Parahyangan (Preanger) or Priangan (Sundanese script: ᮕᮛᮠᮡᮍᮔ᮪) is a cultural and mountainous region in West Java province on the Indonesian island of Java. Covering a little less than one-sixth of Java, it is the heartland of Sundanese people and their culture. It is bordered to the West by Banten province, to the North by the northern coast region of Subang, Cirebon, and Indramayu (former residencies of Batavia and Cheribon), to the east by Central Java province (former residencies of Banyumas and Pekalongan), and to the south by the Indian Ocean.

Etymology

The name "Parahyangan" has its origins in Sundanese words that mean "the abode of hyangs (gods)". Parahyangan is a mountainous region, and ancient Indonesians believed that the gods resided on the mountaintops.

A Sundanese legend of Sangkuriang contains the memory of the prehistoric ancient lake in the Bandung basin highland, which suggests that the Sundanese had already inhabited the region since the Stone Age era. Another popular Sundanese proverb and legend mentioned about the creation of Parahyangan highlands is: "When the hyangs (gods) were smiling, the land of Parahyangan was created".

The train serving Jakarta and Bandung was called Kereta Api Parahyangan (lit. 'the Parahyangan train'). Since April 2010, it is merged with Argo Gede to become Argo Parahyangan.

Mapping of Sundanese Culture

The Sundanese cultural area in the western part of Java can be divided into several parts, which consist of:

- Banten Sundanese; contained the Sundanese cultural area in the west (Banten and also Lampung).

- Parahyangan Sundanese; contained the Sundanese culture in the central and southern highlands.

- Central Javan Sundanese; contained Sundanese culture in the east (e.g. Brebes, Cilacap), located within the province of Central Java.

- Northern Coast Sundanese (including Cirebon & Indramayu); contained Sundanese culture on the northern lowlands and coasts of western Java.

History

The region has been home to early humans since the prehistoric era (at least since 9,500 BCE). There have been some prehistoric archaeological findings of early human settlements, in Pawon cave in the Padalarang karst area, West of Bandung, and around the old lake of Bandung.

The ruins of the Bojongmenje temple were discovered in the Rancaekek area, Bandung Regency, east of Bandung. The temple is estimated to be dated from the early 7th century CE, around the same period — or even earlier than the Dieng temples of Central Java.

The oldest written historical reference to the Parahyangan region dates back to circa 14th century, found in Cikapundung inscription, where the region was one of the settlements within the Kingdom of Pajajaran. Parahyangan is a part of the former Sunda Kingdom. The inland mountainous region of Parahyangan was considered sacred in the Sunda Wiwitan beliefs. The kabuyutan or mandala (sacred sanctuary) of Jayagiri was mentioned in ancient Sundanese texts and is located somewhere in Parahyangan highlands, probably north of modern-day Bandung on the slopes of Mount Tangkuban Perahu.

After the fall of the Sunda Kingdom in the 16th century, Parahyangan was administered by the nobles and aristocrats of Cianjur, Sumedang, and Ciamis, centered in Sumedang Larang Kingdom. These princes claimed as the rightful heir and descendants of the Sunda kings lineage, King Siliwangi. Although the dominant power at that time was held by Banten and Cirebon Sultanates, the Sundanese aristocrats of Parahyangan highland enjoyed relatively internal freedom and autonomy.

In 1617, Sultan Agung of Mataram launched a military campaign throughout Java and vassalized the Sultanate of Cirebon. In 1618, Mataram troops conquered Ciamis and Sumedang and ruled most of the Parahyangan region. In 1630 Sultan Agung deported the native population of Parahyangan after he quashed rebellions in the area. The Mataram Sultanate was involved in a power struggle with the Dutch East India Company (VOC) centered in Batavia. Mataram was gradually weakened later through a struggle for succession of Javanese princes and Dutch involvements in internal Mataram court affairs. To secure their positions, later Mataram kings had made significant concessions with the VOC and had given up many of its lands originally acquired by Sultan Agung, including the Parahyangan. Since the early 18th century, the Parahyangan was under Dutch rule.

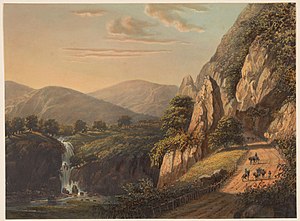

The area was known as De Preanger during the Dutch colonial period. Its capital was initially located in Tjiandjoer (Cianjur) and later moved to Bandung which gradually developed into an important settlement. By the 19th century, the Dutch had established its hold over most of Java. Moreover, through the construction of Daendels' Java Great Post Road that connected the Preanger plantation area with the port of Batavia and many other parts of Java, the Preanger was open for investment, exploitation, and business. Preanger Regencies Residency, which was founded in 1818, became an essential and productive plantation area during the Dutch East Indies era that produced coffee, tea, quinine, and many cash crops that benefited many wealthy Dutch plantation owners. The Java coffee, promoted worldwide by the Dutch, was the coffee grown in Preanger. In the early 20th century, Bandung grew into a significant settlement and a planned city. The pre-war Bandung was designed as the new capital of the Dutch East Indies, although World War II brought this plan to an end. After Indonesian independence, the Parahyangan is considered the romantic historical name for the mountainous region of West Java surrounding Bandung.

Geography

Bodebek Purwasuka Ciayumajakuning West Parahyangan Central Parahyangan East Parahyangan

The area of Parahyangan Tengah (Central Parahyangan) covers the following regencies (kabupaten), together with the independent cities of Bandung and Cimahi, which are geographically within these regencies although administratively independent.

- Bandung

- West Bandung (Bandung Barat)

- Subang (southern part)

- Garut (northern part)

- Purwakarta (southern part)

- Sumedang

Other than central Parahyangan, there is also an area known as Parahyangan Timur (Eastern Parahyangan). Together with the independent cities of Tasikmalaya and Banjar, which are geographically within these regencies although administratively independent, this area covers the regencies of:

- Garut (southern part)

- Ciamis

- Tasikmalaya

- Kuningan (southern part)

- Majalengka (southern part)

- Pangandaran

While in the west, the area known as Parahyangan Barat (Western Parahyangan) covers:

- Cianjur Regency

- Sukabumi Regency and City of Sukabumi

The Western Parahyangan area is occasionally mentioned as Bogor Raya (Greater Bogor) if grouped with Bogor Regency and the City of Bogor.

See also

- King Siliwangi

- Pajajaran

- Carita Parahyangan, a Sunda text on Galuh and other kingdoms of Sunda

Further reading

- Frederik De Haan, 1910, Priangan: de Preanger-Regentschappen onder het Nederlandsch bestuur tot 1811, Batavia

- A. Sabana Harjasaputra, 2004, Bupati di Priangan : kedudukan dan peranannya pada abad ke-17 - abad ke-19, Bandung

- Pusat Studi Sunda, 2004. Priangan dan kajian lainnya mengenai budaya Sunda, Bandung

- Ajip Rosidi et al., 2000, Ensiklopedi Sunda, Jakarta

References

- Lentz, Linda (2017). The Compass of Life: Sundanese Lifecycle Rituals and the Status of Muslim Women in Indonesia. Carolina Academic Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-61163-846-2.

- Stockdale, John J. (2011). Island of Java. London: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462902156.

- Oris Riswan (1 March 2014). "Tulang jari di Goa Pawon berumur 9.500 tahun lebih". Sindo News (in Indonesian).

- "An Extremely Brief Urban History of Bandung". Institute of Indonesian Architectural Historian. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- Brahmantyo, B.; Yulianto, E.; Sudjatmiko (2001). "On the geomorphological development of Pawon Cave, west of Bandung, and the evidence finding of prehistoric dwelling cave". JTM. Archived from the original on October 21, 2009. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- "Candi Bojongmenje". Perpustakaan Nasional Indonesia (in Indonesian).

- R.Teja Wulan (9 October 2010). "Prasasti Bertuliskan Huruf Sunda Kuno Ditemukan di Bandung". VOA Indonesia (in Indonesian).

- Kiernan, Ben (2008). Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500-2000. p. 142. ISBN 9780522854770.