a few times larger than the ion Larmor radius. A point of contention is whether it is better to use proud probes, where the angle between the magnetic field and the surface is at least 15°, or flush-mounted probes, which are embedded in the plasma-facing components and generally have an angle of 1 to 5 °. Many plasma physicists feel more comfortable with proud probes, which have a longer tradition and possibly are less perturbed by electron saturation effects, although this is disputed. Flush-mounted probes, on the other hand, being part of the wall, are less perturbative. Knowledge of the field angle is necessary with proud probes to determine the fluxes to the wall, whereas it is necessary with flush-mounted probes to determine the density.

In very hot and dense plasmas, as found in fusion research, it is often necessary to limit the thermal load to the probe by limiting the exposure time. A reciprocating probe is mounted on an arm that is moved into and back out of the plasma, usually in about one second by means of either a pneumatic drive or an electromagnetic drive using the ambient magnetic field. Pop-up probes are similar, but the electrodes rest behind a shield and are only moved the few millimeters necessary to bring them into the plasma near the wall.

A Langmuir probe can be purchased off the shelf for on the order of 15,000 U.S. dollars, or they can be built by an experienced researcher or technician. When working at frequencies under 100 MHz, it is advisable to use blocking filters, and take necessary grounding precautions.

In low temperature plasmas, in which the probe does not get hot, surface contamination may become an issue. This effect can cause hysteresis in the I-V curve and may limit the current collected by the probe. A heating mechanism or a glow discharge plasma may be used to clean the probe and prevent misleading results.

See also

Further reading

- Hopwood, J. (1993). "Langmuir probe measurements of a radio frequency induction plasma". Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology A. 11 (1): 152–156. Bibcode:1993JVST...11..152H. doi:10.1116/1.578282.

- A. Schwabedissen; E. C. Benck; J. R. Roberts (1997). "Langmuir probe measurements in an inductively coupled plasma source". Phys. Rev. E. 55 (3): 3450–3459. Bibcode:1997PhRvE..55.3450S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.55.3450.

References

- Block, L. P. (May 1978). "A Double Layer Review". Astrophysics and Space Science. 55 (1): 59–83. Bibcode:1978Ap&SS..55...59B. doi:10.1007/bf00642580. S2CID 122977170. Retrieved April 16, 2013. (Harvard.edu)

- Sin-Li Chen; T. Sekiguchi (1965). "Instantaneous Direct-Display System of Plasma Parameters by Means of Triple Probe". Journal of Applied Physics. 36 (8): 2363–2375. Bibcode:1965JAP....36.2363C. doi:10.1063/1.1714492.

- Stanojević, M.; Čerček, M.; Gyergyek, T. (1999). "Experimental Study of Planar Langmuir Probe Characteristics in Electron Current-Carrying Magnetized Plasma". Contributions to Plasma Physics. 39 (3): 197–222. Bibcode:1999CoPP...39..197S. doi:10.1002/ctpp.2150390303. S2CID 122406275.

- Mott-Smith, H. M.; Langmuir, Irving (1926). "The Theory of Collectors in Gaseous Discharges". Phys. Rev. 28 (4): 727–763. Bibcode:1926PhRv...28..727M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.28.727.

- Druyvesteyn MJ (1930). "Der Niedervoltbogen". Zeitschrift für Physik. 64 (11–12): 781–798. Bibcode:1930ZPhy...64..781D. doi:10.1007/BF01773007. ISSN 1434-6001. S2CID 186229362.

- E. V. Shun'ko (1990). "V-A characteristic of a cylindrical probe in plasma with electron flow". Physics Letters A. 147 (1): 37–42. Bibcode:1990PhLA..147...37S. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(90)90010-L.

- Shun'ko EV (2009). Langmuir Probe in Theory and Practice. Universal Publishers, Boca Raton, Fl. 2008. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-59942-935-9.

- W. Amatucci; et al. (2001). "Contamination-free sounding rocket Langmuir probe". Review of Scientific Instruments. 72 (4): 2052–2057. Bibcode:2001RScI...72.2052A. doi:10.1063/1.1357234.

), the ion temperature

), the ion temperature  , or the electron energy

, or the electron energy  .

.

.

.

is the adiabatic coefficient for the ions. The proper choice of

is the adiabatic coefficient for the ions. The proper choice of  , corresponding to isothermal ions, but some kinetic theory suggests that

, corresponding to isothermal ions, but some kinetic theory suggests that  . For

. For  and

and  , using the larger value results in the conclusion that the density is

, using the larger value results in the conclusion that the density is  times smaller. Uncertainties of this magnitude arise several places in the analysis of Langmuir probe data and are very difficult to resolve.

times smaller. Uncertainties of this magnitude arise several places in the analysis of Langmuir probe data and are very difficult to resolve.

, where

, where  is the charge of an electron and

is the charge of an electron and  is the number density of electrons.

is the number density of electrons.

where

where  is as defined above.

is as defined above.

,

,

,

,

.

.

is the

is the  .

.

,

,

.

.

.

.

, we can write

, we can write

.

.

and setting the ion current to zero, the electron saturation current density would be

and setting the ion current to zero, the electron saturation current density would be

(which may be a function of the bias voltage) and make the assumptions

(which may be a function of the bias voltage) and make the assumptions

,

, ,

,

.

.

is the voltage applied between two identical electrodes, the current is given by;

is the voltage applied between two identical electrodes, the current is given by;

,

,

as a

as a  .

.

is the area of the larger tip then:

is the area of the larger tip then:

.

.

,

,

.

.

,

,

.

.

of the plasma when the probe is biased with a potential

of the plasma when the probe is biased with a potential  .

.

(ignoring the edge effects problem). Let us choose the point

(ignoring the edge effects problem). Let us choose the point  in plasma at the distance

in plasma at the distance  from the probe surface where electric field of the probe is negligible while each electron of plasma passing this point could reach the probe surface without collisions with plasma components:

from the probe surface where electric field of the probe is negligible while each electron of plasma passing this point could reach the probe surface without collisions with plasma components:  ,

,  is the

is the  is the electron free path calculated for its total

is the electron free path calculated for its total  parallel to the probe surface. The elementary current

parallel to the probe surface. The elementary current  of plasma electrons passing throughout

of plasma electrons passing throughout  ,

, is a scalar of the electron thermal velocity vector

is a scalar of the electron thermal velocity vector  ,

,

,

, is the element of the solid angle with its relative value

is the element of the solid angle with its relative value  ,

,  is the angle between perpendicular to the probe surface recalled from the point

is the angle between perpendicular to the probe surface recalled from the point  in velocity space, and

in velocity space, and  is the electron distribution function normalized to unity

is the electron distribution function normalized to unity

.

. , we can take double integral with respect to the angle

, we can take double integral with respect to the angle  .

. ,

,  is the lowest electron velocity value at which the electron still could reach the probe surface charged to the potential

is the lowest electron velocity value at which the electron still could reach the probe surface charged to the potential  is the upper limit of the angle

is the upper limit of the angle  .

.  in the form

in the form

.

.

in the evident form. M. J. Druyvestein has shown in particular that Eqs. (

in the evident form. M. J. Druyvestein has shown in particular that Eqs. ( ,

, is the most probable velocity, in Eq. (

is the most probable velocity, in Eq. ( .

. .

. (for

(for  on a surface

on a surface  of the cylindrical Langmuir probe at plasma potential

of the cylindrical Langmuir probe at plasma potential  and can be written down as equation (see Eqs. (

and can be written down as equation (see Eqs. ( ,

, is the electron concentration,

is the electron concentration,  is the probe radius, and

is the probe radius, and  is its length.

It is obvious that if plasma electrons form an electron wind (flow) across the cylindrical probe axis with a velocity

is its length.

It is obvious that if plasma electrons form an electron wind (flow) across the cylindrical probe axis with a velocity  , the expression

, the expression

. Here the parameter

. Here the parameter  is introduced along with the Mach number for simplification of mathematical expressions. Note that

is introduced along with the Mach number for simplification of mathematical expressions. Note that  , where

, where is the most probable velocity for the

is the most probable velocity for the  . Thus the general case where

. Thus the general case where  is of the theoretical and practical interest.

Corresponding physical and mathematical considerations presented in Refs. has shown that at the

is of the theoretical and practical interest.

Corresponding physical and mathematical considerations presented in Refs. has shown that at the  across axis of the cylindrical probe set at plasma potential

across axis of the cylindrical probe set at plasma potential  ,

, and

and  are Bessel functions of imaginary arguments and Eq. (

are Bessel functions of imaginary arguments and Eq. ( being reduced to Eq. (

being reduced to Eq. ( .

The second derivative of the probe I-V characteristic

.

The second derivative of the probe I-V characteristic  with respect to the probe potential

with respect to the probe potential  ,

,

is expressed in eV.

is expressed in eV.