In computer graphics, the rendering equation is an integral equation in which the equilibrium radiance leaving a point is given as the sum of emitted plus reflected radiance under a geometrical optics approximation. It was simultaneously introduced into computer graphics by David Immel et al. and James Kajiya in 1986. The various realistic rendering techniques in computer graphics attempt to solve this equation.

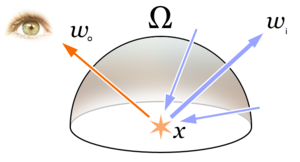

The physical basis for the rendering equation is the law of conservation of energy. Assuming that denotes radiance, we have that at each particular position and direction, the outgoing light () is the sum of the emitted light () and the reflected light (). The reflected light itself is the sum from all directions of the incoming light () multiplied by the surface reflection and cosine of the incident angle.

Equation form

The rendering equation may be written in the form

where

- is the total spectral radiance of wavelength directed outward along direction at time , from a particular position

- is the location in space

- is the direction of the outgoing light

- is a particular wavelength of light

- is time

- is emitted spectral radiance

- is reflected spectral radiance

- is an integral over

- is the unit hemisphere centered around containing all possible values for where

- is the bidirectional reflectance distribution function, the proportion of light reflected from to at position , time , and at wavelength

- is the negative direction of the incoming light

- is spectral radiance of wavelength coming inward toward from direction at time

- is the surface normal at

- is the weakening factor of outward irradiance due to incident angle, as the light flux is smeared across a surface whose area is larger than the projected area perpendicular to the ray. This is often written as .

Two noteworthy features are: its linearity—it is composed only of multiplications and additions, and its spatial homogeneity—it is the same in all positions and orientations. These mean a wide range of factorings and rearrangements of the equation are possible. It is a Fredholm integral equation of the second kind, similar to those that arise in quantum field theory.

Note this equation's spectral and time dependence — may be sampled at or integrated over sections of the visible spectrum to obtain, for example, a trichromatic color sample. A pixel value for a single frame in an animation may be obtained by fixing motion blur can be produced by averaging over some given time interval (by integrating over the time interval and dividing by the length of the interval).

Note that a solution to the rendering equation is the function . The function is related to via a ray-tracing operation: The incoming radiance from some direction at one point is the outgoing radiance at some other point in the opposite direction.

Applications

Solving the rendering equation for any given scene is the primary challenge in realistic rendering. One approach to solving the equation is based on finite element methods, leading to the radiosity algorithm. Another approach using Monte Carlo methods has led to many different algorithms including path tracing, photon mapping, and Metropolis light transport, among others.

Limitations

Although the equation is very general, it does not capture every aspect of light reflection. Some missing aspects include the following:

- Transmission, which occurs when light is transmitted through the surface, such as when it hits a glass object or a water surface,

- Subsurface scattering, where the spatial locations for incoming and departing light are different. Surfaces rendered without accounting for subsurface scattering may appear unnaturally opaque — however, it is not necessary to account for this if transmission is included in the equation, since that will effectively include also light scattered under the surface,

- Polarization, where different light polarizations will sometimes have different reflection distributions, for example when light bounces at a water surface,

- Phosphorescence, which occurs when light or other electromagnetic radiation is absorbed at one moment and emitted at a later moment, usually with a longer wavelength (unless the absorbed electromagnetic radiation is very intense),

- Interference, where the wave properties of light are exhibited,

- Fluorescence, where the absorbed and emitted light have different wavelengths,

- Non-linear effects, where very intense light can increase the energy level of an electron with more energy than that of a single photon (this can occur if the electron is hit by two photons at the same time), and emission of light with higher frequency than the frequency of the light that hit the surface suddenly becomes possible, and

- Doppler effect, where light that bounces off an object moving at a very high speed will get its wavelength changed: if the light bounces off an object that is moving towards it, the light will be blueshifted and the photons will be packed more closely so the photon flux will be increased; if it bounces off an object moving away from it, it will be redshifted and the photon flux will be decreased. This effect becomes apparent only at speeds comparable to the speed of light, which is not the case for most rendering applications.

For scenes that are either not composed of simple surfaces in a vacuum or for which the travel time for light is an important factor, researchers have generalized the rendering equation to produce a volume rendering equation suitable for volume rendering and a transient rendering equation for use with data from a time-of-flight camera.

References

- Immel, David S.; Cohen, Michael F.; Greenberg, Donald P. (1986). "A radiosity method for non-diffuse environments" (PDF). In David C. Evans; RussellJ. Athay (eds.). SIGGRAPH '86. Proceedings of the 13th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques. pp. 133–142. doi:10.1145/15922.15901. ISBN 978-0-89791-196-2. S2CID 7384510.

- Kajiya, James T. (1986). "The rendering equation" (PDF). In David C. Evans; RussellJ. Athay (eds.). SIGGRAPH '86. Proceedings of the 13th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques. pp. 143–150. doi:10.1145/15922.15902. ISBN 978-0-89791-196-2. S2CID 9226468.

- Watt, Alan; Watt, Mark (1992). "12.2.1 The path tracing solution to the rendering equation". Advanced Animation and Rendering Techniques: Theory and Practice. Addison-Wesley Professional. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-201-54412-1.

- Owen, Scott (September 5, 1999). "Reflection: Theory and Mathematical Formulation". Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- Kajiya, James T.; Von Herzen, Brian P. (1984), "Ray tracing volume densities", ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics, 18 (3): 165–174, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.128.3394, doi:10.1145/964965.808594

- Smith, Adam M.; Skorupski, James; Davis, James (2008). Transient Rendering (PDF) (Technical report). UC Santa Cruz. UCSC-SOE-08-26.

External links

- Lecture notes from Stanford University course CS 348B, Computer Graphics: Image Synthesis Techniques

denotes

denotes  ) is the sum of the emitted light (

) is the sum of the emitted light ( ) and the reflected light (

) and the reflected light ( ). The reflected light itself is the sum from all directions of the incoming light (

). The reflected light itself is the sum from all directions of the incoming light ( ) multiplied by the surface reflection and

) multiplied by the surface reflection and

is the total

is the total  directed outward along direction

directed outward along direction  at time

at time  , from a particular position

, from a particular position

is

is  is

is  is an

is an

containing all possible values for

containing all possible values for  where

where

is the

is the  is spectral radiance of wavelength

is spectral radiance of wavelength  is the weakening factor of outward

is the weakening factor of outward  .

. may be sampled at or integrated over sections of the

may be sampled at or integrated over sections of the

is related to

is related to