Malay was first used in the first millennia known as Old Malay, a part of the Austronesian language family. Over a period of two millennia, Malay has undergone various stages of development that derived from different layers of foreign influences through international trade, religious expansion, colonisation and developments of new socio-political trends. The oldest form of Malay is descended from the Proto-Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by the earliest Austronesian settlers in Southeast Asia. This form would later evolve into Old Malay when Indian cultures and religions began penetrating the region, most probably using the Kawi and Rencong scripts, some linguistic researchers say. Old Malay contained some terms that exist today, but are unintelligible to modern speakers, while the modern language is already largely recognisable in written Classical Malay of 1303 CE.

Malay evolved extensively into Classical Malay through the gradual influx of numerous elements of Arabic and Persian vocabulary when Islam made its way to the region. Initially, Classical Malay was a diverse group of dialects, reflecting the varied origins of the Malay kingdoms of Southeast Asia. One of these dialects that was developed in the literary tradition of Malacca in the 15th century, eventually became predominant. The strong influence of Malacca in international trade in the region resulted in Malay as a lingua franca in commerce and diplomacy, a status that it maintained throughout the age of the succeeding Malay sultanates, the European colonial era and the modern times. From the 19th to 20th century, Malay evolved progressively through significant grammatical improvements and lexical enrichment into a modern language with more than 800,000 phrases in various disciplines.

Proto-Malayic

Main article: Proto-Malayic languageProto-Malayic is the language believed to have existed in prehistoric times, spoken by the early Austronesian settlers in the region. Its ancestor, the Proto-Malayo-Polynesian language that derived from Proto-Austronesian, began to break up by at least 2000 BCE as a result possibly by the southward expansion of Austronesian peoples into the Philippines, Borneo, Maluku and Sulawesi from the island of Taiwan. The Proto-Malayic language was spoken in Borneo at least by 1000 BCE and was, it has been argued, the ancestral language of all subsequent Malay dialects. Linguists generally agree that the homeland of the Malayic languages is in Borneo, based on its geographic spread in the interior, its variations that are not due to contact-induced change, and its sometimes conservative character. Around the beginning of the first millennium, Malayic speakers had established settlements in the coastal regions of modern-day Sumatra, Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Luzon, Sulawesi, Maluku Islands, Riau Islands, Bangka-Belitung Islands and Java-Bali Islands.

Old Malay (3rd to 14th century)

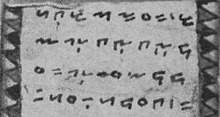

The beginning of the common era saw the growing influence of Indian civilisation in the archipelago. With the penetration and proliferation of Sanskrit vocabulary and the influence of major Indian religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism, Ancient Malay evolved into the Old Malay. The oldest uncontroversial specimens of Old Malay are the 7th century CE Sojomerto inscription from Central Java, Kedukan Bukit Inscription from South Sumatra, Indonesia and several other inscriptions dating from the 7th to 10th centuries discovered in Sumatra, Java, other islands of the Sunda archipelago, as well as Luzon, Philippines. All these Old Malay inscriptions used either scripts of Indian origin such as Pallava, Nagari or the Indian-influenced old Sumatran characters.

The Old Malay system is greatly influenced by Sanskrit scriptures in terms of phonemes, morphemes, vocabulary and the characteristics of scholarship, particularly when the words are closely related to Indian culture such as puja, bakti, kesatria, maharaja and raja, as well as on the Hindu-Buddhist religion such as dosa, pahala, neraka, syurga or surga (used in Indonesia-which was based on Malay), puasa, sami and biara, which lasts until today. In fact, some Malays regardless of personal religion have names derived from Sanskrit such as the names of Indian Hindu gods or heroes include Puteri/Putri, Putera/Putra, Wira and Wati.

It is popularly claimed that the Old Malay of the Srivijayan inscriptions from South Sumatra, Indonesia, is the ancestor of the Classical Malay. However, as noted by some linguists, the precise relationship between these two, whether ancestral or not, is problematic and remains uncertain. This is due to the existence of a number of morphological and syntactic peculiarities, and affixes that are familiar from the related Batak language but are not found even in the oldest manuscripts of Classical Malay. It may be the case that the language of the Srivijayan inscriptions is a close cousin rather than an ancestor of Classical Malay according to Teeuws, hence he asked for more research about it. Moreover, although the earliest evidence of Classical Malay had been found in the Malay Peninsula from 1303, Old Malay remained in use as a written language in Sumatra right up to the end of the 14th century, evidenced from Bukit Gombak inscription dated 1357 and Tanjung Tanah manuscript of Adityavarman era (1347–1375). Later research stated that Old Malay and Modern Malay are forms of the same language in spite of some considerable differences between them.

Classical Malay (14th to 18th century)

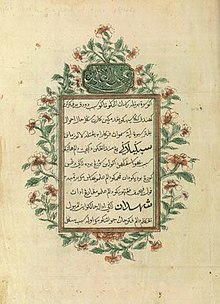

The period of Classical Malay started when Islam gained its foothold in the region and the elevation of its status to a state religion. As a result of Islamisation and growth in trade with the Muslim world, this era witnessed the penetration of Arabic and Persian vocabulary as well as the integration of major Islamic cultures with local Malay culture. The earliest instances of Arabic lexicons incorporated in the pre-Classical Malay written in Kawi was found in the Minye Tujoh inscription dated 1380 CE from Aceh in Sumatra. Nevertheless, pre-Classical Malay took on a more radical form more than half a century earlier as attested in the 1303 CE Terengganu Inscription Stone as well as the 1468 CE Pengkalan Kempas Inscription, both from the Malay Peninsula. Both inscriptions not only serve as the evidence of Islam as a state religion but also as the oldest surviving specimen of the dominant classical orthographic form, the Jawi script. Similar inscriptions containing various adopted Arabic terms with some of them still written the Indianised scripts were also discovered in other parts of Sumatra and Borneo.

The pre-Classical Malay evolved and reached its refined form during the golden age of the Malay empire of Malacca and its successor Johor starting from the 15th century. As a bustling port city with a diverse population of 200,000 from different nations, the largest in Southeast Asia at that time, Malacca became a melting pot of different cultures and languages. More loan words from Arab, Persian, Tamil and Chinese were absorbed and the period witnessed the flowering of Classical Malay literature as well as professional development in royal leadership and public administration. In contrast with Old Malay, the literary themes of Malacca had expanded beyond the decorative belles-lettres and theological works, evidenced with the inclusion of accountancy, maritime laws, credit notes and trade licences in its literary tradition. Some prominent manuscripts of this category are Undang-Undang Melaka (Laws of Malacca) and Undang-Undang Laut Melaka (Maritime Laws of Malacca). The literary tradition was further enriched with the translations of various foreign literary works such as Hikayat Muhammad Hanafiah and Hikayat Amir Hamzah, and the emergence of new intellectual writings in philosophy, tasawuf, tafsir, history and many others in Malay, represented by manuscripts like the Malay Annals and Hikayat Hang Tuah.

Malacca's success as a centre of commerce, religion, and literary output has made it an important point of cultural reference to the many influential Malay sultanates in the later centuries. This has resulted in the growing importance of Classical Malay as the sole lingua franca of the region. Through inter-ethnic contact and trade, the Classical Malay spread beyond the traditional Malay speaking world and resulted in a trade language that was called Melayu Pasar ("Bazaar Malay") or Melayu Rendah ("Low Malay") as opposed to Melayu Tinggi (High Malay) of Malacca-Johor. In fact, Johor even played a key role in the introduction of the Malay language to various areas in the eastern part of the archipelago. It is generally believed that Bazaar Malay was a pidgin, perhaps influenced by contact between Malay, Chinese and non-Malay natives traders. The most important development, however, has been that pidgin Malay creolised, creating several new languages such as the Baba Malay, Betawi Malay and Eastern Indonesian Malay. Apart from being the primary instrument in spreading Islam and commercial activities, Malay also became a court and literary language for kingdoms beyond its traditional realm like Aceh and Ternate and also used in diplomatic communications with the European colonial powers. This is evidenced from diplomatic letters from Sultan Abu Hayat II of Ternate to King John III of Portugal dated from 1521 to 1522, a letter from Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah of Aceh to Captain Sir Henry Middleton of the East India Company dated 1602, and a golden letter from Sultan Iskandar Muda of Aceh to King James I of England dated 1615.

This era also witnessed the growing interest among foreigners in learning the Malay language for the purpose of commerce, diplomatic missions and missionary activities. Therefore, many books in the form of word-list or dictionary were written. The oldest of these was a Chinese-Malay word list compiled by the Ming officials of the Bureau of Translators during the heyday of Malacca Sultanate. The dictionary was known as Man-la-jia Yiyu (滿剌加譯語, Translated Words of Malacca) and contains 482 entries categorised into 17 fields namely astronomy, geography, seasons and times, plants, birds and animals, houses and palaces, human behaviours and bodies, gold and jewelleries, social and history, colours, measurements and general words. In the 16th century, the word-list is believed still in use in China when a royal archive official Yang Lin reviewed the record in 1560 CE. In 1522, the first European-Malay word-list was compiled by an Italian explorer Antonio Pigafetta, who joined the Magellan's circumnavigation expedition. The Italian-Malay word-list by Pigafetta contains approximately 426 entries and became the main reference for the later Latin-Malay and French-Malay dictionaries.

The early phase of European colonisation in Southeast Asia began with the arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century, the Dutch in the 17th century followed by the British in the 18th century. This period also marked the dawn of Christianisation in the region with its stronghold in Malacca, Ambon, Ternate and Batavia. Publication of Bible translations began as early as the seventeenth century although there is evidence that the Jesuit missionary, Francis Xavier, translated religious texts that included Bible verses into Malay as early as the sixteenth century. In fact, Francis Xavier devoted much of his life to missions in just four main centres, Malacca, Amboina and Ternate, Japan and China, two of those were within Malay speaking realm. In facilitating missionary works, religious books and manuscripts began to be translated into Malay of which the earliest was initiated by a pious Dutch trader, Albert Ruyll in 1611. The book titled Sovrat A B C and written in Latin alphabet not only means introducing the Latin alphabet but also the basic tenets of Calvinism that include the Ten Commandments, the faith and some prayers. This work later followed by several Bibles translated into Malay; Injil Mateus dan Markus (1638), Lukas dan Johannes (1646), Injil dan Perbuatan (1651), Kitab Kejadian (1662), Perjanjian Baru (1668) and Mazmur (1689).

Pre-Modern Malay (19th century)

The 19th century was the period of strong Western political and commercial domination in the Malay archipelago. The colonial demarcation brought by the 1824 Anglo-Dutch Treaty led to Dutch East India Company effectively colonising the East Indies in the south while the British Empire held several colonies and protectorates in the Malay peninsula and Borneo in the north. The Dutch and British colonists, realising the importance of understanding the local languages and cultures particularly Malay, began establishing various centres of linguistic, literary and cultural studies in universities like Leiden and London. Thousands of Malay manuscripts, as well as other historical artefacts of Malay culture, were collected and studied. The use of Latin script began to expand in the fields of administration and education whereby the influence of English and Dutch literatures and languages started to penetrate and spread gradually into the Malay language.

At the same time, the technological development in printing method that enabled mass production at low prices increased the activities of authorship for general reading in the Malay language, a development that would later shift away Malay literature from its traditional position in Malay courts. In addition, the report writing style of journalism began to bloom in the arena of Malay writing.

A notable writer of this time was Malacca-born Abdullah Munsyi with his famous works Hikayat Abdullah (1840), Kisah Pelayaran Abdullah ke Kelantan (1838) and Kisah Pelayaran Abdullah ke Mekah (1854). Abdullah's work marks an early stage in the transition from classical to modern literature, taking Malay literature out of its preoccupation with folk-stories and legends into accurate historical descriptions. In fact, Abdullah himself also assisted Claudius Thomsen, a Danish priest, in publishling the first known Malay magazine, the Christian missionary themed Bustan Ariffin in Malacca in 1831, more than a half a century early than the first known Malay newspaper. Abdullah Munsyi is considered the "Father of Modern Malay Literature", being the first local Malay to have his works published.

Many other well-known books were published throughout the archipelago such as three notable classical literary works, Gurindam Dua Belas (1847), Bustanul Katibin (1857) and Kitab Pengetahuan Bahasa (1858) by Selangor-born Raja Ali Haji were also produced in Riau-Lingga during this time. By the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, the Malay literary world was also enlivened by female writers such as Riau-Lingga-born Raja Aisyah Sulaiman, granddaughter of Raja Ali Haji himself with her famous book Hikayat Syamsul Anwar (1890). In this book, she expresses her disapproval regarding her marriage and her attachment to the tradition and the royal court.

The scholars of the Riau-Lingga also established the Rusydiyah Club, one of the first Malay literary organisations, to engage in various literary and intellectual activities in the late 19th century. It was a group of Malay scholars, who discussed various matters related to writing and publishing. There were also other famous religious books of the era that were not only published locally but also in countries like Egypt and Turkey.

Among the earliest examples of Malay newspapers are Soerat Kabar Bahasa Malaijoe of Surabaya published in Dutch East Indies in 1856, Jawi Peranakan of Singapore published in 1876 and Seri Perak of Taiping published in British Malaya in 1893. There was even a Malay newspaper published in Sri Lanka in 1869, known as Alamat Langkapuri, considered the first Malay newspaper ever published in the Jawi script.

In education, the Malay language of Malacca-Johor was regarded as the standard language and became the medium of instruction in schools during the colonial era. Starting in 1821, Malay-medium schools were established by the British colonial government in Penang, Malacca and Singapore. These were followed by many others in the Malay states of the peninsula. This development generated the writing of textbooks for schools, in addition to the publication of reference materials such as Malay dictionaries and grammar books. Apart from that, an important impetus was given toward the use of Malay in British administration, which requires every public servant in service to pass the special examination in the Malay language as a condition for a confirmed post, as published in Straits Government Gazette 1859.

In Indonesia, the Dutch colonial government recognised the Malacca-Johor Malay used in Riau-Lingga as "High Malay" and promoted it as a medium of communication between the Dutch and local population. The language was also taught in schools not only in Riau but also in East Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan and East Indonesia.

Modern Malay (20th century to present)

The flourishing of pre-modern Malay literature in 19th century led to the rise of intellectual movement among the locals and the emergence of new community of Malay linguists. The appreciation of the language grew, and various efforts were undertaken by the community to further enhance the usage of Malay as well as to improve its abilities in facing the challenging modern era. Among the efforts done was the planning of a corpus for the Malay language, first initiated by the Pakatan Belajar-Mengajar Pengetahuan Bahasa (Society for the Learning and Teaching of Linguistic Knowledge), established in 1888. The society that was renamed in 1935 as Pakatan Bahasa Melayu dan Persuratan Buku Diraja Johor (Johor Royal Society of Malay Language and Literary Works), involved actively in arranging and compiling the guidelines for spelling, dictionaries, grammars, punctuations, letters, essays, terminologies and many others. The establishment of the Sultan Idris Training College (SITC) in Tanjung Malim, Perak in 1922 intensified these efforts. In 1936, Za'ba, an outstanding Malay scholar and lecturer of the SITC, produced a Malay grammar book series entitled Pelita Bahasa that modernised the structure of the Classical Malay language and became the basis for the Malay language that is in use today. The most important change was in syntax, from the classical passive form to the modern active form. In the 20th century, other improvements were also carried out by other associations, organisations, governmental institutions and congresses in various part of the region.

Writing has its unique place in the history of self-awareness and the nationalist struggle in Indonesia and Malaysia. Apart from being the main tools to spread knowledge and information, newspapers and journals like Al-Imam (1906), Panji Poestaka (1912), Lembaga Melayu (1914), Warta Malaya (1931), Poedjangga Baroe (1933) and Utusan Melayu (1939) became the main thrust in championing and shaping the fight for nationalism. Writing, whether in the form of novels, short stories, or poems, all played distinct roles in galvanising the spirit of Indonesian National Awakening and Malay nationalism.

During the first Kongres Pemuda of Indonesia held in 1926, Malay was proposed as the unifying language for Indonesia which led to disagreement. This proposal led into the second Kongres Pemuda of Indonesia which held in 1928 and declared "bahasa Indonesia" (Indonesian) as the unifying language for Indonesia in the Sumpah Pemuda. In 1945, the language which was named "bahasa Indonesia", or Indonesian in English, was enshrined as the national language in the constitution of the newly independent Indonesia. Later in 1957, the Malay language was elevated to the status of national language for the independent Federation of Malaya (later reconstituted as Malaysia in 1963). Then in 1959, the Malay language also received the status of national language in Brunei, although it only ceased to become a British protectorate in 1984. When Singapore separated from Malaysia in 1965, Malay became the national language of the new republic and one of the four official languages. The emergence of these newly independent states paved the way for a broader and widespread use of Malay and Indonesian in government administration and education. Colleges and universities with Malay as their primary medium of instructions were introduced and bloomed as the prominent centres for researches and production of new intellectual writings in Malay. Following East Timor independence from Indonesia, the Indonesian language has been designated by the country's 2002 constitution as one of two 'working languages' (the other being English).

— The draft for the third part of Sumpah Pemuda during the first Kongres Pemuda held in 1926. The term Bahasa Melajoe was revised to Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian) in the Sumpah Pemuda 1928."..Kami poetra dan poetri Indonesia mendjoendjoeng bahasa persatoean, bahasa Melajoe,.." (Indonesian for "We, the sons and daughters of Indonesia, vow to uphold the nation's language of unity, the Malay language")

Indonesian as the unifying language for Indonesia is relatively open to accommodating influences from other Indonesian ethnic group languages, Dutch as the previous coloniser, and English as an international language. As a result, Indonesian has wider sources of loanwords, as compared to Malay as used in Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei. It has been suggested that the Indonesian language is an artificial language made official in 1928. By artificial this means that Indonesian was designed by academics rather than evolving naturally as most common languages have, to accommodate the political purpose of establishing an official unifying language of Indonesia. By borrowing heavily from numerous other languages it expresses a natural linguistic evolution; in fact, it is as natural as the next language, as demonstrated in its exceptional capacity for absorbing foreign vocabulary. This disparate evolution of Indonesian language led to a need for an institution that can facilitate co-ordination and co-operation in linguistic development among countries with Malay language as their national language. The first instance of linguistic co-operation was in 1959 between Malaya and Indonesia, and this was further strengthened in 1972 when MBIM (a short form for Majlis Bahasa Indonesia-Malaysia – Language Council of Indonesia-Malaysia) was formed. MBIM later grew into MABBIM (Majlis Bahasa Brunei-Indonesia-Malaysia – Language Council of Brunei-Indonesia-Malaysia) in 1985 with the inclusion of Brunei as a member and Singapore as a permanent observer. Other important institution is Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka established in 1956. It is a government body responsible for co-ordinating the use of the Malay language in Malaysia and Brunei.

The dominant orthographic form of the Modern Malay language based on the Roman or Latin script, the Malay alphabet, was first developed in the early 20th century. As the Malay-speaking countries were divided between two colonial administrations (the Dutch and the British), two major different spelling orthographies were developed in the Dutch East Indies and British Malaya respectively, influenced by the orthographies of their respective colonial tongues. In 1901, the Van Ophuijsen Spelling System (1901–1947) became the standard orthography for the Malay language in the Dutch East Indies. In the following year, the government of the Federated Malay States established an orthographic commission headed by Sir Richard James Wilkinson which later developed the "Wilkinson Spelling System" (1904–1933). These spelling systems would later be succeeded by the Republican Spelling System (1947–1972) and the Za'ba Spelling System (1933–1942) respectively. During the Japanese occupation of Malaya and Indonesia, there emerged a system which was supposed to uniformise the systems in the two countries. The system known as Fajar Asia (or 'the Dawn of Asia') appeared to use the Republican system of writing vowels and the Malayan system of writing consonants. This system only existed during the occupation. In 1972, a declaration was made for a joint spelling system in both nations, known as Ejaan Rumi Baharu (New Rumi Spelling) in Malaysia and Sistem Ejaan Yang Disempurnakan (Perfected Spelling System) in Indonesia. With the introduction of this new common spelling system, all administrative documents, teaching and learning materials and all forms of written communication is based on a relatively uniform spelling system and this helps in effective and efficient communication, particularly in national administration and education.

Despite the widespread and institutionalised use of the Malay alphabet, the Jawi script remains as one of the two official scripts in Brunei, and is used as an alternate script in Malaysia. Day-to-day usage of Jawi is maintained in more conservative Malay-populated areas such as Pattani in Thailand and Kelantan in Malaysia. The script is used for religious and Malay cultural administration in Terengganu, Kelantan, Kedah, Perlis and Johor. The influence of the script is still present in Sulu and Marawi in the Philippines, while in Indonesia the Jawi script is still widely used in Riau and Riau Island province, where road signs and government buildings signs are written in this script.

See also

- Malay literature

- Malay folklore

- Ethnic Malays

- Malayisation

- List of Hikayat

References

- Voorhoeve, P. (1970). "Kerintji Documents". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 126 (4): 369–399. doi:10.1163/22134379-90002797.

- Teeuw 1959, p. 149

- Andaya 2001, p. 317

- Andaya 2001, p. 318

- Molen, Willem van der (2008). "The Syair of Minye Tujuh". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 163 (2/3): 356–375. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003689.

- Sneddon 2003

- Teeuw 1959, pp. 141–143

- Teeuw 1959, p. 148

- Clavé, Elsa; Griffiths, Arlo (11 October 2022). "The Laguna Copperplate Inscription: Tenth-Century Luzon, Java, and the Malay World". Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints. 70 (2): 167–242. doi:10.13185/ps2022.70202. ISSN 2244-1093.

- Adelaar, Alexander (2005). "The Austronesian languages of Asia and Madagascar: A historical perspective". In Adelaar, Alexander; Himmelmann, Nikolaus (eds.). The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 1–42. ISBN 9780415681537.

- Collins 1998, pp. 12–15

- ^ Abdul Rashid & Amat Juhari 2006, p. 29

- Sneddon 2003, pp. 74–77

- Collins 1998, p. 20

- Collins 1998, pp. 15–20

- Sneddon 2003, p. 59

- Sneddon 2003, p. 84

- Sneddon 2003, p. 60

- Collins 1998, pp. 23–27, 44–52

- Braginsky, Vladimir, ed. (2013) . Classical Civilizations of South-East Asia. Routledge. pp. 366–. ISBN 978-1-136-84879-7.

- Edwards, E. D.; Blagden, C. O. (1931). "A Chinese Vocabulary of Malacca Malay Words and Phrases Collected between A. D. 1403 and 1511 (?)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 6 (3): 715–749. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00093204. JSTOR 607205. S2CID 129174700.

- B., C. O. (1939). "Corrigenda and Addenda: A Chinese Vocabulary of Malacca Malay Words and Phrases Collected between A. D. 1403 and 1511 (?)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 10 (1). JSTOR 607921.

- Tan, Chee-Beng (2004). Chinese Overseas: Comparative Cultural Issues. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-962-209-662-2.

- Tan, Chee-Beng (2004). Chinese Overseas: Comparative Cultural Issues. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-962-209-661-5.

- Chew, Phyllis Ghim-Lian (2013). A Sociolinguistic History of Early Identities in Singapore: From Colonialism to Nationalism. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-1-137-01233-3.

- Lach, Donald F. (2010). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume II: A Century of Wonder. Book 3: The Scholarly Disciplines. The University of Chicago Press. pp. 493–. ISBN 978-0-226-46713-9.

- 黃慧敏 (2003). 新馬峇峇文學的研究 (Master's thesis) (in Chinese). 國立政治大學 . p. 21.

- 杨贵谊 (8 May 2003). 四夷馆人编的第一部马来语词典: 《满拉加国译语》. www.nandazhan.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- 安煥然‧明朝人也學馬來話. iconada.tv (in Chinese). 3 August 2014.

- 安煥然‧明朝人也學馬來話. opinions.sinchew.com.my (in Chinese). 3 August 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- 安煥然‧明朝人也學馬來話. iconada.tv (in Chinese). 3 August 2014.

- Braginskiĭ, V. I. (2007). ... and Sails the Boat Downstream: Malay Sufi Poems of the Boat. Department of Languages and Cultures of Southeast Asia and Oceania, University of Leiden. p. 95. ISBN 978-90-73084-24-7.

- Collins 1998, p. 18

- Collins 1998, p. 21

- de Vries, Lourens (2018). "The First Malay Gospel of Mark (1629–1630) and the Agama Kumpeni". Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia. 174 (1). doi:10.1163/22134379-17401002. hdl:1871.1/7ecbd1a4-986b-4448-a78d-3aeb2f13598d. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- Collins 1998, p. 55&61

- ^ Abdul Rashid & Amat Juhari 2006, p. 32

- Sneddon 2003, p. 71

- ^ Abdul Rashid & Amat Juhari 2006, p. 33

- Abdul Rashid & Amat Juhari 2006, p. 35

- Ooi 2008, p. 332

- Abdul Rashid & Amat Juhari 2006, p. 34&35

- Kementerian Sosial RI 2008

- Undang-undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 24 Tahun 2009 Tentang Bendera, Bahasa, dan Lambang Negara, serta Lagu Kebangsaan (Law 24) (in Indonesian). People's Representative Council. 2009.

- Peraturan Gubernur Riau Nomor 46 Tahun 2018 Tentang Penerapan Muatan Budaya Melayu Riau Di Ruang Umum (PDF) (Governor Regulation 46, Article 11) (in Indonesian). Governor of Riau Province. 2018.

Bibliography

- Abdul Rashid, Melebek; Amat Juhari, Moain (2006), Sejarah Bahasa Melayu, Utusan Publications & Distributors, ISBN 967-61-1809-5

- Andaya, Leonard Y. (2001), "The Search for the 'Origins' of Melayu" (PDF), Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 32 (3): 315–330, doi:10.1017/s0022463401000169, S2CID 62886471

- Arkib Negara Malaysia (2012), Persada Kegemilangan Bahasa Melayu, archived from the original on 29 August 2012, retrieved 27 September 2012

- Asmah, Haji Omar (2004), The Encyclopedia of Malaysia: Languages & Literature, Editions Didlers Millet, ISBN 981-3018-52-6

- Collins, James T (1998), Malay, World Language: A Short History, Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, ISBN 978-979-461-537-9

- Kementerian Sosial RI (2008), Sumpah itu, 80 tahun kemudian, archived from the original on 29 September 2013, retrieved 19 October 2012

- Mohamed Pitchay Gani, Mohamed Abdul Aziz (2004), E-Kultur dan evolusi bahasa Melayu di Singapura (Master Thesis), National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University

- Morrison, George Ernest (1975), "The Early Cham Language and Its Relation to Malay", Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 48

- Noriah, Mohamed (1999), Sejarah Sosiolinguistik Bahasa Melayu Lama, Penerbit Universiti Sains Malaysia, ISBN 983-861-184-0

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2008), Historical Dictionary of Malaysia, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0-8108-5955-5

- Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu (2012), Sejarah Perkembangan Bahasa Melayu, retrieved 27 September 2012

- Sneddon, James N. (2003), The Indonesian Language: Its History and Role in Modern Society, University of New South Wales Press, ISBN 0-86840-598-1

- Teeuw, Andries (1959), The History of the Malay Language: A Preliminary Survey, Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, retrieved 17 October 2012

- Thurgood, Graham (1999), From Ancient Cham to Modern Dialects: Two Thousand Years of Language Contact and Change, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2131-9

External links

- Old Malay inscriptions

- Loan-Words in Indonesian and Malay - compiled by the Indonesian etymological project (Russell Jones, general editor)

| Histories of the world's languages | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indo-European |

| ||||||||||||||

| Uralic | |||||||||||||||

| Other European | |||||||||||||||

| Afroasiatic | |||||||||||||||

| Dravidian | |||||||||||||||

| Austroasiatic | |||||||||||||||

| Austronesian | |||||||||||||||

| Sino–Tibetan | |||||||||||||||

| Japonic | |||||||||||||||

| Koreanic | |||||||||||||||

| Iroquoian | |||||||||||||||

| Turkic | |||||||||||||||

| constructed | |||||||||||||||