Queen Elizabeth's Men was a playing company or troupe of actors in English Renaissance theatre. Formed in 1583 at the express command of Queen Elizabeth, it was the dominant acting company for the rest of the 1580s, as the Admiral's Men and the Lord Chamberlain's Men would be in the decade that followed.

Foundation

Since the Queen instigated the formation of the company, its inauguration is well documented by Elizabethan standards. The order came down on 10 March 1583 (new style) to Edmund Tilney, then the Master of the Revels; though Sir Francis Walsingham, head of intelligence operations for the Elizabethan court, was the official assigned to assemble the personnel. At that time the Earl of Sussex, who had been the court official in charge of the Lord Chamberlain's Men in its first Elizabethan incorporation, was nearing death. The Queen's Men assumed the same functional role in the Elizabethan theatrical landscape as the Lord Chamberlain's Men before and after them did: it was the company most directly responsible for providing entertainment at court (although other companies also performed before the Queen).

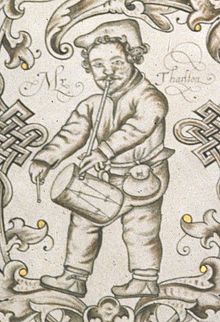

The task of convening the new troupe apparently needed Walsingham's strong arm, since it was assembled by raiding the best performers from the companies existing at the time. But it also signaled a new awareness on behalf of the Queen and the privy council of the potential for combining theatrical and espionage activities, since players frequently traveled, both nationally and internationally, and could serve the crown in multiple ways, including the collection of information useful to Walsingham's spy network. Leicester's Men, till then the leading company of the day, lost three to the new assemblage (Robert Wilson, John Laneham, and William Johnson), while Oxford's troupe lost both of its leading men, the brothers John and Laurence Dutton; Sussex's Men were pillaged of leader John Adams and star clown Richard Tarlton. Other prominent members of the new company were John Singer, William Knell and the "inimitable" John Bentley. Tarlton quickly became the star of the Queen's Men – "for a wondrous plentiful pleasant extemporal wit, he was the wonder of his time."

It has been proposed that Elizabeth had a specific political motive behind the formation of the company. Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester and Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford were using their companies of players to compete for attention and prestige at each year's Christmas festivities at Court; Elizabeth and her councillors apparently judged the competition, and the noblemen's egos, to be getting out of hand. By culling the best players in their troupes to form her own, she slapped down ambitious aristocrats and asserted her own priority.

Status

Their genesis made Queen Elizabeth's Men unique among the acting companies of the age: "The Queen's Men were a deliberately political company in origin, and their repertory appears to have followed the path no doubt pointed out for them by Sir Francis Walsingham." In the plays they acted, "one finds no conflict or disturbance that is not settled in the interests of Tudor conservatism." The political controversies that marked later companies and plays – The Isle of Dogs, The Isle of Gulls, and others – did not occur with the Queen's Men. They may, however, have run afoul of higher authorities in 1589, shortly before their dissolution, for involving themselves too vigorously in the Martin Marprelate episode by parodying Martin on the public stage.

The Queen's company was officially authorized to play at two locations in London, the Bel Savage Inn on Ludgate Hill, and the Bell Inn in Gracechurch Street, within the City near Bishopsgate in the western wall. The former was a large open-air venue, but the latter may have been enclosed. With this arrangement, Queen Elizabeth's Men may have anticipated the dual summer and winter playing sites that the King's Men achieved only a quarter-century later with the Globe and Blackfriars Theatres.

Dominance

The creation of the company took advantage of the growing versatility and professionalism of the community of actors in this era. Elizabeth's Court had had a troupe of interlude players in previous years and decades; but they were judged unsatisfactory, and the Court depended on the companies of child actors for better-quality entertainment. But as John Stow wrote of this period in his Annals (1615):

Comedians and stage-players of former times were very poor and ignorant...but being now grown very skillful and exquisite actors for all matters, they were entertained into the service of diverse great lords: out of which there were twelve of the best chosen, and...were sworn the Queen's servants and were allowed wages and liveries as Grooms of the Chamber."

The company entertained at Court primarily in the winter, and during the summer they toured the towns of the shires; they may have reached as far as Scotland in 1589. In London they were initially allowed to perform only at the Bull and Bell Inns – though in later years they may have acted at James Burbage's Theatre as well.

The number of twelve founding members is more revealing than it seems at first: Queen Elizabeth's Men was the first large company of actors in English Renaissance theatre, twice the size of its predecessors. (Sussex's Men had six members in the 1570s. When Elsinore Castle receives a troupe of touring players in Hamlet, Act II, scene ii, their number is only "four or five." The players in Sir Thomas More are "four men and a boy....") The size of the new company enabled it to act a new kind of play, built on a larger scale than ever before. In particular, the development of the history play, which was such a distinctive feature of the later 1580s and the 1590s, would not have been possible without a large company to handle the performances. The Famous Victories of Henry V (c. 1583), one of the earliest of this type of play, has twenty speaking parts in the first 500 lines; and the plays that were to follow, including Shakespeare's histories, are constructed on a similar scale. These were, in effect, the "Hollywood spectaculars" of their era, and represent a leap to a new level of complexity and professionalism; before the establishment of the Queen's Men, such plays would have been unactable. When the Queen's Men were finally supplanted at Court in the winter of 1591–92, it required an assemblage of personnel from both the Admiral's Men and Lord Strange's Men to fill their place.

An extreme instance of the above phenomenon may be found in the example of the Queen's Men's production of The True Tragedy of Richard III. By one reconstruction, four actors were required to play seven roles each, and the boy actors, unusually, also had to double roles, for the Queen's Men to fill the 68 separate roles in the play.

Decline

William Knell was killed in 1587 in a sword fight when he got into an argument with another actor of the troupe, one John Towne. Richard Tarlton died in 1588, at a time when Queen Elizabeth's Men were facing new competition from the Admiral's Men, who were playing the plays of Christopher Marlowe with Edward Alleyn in the leads. The character of the troupe also changed around this time; they were joined by John Symons and other acrobats from Lord Strange's Men. And with this different emphasis and orientation, they appear to have lost the high regard they previously enjoyed. They played only once at Court in the 1591 Christmas season, while a combination of Admiral's and Lord Strange's Men performed six times in the same period. The disruption of the 1592–93 period, when the London theatres were closed due to bubonic plague and the companies of actors struggled to survive, hit the Queen's company hard. When the actors re-organized themselves in 1594, primarily in the re-formed Lord Chamberlain's and Admiral's companies, Queen Elizabeth's Men were passé. John Singer completed his stage career with a decade with the Admiral's Men; the others toured the provinces and sold off their play books to London stationers.

(A nucleus of the company may have continued on for some years, under other names and with other patrons. Two of the Queen's Men, John Garland and Francis Henslowe, were later with Lennox's Men, under the patronage of Ludovic Stuart, 2nd Duke of Lennox; that company toured the countryside from 1604 to 1608.)

Plays

Because of the publication of some of their plays in the early 1590s, the repertory of Queen Elizabeth's Men is known to a limited degree. The following plays were acted by the company:

- The Famous Victories of Henry V

- Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay (Robert Greene)

- James IV (Robert Greene)

- King Leir

- A Looking Glass for London and England (Robert Greene and Thomas Lodge)

- The Old Wives' Tale (George Peele)

- Sir Clyomon and Sir Clamydes

- The Troublesome Reign of King John

- The True Tragedy of Richard III

Notes

- Chambers, Vol. 2, pp. 104 ff.

- McMillin; MacLean (1998) p.27

- McMillin; MacLean (1998), pp. 5, 11–12.

- Chambers, Vol. 2, p. 105.

- Gurr, pp. 28, 32.

- McMillin (1987), p. 59.

- The author of one anonymous tract of the controversy, Martin’s Months minde, That is, A Certaine report, and true description of the Death and Funeralls of Old Martin Marre-prelate, the great makebate of England, and father of the Factious, boasts that "hir maiesties men" were among those pleased to "returne the cuffe, instead of the glove, and hiss the fooles from off the stage." London: Printed by Thomas Orwin, 1589. S108299, D3.

- Gurr, pp. 119–20.

- Chambers, Vol. 2, p. 104; Halliday (1964), p. 398.

- McMillin (1987), pp. 55–60.

- For more on the relative sizes of acting companies in this era, see the entry on Sir Thomas More.

- McMillin; MacLean (1998), p. 105.

- Halliday (1964), p. 277.

References

- Chambers, E. K. The Elizabethan Stage. 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923.

- Gurr, Andrew. The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642. Third edition, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Halliday, F. E. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore, Penguin, 1964.

- McMillin, Scott. The Elizabethan Theatre and "The Book of Sir Thomas More." Ithaca, N.Y., Cornell University Press, 1987.

- McMillin, Scott, and Sally-Beth MacLean. The Queen's Men and Their Plays. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1998.