| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (August 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In algebraic topology, singular homology refers to the study of a certain set of algebraic invariants of a topological space , the so-called homology groups Intuitively, singular homology counts, for each dimension , the -dimensional holes of a space. Singular homology is a particular example of a homology theory, which has now grown to be a rather broad collection of theories. Of the various theories, it is perhaps one of the simpler ones to understand, being built on fairly concrete constructions (see also the related theory simplicial homology).

In brief, singular homology is constructed by taking maps of the standard n-simplex to a topological space, and composing them into formal sums, called singular chains. The boundary operation – mapping each -dimensional simplex to its -dimensional boundary – induces the singular chain complex. The singular homology is then the homology of the chain complex. The resulting homology groups are the same for all homotopy equivalent spaces, which is the reason for their study. These constructions can be applied to all topological spaces, and so singular homology is expressible as a functor from the category of topological spaces to the category of graded abelian groups.

Singular simplices

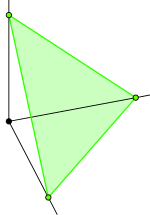

A singular n-simplex in a topological space is a continuous function (also called a map) from the standard -simplex to , written This map need not be injective, and there can be non-equivalent singular simplices with the same image in .

The boundary of denoted as is defined to be the formal sum of the singular -simplices represented by the restriction of to the faces of the standard -simplex, with an alternating sign to take orientation into account. (A formal sum is an element of the free abelian group on the simplices. The basis for the group is the infinite set of all possible singular simplices. The group operation is "addition" and the sum of simplex with simplex is usually simply designated , but and so on. Every simplex has a negative .) Thus, if we designate by its vertices

corresponding to the vertices of the standard -simplex (which of course does not fully specify the singular simplex produced by ), then

is a formal sum of the faces of the simplex image designated in a specific way. (That is, a particular face has to be the restriction of to a face of which depends on the order that its vertices are listed.) Thus, for example, the boundary of (a curve going from to ) is the formal sum (or "formal difference") .

Singular chain complex

The usual construction of singular homology proceeds by defining formal sums of simplices, which may be understood to be elements of a free abelian group, and then showing that we can define a certain group, the homology group of the topological space, involving the boundary operator.

Consider first the set of all possible singular -simplices on a topological space . This set may be used as the basis of a free abelian group, so that each singular -simplex is a generator of the group. This set of generators is of course usually infinite, frequently uncountable, as there are many ways of mapping a simplex into a typical topological space. The free abelian group generated by this basis is commonly denoted as . Elements of are called singular n-chains; they are formal sums of singular simplices with integer coefficients.

The boundary is readily extended to act on singular -chains. The extension, called the boundary operator, written as

is a homomorphism of groups. The boundary operator, together with the , form a chain complex of abelian groups, called the singular complex. It is often denoted as or more simply .

The kernel of the boundary operator is , and is called the group of singular n-cycles. The image of the boundary operator is , and is called the group of singular n-boundaries.

It can also be shown that , implying . The -th homology group of is then defined as the factor group

The elements of are called homology classes.

Homotopy invariance

If X and Y are two topological spaces with the same homotopy type (i.e. are homotopy equivalent), then

for all n ≥ 0. This means homology groups are homotopy invariants, and therefore topological invariants.

In particular, if X is a connected contractible space, then all its homology groups are 0, except .

A proof for the homotopy invariance of singular homology groups can be sketched as follows. A continuous map f: X → Y induces a homomorphism

It can be verified immediately that

i.e. f# is a chain map, which descends to homomorphisms on homology

We now show that if f and g are homotopically equivalent, then f* = g*. From this follows that if f is a homotopy equivalence, then f* is an isomorphism.

Let F : X × → Y be a homotopy that takes f to g. On the level of chains, define a homomorphism

that, geometrically speaking, takes a basis element σ: Δ → X of Cn(X) to the "prism" P(σ): Δ × I → Y. The boundary of P(σ) can be expressed as

So if α in Cn(X) is an n-cycle, then f#(α) and g#(α) differ by a boundary:

i.e. they are homologous. This proves the claim.

Homology groups of common spaces

The table below shows the k-th homology groups of n-dimensional real projective spaces RP, complex projective spaces, CP, a point, spheres S(), and a 3-torus T with integer coefficients.

| Space | Homotopy type | |

|---|---|---|

| RP | k = 0 and k = n odd | |

| k odd, 0 < k < n | ||

| 0 | otherwise | |

| CP | k = 0,2,4,...,2n | |

| 0 | otherwise | |

| point | k = 0 | |

| 0 | otherwise | |

| S | k = 0,n | |

| 0 | otherwise | |

| T | k = 0,3 | |

| k = 1,2 | ||

| 0 | otherwise | |

Functoriality

The construction above can be defined for any topological space, and is preserved by the action of continuous maps. This generality implies that singular homology theory can be recast in the language of category theory. In particular, the homology group can be understood to be a functor from the category of topological spaces Top to the category of abelian groups Ab.

Consider first that is a map from topological spaces to free abelian groups. This suggests that might be taken to be a functor, provided one can understand its action on the morphisms of Top. Now, the morphisms of Top are continuous functions, so if is a continuous map of topological spaces, it can be extended to a homomorphism of groups

by defining

where is a singular simplex, and is a singular n-chain, that is, an element of . This shows that is a functor

from the category of topological spaces to the category of abelian groups.

The boundary operator commutes with continuous maps, so that . This allows the entire chain complex to be treated as a functor. In particular, this shows that the map is a functor

from the category of topological spaces to the category of abelian groups. By the homotopy axiom, one has that is also a functor, called the homology functor, acting on hTop, the quotient homotopy category:

This distinguishes singular homology from other homology theories, wherein is still a functor, but is not necessarily defined on all of Top. In some sense, singular homology is the "largest" homology theory, in that every homology theory on a subcategory of Top agrees with singular homology on that subcategory. On the other hand, the singular homology does not have the cleanest categorical properties; such a cleanup motivates the development of other homology theories such as cellular homology.

More generally, the homology functor is defined axiomatically, as a functor on an abelian category, or, alternately, as a functor on chain complexes, satisfying axioms that require a boundary morphism that turns short exact sequences into long exact sequences. In the case of singular homology, the homology functor may be factored into two pieces, a topological piece and an algebraic piece. The topological piece is given by

which maps topological spaces as and continuous functions as . Here, then, is understood to be the singular chain functor, which maps topological spaces to the category of chain complexes Comp (or Kom). The category of chain complexes has chain complexes as its objects, and chain maps as its morphisms.

The second, algebraic part is the homology functor

which maps

and takes chain maps to maps of abelian groups. It is this homology functor that may be defined axiomatically, so that it stands on its own as a functor on the category of chain complexes.

Homotopy maps re-enter the picture by defining homotopically equivalent chain maps. Thus, one may define the quotient category hComp or K, the homotopy category of chain complexes.

Coefficients in R

Given any unital ring R, the set of singular n-simplices on a topological space can be taken to be the generators of a free R-module. That is, rather than performing the above constructions from the starting point of free abelian groups, one instead uses free R-modules in their place. All of the constructions go through with little or no change. The result of this is

which is now an R-module. Of course, it is usually not a free module. The usual homology group is regained by noting that

when one takes the ring to be the ring of integers. The notation Hn(X; R) should not be confused with the nearly identical notation Hn(X, A), which denotes the relative homology (below).

The universal coefficient theorem provides a mechanism to calculate the homology with R coefficients in terms of homology with usual integer coefficients using the short exact sequence

where Tor is the Tor functor. Of note, if R is torsion-free, then for any G, so the above short exact sequence reduces to an isomorphism between and

Relative homology

Main article: Relative homologyFor a subspace , the relative homology Hn(X, A) is understood to be the homology of the quotient of the chain complexes, that is,

where the quotient of chain complexes is given by the short exact sequence

Reduced homology

Main article: Reduced homologyThe reduced homology of a space X, annotated as is a minor modification to the usual homology which simplifies expressions of some relationships and fulfils the intuition that all homology groups of a point should be zero.

For the usual homology defined on a chain complex:

To define the reduced homology, we augment the chain complex with an additional between and zero:

where . This can be justified by interpreting the empty set as "(-1)-simplex", which means that .

The reduced homology groups are now defined by for positive n and .

For n > 0, , while for n = 0,

Cohomology

Main article: CohomologyBy dualizing the homology chain complex (i.e. applying the functor Hom(-, R), R being any ring) we obtain a cochain complex with coboundary map . The cohomology groups of X are defined as the homology groups of this complex; in a quip, "cohomology is the homology of the co ".

The cohomology groups have a richer, or at least more familiar, algebraic structure than the homology groups. Firstly, they form a differential graded algebra as follows:

- the graded set of groups form a graded R-module;

- this can be given the structure of a graded R-algebra using the cup product;

- the Bockstein homomorphism β gives a differential.

There are additional cohomology operations, and the cohomology algebra has addition structure mod p (as before, the mod p cohomology is the cohomology of the mod p cochain complex, not the mod p reduction of the cohomology), notably the Steenrod algebra structure.

Betti homology and cohomology

Since the number of homology theories has become large (see Category:Homology theory), the terms Betti homology and Betti cohomology are sometimes applied (particularly by authors writing on algebraic geometry) to the singular theory, as giving rise to the Betti numbers of the most familiar spaces such as simplicial complexes and closed manifolds.

Extraordinary homology

Main article: Extraordinary homology theoryIf one defines a homology theory axiomatically (via the Eilenberg–Steenrod axioms), and then relaxes one of the axioms (the dimension axiom), one obtains a generalized theory, called an extraordinary homology theory. These originally arose in the form of extraordinary cohomology theories, namely K-theory and cobordism theory. In this context, singular homology is referred to as ordinary homology.

See also

References

- Hatcher, 105

- Hatcher, 108

- Theorem 2.10. Hatcher, 111

- Hatcher, 144

- Hatcher, 140

- Hatcher, 110

- Hatcher, 142-143

- Hatcher, 264

- Hatcher, 115

- Hatcher, 110

- Allen Hatcher, Algebraic topology. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79160-X and ISBN 0-521-79540-0

- J.P. May, A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology, Chicago University Press ISBN 0-226-51183-9

- Joseph J. Rotman, An Introduction to Algebraic Topology, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-96678-1

, the so-called homology groups

, the so-called homology groups  Intuitively, singular homology counts, for each dimension

Intuitively, singular homology counts, for each dimension  , the

, the  -dimensional

-dimensional  from the standard

from the standard  to

to  This map need not be

This map need not be  denoted as

denoted as  is defined to be the

is defined to be the  with simplex

with simplex  is usually simply designated

is usually simply designated  , but

, but  and so on. Every simplex

and so on. Every simplex  .) Thus, if we designate

.) Thus, if we designate

of the standard

of the standard

(a curve going from

(a curve going from  to

to  ) is the formal sum (or "formal difference")

) is the formal sum (or "formal difference")  .

.

on a topological space

on a topological space  . Elements of

. Elements of  is readily extended to act on singular

is readily extended to act on singular

, form a

, form a  or more simply

or more simply  .

.

, and is called the group of singular n-cycles. The image of the boundary operator is

, and is called the group of singular n-cycles. The image of the boundary operator is  , and is called the group of singular n-boundaries.

, and is called the group of singular n-boundaries.

, implying

, implying  . The

. The

are called homology classes.

are called homology classes.

.

.

of n-dimensional real projective spaces RP, complex projective spaces, CP, a point, spheres S(

of n-dimensional real projective spaces RP, complex projective spaces, CP, a point, spheres S( ), and a 3-torus T with integer coefficients.

), and a 3-torus T with integer coefficients.

is a map from topological spaces to free abelian groups. This suggests that

is a map from topological spaces to free abelian groups. This suggests that  is a continuous map of topological spaces, it can be extended to a homomorphism of groups

is a continuous map of topological spaces, it can be extended to a homomorphism of groups

is a singular simplex, and

is a singular simplex, and  is a singular n-chain, that is, an element of

is a singular n-chain, that is, an element of

. This allows the entire chain complex to be treated as a functor. In particular, this shows that the map

. This allows the entire chain complex to be treated as a functor. In particular, this shows that the map  is a

is a

is also a functor, called the homology functor, acting on hTop, the quotient

is also a functor, called the homology functor, acting on hTop, the quotient

and continuous functions as

and continuous functions as  . Here, then,

. Here, then,  is understood to be the singular chain functor, which maps topological spaces to the

is understood to be the singular chain functor, which maps topological spaces to the

for any G, so the above short exact sequence reduces to an isomorphism between

for any G, so the above short exact sequence reduces to an isomorphism between  and

and

, the

, the

is a minor modification to the usual homology which simplifies expressions of some relationships and fulfils the intuition that all homology groups of a point should be zero.

is a minor modification to the usual homology which simplifies expressions of some relationships and fulfils the intuition that all homology groups of a point should be zero.

between

between  and zero:

and zero:

. This can be justified by interpreting the empty set as "(-1)-simplex", which means that

. This can be justified by interpreting the empty set as "(-1)-simplex", which means that  .

.

for positive n and

for positive n and  .

.

, while for n = 0,

, while for n = 0,

. The cohomology groups of X are defined as the homology groups of this complex; in a quip, "cohomology is the homology of the co ".

. The cohomology groups of X are defined as the homology groups of this complex; in a quip, "cohomology is the homology of the co ".