For other sieges, see Siege of Smolensk (disambiguation).

| Siege of Smolensk | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Polish–Russian War (1609–1618) | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Zaporozhian Cossacks |

Tsardom of Russia Sweden | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

King Sigismund III Stanisław Żółkiewski Lew Sapieha | Mikhail Borisovich Shein | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,000 | 12,000 | ||||||

| Polish–Russian War (1609–1618) | |

|---|---|

| False Dmitry I :

|

The siege of Smolensk (Polish: oblężenie Smoleńska), also known as the Smolensk Defense in Russia (Russian: Смоленская оборона), lasted 20 months between 29 September 1609 to 13 June 1611, when the Polish army besieged the Russian city of Smolensk during the Polish–Russian War (1609–1618).

Background

In July 1608, the Commonwealth concluded a truce with Vasily Shuisky, which was to last three years and 11 months. Sigismund III Vasa, who had discreetly supported the Dmitry from the beginning, had no intention of abiding by the concluded treaty, which was evidenced by the arrival in August 1608 in the camp of the second Dmitry of a faithful supporter of the king, the starost Jan Piotr Sapieha, who was the cousin of the Grand Chancellor of Lithuania Lev Sapieha.

Russia, too, as early as the end of 1608 began to negotiate to ally with Sweden, which was at war with Poland at the time (Polish-Swedish War (1600-1611)). Eventually, Vasily Shuisky concluded an alliance treaty with Sweden in February 1609, soon after the treaty with the Swedes, he began to make territorial claims against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and assumed the provocative title of Duke of Polotsk, although Polotsk belonged to Lithuania again after the Batory wars. For Sigismund III, this became an excellent pretext to start an official war. As a result of the treaty, the Swedish army joined the Russian army.

Sigismund III Vasa, who had already decided to go to war with Russia in August 1608 and for this reason sought the support of Field Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski, who, in view of the vacancy in the position of Grand Hetman, was the supreme military commander in the Crown after the King. The king's intention was to win the tsarist crown for himself or his son Władysław, and then, after the combined forces of Russia and the Commonwealth, to regain control of his inheritance, Sweden, and to neutralise the Tartar-Turkish threat. Also important for the support of the war among the nobility, was the slogan of regaining the lands lost by Lithuania, to which the king had pledged himself in the pacta conventa. Another, propagandistic aim of the war was also to spread the Catholic religion in both conquered countries, especially important to gain support from the Pope and the Catholic monarchs of Europe. As a result, Pope Paul V declared an indulgence and jubilee for the royal victory. Zolkiewski opposed the war, as he believed that as long as the war with Sweden lasted, the state could not be involved in another conflict.

Sigismund III did not raise the issue of a future war at the Sejm of January and February 1609; however, plans for it were widely known, the nobility passed new military regulations and also legally recognised the Orthodox Church in the Commonwealth. For this reason, the outbreak of war at the beginning of 1609 was decided only by the king with the senate, with the parliamentary chamber completely ignored. A side effect of such a state of affairs was the paucity of war preparations, as, lacking the support of the Sejm, the king could only organise an army based on his own financial resources. Żółkiewski, who had hitherto been opposed to the war, did not oppose it after the decision on the war was taken at a senate council; he was only in favour of hitting Moscow, the capital of Russia, but was persuaded by the king's plans to capture Smolensk.

The King went to war from Krakow on 28 May, and met Żółkiewski on 6 June in Bełżyce near Lublin. King Sigismund III, who finally succeeded in winning Żółkiewski over to his plans, arrived in Minsk on 25 August. At that time Żółkiewski was marching through Brest Litewski and Slonim.

Sigismund III set off from Minsk and travelled through Borisov to Orsha, where Lew Sapieha was waiting for him with Lithuanian troops. Everyone in the camp was gushing with optimism, supposing that, in view of the prevailing chaos in Russia, Smolensk would not put up a stiff resistance. The Polish-Lithuanian army marched out of Orsha on 17 September. The Polish army crossed the official border with Russia after crossing the Ivara River on 21 September 1609. The Polish army, initially numbering 8500 horsemen (including 4342 hussars), grew steadily, reaching 17,000 at Smolensk. Later, the Polish-Lithuanian army was joined by a Cossack army of about 20,000 Zaporozhians.

Siege

Polish assaults

In September 1609, the Polish army under the command of King Sigismund III Vasa (22,500 men: 4,000 infantry soldiers and 8,500 cavalry with 4,342 being the Winged Hussars and later to be joined by 10,000 Zaporozhian Cossacks) approached Smolensk. The city was defended by the Russian garrison under the command of voyevoda Mikhail Borisovich Shein (over 5,400 men with 170 guns, 500 Swedes, and 14,600 inhabitants who volunteered). On 25–27 September, the invaders assaulted Smolensk for the first time with no result. Between 28 September and 4 October, the Poles were shelling the city and then decided to lay siege to it. On 19–20 July, 11 August, and 21 September, the Polish army attacked Smolensk for the second, third, and fourth time, but to no avail. The siege, the shelling, and the assaults alternated with fruitless attempts of the Polish army to persuade the citizens of Smolensk to capitulate. Negotiations in September 1610 and March 1611 did not lead anywhere.

The largest mining project at Smolensk came in December 1610; however, the Poles only managed to destroy a large portion of the outer wall, the inner walls remaining intact. The siege continued. At one point, the Polish guns breached the outer wall and the voivode of Bracław ordered his soldiers to rush in; however, the Russians could see where the breach would come and had fortified that part of the wall with more people. Both sides were slaughtered, and the Poles were eventually beaten back.

Russian demise

The citizens of Smolensk had been coping with starvation and epidemic since the summer of 1610. The weakened Russian garrison (with only about 200 remaining soldiers) was not able to repel the fifth attack of the Polish army on 3 June 1611, when after the 20 months of siege the Polish army advised by the runaway traitor Andrei Dedishin, discovered a weakness in the fortress defence and on 13 June 1611 a Cavalier of Malta, Bartłomiej Nowodworski [pl], inserted a mine into a sewer canal and the succeeding explosion created a large breach in the fortress walls. Jakub Potocki [pl] was the first on the walls. The fortress fell on the same day, with the last stage taking place after violent street fighting when some 3,000 Russians citizens blew themselves up in the Assumption Cathedral. The wounded Mikhail Shein was taken prisoner and would remain a prisoner of Poland for the next 9 years.

Gallery

-

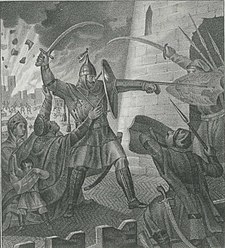

Sigismund III at Smolensk. Tommaso Dolabella.

-

The Relief of Smolensk by Polish forces during the Polish–Russian War (1609–1618).

The Relief of Smolensk by Polish forces during the Polish–Russian War (1609–1618).

-

Polish minted coin commemorating takeover of Smolensk in 1611.

-

Plaque commemorating Anniversary of 300 years since "Smolensk Defense" on the wall of Dormition Cathedral in Smolensk. It mentions Mikhail Shein, a Russian voivode.

Plaque commemorating Anniversary of 300 years since "Smolensk Defense" on the wall of Dormition Cathedral in Smolensk. It mentions Mikhail Shein, a Russian voivode.

Aftermath

Although it was a blow to lose Smolensk, it freed up Russian troops to fight the Commonwealth in Moscow, whereas Shein came to be considered a hero for holding out as long as he had. Smolensk would later become the place of a siege in 1612 and again in 1617.

See also

References

- ^ Željko., Fajfrić (2008). Ruski carevi (1. izd ed.). Sremska Mitrovica: Tabernakl. ISBN 9788685269172. OCLC 620935678.

- ^ Strizhova, I. M., ed. (2007). Veliskaya russkaya smuta : prichiny vozniknoveniya i vykhod iz gosudarstvennogo krizisa v XVI–XVII vv Великая русская смута: причины возникновения и выход из государственного кризиса в XVI-XVII вв. [The great Russian troubles: reasons for the beginning and end of the state crisis in the 16th–17th centuries]. Moscow: Dar (Даръ). ISBN 9785485001230. OCLC 230750976.