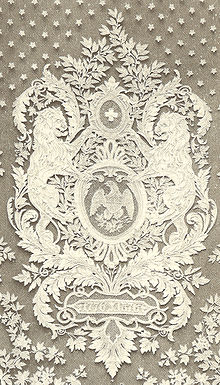

St. Gallen embroidery, sometimes known as Swiss embroidery, is embroidery from the city and the region of St. Gallen, Switzerland. The region was once the largest and most important export area for embroidery. Around 1910, its embroidery production was the largest export branch of the Swiss economy with 18 percent of the overall export value. More than 50 percent of the world production came from St. Gallen. With the advent of the First World War, the demand for the luxury dropped suddenly and significantly and so a lot of people were unemployed, which resulted in the biggest economic crisis in the region. Today, the embroidery industry has somewhat recovered, but it will probably never again reach its former size. Nevertheless, the St. Galler Spitzen (as the embroidery is also called) are still very popular as a raw material for expensive haute couture creations in Paris and count among the most famous textiles in the world.

History

Beginnings

Initial figures state that there were already up to 100,000 employees in the St. Gallen embroidery industry at the end of the 18th century, long before the invention of the hand embroidery machine. This figure is probably somewhat exaggerated, but it is an indication of the importance of embroidery in eastern Switzerland. The strengthening of the embroidery industry was accompanied by the decline of the canvas industry, especially in the city of St. Gallen itself. It had already been weakened substantially by the production of cotton started by Peter Bion, and by foreign competition. Those without livelihood in the cotton industry changed to embroidery. Later during the Continental Blockade around 1810 the cotton industry too suffered. The General-Societät der englischen Baumwollspinnerei in St. Gallen, the first Swiss stock company founded in 1801, had to close in 1817 due to lack of money.

First embroidery machines

The expansion of the embroidery industry began with the invention of the hand embroidery machine by Joshua Heilmann of Mulhouse in 1828. Just one year later, Franz Mange (1776-1846) ordered two such machines from Heilmann, under the condition that he sold no other machine in Switzerland or its immediate surroundings without Mange's consent. However, Mange allowed the Maschinen-Werkstätte und Eisengießerey, that Michael Weniger had recently opened in St. Georgen (city district of St. Gallen), the production of such machines. He himself had improved the design and several machines were exported abroad, but without lasting success for the local industry.

Mange's company passed in 1839 to his son-in-law Bartholome Rittmeyer (1786-1848), but shortly afterwards to Rittmeyer's son Franz Rittmeyer (1819-1892). Together with his mechanic and thanks to the support of Anton Saurer he improved the machinery such that the quality was now nearly equal to that of hand-embroidery. Thus, from 1852 the hand embroidery machines were manufactured in series, including at the already mentioned Maschinenfabrik in St. Georgen. Production amounted to more than 1,500 machines until 1875. The machines had the disadvantage that they were only able to do hand-like embroidery. The simultaneous invention of the sewing machine could, however, fix the problem, because now even smaller pieces could be sewn in great numbers on towels. A businessman from Hamburg called these new products Hamburghs to deceive the competitors as to the real origin of the article. Rittmeyer had to relocate and expand his factory several times because the ever-increasing demand could no longer be covered. Just by itself, the 1856-completed embroidery factory in Bruggen (later relocated to Sittertal) worked temporarily 120 machines. The sewing machine also inspired the shiffli embroidery machine which built upon the hand machine, but used a lock stitch like the sewing machine. Shiffli machines became fully automated which greatly increased productivity and thus reduced the cost of embroidery.

Rapid ascent

The meteoric rise of St. Gallen embroidery can only be explained by a combination of economic, political, and technical conditions in the second half of the 19th century. In the political environment, it was the end of the American Civil War and the onset of free trade politics; economically, inter alia, the very popular mode of the second Rococo at the French court; and in the technical conditions the development of the machines. In the years after 1860, the demand for embroidered products rose so sharply that embroidery companies sprang up like mushrooms. Many farmers, artisans, and former weavers had an embroidery machine installed in their houses for credit. Thus, embroidery had soon become in large part homework and a major addition to the income of the peasants and craftsmen, mainly in winter, as it had partially been before in the linen or spinning time. For the former, it was particularly the bad reputation of the factory and the dependence on a single employer, which let them decide for this kind of economic model; for the latter it was the capability to benefit from the possibility to increase and decrease the capacities very quickly and to let the entire economic risk remain with the workers. The embroiders also appreciated the freedom to schedule their working hours and the unlimited use of child labor, especially since the introduction of the federal factory labor law in 1877, which denied young people under 14 years of age work in factories. Particularly benefiting from the development of home embroidery were the traders, who imported the commondies for the embroiders and distributed the finished products back around the world. In the period from 1872 to 1890, the number of installed embroidery machines in the cantons of St. Gallen, Appenzell and Thurgau rose from 6,384 to 19,389, but at the same time, the number of machines installed in factories decreased from 93% to 53%. The value of goods exported to the Americas alone increased between 1867 and 1880 from 3.1 to over 21 million Swiss francs. Representatives of trading companies from overseas visited St. Gallen regularly to select patterns and to place new orders. The shipping company Danzas advertised in newspapers and praised itself as a "special agency for the embroidery traffic in St. Gallen" with postal ships to North America, East India, China, Japan, Australia and several other locations around the world. In this context we must also mention the Kaufmännische Corporation, which kept improving the framework conditions for the export trade. They built a duty-free storehouse in the city and opened a school for pattern designers; they also started today's Textile Museum.

Further developments

To the next thrust, the embroidery industry rose in 1863 with the invention of the Schifflistickmaschine by Isaak Gröbli (father of the mathematician Walter Gröbli). An experimental machine was first built in Winterthur, and later went into series production at the Adolph Saurer AG in Arbon. In 1869 a new factory with 210 of these machines opened. A temporary setback affected the embroidery industry in 1885 due to its own overproduction in a time of economic crises. Orders suddenly declined significantly, resulting in wages dropping substantially. Only around 1898 did the embroidery industry recover through various internal reforms, restrictions on maximum working hours and minimum wages, and the rise of the global economy. The last crucial step in the technical development of embroidery, the invention of the so-called automatic machines, in which the design is no longer entered using the pantographs but by punched card. The first of these machines came from Plauen. In 1911, Arnold Groebli, the son of Isaac, improved the machine at Saurer (in Arbon) so that they were in almost all respects superior to the German ones. The Schiffli- and hand embroidery machines were not removed completely, despite the now much higher speed, because the preparation of punched cards was often not worth the effort for small jobs. Since the various products of the industry had very different requirements, even in 1945, some orders were fulfilled with hand embroidery machines, or it was even embroidered entirely by hand.

The big crisis and the recovery

The decline of the embroidery industry began in 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War. The demand for luxury products–and embroidery counted among these–collapsed suddenly, and also the free trade zones were disrupted. Partially neutral countries were still customers, but they could only compensate in the short term.

To preserve wages somewhat from the free-fall, maximum working hours and minimum wages were now also fixed. In fact, these measures were rather counter-productive–only workers who demanded less than the minimum wage got a job. The year 1917, still in the middle of WWI, temporarily brought a surprising turn: the Entente forbade the export of cotton products to Germany, but not the export of embroidery. Therefore, every cloth to be sold to Germany was embroidered in some way, as embroidery could be sold. A year later, the sale of embroidery to Germany was forbidden, too, and this meant the end of the brief upturn. The last little flurry of exports came in 1919 after the end of the war, when the reconstruction of the war-stricken countries brought another short rise. With the start of the economic crisis, the heyday for the St. Gallen embroidery was finally ended. One sign of the extent of the crisis, is that from 1910 to 1930, the population of St. Gallen was reduced by emigration (as a result of unemployment) from 75,482 to 64,079.

Although embroidery exports rose again after the war, the time of the biggest economic crisis for the city began no later than the 1920s. Between 1920 and 1937, the number of embroidery machines was reduced from about 13,000 to less than 2,000. In 1929 the federal government subsidized a reduction of machines–compared with 1905, the number of people employed in industry declined by 65%. The absolute low point was reached in 1935 with an embroidery export of 640 tonnes (compared to 5,899 tons in 1913). In 1937, however, exports rose again for the first time to over 20 million Swiss francs, and the majority of the 97 newly opened facilities in the area were in the textile industry.

Working conditions

Initially, embroidery was primarily or even almost exclusively women's work, this changed abruptly with the introduction of embroidery machines. The work on the machine was now exclusively men's work, the woman was, however, still required as a helper – she took care of the replacement of broken needles and the threading, if the threads had ended (the threads in a hand-embroidery machine are only about one meter long, and it has hundreds of needless).

In traditional historiography, the above-mentioned advantages of home work were accentuated – in 1877 Dr. Wagner from the Schweizerische Gemeinnützige Gesellschaft wrote about factory work that „The greatest misery of our time is the dissolution of the family“. Today this is judged more critically. First, the earnings of homeworkers were at times very low, and secondly, many children and even grandparents had to work at the embroidery machines, in order to earn enough to survive.

While the majority of the home-workers lived in a reasonable housing with a comfortable quality of life, the workrooms were often bad, because these were in damp, poorly heated and poorly ventilated rooms (which was, for the quality of the produced textile, an advantage). The traditional historiography always emphasized the interaction between the textile industry and agriculture. The farmers, ideally would use their free time productively, have job variation, and a supplement to their poor income. Undeniably, this was actually true for a few farms. However, the competition was fierce and the loan for the machine would have to be paid back, so that often little time was left for agriculture. Also, the rough work of a farmer was not conducive for the fine embroidery work, so that many of these agricultural enterprises could only perform coarser embroidery works. Excluded from this was the pure hand embroidery by women, as it was predominantly done in Appenzell-Innerrhoden until well into the 20th century.

The earnings of the embroiderers were generally quite good, especially for the self-employed homeworkers. It was worse for the auxiliaries, who often lived from hand to mouth. The working days, notably in times of great demand, were very long. The workday lasted 10–14 hours, which caused health damage because of straining of the muscles-most embroidery machines were still operated by hand-and anemia or pulmonary tuberculosis. Moreover, the position of the embroiderers in front of the pantographs was, from an ergonomic point of view, extremely bad-the chest was severely compressed in its development and the spine was crooked. A full 25% of all embroiderers were already classified "unfit for service" at their mustering.

Also, the infant mortality in the northern, industrialized districts of the canton of St. Gallen was extraordinarily high. Various doctors tried to counteract this problem with studies and public education in the areas of health, nutrition counseling, and child care-with measurable success. Through the awareness especially of the teachers for hygiene and in the hiring of specific medics for schools, the hygiene awareness of the population improved considerably. Since 1895, the soldiers in the barracks were also supposed to shower regularly . In addition to external cleanliness the attention of the doctors also came to the "hygiene of the stomach"-the diet. Dairy and meat products were advertised as healthy and tobacco and carbohydrates came into disrepute. This benefitted the agricultural sector, which also increasingly focused on the livestock industry. Even the hitherto totally normal consumption of large amounts of alcohol was discouraged.

Embroidery today

Although embroidery no longer has the significance for the region as at the beginning of the last century, it is still an economic factor. Embroidery machine producing companies such as Benninger AG are among the larger employers in the region. Big names such as Akris, Pierre Cardin, Chanel, Christian Dior, Giorgio Armani, Emanuel Ungaro Hubert de Givenchy, Christian Lacroix, Nina Ricci, Hemant and Yves Saint Laurent work with embroidered fabrics from St. Gallen. In the city itself embroidery products are, in addition to the traditional fashion show on the CSIO and the "OFFA Frühlings- und Trendmesse St. Gallen" presented during the St. Gallen Kinderfest. This festival owes a large part of its importance and its character to the embroidery on display. The great boom of embroidery and the associated wealth of the city also has influenced its development. From today's perspective, one can say that the city was built around 1920 - apart from the later extensions at the edge of the city. The Art Nouveau and Neu-Renaissance buildings constructed from 1880 to 1930 define the image of the commercial districts built around the old city. The names of these former business places suggest the past significance of world trade for the city: Pacific, Oceanic, Atlantic, Chicago, Britannia, Washington, Florida, and so forth.

Sources

- Eric Häusler, Caspar Meili: Swiss Embroidery. Erfolg und Krise der Schweizer Stickerei-Industrie 1865-1929. Hrsg. vom Historischen Verein des Kantons St.Gallen, St. Gallen 2015, ISSN 0257-6198 PDF via: http://www.hvsg.ch/pdf/neujahrsblaetter/hvsg_neujahrsblatt_2015.pdf

- Ernst Ehrenzeller: Geschichte der Stadt St. Gallen. Hrsg. von der Walter- und -Verena-Spühl-Stiftung. VGS Verlagsgemeinschaft, St. Gallen 1988, ISBN 3-7291-1047-0

- Peter Röllin (Konzept): Stickerei-Zeit, Kultur und Kunst in St. Gallen 1870–1930. VGS Verlagsgemeinschaft, St. Gallen 1989, ISBN 3-7291-1052-7

- Max Lemmemeier: Stickereiblüte. In: Sankt-Galler Geschichte 2003, Band 6, Die Zeit des Kantons 1861–1914. Amt für Kultur des Kantons St. Gallen, St. Gallen 2003, ISBN 3-908048-43-5

References

- Battegay, Lubrich, Caspar, Naomi (2018). Jewish Switzerland: 50 Objects Tell Their Stories. Basel: Christoph Merian. pp. 118–121. ISBN 9783856168476.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)