| Sicilian | |

|---|---|

| sicilianu | |

| Native to | Italy |

| Region | Sicily |

| Ethnicity | Sicilians |

| Native speakers | 4.7 million (2002) |

| Language family | Indo-European |

| Dialects | |

| Official status | |

| Recognised minority language in | Sicily (limited recognition) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | scn |

| ISO 639-3 | scn |

| Glottolog | sici1248 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-re & -rf (mainland 51-AAA-rc & -rd) |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. | |

| This article is part of the series on the |

| Sicilian language |

|---|

| History |

| Literature and writers |

| Linguistics |

| Organisations |

Sicilian (Sicilian: sicilianu, Sicilian: [sɪ(t)ʃɪˈljaːnu]; Italian: siciliano) is a Romance language that is spoken on the island of Sicily and its satellite islands. It belongs to the broader Extreme Southern Italian language group (in Italian italiano meridionale estremo).

Ethnologue (see below for more detail) describes Sicilian as being "distinct enough from Standard Italian to be considered a separate language", and it is recognized as a minority language by UNESCO. It has been referred to as a language by the Sicilian Region. It has the oldest literary tradition of the Italo-Romance languages. A version of the UNESCO Courier is also available in Sicilian.

Status

Sicilian is spoken by most inhabitants of Sicily and by emigrant populations around the world. The latter are found in the countries that attracted large numbers of Sicilian immigrants during the course of the past century or so, especially the United States (specifically in the Gravesend and Bensonhurst neighborhoods of Brooklyn, New York City, and in Buffalo and Western New York State), Canada (especially in Montreal, Toronto and Hamilton), Australia, Venezuela and Argentina. During the last four or five decades, large numbers of Sicilians were also attracted to the industrial zones of Northern Italy and areas of the European Union.

Although the Sicilian language does not have official status (including in Sicily), in addition to the standard Sicilian of the medieval Sicilian school, academics have developed a standardized form. Such efforts began in the mid-19th century when Vincenzo Mortillaro published a comprehensive Sicilian language dictionary intended to capture the language universally spoken across Sicily in a common orthography. Later in the century, Giuseppe Pitrè established a common grammar in his Grammatica Siciliana (1875). Although it presents a common grammar, it also provides detailed notes on how the sounds of Sicilian differ across dialects.

In the 20th century, researchers at the Centro di studi filologici e linguistici siciliani developed an extensive descriptivist orthography which aims to represent every sound in the natural range of Sicilian accurately. This system is also used extensively in the Vocabolario siciliano and by Gaetano Cipolla in his Learn Sicilian series of textbooks and by Arba Sicula in its journal.

In initially 2017, with an updated version in 2024 the nonprofit organisation Cademia Siciliana created an orthographic proposal to help to normalise the language's written form. This orthography was used by the organisation in their collaboration with Google to bring the Sicilian Language to Google Translate.

The autonomous regional parliament of Sicily has legislated Regional Law No. 9/2011 to encourage the teaching of Sicilian at all schools, but inroads into the education system have been slow. The CSFLS created a textbook "Dialektos" to comply with the law but does not provide an orthography to write the language. In Sicily, it is taught only as part of dialectology courses, but outside Italy, Sicilian has been taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Brooklyn College and Manouba University. Since 2009, it has been taught at the Italian Charities of America, in New York City (home to the largest Sicilian speaking community outside of Sicily and Italy) and it is also preserved and taught by family association, church organisations and societies, social and ethnic historical clubs and even Internet social groups, mainly in Gravesend and Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. On 15 May 2018, the Sicilian Region once again mandated the teaching of Sicilian in schools and referred to it as a language, not a dialect, in official communication. The language is officially recognized in the municipal statutes of some Sicilian towns, such as Caltagirone and Grammichele, in which the "inalienable historical and cultural value of the Sicilian language" is proclaimed. Furthermore, the Sicilian language would be protected and promoted under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML). Although Italy has signed the treaty, the Italian Parliament has not ratified it. It is not included in Italian Law No. 482/1999 although some other minority languages of Sicily are.

Ethnologue report

Other names

Alternative names of Sicilian are Calabro-Sicilian, sicilianu, and sìculu. The first term refers to the fact that a form of Sicilian is spoken in southern Calabria, particularly in the province of Reggio Calabria. The other two are names for the language in Sicily itself: specifically, the term sìculu originally describes one of the larger prehistoric groups living in Sicily (the Italic Sicels or Siculi) before the arrival of Greeks in the 8th century BC (see below). It can also be used as a prefix to qualify or to elaborate further on the origins of a person, for example: Siculo-American (sìculu-miricanu) or Siculo-Australian.

Dialects

As a language, Sicilian has its own dialects in the following main groupings:

- Western Sicilian (Palermitano in Palermo, Trapanese in Trapani, Central-Western Agrigentino in Agrigento)

- Central Metafonetic (in the central part of Sicily that includes some areas of the provinces of Caltanissetta, Messina, Enna, Palermo and Agrigento)

- Southeast Metafonetic (in the Province of Ragusa and the adjoining area within the Province of Syracuse)

- Ennese (in the Province of Enna)

- Eastern Non-Metafonetic (in the area including the Metropolitan City of Catania, the second largest city in Sicily, as Catanese, and the adjoining area within the Province of Syracuse)

- Messinese (in the Metropolitan City of Messina, the third largest city in Sicily)

- Eoliano (in the Aeolian Islands)

- Pantesco (on the island of Pantelleria)

- Reggino (in the Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria, especially on the Scilla–Bova line, and excluding the areas of Locri and Rosarno, which represent the first isogloss that divide Sicilian from the continental varieties).

History

First let us turn our attention to the language of Sicily, since the Sicilian vernacular seems to hold itself in higher regard than any other, because all the poetry written by the Italians is called "Sicilian"...

— Dante Alighieri, De Vulgari Eloquentia, Lib. I, XII, 2

Latin 2,792 (55.84%)

Greek 733 (14.66%)

Spanish 664 (13.28%)

French 318 (6.36%)

Arabic 303 (6.06%)

Catalan 107 (2.14%)

Occitan 103 (1.66%)

Early influences

Because Sicily is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea and many peoples have passed through it (Phoenicians, Ancient Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Jews, Byzantine Greeks, Arabs, Normans, Swabians, Spaniards, Austrians, Italians), Sicilian displays a rich and varied influence from several languages in its lexical stock and grammar. These languages include Latin (as Sicilian is a Romance language itself), Ancient Greek, Byzantine Greek, Spanish, Norman, Lombard, Hebrew, Catalan, Occitan, Arabic and Germanic languages, and the languages of the island's aboriginal Indo-European and pre-Indo-European inhabitants, known as the Sicels, Sicanians and Elymians. The very earliest influences, visible in Sicilian to this day, exhibit both prehistoric Mediterranean elements and prehistoric Indo-European elements, and occasionally a blending of both.

Before the Roman conquest (3rd century BC), Sicily was occupied by various populations. The earliest of these populations were the Sicanians, considered to be autochthonous. The Sicels and the Elymians arrived between the second and first millennia BC. These aboriginal populations in turn were followed by the Phoenicians (between the 10th and 8th centuries BC) and the Greeks. The heavy Greek-language influence remains strongly visible, while the influences from the other groups are smaller and less obvious. What can be stated with certainty is that in Sicilian remain pre-Indo-European words of an ancient Mediterranean origin, but one cannot be more precise than that: of the three main prehistoric groups, only the Sicels were known to be Indo-European with a degree of certainty, and their speech is likely to have been closely related to that of the Romans.

Stratification

The following table, listing words for "twins", illustrates the difficulty linguists face in tackling the various substrata of the Sicilian language.

| Stratum | Word | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Modern | giameddi | Italian gemelli |

| Medieval | bizzuni, vuzzuni | Old French or Catalan bessons |

| binelli | Ligurian beneli | |

| Ancient | èmmuli | Latin gemelli |

| cucchi | Latin copula | |

| minzuddi | Latin medii | |

| ièmiddi, ièddimi | Ancient Greek δίδυμοι dídymoi |

A similar qualifier can be applied to many of the words that appear in this article. Sometimes it may be known that a particular word has a prehistoric derivation, but it is not known whether the Sicilians inherited it directly from the indigenous populations, or whether it came via another route. Similarly, it might be known that a particular word has a Greek origin but it is not known from which Greek period the Sicilians first used it (ancient Magna Grecia or the Byzantine period), or once again, whether the particular word may even have come to Sicily via another route. For instance, by the time the Romans had occupied Sicily, the Latin language had made its own borrowings from Greek.

Pre-classical period

The words with a prehistoric Mediterranean derivation often refer to plants native to the Mediterranean region or to other natural features. Bearing in mind the qualifiers mentioned above (alternative sources are provided where known), examples of such words include:

- alastra – "spiny broom" (a thorny, prickly plant native to the Mediterranean region; but also Greek kélastron and may in fact have penetrated Sicilian via one of the Gaulish languages)

- ammarrari – "to dam or block a canal or running water" (but also Spanish embarrar "to muddy")

- calancuni – "ripples caused by a fast running river"

- calanna – "landslide of rocks" (cf. Greek χαλάω (khaláō) "loosen, drop", verb borrowed into Latin, widespread in Romance languages)

- racioppu – "stalk or stem of a fruit etc." (ancient Mediterranean word rak)

- timpa – "crag, cliff" (but also Greek týmba, Latin tumba and Catalan timba).

There are also Sicilian words with an ancient Indo-European origin that do not appear to have come to the language via any of the major language groups normally associated with Sicilian, i.e. they have been independently derived from a very early Indo-European source. The Sicels are a possible source of such words, but there is also the possibility of a cross-over between ancient Mediterranean words and introduced Indo-European forms. Some examples of Sicilian words with an ancient Indo-European origin:

- dudda – "mulberry" (similar to Indo-European *h₁rowdʰós, Romanian dudă and Welsh rhudd "red, crimson")

- scrozzu – "not well developed" (similar to Lithuanian su-skurdes with a similar meaning and Old High German scurz "short")

- sfunnacata – "multitude, vast number" (from Indo-European *h₁wed- "water").

Greek influences

The following Sicilian words are of a Greek origin (including some examples where it is unclear whether the word is derived directly from Greek, or via Latin):

- babbiari – "to fool around" (from babázō, which also gives the Sicilian words: babbazzu and babbu "stupid"; but also Latin babulus and Spanish babieca)

- bucali – "pitcher" (from baúkalion) (cognate of Maltese buqar, Italian boccale)

- bùmmulu – "water receptacle" (from bómbylos; but also Latin bombyla) (cognate of Maltese bomblu)

- cartedda – "basket" (from kártallos; but also Latin cartellum)

- carusu – "boy" (from koûros; but also Latin carus "dear", Sanskrit caruh "amiable")

- casèntaru – "earthworm" (from gês énteron)

- cirasa – "cherry" (from kerasós; but also Latin cerasum) (cognate of Maltese ċirasa)

- cona – "icon, image, metaphor" (from eikóna; but also Latin icona)

- cuddura – type of bread (from kollýra; but Latin collyra)

- grasta – "flower pot" (from gástra; but also Latin gastra)

- naca – "cradle" (from nákē)

- ntamari – "to stun, amaze" (from thambéō)

- pistiari – "to eat" (from esthíō)

- tuppiàri – "to knock" (from týptō)

- nìcaru - "small, young" (from mīkkós)

Germanic influences

From 476 to 535, the Ostrogoths ruled Sicily, although their presence apparently did not affect the Sicilian language. The few Germanic influences to be found in Sicilian do not appear to originate from this period. One exception might be abbanniari or vanniari "to hawk goods, proclaim publicly", from Gothic bandwjan "to give a signal". Also possible is schimmenti "diagonal" from Gothic slimbs "slanting". Other sources of Germanic influences include the Hohenstaufen rule of the 13th century, words of Germanic origin contained within the speech of 11th-century Normans and Lombard settlers, and the short period of Austrian rule in the 18th century.

Many Germanic influences date back to the time of the Swabian kings (amongst whom Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor enjoyed the longest reign). Some of the words below are "reintroductions" of Latin words (also found in modern Italian) that had been Germanicized at some point (e.g. vastāre in Latin to guastare in modern Italian). Words that probably originate from this era include:

- arbitriari – "to work in the fields" (from arbeit; but other possible Latin derivations)

- vardari – "to watch over" (from wardon)

- guddefi – "forest, woods" (from wald; note the resemblance to Anglo-Saxon wudu)

- guzzuniari – "to wag, as in a tail" (from hutsen)

- lancedda (terracotta jug for holding water; from Old High German lagella)

- sparagnari – "to save money" (from Old High German sparen)

Arabic influence

In 535, Justinian I made Sicily a Byzantine province, which returned the Greek language to a position of prestige, at least on an official level. At this time the island could be considered a border zone with moderate levels of bilingualism: Latinisation was mostly concentrated in western Sicily, largely among the upper class, whereas Eastern Sicily remained predominantly Greek. As the power of the Byzantine Empire waned, Sicily was progressively conquered by Saracens from Ifriqiya, from the mid 9th to mid 10th centuries. The Emirate of Sicily persisted long enough to develop a distinctive local variety of Arabic, Siculo-Arabic (at present extinct in Sicily but surviving as the Maltese language). Its influence is noticeable in around 300 Sicilian words, most of which relate to agriculture and related activities. This is understandable because of the Arab Agricultural Revolution; the Saracens introduced to Sicily their advanced irrigation and farming techniques and a new range of crops, nearly all of which remain endemic to the island to this day.

Some words of Arabic origin:

- azzizzari – "to embellish" (عزيز ʿazīz "precious, beautiful") (Cognate of Maltese għażiż, meaning "dear")

- babbaluciu – "snail" (from babūš, Tunisian babūša; but also Greek boubalákion. Cognate of Maltese bebbuxu)

- burnia – "jar" (برنية burniya; but also Latin hirnea)

- cafisu (measure for liquids; from Tunisian قفيز qafīz)

- cassata (Sicilian ricotta cake; from قشطة qišṭa, chiefly North African; but Latin caseata "something made from cheese". Cognate of Maltese qassata)

- gèbbia – artificial pond to store water for irrigation (from Tunisian جابية jābiya. Cognate of Maltese ġiebja and Spanish aljibe)

- giuggiulena – "sesame seed" (from Tunisian جلجلان jiljlān or juljulān. Cognate of Maltese ġunġlien or ġulġlien and Spanish ajonjolí).

- ràisi – "leader" (رئيس raʾīs. Cognate of Maltese ras "head")

- saia – "canal" (from ساقية sāqiya. Cognate of Spanish acequia Maltese saqqajja)

- zaffarana – "saffron" (type of plant whose flowers are used for medicinal purposes and in Sicilian cooking; from زعفران zaʿfarān. Cognate of Maltese żagħfran and English Saffron)

- zàgara – "blossom" (زهرة zahra. Cognate of Maltese żahar and Spanish azahar)

- zibbibbu – "muscat of Alexandria" (type of dried grape; زبيب zabīb. Cognate of Maltese żbib)

- zuccu – "market" (from سوق sūq; but also Aragonese soccu and Spanish zoque. Cognate of Maltese suq)

- Bibbirria (the northern gate of Agrigento; باب الرياح bāb ar-riyāḥ "Gate of the Winds").

- Gisira – "island" (جَزِيرَة jazīra. Cognate of Maltese gżira) (archaic)

Throughout the Islamic epoch of Sicilian history, a significant Greek-speaking population remained on the island and continued to use the Greek language, or most certainly a variant of Greek influenced by Tunisian Arabic. What is less clear is the extent to which a Latin-speaking population survived on the island. While a form of Vulgar Latin clearly survived in isolated communities during the Islamic epoch, there is much debate as to the influence it had (if any) on the development of the Sicilian language, following the re-Latinisation of Sicily (discussed in the next section).

Linguistic developments in the Middle Ages

By AD 1000, the whole of what is today Southern Italy, including Sicily, was a complex mix of small states and principalities, languages and religions. The whole of Sicily was controlled by Saracens, at the elite level, but the general population remained a mix of Muslims and Christians who spoke Greek, Latin or Siculo-Arabic. The far south of the Italian peninsula was part of the Byzantine empire although many communities were reasonably independent from Constantinople. The Principality of Salerno was controlled by Lombards (or Langobards), who had also started to make some incursions into Byzantine territory and had managed to establish some isolated independent city-states. It was into this climate that the Normans thrust themselves with increasing numbers during the first half of the 11th century.

Norman and French influence

When the two most famous of Southern Italy's Norman adventurers, Roger of Hauteville and his brother, Robert Guiscard, began their conquest of Sicily in 1061, they already controlled the far south of Italy (Apulia and Calabria). It took Roger 30 years to complete the conquest of Sicily (Robert died in 1085). In the aftermath of the Norman conquest of Sicily, the reintroduction of Latin in Sicily had begun, and some Norman words would be absorbed, that would be accompanied with an additional wave of Parisian French loanwords during the rule of Charles I from the Capetian House of Anjou in the 13th century.

- accattari – "to buy" (from Norman French acater, French acheter; but there are different varieties of this Latin etymon in the Romania, cf. Old Occitan acaptar)

- ammucciari – "to hide" (Old Norman French muchier, Norman French muchi/mucher, Old French mucier; but also Greek mychós)

- bucceri/vucceri "butcher" (from Old French bouchier)

- custureri – "tailor" (Old French cousturier; Modern French couturier)

- firranti – "grey" (from Old French ferrant)

- foddi – "mad" (Old French fol, whence French fou)

- giugnettu – "July" (Old French juignet)

- ladiu/laiu – "ugly" (Old French laid)

- largasìa – "generosity" (largesse; but also Spanish largueza)

- puseri – "thumb" (Old French pochier)

- racina – "grape" (Old French, French raisin)

- raggia – "anger" (Old French, French rage)

- trippari – "to hop, skip" (Norman French triper)

Other Gallic influences

The Northern Italian influence is of particular interest. Even to the present day, Gallo-Italic of Sicily exists in the areas where the Northern Italian colonies were the strongest, namely Novara, Nicosia, Sperlinga, Aidone and Piazza Armerina. The Siculo-Gallic dialect did not survive in other major Italian colonies, such as Randazzo, Caltagirone, Bronte and Paternò (although they influenced the local Sicilian vernacular). The Gallo-Italic influence was also felt on the Sicilian language itself, as follows:

- sòggiru – "father-in-law" (from suoxer)

- cugnatu – "brother-in-law" (from cognau) (cognate of Maltese kunjat)

- figghiozzu – "godson" (from figlioz) (cognate of Maltese filjozz)

- orbu/orvu – blind (from orb)

- arricintari – "to rinse" (from rexentar)

- unni – "where" (from ond)

- the names of the days of the week:

- luni – "Monday" (from lunes)

- marti – "Tuesday" (from martes)

- mèrcuri – "Wednesday" (from mèrcor)

- jovi – "Thursday" (from juovia)

- vènniri – "Friday" (from vènner)

Occitan influence

The origins of another Romance influence, that of Occitan, had three reasons:

- The Normans made San Fratello a garrison town in the early years of the occupation of the northeastern corner of Sicily. To this day (in ever decreasing numbers) a Siculo-Gallic dialect is spoken in San Fratello that is clearly influenced by Occitan, which leads to the conclusion that a significant number in the garrison came from that part of France. This may well explain the dialect spoken only in San Fratello, but it does not wholly explain the diffusion of many Occitan words into the Sicilian language. On that point, there are two other possibilities:

- Some Occitan words have entered the language during the regency of Margaret of Navarre between 1166 and 1171, when her son, William II of Sicily, succeeded to the throne at the age of 12. Her closest advisers, entourage and administrators were from the south of France, and many Occitan words entered the language during this period.

- The Sicilian School of poetry was strongly influenced by the Occitan of the troubadour tradition. This element is deeply embedded in Sicilian culture: for example, the tradition of Sicilian puppetry (òpira dî pupi) and the tradition of the cantastorie (literally "story-singers"). Occitan troubadours were active during the reign of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, and some Occitan words would have passed into the Sicilian language via this route.

Some examples of Sicilian words derived from Occitan:

- addumari – "to light, to turn something on" (from allumar)

- aggrifari – "to kidnap, abduct" (from grifar; but also German greiffen)

- banna – "side, place" (from banda) (cognate of Maltese banda "side")

- burgisi – "landowner, citizen" (from borges)

- lascu – "sparse, thin, infrequent" (from lasc)(cognate of Maltese laxk "loose")

- pariggiu – "equal" (from paratge). (cognate of Maltese pariġġ "equal, as")

Sicilian School of Poetry

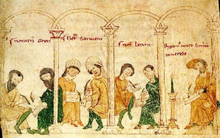

Main article: Sicilian SchoolIt was during the reign of Frederick II (or Frederick I of Sicily) between 1198 and 1250, with his patronage of the Sicilian School, that Sicilian became the first of the modern Italic languages to be used as a literary language. The influence of the school and the use of Sicilian itself as a poetic language was acknowledged by the two great Tuscan writers of the early Renaissance period, Dante and Petrarch. The influence of the Sicilian language should not be underestimated in the eventual formulation of a lingua franca that was to become modern Italian. The victory of the Angevin army over the Sicilians at Benevento in 1266 not only marked the end of the 136-year Norman-Swabian reign in Sicily but also effectively ensured that the centre of literary influence would eventually move from Sicily to Tuscany. While Sicilian, as both an official and a literary language, would continue to exist for another two centuries, the language would soon follow the fortunes of the kingdom itself in terms of prestige and influence.

Catalan influence

Following the Sicilian Vespers of 1282, the kingdom came under the influence of the Crown of Aragon, and the Catalan language (and the closely related Aragonese) added a new layer of vocabulary in the succeeding century. For the whole of the 14th century, both Catalan and Sicilian were the official languages of the royal court. Sicilian was also used to record the proceedings of the Parliament of Sicily (one of the oldest parliaments in Europe) and for other official purposes. While it is often difficult to determine whether a word came directly from Catalan (as opposed to Occitan), the following are likely to be such examples:

- addunàrisi – "to notice, realise" (from adonar-se) (cognate of Maltese induna)

- affruntàrisi – "to be embarrassed" (from afrontar-se)

- arruciari – "to moisten, soak" (from arruixar) (cognate of Maltese raxx "to shower")

- criscimonia – "growth, development" (from creiximoni)

- muccaturi – "handkerchief" (from mocador; but also French mouchoir) (cognate of Maltese maktur)

- priàrisi – "to be pleased" (from prear-se)

- taliari – "to look at somebody/something" (from talaiar; but also Arabic طليعة ṭalīʿa).

- fardali – "apron" (from faldar) (cognate of Maltese fardal)

Spanish period to the modern age

By the time the crowns of Castille and Aragon were united in the late 15th century, the Hispanicisation and Italianisation of written Sicilian in the parliamentary and court records had commenced. By 1543 this process was virtually complete, with the Tuscan dialect of Italian becoming the lingua franca of the Italian peninsula and supplanting written Sicilian.

Spanish rule had hastened this process in two important ways:

- Unlike the Aragonese, almost immediately the Spanish placed viceroys on the Sicilian throne. In a sense, the diminishing prestige of the Sicilian kingdom reflected the decline of Sicilian from an official, written language to eventually a spoken language amongst a predominantly illiterate population.

- The expulsion of all Jews from Spanish dominions that began in 1492 altered the population of Sicily. Not only did the population decline, many of whom were involved in important educated industries, but some of these Jewish families had been in Sicily for around 1,500 years, and Sicilian was their native language, which they used in their schools. Thus the seeds of a possible broad-based education system utilising books written in Sicilian were lost.

Spanish rule lasted over three centuries (not counting the Aragonese and Bourbon periods on either side) and had a significant influence on the Sicilian vocabulary. The following words are of Spanish derivation:

- arricugghìrisi – "to return home" (from recogerse; but also Catalan recollir-se)

- balanza/valanza – "scales" (from balanza)

- fileccia – "arrow" (from flecha) (cognate of Maltese vleġġa)

- làstima – "lament, annoyance" (from lástima)

- pinzeddu – "brush" (from pincel) (cognate of Maltese pinzell)

- ricivu – "receipt" (from recibo)

- spagnari – "to be frightened" (crossover of local appagnari with Spanish espantarse)

- sulità/sulitati – "solitude" (from soledad)

Since the Italian Unification (the Risorgimento of 1860–1861), the Sicilian language has been significantly influenced by (Tuscan) Italian. During the Fascist period it became obligatory that Italian be taught and spoken in all schools, whereas up to that point, Sicilian had been used extensively in schools. This process has quickened since World War II due to improving educational standards and the impact of mass media, such that increasingly, even within the family home, Sicilian is not necessarily the language of choice. The Sicilian Regional Assembly voted to make the teaching of Sicilian a part of the school curriculum at primary school level, but as of 2007 only a fraction of schools teach Sicilian. There is also little in the way of mass media offered in Sicilian. The combination of these factors means that the Sicilian language continues to adopt Italian vocabulary and grammatical forms to such an extent that many Sicilians themselves cannot distinguish between correct and incorrect Sicilian language usage.

Phonology

For the sound-to-spelling correspondence, see Sicilian orthography.| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | p b | t d | ɖ | (c) (ɟ) | k ɡ |

| Affricate | ts (dz) | tʃ dʒ | |||

| Fricative | f v | s (z) | ʃ (ʒ) | (ç) | |

| Trill | r | ||||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |

| Approximant | l | j | (w) |

| spelling | sound | example |

|---|---|---|

| ⟨a⟩ | /a/ | patri |

| ⟨e⟩ | /ɛ/ | beḍḍa |

| ⟨i⟩ | /i/ | chiḍḍu |

| ⟨o⟩ | /ɔ/ | sò |

| ⟨u⟩ | /u/ | tuttu |

Consonants

Sicilian has a number of consonant sounds that set it apart from the other major Romance languages, notably its retroflex consonants.

- ḌḌ/DD — The retroflex phoneme /ɖ/ (usually geminated or long ) is normally the result of the evolution of Latin -ll-. This sound is rare but present among Romance languages, including Sardinian, Southern Corsican, and some dialects of Calabria. Similar but not identical sounds are also found in the rest of the Extreme Southern Italian dialect group. The older sequence is retained in some dialects, while the pronunciation of this phoneme as dental is increasingly common. Traditionally in Sicilian, the sound was written as -đđ-, and in more contemporary usage -dd- has been used. It is also often found written -ddh- or -ddr- (both of which are often considered confusing, as they may also represent [dː] and , respectively). In the Cademia Siciliana orthographical proposal as well as the Vocabolario siciliano descriptive orthography, the digraph -ḍḍ- is used. For example, the counterpart to Italian bello in Sicilian is beḍḍu.

- DR and TR — The Sicilian pronunciation of the digraphs -dr- and -tr- is and , or even [ɖʐ], [ʈʂ]. If they are preceded by a nasal consonant, n is then a retroflex nasal sound [ɳ].

- GHI and CHI — The two digraphs -gh- and -ch-, when occurring before front vowel sounds i or e or a semivowel j, can be pronounced as palatal stops [ɟ] and [c]. From Italian, in place of -gl-, a geminated trigraph -ggh(i)- is used and is pronounced as [ɟː]. When -ch(j)- is geminated, -cch(j)- it can be pronounced as [cː].

- RR — The digraph -rr-, depending on the variety of Sicilian, can be a long trill [rː] (hereafter transcribed without the length mark) or a voiced retroflex sibilant [ʐː]. This innovation is also found under slightly different circumstances in Polish, where it is spelled -rz-, and in some Northern Norwegian dialects, where speakers vary between and [ɹ̝]. At the beginning of a word, the single letter r is similarly always pronounced double, though this is not indicated orthographically. This phenomenon, however, does not include words that start with a single r resulting from rhotacism or apheresis (see below), which should not be indicated orthographically to avoid confusion with regular double r.

- Voiced S and Z — The /s/ and /ts/ sounds are voiced as [z] and [dz] when after /n/ or other voiced sounds. In the Sicilian digraphs -sb- and -sv-, /s/ becomes voiced and palatalized as a voiced post-alveolar fricative [ʒ] along with the voiced sounds /b, v/.

- STR and SDR — The Sicilian trigraphs -str- and -sdr- are or [ʂː], and or [ʐː]. The t is not pronounced at all and there is a faint whistle between the s and the r, producing a similar sound to the shr of English shred, or how some English speakers pronounce "frustrated". The voiced equivalent is somewhat similar to how some English speakers might pronounce the phrase "was driving".

- Latin FL — The other unique Sicilian sound is found in those words that have been derived from Latin words containing -fl-. In standard literary Sicilian, the sound is rendered as -ci- (representing the voiceless palatal fricative /ç/), e.g. ciumi ("river", from Latin flūmen), but can also be found in written forms such as -hi-, -x(h)-, -çi-, or erroneously -sci-.

- Consonantal lenition — A further range of consonantal sound shifts occurred between the Vulgar Latin introduced to the island following Roman rule and the subsequent development of the Sicilian language. These sound shifts include: Latin -nd- to Sicilian -nn-; Latin -mb- to Sicilian -mm-; Latin -pl- to Sicilian -chi-; and Latin -li- to Sicilian -gghi-.

- Rhotacism and apheresis — This transformation is characterized by the substitution of single d by r. In Sicilian this is produced by a single flap of the tongue against the upper alveolar ridge [ɾ]. This phenomenon is known as rhotacism, that is, the substitution of r for another consonant; it is commonly found both in Eastern and Western Sicilian, and elsewhere in Southern Italy, especially in Neapolitan. It can occur internally, or it can affect initial d, in which case it should not be represented orthographically to avoid confusion with the regular r (see above). Examples : pedi ("foot") is pronounced [ˈpɛːɾi]; Madonna ("Virgin Mary") is pronounced [maˈɾɔnna]; lu diri ("to say it") is pronounced [lʊ ˈɾiːɾi]. Similarly, apheresis of some clusters may occur in certain dialects, producing instances such as 'ranni [ˈɾanni] for granni "big".

Vowels

Main article: Sicilian vowel system

Sicilian has five phonemic vowels: /i/, /ɛ/, /a/, /ɔ/, /u/. The mid-vowels /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ do not occur in unstressed position in native words but may do so in modern borrowings from Italian, English, or other languages. Historically, Sicilian /i/ and /u/ each represent the confluence of three Latin vowels (or four in unstressed position), hence their high frequency.

Unstressed /i/ and /u/ generally undergo reduction to [ɪ] and [ʊ] respectively, except in word-/phrase-final position, as in ‘possible’ and ‘rabbit’.

As in Italian, vowels are allophonically lengthened in stressed open syllables.

Omission of initial i

In the vast majority of instances in which the originating word had an initial /i/, Sicilian has dropped it completely. That has also happened when there was once an initial /e/ and, to a lesser extent, /a/ and /o/: mpurtanti "important", gnuranti "ignorant", nimicu "enemy", ntirissanti "interesting", llustrari "to illustrate", mmàggini "image", cona "icon", miricanu "American".

Gemination and contractions

In Sicilian, gemination is distinctive for most consonant phonemes, but a few can be geminated only after a vowel: /b/, /dʒ/, /ɖ/, /ɲ/, /ʃ/ and /ts/. Rarely indicated in writing, spoken Sicilian also exhibits syntactic gemination (or dubbramentu), which means that the first consonant of a word is lengthened when it is preceded by words like è, ma, e, a, di, pi, chi - meaning ‘it is, but, and, to, of, for, what’. For instance in the phrase è bonu ‘it's good’, there is a doubled /bb/ in pronunciation.

The letter ⟨j⟩ at the start of a word can have two separate sounds depending on what precedes the word. For instance, in jornu ("day"), it is pronounced [j]. However, after a nasal consonant or if it is triggered by syntactic gemination, it is pronounced [ɟ] as in un jornu with or tri jorna ("three days") with .

Another difference between the written and the spoken languages is the extent to which contractions occur in everyday speech. Thus a common expression such as avemu a accattari... ("we have to go and buy...") is generally reduced to âma 'ccattari in talking to family and friends.

The circumflex accent is commonly used in denoting a wide range of contractions in the written language, particularly the joining of simple prepositions and the definite article: di lu = dû ("of the"), a lu = ô ("to the"), pi lu = pû ("for the"), nta lu = ntô ("in the"), etc.

Grammar

Nouns and adjectives

Most feminine nouns and adjectives end in -a in the singular: casa ('house'), porta ('door'), carta ('paper'). Exceptions include soru ('sister') and ficu ('fig'). The usual masculine singular ending is -u: omu ('man'), libbru ('book'), nomu ('name'). The singular ending -i can be either masculine or feminine.

Unlike Standard Italian, Sicilian uses the same standard plural ending -i for both masculine and feminine nouns and adjectives: casi ('houses' or 'cases'), porti ('doors' or 'harbors'), tàuli ('tables'). Some masculine plural nouns end in -a instead, a feature that is derived from the Latin neuter endings -um, -a: libbra ('books'), jorna ('days'), vrazza ('arms', compare Italian braccio, braccia), jardina ('gardens'), scrittura ('writers'), signa ('signs'). Some nouns have irregular plurals: omu has òmini (compare Italian uomo, uomini), jocu ('game') jòcura (Italian gioco, giochi) and lettu ("bed") letta (Italian letto, 'letti). Three feminine nouns are invariable in the plural: manu ('hand'), ficu ('fig') and soru ('sister').

Verbs

Verb "to have"

Sicilian has only one auxiliary verb, aviri, 'to have'. It is also used to denote obligation (e.g. avi a jiri, ' has to go'), and to form the future tense, as Sicilian for the most part no longer has a synthetic future tense: avi a cantari, ' will sing'.

Verb "to go" and the periphrastic future

As in English and like most other Romance languages, Sicilian may use the verb jiri, 'to go', to signify the act of being about to do something. Vaiu a cantari, 'I'm going to sing'. In this way, jiri + a + infinitive can also be a way to form the simple future construction.

Tenses and moods

The main conjugations in Sicilian are illustrated below with the verb èssiri, 'to be'.

| Infinitive | èssiri / siri | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gerund | essennu / sennu | |||||

| Past participle | statu | |||||

| Indicative | eu/iu/ju | tu | iḍḍu | nuàutri | vuàutri | iḍḍi |

| Present | sugnu | si' | esti / è | semu | siti | sunnu / su' |

| Imperfect | era | eri | era | èramu | èravu | èranu |

| Preterite | fui | fusti | fu | fomu | fùstivu | foru |

| Future | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Conditional | ju | tu | iḍḍu | nuàutri | vuàutri | iḍḍi |

| fora | fori | fora | fòramu | fòravu | fòranu | |

| Subjunctive | ju | tu | iḍḍu | nuàutri | vuàutri | iḍḍi |

| Present | sia | si' / fussi | sia | siamu | siati | sianu |

| Imperfect | fussi | fussi | fussi | fùssimu | fùssivu | fùssiru |

| Imperative | — | tu | vossìa | — | vuàutri | — |

| — | sì | fussi | — | siti | — | |

- The synthetic future is rarely used and, as Camilleri explains, continues its decline towards complete disuse. Instead, the following methods are used to express the future:

- 1) the use of the present indicative, which is usually preceded by an adverb of time:

- Stasira vaju ô tiatru — 'This evening I go to the theatre'; or, using a similar English construction, 'This evening I am going to the theatre'

- Dumani ti scrivu — 'Tomorrow I write to you'

- 2) the use of a compound form consisting of the appropriate conjugation of aviri a ('have to') in combination with the infinitive form of the verb in question:

- Stasira aju a ghiri ('j' becomes 'gh' after a vowel) ô tiatru — 'This evening I will go to the theatre'

- Dumani t'aju a scrìviri — 'Tomorrow I will write to you'

- In speech, the contracted forms of aviri often come into play:

- aju a → hâ/hê; ai a → hâ; avi a → avâ; avemu a → amâ; aviti a → atâ

- Dumani t'hâ scrìviri — 'Tomorrow I will write to you'.

- 1) the use of the present indicative, which is usually preceded by an adverb of time:

- The synthetic conditional has also fallen into disuse (except for the dialect spoken in Messina, missinisi). The conditional has two tenses:

- 1) the present conditional, which is replaced by either:

- i) the present indicative:

- Cci chiamu si tu mi duni lu sò nùmmaru — "I call her if you give me her number', or

- ii) the imperfect subjunctive:

- Cci chiamassi si tu mi dassi lu sò nùmmaru — 'I'd call her if you would give me her number'; and

- i) the present indicative:

- 2) the past conditional, which is replaced by the pluperfect subjunctive:

- Cci avissi jutu si tu m'avissi dittu unni esti / è — 'I'd have gone if you would have told me where it is'

- In a hypothetical statement, both tenses are replaced by the imperfect and pluperfect subjunctive:

- Si fussi riccu m'accattassi nu palazzu — 'If I were rich I would buy a palace'

- S'avissi travagghiatu nun avissi patutu la misèria — 'If I had worked I would not have suffered misery'.

- 1) the present conditional, which is replaced by either:

- The second-person singular (polite) uses the older form of the present subjunctive, such as parrassi, which has the effect of softening it somewhat into a request, rather than an instruction. The second-person singular and plural forms of the imperative are identical to the present indicative, exception for the second-person singular -ari verbs, whose ending is the same as for the third-person singular: parra.

Literature

Extracts from three of Sicily's more celebrated poets are offered below to illustrate the written form of Sicilian over the last few centuries: Antonio Veneziano, Giovanni Meli and Nino Martoglio.

A translation of the Lord's Prayer can also be found in J. K. Bonner. This is written with three variations: a standard literary form from the island of Sicily and a southern Apulian literary form.

Luigi Scalia translated the biblical books of Ruth, Song of Solomon and the Gospel of Matthew into Sicilian. These were published in 1860 by Prince Louis Lucien Bonaparte.

Extract from Antonio Veneziano

Celia, Lib. 2

(c. 1575–1580)

| Sicilian | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|

| Non è xhiamma ordinaria, no, la mia, | No, la mia non è fiamma ordinaria, | No, mine is no ordinary flame, |

| è xhiamma chi sul'iu tegnu e rizettu, | è una fiamma che sol'io possiedo e controllo, | it's a flame that only I possess and control, |

| xhiamma pura e celesti, ch'ardi 'n mia; | una fiamma pura e celeste che dientro di me cresce; | a pure celestial flame that in me grows; |

| per gran misteriu e cu stupendu effettu. | da un grande mistero e con stupendo effetto. | by a great mystery and with great effect. |

| Amuri, 'ntentu a fari idulatria, | l'Amore, desiderante d'adorare icone, | Love, wanting to worship idols, |

| s'ha novamenti sazerdoti elettu; | è diventato sacerdote un'altra volta; | has once again become a high priest; |

| tu, sculpita 'ntra st'alma, sìa la dia; | tu, scolpita dentro quest'anima, sei la dea; | you, sculpted in this soul, are the goddess; |

| sacrifiziu lu cori, ara stu pettu. | il mio cuore è la vittima, il mio seno è l'altare. | my heart is the victim, my breast is the altar. |

Extract from Giovanni Meli

Don Chisciotti e Sanciu Panza (Cantu quintu)

(~1790)

| Sicilian | English |

|---|---|

| Stracanciatu di notti soli jiri; | Disguised he roams at night alone; |

| S'ammuccia ntra purtuni e cantuneri; | Hiding in any nook and cranny; |

| cu vacabunni ci mustra piaciri; | he enjoys the company of vagabonds; |

| poi lu so sbiu sunnu li sumeri, | however, donkeys are his real diversion, |

| li pruteggi e li pigghia a ben vuliri, | he protects them and looks after all their needs, |

| li tratta pri parenti e amici veri; | treating them as real family and friends; |

| siccomu ancora è n'amicu viraci | since he remains a true friend |

| di li bizzarri, capricciusi e audaci. | of all who are bizarre, capricious and bold. |

Extract from Nino Martoglio

Briscula 'n Cumpagni

(~1900; trans: A game of Briscula amongst friends)

| Sicilian | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|

| — Càrricu, mancu? Cca cc'è 'n sei di spati!... | — Nemmeno un carico? Qui c'è un sei di spade!... | — A high card perhaps? Here's the six of spades!... |

| — E chi schifiu è, di sta manera? | — Ma che schifo, in questo modo? | — What is this rubbish you're playing? |

| Don Peppi Nnappa, d'accussì jucati? | Signor Peppe Nappa, ma giocate così? | Mr. Peppe Nappa, who taught you to play this game? |

| — Massari e scecchi tutta 'a tistera, | — Messere e asino con tutti i finimenti, | — My dear gentlemen and donkeys with all your finery, |

| comu vi l'haju a diri, a vastunati, | come ve lo devo dire, forse a bastonate, | as I have repeatedly told you till I'm blue in the face, |

| ca mancu haju sali di salera! | che non ho nemmeno il sale per la saliera! | I ain't got nothing that's even worth a pinch a salt! |

Traditional prayers compared to Italian

| Patri nostru (Lord's Prayer in Sicilian) | Padre nostro (Lord's Prayer in Italian) | Aviu Maria (Hail Mary in Sicilian) | Ave Maria (Hail Mary in Italian) | Salvi o'Rigina (Salve Regina in Sicilian) | Salve Regina (in Italian) | Angelu ca ni custudisci (Angel of God in Sicilian) | Angelo Custode (Angel of God in Italian) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Influence on Italian

As one of the most spoken languages of Italy, Sicilian has notably influenced the Italian lexicon. In fact, there are several Sicilian words that are now part of the Italian language and usually refer to things closely associated to Sicilian culture, with some notable exceptions:

- arancino (from arancinu): a Sicilian cuisine specialty;

- canestrato (from ncannistratu): a cheese typical of Sicily;

- cannolo (from cannolu): a Sicilian pastry;

- cannolicchio (from cannulicchiu): razor clam;

- carnezzeria (from carnizzaria): butcher's shop;

- caruso (from carusu): boy, especially a Sicilian one;

- cassata: a Sicilian pastry;

- cirneco (from cirnecu): a small breed of dogs common in Sicily;

- cosca: a small group of criminals affiliated to the Sicilian mafia;

- curatolo (from curàtulu): watchman in a farm, with a yearly contract;

- dammuso (from dammusu): stony habitation typical of the island of Pantelleria;

- intrallazzo (from ntrallazzu): illegal exchange of goods or favours, but in a wider sense also cheat, intrigue;

- marranzano (from marranzanu): Jew's harp;

- marrobbio (from marrubbiu): quick variation of sea level produced by a store of water in the coasts as a consequence of either wind action or an atmospheric depression;

- minchia: penis in its original meaning, but also stupid person; is also widely used as interjection to show either astonishment or rage;

- picciotto (from picciottu): young man, but also the lowest grade in the Mafia hierarchy;

- pizzino (from pizzinu): small piece of paper, especially used for secret criminal communications;

- pizzo (from pizzu, literally meaning "beak", from the saying fari vagnari a pizzu "to wet one's beak"): protection money paid to the Mafia;

- quaquaraquà (onomatopoeia?; "the duck wants a say"): person devoid of value, nonentity;

- scasare (from scasari, literally "to move home"): to leave en masse;

- stidda (equivalent to Italian stella): lower Mafia organization.

Use today

Sicily

Sicilian is estimated to have 5,000,000 speakers. However, it remains very much a home language that is spoken among peers and close associates. Regional Italian has encroached on Sicilian, most evidently in the speech of the younger generations.

In terms of the written language, it is mainly restricted to poetry and theatre in Sicily. The education system does not support the language, despite recent legislative changes, as mentioned previously. Local universities either carry courses in Sicilian or describe it as dialettologia, the study of dialects.

Calabria

The dialect of Reggio Calabria is spoken by some 260,000 speakers in the Reggio Calabria metropolitan area. It is recognised, along with the other Calabrian dialects, by the regional government of Calabria by a law promulgated in 2012 that protects Calabria's linguistic heritage.

Diaspora

Outside Sicily and Southern Calabria, there is an extensive Sicilian-speaking diaspora living in several major cities across South and North America and in other parts of Europe and Australia, where Sicilian has been preserved to varying degrees.

Media

The Sicilian-American organization Arba Sicula publishes stories, poems and essays, in Sicilian with English translations, in an effort to preserve the Sicilian language, in Arba Sicula, its bi-lingual annual journal (latest issue: 2017), and in a biennial newsletter entitled Sicilia Parra.

The movie La Terra Trema (1948) is entirely in Sicilian and uses many local amateur actors.

The nonprofit organisation Cademia Siciliana publishes a Sicilian version of a quarterly magazine, "UNESCO Courier".

Sample words and phrases

| English | Sicilian |

|---|---|

| to make a good impression | fàri na beḍḍa fiùra |

| wine | vinu |

| man | masculu |

| woman | fìmmina |

| the other side | ḍḍabbanna |

| also, too | mirè |

| there | ḍḍa |

| right there | ḍḍocu |

| where | unni |

| you (formal) | vossìa |

| be careful! | accura! |

| he, him | iḍḍu |

| she, her | iḍḍa |

| once, formerly | tannu |

| he who pays before seeing the goods gets cheated (literally "who pays before, eats smelly fish") |

cu paja prima, mancia li pisci fitùsi |

See also

- Arba Sicula

- Baccagghju

- Cademia Siciliana

- Centro di studi filologici e linguistici siciliani

- Griko

- Magna Graecia

- Sicilian School

- Siculo-Arabic

- Theme of Sicily

Explanatory notes

- Peppe Nappa [it] is a character of the Commedia dell'arte, similar to Pulcinella o Arlecchino.

References

- Sicilian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Iniziative per la promozione e valorizzazione della lingua Siciliana e l'insegnamento della storia della Sicilia nelle scuole di ogni ordine e grado della Regione [Initiatives for the promotion and development of Sicilian language in the schools of all type and degree of the Region] (PDF) (resolution) (in Italian). 15 May 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ "Sicilian entry in Ethnologue". www.ethnologue.com. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

(20th ed. 2017)

- ^ Avolio, Francesco (2012). Lingue e dialetti d'Italia [Languages and dialects of Italy] (in Italian) (2nd ed.). Rome: Carocci. p. 54.

- Wei, Li; Dewaele, Jean-Marc; Housen, Alex (2002). Opportunities and Challenges of Bilingualism. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110852004.

- Facaros, Dana; Pauls, Michael (2008). Sicily. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 9781860113970.

- "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- "Lingue riconosciute dall'UNESCO e non tutelate dalla 482/99". Piacenza: Associazion Linguìstica Padaneisa. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Cipolla 2004, pp. 150–151.

- Sammartino, Peter; Roberts, William (1 January 2001). Sicily: An Informal History. Associated University Presses. ISBN 9780845348772.

- Cipolla 2004, pp. 140–141.

- Salerno, Vincenzo. "Diaspora Sicilians Outside Italy". www.bestofsicily.com. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Giacalone, Christine Guedri (2016). "Sicilian Language Usage: Language Attitudes and Usage in Sicily and Abroad". Italica. 93 (2): 305–316. ISSN 0021-3020. JSTOR 44504566.

- "Sicilian". Ethnologue. 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- Piccitto, Giorgio (1997). Vocabolario siciliano (in Italian). Centro di studi filologici e linguistici siciliani, Opera del Vocabolario siciliano.

- Cipolla, Gaetano (2013). Learn Sicilian. Legas. ISBN 978-1-881901-89-1.

- "LINGUA SICILIANA / Da Firefox in Siciliano alla proposta di Norma Ortografica, vi raccontiamo la Cademia Siciliana". Identità Insorgenti (in Italian). Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Orthography Standardisation - Cademia Siciliana". Cademia Siciliana. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "L'Accademia che studia il siciliano: "È ancora chiamato dialetto, ma ha un valore immenso"". Liveunict (in Italian). University of Catania. 6 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Standardizzazione Ortografica". Cademia Siciliana (in Italian). Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- Direttore (29 June 2024). "Google Translate in Siciliano". Il Giornale di Pantelleria (in Italian). Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- "Perché la nostra è una lingua (da tradurre): c'è Google Translate in siciliano, come si usa". Balarm.it (in Italian). Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- Cipolla 2004, pp. 163–165.

- "Centro di studi filologici e linguistici siciliani » Legge Regionale 31 maggio 2011, N. 9". www.csfls.it (in Italian). Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- "Home". www.dialektos.it (in Italian). Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Sicilian Language and Culture | LPS Course Guide". www.sas.upenn.edu. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "La langue de Pirandello bientôt enseignée". La presse de Tunisie (in French). Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Sicilian American Club". Yahoo. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013.

- Rudolph, Laura C. "Sicilian Americans - History, Modern era, The first sicilians in america". World Culture Encyclopedia.

- "Welcome to the National Sicilian American Foundation". National National Sicilian American Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Arcadipane, Michele. "Gazzetta Ufficiale della Regione Siciliana: Statuto del Comune di Caltagirone" (in Italian). Legislative and legal office of Regione Sicilia.

- Arcadipane, Michele. "Gazzetta Ufficiale della Regione Siciliana: Statuto del Comune di Grammichele" (in Italian). Legislative and legal office of Regione Sicilia.

- Cardi, Valeria (12 December 2007). "Italy moves closer to ratification of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages". Eurolang. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007.

- Legge 482. 15 December 1999.

- Bonner 2001, pp. 2–3.

- Varvaro, Alberto (1988). "Sizilien". Italienisch, Korsisch, Sardisch [Italian, Corsican, Sardinian] (in German). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

- Devoto, Giacomo; Giacomelli, Gabriella (1972). I dialetti delle regioni d'Italia [Dialects of the regions of Italy] (in Italian). Florence: Sansoni. p. 143.

- La Face, Giuseppe (2006). Il dialetto reggino – Tradizione e nuovo vocabolario [The dialect of Reggio – Tradition and new vocabulary] (in Italian). Reggio Calabria: Iiriti.

- "Et primo de siciliano examinemus ingenium: nam videtur sicilianum vulgare sibi famam pre aliis asciscere eo quod quicquid poetantur Ytali sicilianum vocatur..." Dantis Alagherii De Vulgari Eloquentia, Lib. I, XII, 2 on The Latin Library

- "Dante Online - Le Opere". www.danteonline.it.

- Privitera, Joseph Frederic (2004). Sicilian: The Oldest Romance Language. Legas. ISBN 9781881901419.

- Ruffino 2001, pp. 7–8.

- Giarrizzo 1989, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Ruffino 2001, pp. 9–11

- Ruffino 2001, p. 8.

- Albert Dauzat, Dictionnaire étymologique des noms de famille et prénoms de France, éditions Larousse, 1980, p. 41a

- Ruffino 2001, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Giarrizzo 1989

- ^ Ruffino 2001, p. 12

- "Nicu". 6 June 2022.

- 2001, p. 18. sfn error: no target: CITEREF2001 (help)

- "Guastare: significato - Dizionario italiano De Mauro". Internazionale.

- ^ Hull, Geoffrey (1989). Polyglot Italy: Languages, Dialects, Peoples. Melbourne: CIS Educational. pp. 22–25.

- Ruffino 2001, pp. 18–20.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- De Gregorio, Domenico (2 November 2007). "San Libertino di Agrigento Vescovo e martire" (in Italian). Santi e Beati. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- ^ Norwich 1992

- Trofimova, Olga; Di Legnani, Flora; Sciarrino, Chiara (2017). "I Normanni in Inghilterra e in Sicilia. Un capitolo della storia linguistica europea" (PDF) (in Italian). University of Palermo.

- "CNRTL : etymology of acheter" (in French). CNRTL.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Privitera, Joseph Frederic (2003). Sicilian. New York City: Hippocrene Books. pp. 3–4.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Cipolla 2004, p. 141

- Runciman 1958.

- Hughes 2011.

- ^ Cipolla 2004, pp. 153–155

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Ġabra". mlrs.research.um.edu.mt. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Cipolla 2004, p. 163

- La Rocca, Luigi (2000). Dizionario Siciliano Italiano (in Italian and Sicilian). Caltanissetta: Terzo Millennio. pp. 7–8.

- Bonner 2001, p. 21.

- Ruffino 2001, pp. 90–92.

- Privitera, Joseph Frederic (1998). Basic Sicilian : a brief reference grammar. Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0773483357. OCLC 39051820.

- Cipolla 2005, pp. 5–9.

- ^ Bonner 2001, pp. 11–12

- ^ "Proposta di normalizzazione ortografica comune della lingua siciliana per le varietà parlate nell'isola di Sicilia, arcipelaghi ed isole satelliti, e nell'area di Reggio Calabria di Cademia Siciliana 2017" (PDF). cademiasiciliana.org. 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Bonner, J. K. «Kirk» (2003). "Principal differences among Sicilian dialects: Part I. Phonological differences (English version)". Ianua: Revista philologica romanica: 29–38. ISSN 1616-413X.

- ^ Ledgeway, Adam; Maiden, Martin (2016). The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 479–480. ISBN 9780199677108.

- Piccitto, Giorgio (1997). Vocabolario siciliano (in Italian). Centro di studi filologici e linguistici siciliani, Opera del Vocabolario siciliano.

- ^ Piccitto 2002

- Pitrè 2002.

- Ledgeway 2016, p. 250–1.

- Camilleri 1998.

- Cipolla 2004, p. 14.

- Bonner 2001, p. 13.

- Cipolla 2005.

- Cipolla 2004, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Bonner 2001, p. 56

- Bonner 2001, p. 39.

- ^ Bonner 2001, p. 25

- Pitrè 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Camilleri 1998, p. 488

- Bonner 2001, p. 123.

- ^ Bonner 2001, p. 54–55

- Pitrè 2002, pp. 61–64.

- Camilleri 1998, p. 460.

- Bonner 2001, pp. 149–150.

- Bonner 2001, p. 45.

- Bonner 2001, p. 180.

- Arba Sicula 1980.

- Meli 1995.

- Martoglio 1993.

- Zingarelli 2006.

- "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". unesco.org.

- Ruffino 2001, pp. 108–112

- cfr art. 1 comma 2

- "Consiglio Regionale della Calabria" (PDF).

General and cited references

- Abulafia, David, The end of Muslim Sicily

- Alio, Jacqueline (2018), Sicilian Studies: A Guide and Syllabus for Educators, Trinacria, ISBN 978-1943-63918-2

- Arba Sicula (in English and Sicilian), vol. II, 1980

- Bonner, J. K. "Kirk" (2001), Introduction to Sicilian Grammar, Ottawa: Legas, ISBN 1-881901-41-6

- Camilleri, Salvatore (1998), Vocabolario Italiano Siciliano, Catania: Edizioni Greco

- Piccitto, Giorgio (2002) , Vocabolario Siciliano (in Italian and Sicilian), Catania-Palermo: Centro di Studi Filologici e Linguistici Siciliani (the orthography used in this article is substantially based on the Piccitto volumes)

- Cipolla, Gaetano (2004), "U sicilianu è na lingua o un dialettu? / Is Sicilian a Language?", Arba Sicula (in English and Sicilian), XXV (1&2)

- Cipolla, Gaetano (2005), The Sound of Sicilian: A Pronunciation Guide, Ottawa: Legas, ISBN 978-1-881901-51-8

- Giarrizzo, Salvatore (1989), Dizionario etimologico siciliano (in Italian), Palermo: Herbita

- Hughes, Robert (2011), Barcelona, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-307-76461-4

- Hull, Geoffrey (2001), Polyglot Italy: Languages, Dialects, Peoples, Ottawa: Legas, ISBN 0-949919-61-6

- Ledgeway, Adam (2016). "The dialects of Southern Italy". In Ledgeway, Adam; Maiden, Martin (eds.). The Oxford guide to the Romance languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 246–69.

- Martoglio, Nino (1993), Cipolla, Gaetano (ed.), The Poetry of Nino Martoglio (in English and Sicilian), translated by Cipolla, Gaetano, Ottawa: Legas, ISBN 1-881901-03-3

- Meli, Giovanni (1995), Moral Fables and Other Poems: A Bilingual (Sicilian/English) Anthology (in English and Sicilian), Ottawa: Legas, ISBN 978-1-881901-07-5

- Mendola, Louis (2015), Sicily's Rebellion against King Charles: The story of the Sicilian Vespers, New York City, ISBN 9781943639038

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nef, Annliese (2003) , "Géographie religieuse et continuité temporelle dans la Sicile normande (XIe-XIIe siècles): le cas des évêchés", written at Madrid, in Henriet, Patrick (ed.), À la recherche de légitimités chrétiennes – Représentations de l'espace et du temps dans l'Espagne médiévale (IXe-XIIIe siècles) (in French), Lyon

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Norwich, John Julius (1992), The Kingdom in the Sun, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 1-881901-41-6

- Pitrè, Giuseppe (2002) , Grammatica siciliana: un saggio completo del dialetto e delle parlate siciliane : in appendice approfondimenti letterari (in Italian), Brancato, ISBN 9788880315049

- Privitera, Joseph (2001), "I Nurmanni in Sicilia Pt II / The Normans in Sicily Pt II", Arba Sicula (in English and Sicilian), XXII (1&2): 148–157

- Privitera, Joseph Frederic (2004), Sicilian: The Oldest Romance Language, Ottawa: Legas, ISBN 978-1-881901-41-9

- Ruffino, Giovanni (2001), Sicilia (in Italian), Bari: Laterza, ISBN 88-421-0582-1

- Runciman, Steven (1958), The Sicilian Vespers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43774-1

- Zingarelli, Nicola (2006), Lo Zingarelli 2007. Vocabolario della lingua italiana. Con CD-ROM (in Italian), Zanichelli, ISBN 88-08-04229-4

External links

- Cademia Siciliana – a non-profit organization that promotes education, research and activism regarding the Sicilian language, as well as an orthographic standard

- Arba Sicula – a non-profit organization that promotes the language and culture of Sicily

- Napizia – Dictionary of the Sicilian Language

- Sicilian Translator

- (in Sicilian) www.linguasiciliana.org

| Languages of Sicily | |

|---|---|

| Official languages | |

| Contemporary languages | |

| Historical languages | |

| Languages of Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical linguistic minorities: Albanian, Catalan, Croatian, French, Franco-Provençal, Friulian, Germanic, Greek, Ladin, Occitan, Romani, Sardinian, Slovene, Wenzhounese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romance languages (classification) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major branches | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eastern | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Italo- Dalmatian |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reconstructed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||