| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Pap test" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Papanicolaou test | |

|---|---|

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion | |

| Specialty | Gynaecology |

| ICD-9-CM | 795.00 |

| MeSH | D014626 |

| MedlinePlus | 003911 |

| [edit on Wikidata] | |

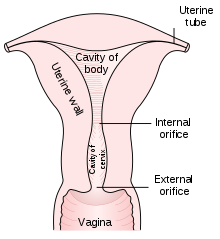

The Papanicolaou test (abbreviated as Pap test, also known as Pap smear (AE), cervical smear (BE), cervical screening (BE), or smear test (BE)) is a method of cervical screening used to detect potentially precancerous and cancerous processes in the cervix (opening of the uterus or womb) or, more rarely, anus (in both men and women). Abnormal findings are often followed up by more sensitive diagnostic procedures and, if warranted, interventions that aim to prevent progression to cervical cancer. The test was independently invented in the 1920s by the Greek physician Georgios Papanikolaou and named after him. A simplified version of the test was introduced by the Canadian obstetrician Anna Marion Hilliard in 1957.

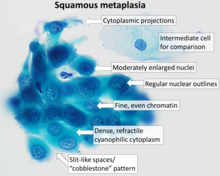

A Pap smear is performed by opening the vagina with a speculum and collecting cells at the outer opening of the cervix at the transformation zone (where the outer squamous cervical cells meet the inner glandular endocervical cells), using an Ayre spatula or a cytobrush. The collected cells are examined under a microscope to look for abnormalities. The test aims to detect potentially precancerous changes (called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or cervical dysplasia; the squamous intraepithelial lesion system (SIL) is also used to describe abnormalities) caused by human papillomavirus, a sexually transmitted DNA virus. The test remains an effective, widely used method for early detection of precancer and cervical cancer. While the test may also detect infections and abnormalities in the endocervix and endometrium, it is not designed to do so.

Guidelines on when to begin Pap smear screening are varied, but usually begin in adulthood. Guidelines on frequency vary from every three to five years. If results are abnormal, and depending on the nature of the abnormality, the test may need to be repeated in six to twelve months. If the abnormality requires closer scrutiny, the patient may be referred for detailed inspection of the cervix by colposcopy, which magnifies the view of the cervix, vagina and vulva surfaces. The person may also be referred for HPV DNA testing, which can serve as an adjunct to Pap testing. In some countries, viral DNA is checked for first, before checking for abnormal cells. Additional biomarkers that may be applied as ancillary tests with the Pap test are evolving.

Medical uses

| Summary of reasons for testing | ||

|---|---|---|

| patient's characteristic | indication | rationale |

| under age 21, regardless of sexual history | no test | more harms than benefits |

| age 20–25 until age 50–60 | test every 3–5 years if results normal | broad recommendation |

| over age 65; history of normal tests | no further testing | recommendation of USPSTF, ACOG, ACS and ASCP; |

| had total hysterectomy for non-cancer disease – cervix removed | no further testing | harms of screening after hysterectomy outweigh the benefits |

| had partial hysterectomy – cervix remains | continue testing as normal | |

| has received HPV vaccine | continue testing as normal | vaccine does not cover all cancer-causing types of HPV |

| history of endometrial cancer, with history of hysterectomy | discontinue routine testing | test no longer effective and likely to give false positive |

Screening guidelines vary from country to country. In general, screening starts about the age of 20 or 25 and continues until about the age of 50 or 60. Screening is typically recommended every three to five years, as long as results are normal.

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and others recommend starting screening at age 21. Many other countries wait until age 25 or later to start screening. For instance, some parts of Great Britain start screening at age 25. ACOG's general recommendation is that people with female reproductive organs age 30–65 have an annual well-woman examination, that they not get annual Pap tests, and that they do get Pap tests at three to five year intervals.

HPV is passed through skin to skin contact; sex does not have to occur, although it is a common way for it to spread. It takes an average of a year, but can take up to four years, for a person's immune system to clear the initial infection. Screening during this period may show this immune reaction and repair as mild abnormalities, which are usually not associated with cervical cancer, but could cause the patient stress and result in further tests and possible treatment. Cervical cancer usually takes time to develop, so delaying the start of screening a few years poses little risk of missing a potentially precancerous lesion. For instance, screening people under age 25 does not decrease cancer rates under age 30.

HPV can be transmitted in sex between females, so those who have only had sex with other females should be screened, although they are at somewhat lower risk for cervical cancer.

Guidelines on frequency of screening vary—typically every three to five years for those who have not had previous abnormal smears. Some older recommendations suggested screening as frequently as every one to two years, however there is little evidence to support such frequent screening; annual screening has little benefit but leads to greatly increased cost and many unnecessary procedures and treatments. It has been acknowledged since before 1980 that most people can be screened less often. In some guidelines, frequency depends on age; for instance in Great Britain, screening is recommended every three years for women under 50, and every five years for those over.

Screening should stop at about age 65 unless there is a history of abnormal test result or disease. There is probably no benefit in screening people aged 60 or over whose previous tests have been negative. If a woman's last three Pap results were normal, she can discontinue testing at age 65, according to the USPSTF, ACOG, ACS, and ASCP; England's NHS says 64. There is no need to continue screening after a complete hysterectomy for benign disease.

Pap smear screening is still recommended for those who have been vaccinated against HPV since the vaccines do not cover all HPV types that can cause cervical cancer. Also, the vaccine does not protect against HPV exposure before vaccination.

Those with a history of endometrial cancer should discontinue routine Pap tests after hysterectomy. Further tests are unlikely to detect recurrence of cancer but do bring the risk of giving false positive results, which would lead to unnecessary further testing.

More frequent Pap smears may be needed to follow up after an abnormal Pap smear, after treatment for abnormal Pap or biopsy results, or after treatment of cancer (cervical, anal, etc.).

Effectiveness

The Pap test, when combined with a regular program of screening and appropriate follow-up, can reduce cervical cancer deaths by up to 80%.

Failure of prevention of cancer by the Pap test can occur for many reasons, including not getting regular screening, lack of appropriate follow-up of abnormal results, and sampling and interpretation errors. In the US, over half of all invasive cancers occur in females who have never had a Pap smear; an additional 10 to 20% of cancers occur in those who have not had a Pap smear in the preceding five years. About one-quarter of US cervical cancers were in people who had an abnormal Pap smear but did not get appropriate follow-up (patient did not return for care, or clinician did not perform recommended tests or treatment).

Adenocarcinoma of the cervix has not been shown to be prevented by Pap smears. In the UK, which has a Pap smear screening program, adenocarcinoma accounts for about 15% of all cervical cancers.

Estimates of the effectiveness of the United Kingdom's call and recall system vary widely, but it may prevent about 700 deaths per year in the UK.

Multiple studies have performed sensitivity and specificity analyses on Pap smears. Sensitivity analysis captures the ability of Pap smears to correctly identify women with cervical cancer. Various studies have revealed the sensitivity of Pap smears to be between 47.19 - 55.5%. Specificity analysis captures the ability of Pap smears to correctly identify women without cervical cancer. Various studies have revealed the specificity of Pap smears to be between 64.79 - 96.8%. While Pap smears may not be entirely accurate, they remain one of the most effective cervical cancer prevention tools. Pap smears may be supplemented with HPV DNA testing.

Results

In screening a general or low-risk population, most Pap results are normal.

In the United States, about 2–3 million abnormal Pap smear results are found each year. Most abnormal results are mildly abnormal (ASC-US (typically 2–5% of Pap results) or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) (about 2% of results)), indicating HPV infection. Although most low-grade cervical dysplasias spontaneously regress without ever leading to cervical cancer, dysplasia can serve as an indication that increased vigilance is needed.

In a typical scenario, about 0.5% of Pap results are high-grade SIL (HSIL), and less than 0.5% of results indicate cancer; 0.2 to 0.8% of results indicate Atypical Glandular Cells of Undetermined Significance (AGC-NOS).

As liquid-based preparations (LBPs) become a common medium for testing, atypical result rates have increased. The median rate for all preparations with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions using LBPs was 2.9% in 2006, compared with a 2003 median rate of 2.1%. Rates for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (median, 0.5%) and atypical squamous cells have changed little.

Abnormal results are reported according to the Bethesda system. They include:

- Atypical squamous cells (ASC)

- Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US)

- Atypical squamous cells – cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H)

- Squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL)

- Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LGSIL or LSIL)

- High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL or HSIL)

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Glandular epithelial cell abnormalities

- Atypical glandular cells not otherwise specified (AGC or AGC-NOS)

Endocervical and endometrial abnormalities can also be detected, as can a number of infectious processes, including yeast, herpes simplex virus and trichomoniasis. However it is not very sensitive at detecting these infections, so absence of detection on a Pap does not mean absence of the infection.

-

Micrograph of a normal pap smear

Micrograph of a normal pap smear

-

Micrograph of a Pap test showing a low-grade intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) and benign endocervical mucosa. Pap stain.

Micrograph of a Pap test showing a low-grade intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) and benign endocervical mucosa. Pap stain.

-

Micrograph of a Pap test showing trichomoniasis. Trichomonas organism seen in the upper right. Pap stain.

Micrograph of a Pap test showing trichomoniasis. Trichomonas organism seen in the upper right. Pap stain.

-

Micrograph of a Pap test showing changes of herpes simplex virus. Pap stain.

Micrograph of a Pap test showing changes of herpes simplex virus. Pap stain.

-

Endocervical adenocarcinoma on a pap test.

Endocervical adenocarcinoma on a pap test.

-

Candida organisms on a pap test.

Candida organisms on a pap test.

-

Viral cytopathic effect consistent with herpes simplex virus on a pap test.

Viral cytopathic effect consistent with herpes simplex virus on a pap test.

-

Normal squamous epithelial cells in premenopausal women

Normal squamous epithelial cells in premenopausal women

-

Atrophic squamous cells in postmenopausal women

-

Normal endocervical cells should be present into the slide, as a proof of a good quality sampling

-

The cytoplasms of squamous epithelial cells melted out; many Döderlein bacilli can be seen.

-

Infestation by Trichomonas vaginalis

-

An obviously atypical cell can be seen

Pregnancy

Pap tests can usually be performed during pregnancy up to at least 24 weeks of gestational age. Pap tests during pregnancy have not been associated with increased risk of miscarriage. An inflammatory component is commonly seen on Pap smears from pregnant women and does not appear to be a risk for subsequent preterm birth.

After childbirth, it is recommended to wait 12 weeks before taking a Pap test because inflammation of the cervix caused by the birth interferes with test interpretation.

In transgender individuals

Transgender men are also typically at risk for HPV due to retention of the uterine cervix in the majority of individuals in this subgroup. As such, professional guidelines recommend that transgender men be screened routinely for cervical cancer using methods such as Pap smear, identical to the recommendations for cisgender women.

However, transgender men have lower rates of cervical cancer screening than cisgender women. Many transgender men report barriers to receiving gender-affirming healthcare, including lack of insurance coverage and stigma/discrimination during clinical encounters, and may encounter provider misconceptions regarding risk in this population for cervical cancer. Pap smears may be presented to patients as non-gendered screening procedures for cancer rather than one specific for examination of the female reproductive organs. Pap smears may trigger gender dysphoria in patients and gender-neutral language can be used when explaining the pathogenesis of cancer due to infection, emphasizing the pervasiveness of HPV infection regardless of gender.

Transgender women who have not had vaginoplasties are not at risk of developing cervical cancer because they do not have cervices. Transgender women who have had vaginoplasties and have a neo-cervix or neo-vagina have a small chance of developing cancer, according to the Canadian Cancer Society. Surgeons typically use penile skin to create the new vagina and cervix, which can contract HPV and lead to penile cancer, although it is considerably rarer than cervical cancer. Because the risk of this kind of cancer is so low, cervical cancer screening is not routinely offered for those with a neo-cervix.

Procedure

According to the CDC, intercourse, douching, and the use of vaginal medicines or spermicidal foam should be avoided for 2 days before the test. A number of studies have shown that using a small amount of water-based gel lubricant does not interfere with, obscure, or distort the Pap smear. Further, cytology is not affected, nor are some STD testing. The CDC states that Pap smears can be performed during menstruation. However, the NHS recommends against cervical screening during, or in the 2 days before and after, menstruation. Pap smears can be performed during menstruation, especially if the physician is using a liquid-based test; however if bleeding is extremely heavy, endometrial cells can obscure cervical cells, and if this occurs the test may need to be repeated in 6 months.

Pap smears begin with the insertion of a speculum into the vagina, which spreads the vagina open and allows access to the cervix. The health care provider then collects a sample of cells from the outer opening or external os of the cervix by scraping it with either a spatula or brush.

Obtaining a Pap smear should not cause much pain, but may be uncomfortable. Conditions such as vaginismus, vulvodynia, or cervical stenosis can cause insertion of the speculum to be painful.

In a conventional Pap smear, the cells are placed on a glass slide and taken to the laboratory to be checked for abnormalities.

A plastic-fronded broom is sometimes used in place of the spatula or brush. The broom is not as good a collection device, since it is much less effective at collecting endocervical material than the spatula and brush. The broom is used more frequently with the advent of liquid-based cytology, although either type of collection device may be used with either type of cytology.

The sample is stained using the Papanicolaou technique, in which tinctorial dyes and acids are selectively retained by cells. Unstained cells cannot be seen adequately with a light microscope. Papanicolaou chose stains that highlighted cytoplasmic keratinization, which actually has almost nothing to do with the nuclear features used to make diagnoses now.

A single smear has an area of 25 x 50 mm and contains a few hundred thousand cells on average. Screening with light microscopy is first done on low (10x) power and then switched to higher (40x) power upon viewing suspicious findings. Cells are analyzed under high power for morphologic changes indicative of malignancy (including enlarged and irregularly shaped nucleus, an increase in nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, and more coarse and irregular chromatin). Approximately 1,000 fields of view are required on 10x power for screening of a single sample, which takes on average 5 to 10 minutes.

In some cases, a computer system may prescreen the slides, indicating those that do not need examination by a person or highlighting areas for special attention. The sample is then usually screened by a specially trained and qualified cytotechnologist using a light microscope. The terminology for who screens the sample varies according to the country; in the UK, the personnel are known as cytoscreeners, biomedical scientists (BMS), advanced practitioners and pathologists. The latter two take responsibility for reporting the abnormal sample, which may require further investigation.

Automated analysis

In the last decade, there have been successful attempts to develop automated, computer image analysis systems for screening. Although, on the available evidence automated cervical screening could not be recommended for implementation into a national screening program, a recent NHS Health technology appraisal concluded that the 'general case for automated image analysis ha(d) probably been made'. Automation may improve sensitivity and reduce unsatisfactory specimens. Two systems have been approved by the FDA and function in high-volume reference laboratories, with human oversight.

Types of screening

For other cervical screening tests and human papillomavirus testing, see Cervical screening.- Conventional Pap—In a conventional Pap smear, samples are smeared directly onto a microscope slide after collection.

- Liquid-based cytology—The sample of (epithelial) cells is taken from the transitional zone, the squamocolumnar junction of the cervix, between the ectocervix and the endocervix. The cells taken are suspended in a bottle of preservative for transport to the laboratory, where they are analyzed using Pap stains.

Type 1: Completely ectocervical.

Type 2: Endocervical component but fully visible.

Type 3: Endocervical component, not fully visible.

Pap tests commonly examine epithelial abnormalities, such as metaplasia, dysplasia, or borderline changes, all of which may be indicative of CIN. Nuclei will stain dark blue, squamous cells will stain green and keratinised cells will stain pink/ orange. Koilocytes may be observed where there is some dyskaryosis (of epithelium). The nucleus in koilocytes is typically irregular, indicating possible cause for concern; requiring further confirmatory screens and tests.

In addition, human papillomavirus (HPV) test may be performed either as indicated for abnormal Pap results, or in some cases, dual testing is done, where both a Pap smear and an HPV test are done at the same time (also called Pap co-testing).

Practical aspects

The endocervix may be partially sampled with the device used to obtain the ectocervical sample, but due to the anatomy of this area, consistent and reliable sampling cannot be guaranteed. Since abnormal endocervical cells may be sampled, those examining them are taught to recognize them.

The endometrium is not directly sampled with the device used to sample the ectocervix. Cells may exfoliate onto the cervix and be collected from there, so as with endocervical cells, abnormal cells can be recognised if present but the Pap test should not be used as a screening tool for endometrial malignancy.

In the United States, a Pap test itself costs $20 to $30, but the costs for Pap test visits can cost over $1,000, largely because additional tests are added that may or may not be necessary.

History

The test was invented by and named after the Greek doctor Georgios Papanikolaou, who started his research in 1923. Aurel Babeș independently made similar discoveries in 1927. However, Babeș' method was radically different from Papanikolaou's.

The Pap test was finally recognized only after a leading article in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology in 1941 by Papanikolaou and Herbert F. Traut, an American gynecologist. A monograph titled Diagnosis of Uterine Cancer by the Vaginal Smear that they published contained drawings of the various cells seen in patients with no disease, inflammatory conditions, and preclinical and clinical carcinoma. The monograph was illustrated by Hashime Murayama, who later became a staff illustrator with the National Geographic Society. Both Papanikolaou and his wife, Andromachi Papanikolaou, dedicated the rest of their lives to teaching the technique to other physicians and laboratory personnel.

Experimental techniques

In the developed world, cervical biopsy guided by colposcopy is considered the "gold standard" for diagnosing cervical abnormalities after an abnormal Pap smear. Other techniques such as triple smear are also done after an abnormal Pap smear. The procedure requires a trained colposcopist and can be expensive to perform. However, Pap smears are very sensitive and some negative biopsy results may represent undersampling of the lesion in the biopsy, so negative biopsy with positive cytology requires careful follow-up.

Experimental visualization techniques use broad-band light (e.g., direct visualization, speculoscopy, cervicography, visual inspection with acetic acid or with Lugol's, and colposcopy) and electronic detection methods (e.g., Polarprobe and in vivo spectroscopy). These techniques are less expensive and can be performed with significantly less training. They do not perform as well as Pap smear screening and colposcopy. At this point, these techniques have not been validated by large-scale trials and are not in general use.

Implementation by country

Australia

Australia has used the Pap test as part of its cervical screening program since its implementation in 1991 which required women past the age of 18 be tested every two years. In December 2017 Australia discontinued its use of the Pap test and replaced it with a new HPV test that is only required to be conducted once every five years from the age of 25. Medicare covers the costs of testing; however, if a patient's doctor does not allow bulk billing, they may have to pay for the appointment and then claim the Medicare rebate.

Taiwan

Free Pap tests were offered from 1974–1984 before being replaced by a system in which all women over the age of 30 could have the cost of their Pap test reimbursed by the National Health Insurance in 1995. This policy was still ongoing in 2018 and encouraged women to screen at least every three years.

Despite this, the number of people receiving Pap tests remain lower than countries like Australia. Some believe this is due to a lack of awareness regarding the test and its availability. It has also been found that women who have chronic diseases or other reproductive diseases are less likely to receive the test.

England

As of 2020 the NHS maintains a cervical screening program in which women between the age of 25–49 are invited for a smear test every three years, and women past 50 every five years. Much like Australia, England uses a HPV test before examining cells that test positive using the Pap test. The test is free as part of the national cervical screening program.

Coccoid bacteria

The finding of coccoid bacteria on a Pap test is of no consequence with otherwise normal test findings and no infectious symptoms. However, if there is enough inflammation to obscure the detection of precancerous and cancerous processes, it may indicate treatment with a broad-spectrum antibiotic for streptococci and anaerobic bacteria (such as metronidazole and amoxicillin) before repeating the smear. Alternatively, the test will be repeated at an earlier time than it would otherwise. If there are symptoms of vaginal discharge, bad odor or irritation, the presence of coccoid bacteria also may indicate treatment with antibiotics as per above.

References

- Notes

- "Pap Smear: MedlinePlus Lab Test Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- "Cervical Screening". NHS. 2017-10-20. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- Lindsey, Kimberley; DeCristofaro, Claire; James, Janet (August 2009). "Anal Pap smears: Should we be doing them?". Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 21 (8): 437–443. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00433.x. PMID 19689440.

- Moyer, VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force (Jun 19, 2012). "Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 156 (12): 880–91, W312. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00424. PMID 22711081. S2CID 36965456.

- ^ Saslow, Debbie; Solomon, Diane; Lawson, Herschel W.; Killackey, Maureen; Kulasingam, Shalini L.; Cain, Joanna M.; Garcia, Francisco A. R.; Moriarty, Ann T.; Waxman, Alan G.; Wilbur, David C.; Wentzensen, Nicolas; Downs, Levi S.; Spitzer, Mark; Moscicki, Anna-Barbara; Franco, Eduardo L.; Stoler, Mark H.; Schiffman, Mark; Castle, Philip E.; Myers, Evan R. (July 2012). "American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology Screening Guidelines for the Prevention and Early Detection of Cervical Cancer". Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 16 (3): 175–204. doi:10.1097/LGT.0b013e31824ca9d5. PMC 3915715. PMID 22418039.

- American Cancer Society. (2010). Detailed Guide: Cervical Cancer. Can cervical cancer be prevented? Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2009). "ACOG Education Pamphlet AP085 – The Pap Test". Washington, DC. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- "Cervical cancer screening in England to use 'more accurate' viral DNA test". Cancer Research UK - Cancer News. 2016-07-05. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- Shidham, VinodB; Mehrotra, Ravi; Varsegi, George; D′Amore, Krista L; Hunt, Bryan; Narayan, Raj (2011-01-01). "p16 INK4a immunocytochemistry on cell blocks as an adjunct to cervical cytology: Potential reflex testing on specially prepared cell blocks from residual liquid-based cytology specimens". CytoJournal. 8 (1): 1. doi:10.4103/1742-6413.76379. PMC 45765. PMID 21369522.

- ^ American Academy of Family Physicians. "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF). Choosing Wisely: An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, Ronco G, Schenck U, Segnan N, Wiener H, Herbert A, von Karsa L (2010). "European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening. Second Edition—Summary Document". Annals of Oncology. 21 (3): 448–458. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp471. PMC 2826099. PMID 20176693.

- ^ Strander, B (2009). "At what age should cervical screening stop?". Br Med J. 338: 1022–23. doi:10.1136/bmj.b809. PMID 19395422. S2CID 37206485.

- ^ Sasieni P, Adams J, Cuzick J (2003). "Benefit of cervical screening at different ages: evidence from the UK audit of screening histories". Br J Cancer. 89 (1): 88–93. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600974. PMC 2394236. PMID 12838306.

- ^ Society of Gynecologic Oncology (February 2014). "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely: An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Retrieved 19 February 2013., which cites

- Salani R, Backes FJ, Fung MF, Holschneider CH, Parker LP, Bristow RE, Goff BA (2011). "Posttreatment surveillance and diagnosis of recurrence in women with gynecologic malignancies: Society of Gynecologic Oncologists recommendations". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 204 (6): 466–78. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.008. PMID 21752752.

- Salani R, Nagel CI, Drennen E, Bristow RE (2011). "Recurrence patterns and surveillance for patients with early stage endometrial cancer". Gynecologic Oncology. 123 (2): 205–7. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.07.014. PMID 21820709.

- Bristow RE, Purinton SC, Santillan A, Diaz-Montes TP, Gardner GJ, Giuntoli RL (2006). "Cost-effectiveness of routine vaginal cytology for endometrial cancer surveillance". Gynecologic Oncology. 103 (2): 709–13. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.013. PMID 16797686.

- ACOG Committee on Gynecological Practice (2009). "ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice; Routine Pelvic Examination and Cervical Cytology Screening, Opinion #413". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 113 (5): 1190–1193. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a6d022. PMID 19384150.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely: An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Retrieved August 1, 2013., which cites

- Boulware LE, Marinopoulos S, Phillips KA, Hwang CW, Maynor K, Merenstein D, Wilson RF, Barnes GJ, Bass EB, Powe NR, Daumit GL (2007). "Systematic review: The value of the periodic health evaluation". Annals of Internal Medicine. 146 (4): 289–300. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-4-200702200-00008. PMID 17310053. S2CID 1683342.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain J, Garcia FA, Moriarty AT, Waxman AG, Wilbur DC, Wentzensen N, Downs LS, Spitzer M, Moscicki AB, Franco EL, Stoler MH, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Myers ER (2012). "American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer". CA Cancer J Clin. 62 (3): 147–72. doi:10.3322/caac.21139. PMC 3801360. PMID 22422631.

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice (2012). "Committee Opinion No. 534". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 120 (2, Part 1): 421–424. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182680517. PMID 22825111.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology (2012). "ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 131: Screening for cervical cancer". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 120 (5): 1222–1238. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318277c92a. PMID 23090560.

- "Can Cervical Cancer Be Prevented?". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Sasieni, P; Castanon, A; Cuzick, J; Snow, J (2009). "Effectiveness of Cervical Screening with Age: Population based Case-Control Study of Prospectively Recorded Data". BMJ. 339: 2968–2974. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2968. PMC 2718082. PMID 19638651.

- Marrazzo JM, Koutsky LA, Kiviat NB, Kuypers JM, Stine K (2001). "Papanicolaou test screening and prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among women who have sex with women". American Journal of Public Health. 91 (6): 947–952. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.6.947. PMC 1446473. PMID 11392939.

- Smith, RA; et al. (2002). "American Cancer Society Guideline for the Early Detection of Cervical Neoplasia and Cancer". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 52 (1): 8–22. doi:10.3322/canjclin.52.6.342. PMID 12469763. S2CID 19919545.

ACS and others have recommended, since before 1980, that conventional cytology can be safely performed up to every three years for most women.

- "Cervical screening: programme overview". Gov.UK. Public Health England. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- "HPV Vaccination Recommendations". Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. 22 May 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- Salani, R (2017). "An update on post-treatment surveillance and diagnosis of recurrence in women with gynecologic malignancies: Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) recommendations" (PDF). Gynecologic Oncology. 146 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.022. PMID 28372871. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-07-02.

- "HPV and Pap Test Results: Next Steps after an Abnormal Test - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 2022-10-13. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ^ DeMay, M. (2007). Practical principles of cytopathology. Revised edition. Chicago, IL: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press. ISBN 978-0-89189-549-7.

- "Cancer Research UK website". Archived from the original on 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- Raffle AE, Alden B, Quinn M, Babb PJ, Brett MT (2003). "Outcomes of screening to prevent cancer: analysis of cumulative incidence of cervical abnormality and modelling of cases and deaths prevented". BMJ. 326 (7395): 901. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7395.901. PMC 153831. PMID 12714468.

- ^ "Specificity, sensitivity and cost". Nature Reviews Cancer. 7 (12): 893. December 2007. doi:10.1038/nrc2287. ISSN 1474-1768. S2CID 43571578.

- ^ Najib, Fatemeh sadat; Hashemi, Masooumeh; Shiravani, Zahra; Poordast, Tahereh; Sharifi, Sanam; Askary, Elham (September 2020). "Diagnostic Accuracy of Cervical Pap Smear and Colposcopy in Detecting Premalignant and Malignant Lesions of Cervix". Indian Journal of Surgical Oncology. 11 (3): 453–458. doi:10.1007/s13193-020-01118-2. ISSN 0975-7651. PMC 7501362. PMID 33013127.

- ^ Nkwabong, Elie; Laure Bessi Badjan, Ingrid; Sando, Zacharie (January 2019). "Pap smear accuracy for the diagnosis of cervical precancerous lesions". Tropical Doctor. 49 (1): 34–39. doi:10.1177/0049475518798532. ISSN 0049-4755. PMID 30222058. S2CID 52280945.

- ^ "Pap Smear". Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- Eversole GM, Moriarty AT, Schwartz MR, Clayton AC, Souers R, Fatheree LA, Chmara BA, Tench WD, Henry MR, Wilbur DC (2010). "Practices of participants in the college of american pathologists interlaboratory comparison program in cervicovaginal cytology, 2006". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 134 (3): 331–5. doi:10.5858/134.3.331. PMID 20196659.

- Nayar, Ritu; Solomon, Diane (2004-01-01). "Second edition of 'The Bethesda System for reporting cervical cytology' - Atlas, website, and Bethesda interobserver reproducibility project". CytoJournal. 1 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/1742-6413-1-4. PMC 526759. PMID 15504231.

- ^ PapScreen Victoria > Pregnant women Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine from Cancer Council Victoria 2014

- Michael CW (1999). "The Papanicolaou Smear and the Obstetric Patient: A Simple Test with Great Benefits". Diagnostic Cytopathology. 21 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(199907)21:1<1::AID-DC1>3.0.CO;2-0. hdl:2027.42/35304. PMID 10405797. S2CID 1367319.

- Lanouette JM, Puder KS, Berry SM, Bryant DR, Dombrowski MP (1997). "Is inflammation on Papanicolaou smear a risk factor for preterm delivery?". Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 12 (4): 244–247. doi:10.1159/000264477. PMID 9354886.

- "Pregnant women". papscreen.org. Cancer Council Victoria. Archived from the original on 2015-01-08. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- Grant, Jaime M. (2010). National Transgender Discrimination Survey report on health and health care : findings of a study by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. National Center for Transgender Equality. OCLC 707939280.

- ^ "Should trans men have cervical screening tests?". NHS. 2018-06-27. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- "Committee Opinion No. 512: Health Care for Transgender Individuals". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 118 (6): 1454–1458. December 2011. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823ed1c1. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 22105293.

- Peitzmeier, Sarah M.; Khullar, Karishma; Reisner, Sari L.; Potter, Jennifer (December 2014). "Pap Test Use Is Lower Among Female-to-Male Patients Than Non-Transgender Women". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 47 (6): 808–812. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.031. PMID 25455121.

- Grant, Jaime M. (2011). Injustice at every turn : a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. OCLC 777348181.

- Snelgrove, John W; Jasudavisius, Amanda M; Rowe, Bradley W; Head, Evan M; Bauer, Greta R (December 2012). ""Completely out-at-sea" with "two-gender medicine": A qualitative analysis of physician-side barriers to providing healthcare for transgender patients". BMC Health Services Research. 12 (1): 110. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-110. ISSN 1472-6963. PMC 3464167. PMID 22559234.

- Poteat, Tonia; German, Danielle; Kerrigan, Deanna (May 2013). "Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters". Social Science & Medicine. 84: 22–29. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019. PMID 23517700. S2CID 5339596.

- Reisner, Sari L.; Gamarel, Kristi E.; Dunham, Emilia; Hopwood, Ruben; Hwahng, Sel (September 2013). "Female-to-Male Transmasculine Adult Health: A Mixed-Methods Community-Based Needs Assessment". Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 19 (5): 293–303. doi:10.1177/1078390313500693. ISSN 1078-3903. PMID 23963876. S2CID 3285779.

- Potter, Jennifer; Peitzmeier, Sarah M.; Bernstein, Ida; Reisner, Sari L.; Alizaga, Natalie M.; Agénor, Madina; Pardee, Dana J. (2015-07-10). "Cervical Cancer Screening for Patients on the Female-to-Male Spectrum: a Narrative Review and Guide for Clinicians". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 30 (12): 1857–1864. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3462-8. ISSN 0884-8734. PMC 4636588. PMID 26160483.

- "As a trans woman, do I need to get screened for cervical cancer". Canadian Cancer Society.

- ^ "I'm trans or non-binary, does this affect my cancer screening?". Cancer Research UK. 2019-10-10. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- Anonymous (2020-09-04). "Cervical screening for trans men and/or non-binary people". Jo's Cervical Cancer Trust. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- "Tweet misleads on cervical cancer guidance for trans women". AP News. 2023-03-17. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ "Screening for Cervical Cancer". CDC. 26 October 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- Wright, Jessica L. (2010). "The Effect of Using Water-based Gel Lubricant During a Speculum Exam On Pap Smear Results". School of Physician Assistant Studies. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- "How to book cervical screening". NHS. 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- Chan, Paul D. (2006). Gynecology and obstetrics : new treatment guidelines. Internet Archive. Laguna Hills, CA : Current Clinical Strategies Pub. ISBN 978-1-929622-63-4.

- "Cervical Cancer Screening - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 2022-10-13. Retrieved 2023-08-09.

- "Excerpts from Changing Bodies, Changing Lives". Our Bodies Ourselves. Archived from the original on 2013-12-18. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- "Cervical screening: support for people who feel anxious about attending". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2023-08-09.

- "All About Speculums: Finding What Works for You". www.ohsu.edu. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- Biggs, Kirsty V.; Soo Hoo, San; Kodampur, Mallikarjun (April 2022). "Mechanical dilatation of the stenosed cervix under local anesthesia: A prospective case series". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 48 (4): 956–965. doi:10.1111/jog.15179. ISSN 1341-8076. PMC 9303640. PMID 35132727.

- "Conventional Pap Test". Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene. Retrieved 2023-08-09.

- Martin-Hirsch P, Lilford R, Jarvis G, Kitchener HC (1999). "Efficacy of cervical-smear collection devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 354 (9192): 1763–1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02353-3. PMID 10577637. S2CID 22733963.

- Bengtsson, Ewert; Malm, Patrik (2014). "Screening for Cervical Cancer Using Automated Analysis of PAP-Smears". Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine. 2014: 842037. doi:10.1155/2014/842037. ISSN 1748-670X. PMC 3977449. PMID 24772188.

- Biscotti CV, Dawson AE, Dziura B, Galup L, Darragh T, Rahemtulla A, Wills-Frank L (2005). "Assisted primary screening using the automated ThinPrep Imaging System". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 123 (2): 281–7. doi:10.1309/AGB1MJ9H5N43MEGX. PMID 15842055.

- Willis BH, Barton P, Pearmain P, Bryan S, Hyde C, "Cervical screening programmes: can automation help? Evidence from systematic reviews, an economic analysis and a simulation modelling exercise applied to the UK". Health Technol Assess 2005 9(13). Archived 2008-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Davey E, d'Assuncao J, Irwig L, Macaskill P, Chan SF, Richards A, Farnsworth A (2007). "Accuracy of reading liquid based cytology slides using the ThinPrep Imager compared with conventional cytology: prospective study". BMJ. 335 (7609): 31. doi:10.1136/bmj.39219.645475.55. PMC 1910624. PMID 17604301.

- International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy (IFCPC) classification. References:

-"Transformation zone (TZ) and cervical excision types". Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia.

- Jordan, J.; Arbyn, M.; Martin-Hirsch, P.; Schenck, U.; Baldauf, J-J.; Da Silva, D.; Anttila, A.; Nieminen, P.; Prendiville, W. (2008). "European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening: recommendations for clinical management of abnormal cervical cytology, part 1". Cytopathology. 19 (6): 342–354. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2303.2008.00623.x. ISSN 0956-5507. PMID 19040546. S2CID 16462929. - Zhang, Salina; McNamara, Megan; Batur, Pelin (June 2018). "Cervical Cancer Screening: What's New? Updates for the Busy Clinician". The American Journal of Medicine. 131 (6): 702.e1–702.e5. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.01.020. PMID 29408216. S2CID 46780821.

- Bettigole C (2013). "The Thousand-Dollar Pap Smear". New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (16): 1486–1487. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1307295. PMID 24131176.

- ^ Zheng, Wenxin; Fadare, Oluwole; Quick, Charles Matthew; Shen, Danhua; Guo, Donghui (2019-07-01). "History of Pap Test". Gynecologic and Obstetric Pathology, Volume 2. Springer. ISBN 978-981-13-3019-3.

- M.J. O'Dowd, E.E. Philipp, The History of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, London, Parthenon Publishing Group, 1994, p. 547.

- Pambuccian, Stefan E. (2023). "Was the Cytologic Method for Cervical Cancer Diagnosis discovered by Serendipity or by Design (hypothesis-based Research)". Sudhoffs Archiv. 107 (1): 55–83. doi:10.25162/sar-2023-0004. ISSN 2366-2352.

- Diamantis A, Magiorkinis E, Androutsos G (Jul 2010). "What's in a name? Evidence that Papanicolaou, not Babeș, deserves credit for the Pap test". Diagnostic Cytopathology. 38 (7): 473–6. doi:10.1002/dc.21226. PMID 19813255. S2CID 37757448.

- Papanicolaou, George N.; Traut, Herbert F. (1941). "The Diagnostic Value of Vaginal Smears in Carcinoma of the Uterus**This study has been aided by the Commonwealth Fund. Presented before the New York Obstetrical Society, March 11, 1941". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 42 (2): 193–206. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(16)40621-6. ISSN 0002-9378.

- Krunger, TF; Botha, MH (2007). Clinical gynaecology (3 ed.). South Africa: Juta. p. 23. ISBN 9780702173059. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- Bewtra, Chhanda; Pathan, Muhammad; Hashish, Hisham (2003-10-01). "Abnormal Pap smears with negative follow-up biopsies: Improving cytohistologic correlations". Diagnostic Cytopathology. 29 (4): 200–202. doi:10.1002/dc.10329. ISSN 1097-0339. PMID 14506671. S2CID 40202036.

- "Cervical cancer screening". www.cancer.org.au. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- "Cervical Screening". Australian Government Department of Health. 15 August 2019. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- Cancer Institute of NSW. "Do I need to pay for my cervical screen". Cancer Institute NSW.

- Chen, Y-Y; You, S-L; Chen, C-A; Shih, L-Y; Koong, S-L; Chao, K-Y; Hsiao, M-L; Hsieh, C-Y; Chen, C-J (2009-07-07). "Effectiveness of national cervical cancer screening programme in Taiwan: 12-year experiences". British Journal of Cancer. 101 (1): 174–177. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605139. ISSN 0007-0920. PMC 2713714. PMID 19536091.

- Chen, M.-J.; Wu, C.-Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, Y.-W. (2018-10-01). "HPV Vaccination and Cervical Cancer Screening in Taiwan". Journal of Global Oncology. 4 (Supplement 2): 235s. doi:10.1200/jgo.18.94300. ISSN 2378-9506.

- Fang-Hsin Leea; Chung-Yi Lic; Hsiu-Hung Wanga; Yung-Mei Yang (2013). "The utilization of Pap tests among different female medical personnel: A nationwide study in Taiwan". Preventive Medicine. 56 (6): 406–409. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.03.001. PMID 23524115.

- "Knowledge of Cervical Cancer Screening among Women". iprojectmaster.com. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- Peterson NB, Murff HJ, Cui Y, Hargreaves M, Fowke JH (Jul–Aug 2008). "Papanicolaou testing among women in the southern United States". Journal of Women's Health. 17 (6): 939–946. doi:10.1089/jwh.2007.0576. PMC 2942751. PMID 18582173.

- "Cervical screening (smear testing) | Health Information | Bupa UK". www.bupa.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- "About cervical screening". Jo's Cervical Cancer Trust. 2013-08-30. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ OB-GYN 101: Introductory Obstetrics & Gynecology > Coccoid Bacteria Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine by Michael Hughey Hughey at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. Retrieved Feb 2014.

External links

- The Pap Test: Questions and Answers — from the U.S.'s National Cancer Institute

- MedlinePlus: Cervical Cancer Prevention/Screening — from MedlinePlus

- NHS Cervical Screening Programme — from the UK's National Health Service

- Cervical cancer screening information – from Cancer Research UK

- Pap Smear – from Lab Tests Online

- Pap Smear — from eMedicineHealth

- PapScreen – Australian information about Pap tests (or Pap smears)

- Canadian Guidelines for Cervical Cancer Screening – Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada

| Human papillomavirus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related diseases |

| ||||||

| Vaccine | |||||||

| Screening |

| ||||||

| Colposcopy |

| ||||||

| History | |||||||

| Tests and procedures involving the female reproductive system | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gynecological surgery | |||||||||||

| Ovaries | |||||||||||

| Fallopian tubes | |||||||||||

| Uterus |

| ||||||||||

| Vagina | |||||||||||

| Vulva | |||||||||||

| Medical imaging | |||||||||||