1985 video game

| Super Mario Bros. | |

|---|---|

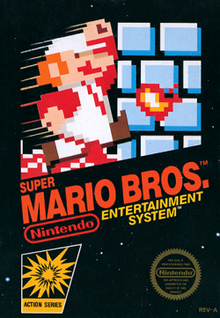

North American box art North American box art | |

| Developer(s) | Nintendo R&D4 |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| Producer(s) | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| Designer(s) |

|

| Programmer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | Koji Kondo |

| Series | Super Mario |

| Platform(s) | Nintendo Entertainment System, arcade |

| Release | NES Arcade |

| Genre(s) | Platform |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

| Arcade system | Nintendo VS. System |

Super Mario Bros. is a 1985 platform video game developed and published by Nintendo for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). It is the successor to the 1983 arcade game Mario Bros. and the first game in the Super Mario series. It was originally released in September 1985 in Japan for the Family Computer; following a US test market release for the NES, it was converted to international arcades on the Nintendo VS. System in early 1986. The NES version received a wide release in North America that year and in PAL regions in 1987.

Players control Mario, or his brother Luigi in the multiplayer mode, to traverse the Mushroom Kingdom in order to rescue Princess Toadstool from King Koopa (later named Bowser). They traverse side-scrolling stages while avoiding hazards such as enemies and pits with the aid of power-ups such as the Super Mushroom, Fire Flower, and Starman.

The game was designed by Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka as "a grand culmination" of the Famicom team's three years of game mechanics and programming, drawing from their experiences working on Devil World and the side-scrollers Excitebike and Kung Fu to advance their previous work on platforming "athletic games" such as Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. The design of the first level, World 1-1, is a tutorial for platform gameplay.

Super Mario Bros. is frequently cited as one of the greatest video games of all time, and is particularly admired for its precise controls. It has been re-released on most Nintendo systems, and is one of the best-selling games of all time, with more than 58 million copies sold worldwide. It is credited alongside the NES as one of the key factors in reviving the video game industry after the 1983 crash, and helped popularize the side-scrolling platform game genre. Koji Kondo's soundtrack is one of the earliest and most popular in video games, making music a centerpiece of game design and has since been considered one of the best video game soundtracks of all time as a result. Mario has become prominent in popular culture, and Super Mario Bros. began a multimedia franchise including a long-running game series, an animated television series, a Japanese anime feature film, a live-action feature film and an animated feature film.

Gameplay

The player controls Mario, the titular protagonist of the series. Mario's brother, Luigi, is controlled by the second player in multiplayer mode and assumes the same plot role and functionality as Mario. The objective is to quickly explore the Mushroom Kingdom, survive the main antagonist Bowser's forces, and rescue Princess Toadstool. It is a side-scrolling platform game where the player moves to the right to reach the flagpole at the end of each level.

The Mushroom Kingdom includes coins for Mario to collect and special bricks marked with a question mark (?), which when hit from below by Mario may reveal more coins or a special item. Other "secret", often invisible, bricks may contain more coins or rare items. If the player gains a Super Mushroom, Mario grows to double his size and gains the ability to break bricks above him. The item protects Mario from a single enemy or hazard. Players start with a certain number of lives and may gain extra lives by picking up green spotted 1-up mushrooms hidden in bricks, collecting 100 coins, defeating several enemies in a row with a Koopa shell, or bouncing on enemies successively without touching the ground. The player may also spawn hidden bricks with lives by collecting every coin in the previous world's third level, or by warping there. Mario loses a life if he takes damage while small, falls off the screen, or runs out of time. The game ends when the player runs out of lives, although holding the "A" button can be used on the game over screen to respawn from the first level of the world in which the player died.

Mario's primary attack is jumping onto enemies, though many enemies have differing responses to this. For example, a Goomba will flatten and be defeated, while a Koopa Troopa will temporarily retract into its shell, allowing Mario to use it as a projectile. These shells may be deflected off a wall to destroy other enemies, though they can also bounce back against Mario, which will hurt or kill him. Other enemies, such as underwater foes and enemies with spiked tops, cannot be jumped on and damage the player instead. Mario can also defeat enemies above him by jumping to hit the brick that the enemy is standing on. Mario may also acquire the Fire Flower from certain "?" blocks that when picked up changes the color of Super Mario's outfit and allows him to throw fireballs. A less common item is the Starman, which often appears when Mario hits certain concealed or otherwise invisible blocks. This item grants Mario temporary invincibility from all minor dangers.

The game consists of eight worlds, each with four sub-levels or stages. Underwater stages contain unique aquatic enemies. Bonuses and secret areas include more coins, or warp pipes that allow Mario to skip directly to later worlds. The final stage of each world is in a fiery underground castle where Bowser is fought on a suspension bridge above lava; the first seven of these Bowsers are actually minions disguised as him, and the real Bowser is in the eighth world. Bowser and his decoys are defeated by jumping over them or running under them while they are jumping and reaching the axe on the end of the bridge, or with fireballs. After completing the game once, the player is rewarded with the ability to replay with increased difficulty, such as all Goombas replaced with Buzzy Beetles, enemies similar to Koopa Troopas who cannot be defeated using the Fire Flower.

Plot

Following the events of Mario Bros., the game is set in the fantasy land of the Mushroom Kingdom after Mario and Luigi had arrived through a clay pipe from New York City.

In the Mushroom Kingdom, a tribe of turtle-like Koopa Troopas invade the kingdom and uses the magic of their king Bowser to turn the Mushroom People into inanimate objects such as bricks, stones, and horsehair plants. Bowser and his army also kidnap Princess Toadstool of the Mushroom Kingdom, the only one with the ability to reverse Bowser's spell. After hearing the news, the brothers set out to save the princess and free the kingdom from Bowser. They fight Bowser's forces while traversing the Mushroom Kingdom. After each defeat of a decoy Bowser, a Toad retainer proclaims, "Thank you Mario! But our princess is in another castle!". Finally, they reach Bowser's true stronghold, where they defeat him by throwing fireballs or by dropping him into lava, freeing the princess and saving the Mushroom Kingdom.

Development

Super Mario Bros. was designed by Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka of the Nintendo Creative Department, and largely programmed by Toshihiko Nakago of SRD, which became a longtime Nintendo partner and later a wholly owned subsidiary. The original Mario Bros., released in 1983, is an arcade platformer that takes place on a single screen with a black background. Miyamoto used the term "athletic games" to refer to what would later be known as platform games. For Super Mario Bros., Miyamoto wanted to create a more colorful "athletic game" with a scrolling screen and larger characters.

Development was a culmination of their technical knowledge from working on the 1984 games Devil World, Excitebike, and Kung Fu along with their desire to further advance the platforming "athletic game" genre they had created with their earlier games. The side-scrolling gameplay of racing game Excitebike and beat 'em up game Kung-Fu Master, the latter ported by Miyamoto's team to the NES as Kung Fu, were key steps towards Miyamoto's vision of an expansive side-scrolling platformer; in turn, Kung-Fu Master was an adaptation of the Jackie Chan film Wheels on Meals (1984). While working on Excitebike and Kung Fu, he came up with the concept of a platformer that would have the player "strategize while scrolling sideways" over long distances, have aboveground and underground levels, and have colorful backgrounds rather than black backgrounds. Super Mario Bros. used the fast scrolling game engine Miyamoto's team had originally developed for Excitebike, which allowed Mario to smoothly accelerate from a walk to a run, rather than move at a constant speed like in earlier platformers.

Miyamoto also wanted to create a game that would be the "final exclamation point" for the ROM cartridge format before the forthcoming Famicom Disk System was released. Development for Super Mario Bros. began in the fall of 1984 at the same time as The Legend of Zelda, another Famicom game directed and designed by Miyamoto and released in Japan five months later, and the games shared some elements; for instance, the fire bars that appear in the Mario castle levels began as objects in Zelda.

To have a new game available for the end-of-year shopping season, Nintendo aimed for simplicity. In December 1984, the team created a prototype in which the player moved a 16x32-pixel rectangle around a single screen. Tezuka suggested using Mario after seeing the sales figures of Mario Bros. In February 1985, the team chose the name Super Mario Bros. after implementing the Super Mushroom power-up. The game initially used a concept in which Mario or Luigi could fly a rocket ship while firing at enemies, but this went unused; the final game's sky-based bonus stages are a remnant of this concept. The team found it illogical that Mario was hurt by stomping on turtles in Mario Bros. so decided that future Mario games would "definitely have it so that you could jump on turtles all you want". Miyamoto initially imagined Bowser as an ox, inspired by the Ox King from the Toei Animation film Alakazam the Great (1960). However, Tezuka decided he looked more like a turtle, and they collaborated to create his final design.

The development of Super Mario Bros. is an early example of specialization in the video game industry, made possible and necessary by the Famicom's arcade-capable hardware. Miyamoto designed the game world and led a team of seven programmers and artists who turned his ideas into code, sprites, music, and sound effects. Developers of previous hit games joined the team in February 1985, importing many special programming techniques, features, and design refinements such as these: "Donkey Kong's slopes, lifts, conveyor belts, and ladders; Donkey Kong Jr.'s ropes, logs and springs; and Mario Bros.'s enemy attacks, enemy movement, frozen platforms and POW Blocks".

The team based the level design around a small Mario, intending to later make his size bigger in the final version, but they decided it would be fun to let Mario change his size via a power-up. The early level design was focused on teaching players that mushrooms were distinct from Goombas and would be beneficial to them, so in World 1-1, the first mushroom is difficult to avoid if it is released. The use of mushrooms to change size was influenced by Japanese folktales in which people wander into forests and eat magical mushrooms; this also resulted in the game world being named the "Mushroom Kingdom". The team had Mario begin levels as small Mario to make obtaining a mushroom more gratifying. Miyamoto explained: "When we made the prototype of the big Mario, we did not feel he was big enough. So, we came up with the idea of showing the smaller Mario first, who could be made bigger later in the game; then players could see and feel that he was bigger." Miyamoto denied rumors that developers implemented a small Mario after a bug caused only his upper half to appear. Miyamoto said the shell-kicking 1-up trick was carefully tested, but "people turned out to be a lot better at pulling the trick off for ages on end than we thought". Other features, such as blocks containing multiple coins, were inspired by programming glitches.

Super Mario Bros. was developed for a cartridge with 256 kilobits (32KiB) of program code and data and 64 kilobits (8KiB) of sprite and background graphics. Due to this storage limitation, the designers happily considered their aggressive search for space-saving opportunities to be akin to their own fun television game show competition. For instance, clouds and bushes in the game's backgrounds use that same sprite recolored, and background tiles are generated via an automatic algorithm. Around July 1985, development time was extended to 3–4 weeks to adjust and fix memory bugs. Sound effects were also recycled; the sound when Mario is damaged is the same as when he enters a pipe, and Mario jumping on an enemy is the same sound as each stroke when swimming. After completing the game, the development team decided that they should introduce players with a simple, easy-to-defeat enemy rather than beginning the game with Koopa Troopas. By this point, the project had nearly run out of memory, so the designers created the Goombas by making a single static image and flipping it back and forth to save space while creating a convincing character animation. After the addition of the game's music, around 20 bytes of open cartridge space remained. Miyamoto used this remaining space to add a sprite of a crown into the game, which would appear in the player's life counter as a reward for obtaining at least 10 lives. After filling up left-over space, the game was released to manufacturing in August 1985.

World 1-1

Main article: World 1-1During the third generation of video game consoles, tutorials on gameplay were rare. Instead, level design teaches players how a video game works. The opening section of Super Mario Bros. was therefore specifically designed in such a way that players would be forced to explore the mechanics of the game to be able to advance. Rather than confront the newly oriented player with obstacles, the first level of Super Mario Bros. lays down the variety of in-game hazards by means of repetition, iteration, and escalation. The level was finished around July 1985, when development time was furthered by 3–4 weeks to finish the rest of the game. In an interview with Eurogamer, Miyamoto explained that he created World 1-1 to contain everything a player needs to "gradually and naturally understand what they're doing", so that they can quickly understand how the game works. According to Miyamoto, once players understand the mechanics of the game, they can play more freely and it becomes "their game".

Music

See also: Super Mario Bros. themeNintendo sound designer Koji Kondo created the six-track score and all sound effects. At the time he was composing, video game music was mostly meant to attract attention, not necessarily to enhance or conform to the game. Kondo's work on Super Mario Bros. was one of the major forces in the shift towards music becoming an integral and participatory part of video games. Kondo had two specific goals for his music: "to convey an unambiguous sonic image of the game world", and "to enhance the emotional and physical experience of the gamer".

The music of Super Mario Bros. is coordinated with the onscreen animations of the various sprites, which was one way which Kondo created a sense of greater immersion. Kondo was not the first to do this in a video game, for instance, Space Invaders features a simple song that gets faster as the aliens speed up, eliciting a sense of stress and impending doom which matches the increasing challenge of the game. Unlike most games at the time, for which composers were hired later in the process to add music to a nearly finished game, Kondo was a part of the development team almost from the beginning of production, working in tandem with the rest of the team to create the game's soundtrack. Kondo's compositions were largely influenced by the game's gameplay, intending for it to "heighten the feeling" of how the game controls.

Before composition began, a prototype of the game was presented to Kondo in December 1984, so that he could get an idea of Mario's general environment and revolve the music around it. Kondo wrote the score with the help of a small piano to create appropriate melodies to fit the game's environments. After the development of the game showed progress, Kondo began to feel that his music did not quite fit the pace of the game, thus he increased the songs' tempos. The music was further adjusted based on the expectations and feedback of Nintendo's playtesters.

Kondo later composed new music for the Super Mario Bros. snow, desert, and forest level themes that appeared in the 2019 level-creator game Super Mario Maker 2.

Release

Super Mario Bros. was first released in Japan on Friday the 13th, September 13, 1985, for the Family Computer (Famicom). It was released later that year in North America for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Its exact North American release date is debated; though most sources report it was released in October 1985 as a launch game, when the NES had a limited release in the US, several sources suggest it was released between November 1985 and early 1986.

The arcade port for the Nintendo VS. System debuted in London in January 1986, and was released in other countries in February 1986. It is the first version of Super Mario Bros. to receive a wide international release, and many outside of Japan were introduced to the game through the arcade version. The NES version received a wide North American release later that year, followed by Europe on May 15, 1987.

In 1988, Super Mario Bros. was re-released along with the light gun shooting range game Duck Hunt as part of a single ROM cartridge, which came packaged with the NES as a pack-in game, as part of the console's Action Set bundle. Millions of copies of this version of the game were manufactured and sold in the United States. In 1990, another cartridge, touting those two games and World Class Track Meet, was released in North America as part of the NES Power Set bundle. It was released on May 15, 1987, in Europe, and during that year in Australia. In 1988, the game was re-released in Europe in a cartridge containing the game plus Tetris and Nintendo World Cup. The compilation was sold alone or bundled with the revised version of the NES.

Ports and re-releases

Super Mario Bros. has been ported and re-released several times. February 21, 1986, was the release of a conversion to Famicom Disk System, Nintendo's proprietary floppy disk drive.

VS. Super Mario Bros.

VS. Super Mario Bros. is a 1986 arcade adaptation of Super Mario Bros (1985), released on the Nintendo VS. System and the Nintendo VS. Unisystem (and its variant, Nintendo VS. Dualsystem). Existing levels were made much more difficult, with narrower platforms, more dangerous enemies, fewer hidden power-ups, and 200 coins needed for an extra life instead of 100. Several of the new levels went on to be featured in the Japanese sequel, Super Mario Bros. 2.

The arcade version was not officially released in Japan. Illegal coin-op versions made from a Famicom console placed inside an arcade cabinet became available in Japanese arcades by January 1986. Nintendo threatened legal action or prosecution (such as a fine or threatening a maximum sentence of up to three years in prison) against Japanese arcade operators with coin-op versions of the game. Japanese arcade operators were still able to access illegal coin-op versions through 1987.

Outside of Japan, Vs. Super Mario Bros. was officially released for arcades in overseas markets during early 1986, becoming the first version of the game to get a wide international release. The arcade game debuted at the 1986 Amusement Trades Exhibition International (ATEI) show in London, held in January 1986; this was the first appearance of Super Mario Bros. in Europe. The arcade game then received a wide international release for overseas markets outside of Japan in February 1986, initially in the form of a ROM software conversion kit. In North America, the game was featured in an official contest during the ACME convention in Chicago, held in March 1986, becoming a popular attraction at the show. It soon drew a loyal following across North American arcades, and appeared as the eighth top-grossing arcade video game on the US Play Meter arcade charts in May 1986. It went on to sell 20,000 arcade units within a few months, becoming the bestselling Nintendo VS. System release, with each unit consistently earning an average of more than $200 per week. It became the thirteenth highest-grossing arcade game of 1986 in the United States according to the annual RePlay arcade chart, which was topped by Sega's Hang-On. In Europe, it became a very popular arcade game in 1986. The arcade version introduced Super Mario Bros. to many players who did not own a Nintendo Entertainment System.

The arcade version was re-released in emulation for the Nintendo Switch by Hamster Corporation via its Arcade Archives collection on December 22, 2017. Playing that release, Chris Kohler of Kotaku called the game's intense difficulty "The meanest trick Nintendo ever played".

Super Mario Bros. Special

A remake of the game titled Super Mario Bros. Special developed by Hudson Soft was released in Japan in 1986 for the NEC PC-8801 and Sharp X1 personal computers. Though featuring similar controls and graphics, the game lacks screen scrolling due to hardware limitations, has different level designs and new items, and new enemies based on Mario Bros. and Donkey Kong.

Game and Watch

A handheld LCD game under the same name was released as a part of Nintendo's Game & Watch line of LCD games.

Modified versions

Several modified variants of the game have been released, many of which are ROM hacks of the original NES game.

On November 11, 2010, a special red variant of the Wii containing a pre-downloaded version of the game was released in Japan and Australia to celebrate its 25th anniversary. Several graphical changes include "?" blocks with the number "25" on them.

All Night Nippon Super Mario Bros., a promotional, graphically modified version of Super Mario Bros., was officially released in Japan in December 1986 for the Famicom Disk System as a promotional item given away by the popular Japanese radio show All Night Nippon. The game was published by Fuji TV, which later published Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic. The game features graphics based upon the show, with sprites of the enemies, mushroom retainers, and other characters being changed to look like famous Japanese music idols, recording artists, DJs, and other people related to All Night Nippon. The game makes use of the same slightly upgraded graphics and alternate physics featured in the Japanese release of Super Mario Bros. 2. The modern collector market considers it extremely rare, selling for nearly $500, as of 2010 (equivalent to $699 in 2023).

Speed Mario Bros. is a redux of the original Super Mario Bros. with the title changed and the gameplay speed doubled. It was released on Ultimate NES Remix on the Nintendo 3DS.

Super Luigi Bros. is a redux of the game, featured within NES Remix 2, based on a mission in NES Remix. It stars only Luigi in a mirrored version of World 1–2, scrolling from left to right, with a higher jump and a slide similar to the Japanese Super Mario Bros. 2.

Super Mario Bros. 35 was a 35-player battle royale version of the game released in 2020 that was available to play for a limited time for Nintendo Switch Online subscribers.

Remakes

Super Mario All-Stars

Main article: Super Mario All-StarsSuper Mario All-Stars, a compilation game released in 1993 for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, features a remade version of Super Mario Bros. alongside remakes of several of the other Super Mario games released for the NES. Its version of Super Mario Bros. has improved graphics and sound to match the SNES's 16-bit capabilities, and minor alterations to some of the game's collision mechanics. The player can save progress, and multiplayer mode swaps players after every level in addition to whenever a player dies. Super Mario All-Stars was also re-released for the Wii as a repackaged 25th anniversary version, featuring the same version of the game, along with a 32-page art book and a compilation CD of music from various Super Mario games.

Super Mario Bros. Deluxe

Main article: Super Mario Bros. DeluxeSuper Mario Bros. Deluxe was released on the Game Boy Color on May 10, 1999, in North America and Europe, and in 2000 in Japan exclusively to the Nintendo Power retail service. Based on the original Super Mario Bros., it features an overworld level map, simultaneous multiplayer, a Challenge mode in which the player finds hidden objects and achieves a certain score in addition to normally completing the level, and eight additional worlds based on the main worlds of the Japanese 1986 game Super Mario Bros. 2. Compared to Super Mario Bros., the game features a few minor visual upgrades such as water and lava now being animated rather than static, and a smaller screen due to the lower resolution of the Game Boy Color.

Emulation

As one of Nintendo's most popular games, Super Mario Bros. has been re-released and remade numerous times, with every single major Nintendo console up to the Nintendo Switch sporting its own port or remake of the game with the exception of the Nintendo 64.

In early 2003, Super Mario Bros. was ported to the Game Boy Advance as a part of the Famicom Minis collection in Japan and as a part of the NES Series in the US. This version of the game is emulated, identical to the original game. According to the NPD Group (which tracks game sales in North America), this became the bestselling Game Boy Advance game from June 2004 to December 2004. In 2005, Nintendo re-released this conversion as a part of the game's 20th anniversary; this special edition had approximately 876,000 units sold.

It is one of the 19 unlockable NES games included in the GameCube game Animal Crossing, for which it was distributed by Famitsu as a prize for owners of Dobutsu no Mori+; outside of this, the game cannot be unlocked through in-game conventional means, and the only way to access it is through the use of a third-party cheat device such as a GameShark or Action Replay.

Super Mario Bros. is one of the 30 games included with the NES Classic Edition, a dedicated video game console. This version allows for the use of suspension points to save in-game progress, and can be played in various different display styles, including its original 4:3 resolution, a "pixel-perfect" resolution and a style emulating the look of a cathode ray tube television.

Virtual Console

The game has been re-released for several of Nintendo's game systems as a part of their Virtual Console line of emulated classic video game releases. It was first released for the Wii on December 2, 2006, in Japan, December 25, 2006, in North America and January 5, 2007, in PAL regions. This version of the game is also one of the "trial games" made available in the "Masterpieces" section in Super Smash Bros. Brawl, where it can be demoed for a limited amount of time.

A Nintendo 3DS version was initially distributed exclusively to members of Nintendo's 3DS Ambassador Program in September 2011. A general release of the game later came through in Japan on January 5, 2012, in North America on February 16, 2012, and in Europe on March 1, 2012. The game was released for the Wii U's Virtual Console in Japan on June 5, 2013, followed by Europe on September 12, 2013, and North America on September 19, 2013.

Reception

Contemporary reception| Publication | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| Arcade | NES | |

| ACE | 955/1000 | |

| Computer and Video Games | Positive | 95% |

| The Games Machine (UK) | 89% | |

| Top Score | Positive | 4/4 |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| Amusement Players Association | Best Video Game of 1986 |

Super Mario Bros. was immensely successful, both commercially and critically. It helped popularize the side-scrolling platform game genre, and served as a killer app for the NES. Upon release in Japan, 1.2 million copies were sold during its September 1985 release month. Within four months, about 3 million copies were sold in Japan, grossing more than ¥12.2 billion, equivalent to $72 million at the time (which is inflation-adjusted to $204 million in 2023). The success of Super Mario Bros. helped increase Famicom sales to 6.2 million units by January 1986. By 1987, 5 million copies of the game had been sold for the Famicom. Outside of Japan, many were introduced to the game through the arcade version, which became the bestselling Nintendo VS. System release with 20,000 arcade units sold within a few months in early 1986. In the United States, more than 1 million copies of the NES version were sold in 1986, more than 4 million by 1988, 9.1 million by mid-1989, more than 18.7 million by early 1990, nearly 19 million by April 1990, and more than 20 million by 1991. More than 40 million copies of the original NES version had been sold worldwide by 1994, and 40.23 million by April 2000, for which it was awarded the Guinness World Record for the best-selling video game of all time.

Altogether, excluding ports and re-releases, 40.24 million copies of the original NES release have been sold worldwide, with 29 million copies sold in North America. Including ports and re-releases, more than 58 million units had been sold worldwide. The game was the all-time bestselling game for more than 20 years until its lifetime sales were ultimately surpassed by Wii Sports (2006). The game's Wii Virtual Console release was also successful, reaching number 1 by mid-2007, and at an estimated 660,000 units for $3.2 million outside of Japan and Korea in 2009. In August 2021, an anonymous buyer paid $2 million for a never-opened copy of Super Mario Bros., according to collectibles site Rally, surpassing the $1.56 million sales record set by Super Mario 64 the previous month.

Contemporary reviews

Clare Edgeley of Computer and Video Games gave the arcade version a positive review upon its ATEI 1986 debut. She felt the graphics were simple compared to other arcade games (such as Sega's Space Harrier at the same ATEI show), but was surprised at the depth of gameplay, including its length, number of hidden secrets, and the high degree of dexterity it required. She predicted that the game would be a major success. In the fall of 1986, Top Score newsletter reviewed Vs. Super Mario Bros. for arcades, calling it "without a doubt one of the best games" of the year and stating that it combined "a variety of proven play concepts" with "a number of new twists" to the gameplay. The arcade game received the award for the "Best Video Game of 1986" at the Amusement Players Association's Players Choice Awards, held during their first US national competition in January 1987 where the game was popular among arcade players.

Reviewing the NES version, the "Video Game Update" segment of Computer Entertainer magazine in June 1986 praised the "cute and comical" graphics, lively music and most of all its depth of play, including the amount of hidden surprises and discoveries. The review said it was worthy of "a spot in the hall of fame reserved for truly addictive action games" and was a "must-have" NES game. By that September, teenage videogame journalist Rawson Stovall declared in his syndicated column, " elements... develop special style that makes a must." Top Score also reviewed the NES version in early 1987, noting that it is mostly the same as the arcade version and stating that it was "a near-perfect game" with simple play mechanics, "hundreds of incentives" and hidden surprises, an "ever-changing" environment, colorful graphics and "skillfully blended" music.

The Games Machine reviewed the NES version upon its European release in 1987, calling it "a great and playable game" with praise for the gameplay, which it notes is simple to understand without needing to read the manual and has alternate routes for problems that can occasionally be frustrating but rewarding, while also praising the "splendid" graphics and sound. In 1989, ACE called it the "undisputed king of cutesy platform-style arcade adventures" and that the "game is crammed with secret levels, 'warps' and hidden treats such that you never tire of playing it". They listed it as the best NES game available in Europe. Computer and Video Games said this "platform/arcade adventure" is one of "the all-time classic video games" with "a multitude of hidden bonuses, secret warps and mystery screens." They said the graphics and sound are "good, but not outstanding, but it's the utterly addictive gameplay which makes this one of the best games money can buy".

Retrospective reception

Retrospective reception| Aggregator | Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3DS | Arcade | GBA | GBC | NES | Wii | Wii U | |

| GameRankings | 80% | 93% | 86% | ||||

| Metacritic | 84/100 | ||||||

| Publication | Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3DS | Arcade | GBA | GBC | NES | Wii | Wii U | |

| AllGame | |||||||

| GameSpot | 8.3/10 | ||||||

| IGN | 9/10 | ||||||

| Nintendo Life | |||||||

| Pocket Gamer | |||||||

Retrospective critical analysis of the game has been extremely positive, with many touting it as one of the best video games of all time. Nintendo Power named it the fourth best NES game, describing it as the beginning of the modern era of video games and "Shigeru Miyamoto's masterpiece". Electronic Gaming Monthly ranked it first on its list of the "Greatest 200 Games of Their Time". Official Nintendo Magazine also award the game first place in a 2009 list of greatest Nintendo games of all time. IGN included it in its lists of the best 100 games in 2005 and 2007. In 1997, Electronic Gaming Monthly named the All-Stars version of Super Mario Bros. the 37th best game of all time. In 2009, Game Informer named Super Mario Bros. the second greatest game of all time, behind The Legend of Zelda, saying that it "remains a monument to brilliant design and fun gameplay". The Game Informer staff also ranked it the second best in their 2001 list of the top 100 games. In 2012, G4 ranked Super Mario Bros. the best video game of all time, citing its revolutionary gameplay and its role in helping recover the North American gaming industry from the video game crash of 1983. In 2014, IGN named Super Mario Bros. the best Nintendo game, saying it was "the most important Nintendo game ever made". In 2005, IGN named it the greatest video game of all time. In 2015, The Strong National Museum of Play inducted Super Mario Bros. to its World Video Game Hall of Fame. In 2017, Polygon ranked it the eighth best Super Mario game, crediting it for starting "this franchise's habit of being an exception to so many rules". In 2018, Business Insider named it the second best Super Mario game.

Several critics have praised the game for its precise controls, which allow the player to control how high and far Mario or Luigi jumps, and how fast he runs. AllGame gave Super Mario Bros. a five-star rating, stating that "he sense of excitement, wonder and – most of all – enjoyment felt upon first playing this masterpiece of videogame can't barely be put into words. And while its sequels have far surpassed it in terms of length, graphics, sound and other aspects, Super Mario Bros., like any classic – whether of a cinematic or musical nature – has withstood the test of time, continuing to be fun and playable" and that any gamer "needs to play this game at least once, if not simply for a history lesson". Reviewing the Virtual Console Release of the game, IGN called it "an absolute must for any gamer's Virtual Console collection." Darren Calvert of Nintendo Life called the game's visuals "unavoidably outdated" compared to newer games, but mused that they were impressive at the time that the game was released.

Game Boy versions

The Game Boy Advance port of Super Mario Bros. holds an aggregate score of 84 on Metacritic. Many critics compared the port to previous ports of the game such as Super Mario Deluxe and Super Mario All-Stars, noting its seeming lack of brand new content to separate it from the original version of the game. Jeremy Parish of 1UP.com called the game "The most fun you'll ever have while being robbed blind", ultimately giving the game a score of 80% and praising its larger-scaling screen compared to Deluxe while greatly criticizing its lack of new features. IGN's Craig Harris labeled the game as a "must-have", but also mused "just don't expect much more than the original NES game repackaged on a tiny GBA cart." GameSpot gave the port a 6.8 out of 10, generally praising the gameplay but musing that the port's graphical and technical differences from the original version of the game "prevent this reissue from being as super as the original game."

The Game Boy Color port of the game also received wide critical appraisal; IGN's Craig Harris gave Super Mario Bros. Deluxe a perfect score, praising it as a perfect translation of the NES game. He hoped that it would be the example for other NES games to follow when being ported to the Game Boy Color. GameSpot gave the game a 9.9, hailing it as the "killer app" for the Game Boy Color and praising the controls and the visuals (it was also the highest rated game in the series, later surpassed by Super Mario Galaxy 2 which holds a perfect 10). Both gave it their Editors' Choice Award. Allgame's Colin Williamson praised the porting of the game and the extras, noting the only flaw of the game being that sometimes the camera goes with Mario as he jumps up. Nintendo World Report's Jon Lindemann, in 2009, called it their "(Likely) 1999 NWR Handheld Game of the Year", calling the quality of its porting and offerings undeniable. Nintendo Life gave it a perfect score, noting that it retains the qualities of the original game and the extras. St. Petersburg Times' Robb Guido commented that in this form, Super Mario Bros. "never looked better". The Lakeland Ledger's Nick S. agreed, praising the visuals and the controls. In 2004, a Game Boy Advance port of Super Mario Bros. (part of the Classic NES Series) was released, which had none of the extras or unlockables available in Super Mario Bros. Deluxe. Of that version, IGN noted that the version did not "offer nearly as much as what was already given on the Game Boy Color" and gave it an 8.0 out of 10. Super Mario Bros. Deluxe ranked third in the bestselling handheld game charts in the U.S. between June 6 and 12, 1999 with more than 2.8 million copies in the U.S. It was included on Singapore Airlines flights in 2006. Lindemann noted Deluxe as a notable handheld release in 1999.

Legacy

The success of Super Mario Bros. led to the development of many successors in the Super Mario series of video games, which in turn form the core of the greater Mario franchise. Two of these sequels, Super Mario Bros. 2 and Super Mario Bros. 3, were direct sequels to the game and were released for the NES, experiencing similar levels of commercial success. A different sequel, also titled Super Mario Bros. 2, was released for the Famicom Disk System in 1986 exclusively in Japan and was later released elsewhere under the name Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels. The gameplay concepts and elements established in Super Mario Bros. are prevalent in nearly every Super Mario game. The series consists of over 15 entries; at least one Super Mario game has been released on nearly every Nintendo console to date. Super Mario 64 is widely considered one of the greatest games ever made and is largely credited with revolutionizing the platforming genre of video games and its step from 2D to 3D. The series is one of the bestselling, with more than 310 million units sold worldwide as of September 2015. In 2010, Nintendo released special red variants of the Wii and Nintendo DSi XL consoles in re-packaged, Mario-themed limited edition bundles as part of the 25th anniversary of the game's original release. To celebrate the series' 30th anniversary, Nintendo released Super Mario Maker, a game for the Wii U which allows players to create custom platforming stages using assets from Super Mario games and in the style of Super Mario Bros. along with other styles based around different games in the series.

The game's success helped to push Mario as a worldwide cultural icon; in 1990, a study taken in North America suggested that more children in the United States were familiar with Mario than they were with Mickey Mouse, another popular media character. The game's musical score composed by Koji Kondo, particularly the game's "overworld" theme, has also become a prevalent aspect of popular culture, with the latter theme being featured in nearly every single Super Mario game. Alongside the NES platform, Super Mario Bros. is often credited for having resurrected the video game industry after the market crash of 1983. In the United States Supreme Court case Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, the Electronic Frontier Foundation submitted an amicus brief which supported overturning a law which would have banned violent video games in the state of California. The brief cited social research that declared several games, including Super Mario Bros., to contain cartoon violence similar to that of children's programs such as Mighty Mouse and Road Runner that garnered little negative reaction from the public.

Because of its status within the video game industry and being an early Nintendo game, mint condition copies of Super Mario Bros. have been considered collectors items. In 2019, the auction of a near-mint, sealed box version of the game was sold for just over $100,000, and which is considered to have drawn wider interest in the field of video game collecting. One year later in July 2020, a similar near-mint sealed box copy of the game, from the period when Nintendo was transitioning from sticker-seals to shrinkwrap, was sold for $114,000, at the time the highest price ever for a single video game.

Video game developer Yuji Naka has cited Super Mario Bros. as a large inspiration toward the concept for the immensely successful 1991 Genesis game, Sonic the Hedgehog; according to Naka, the game was conceived when he was speedrunning World 1-1 of Super Mario Bros., and considered a platformer based on moving as fast as possible.

Super Mario Bros. inspired several fangames. In 2009, developer SwingSwing released Tuper Tario Tros, a game which combines elements of Super Mario Bros. with Tetris. Super Mario Bros. Crossover, a PC fangame developed by Jay Pavlina and released in 2010 as a free browser-based game, is a full recreation of Super Mario Bros. that allows the player to alternatively control various other characters from Nintendo games, including Mega Man, Link from The Legend of Zelda, Samus Aran from Metroid, and Simon Belmont from Castlevania. Mari0, released in December 2012, combines elements of the game with that of Portal (2007) by giving Mario a portal-making gun with which to teleport through the level, and Full Screen Mario (2013) adds a level editor. In 2015, game designer Josh Millard released Ennuigi, a metafictional fangame with commentary on the original game which relates to Luigi's inability to come to terms with the game's overall lack of narrative.

Super Mario Bros. is substantial in speedrunning esports, with coverage beyond video gaming and a specific version for Guinness World Records. At the celebration of the game's 25th anniversary at the Nintendo World Store, then-record-holder andrewg attempted a speedrun as creator Miyamoto watched. In 2021, speedrunner Niftski set a historic milestone with the first run under four minutes and fifty-five seconds.

The current world record is 4.54.565 seconds, which is 533 milliseconds longer than the theoretical tool-assisted speedrun time of 4.54.032.

Minus World

Main article: Minus WorldThe Minus World (or Negative World or World Negative One) is an unbeatable glitch level present in the original NES release. World 1-2 contains a hidden warp zone, with warp pipes that transport the player to worlds 2, 3, and 4, accessed by running over a wall near the exit. If the player is able to exploit a bug that allows Mario to pass through bricks, the player can enter the warp zone by passing through the wall and the pipe to World 2-1 and 4-1 may instead transport the player to an underwater stage labeled "World -1". This stage's map is identical to worlds 2-2 and 7–2, and upon entering the warp pipe at the end, the player is taken back to the start of the level, thus trapping the player in the level until all lives have been lost. Although the level name is shown as " -1" with a leading space on the heads-up display, it is actually World 36–1, with the tile for 36 being shown as a blank space.

The Minus World bug in the Japanese Famicom Disk System version of the game behaves differently and creates multiple, completable stages. "World -1" is an underwater version of World 1–3 with an underwater level color palette and underwater level music and contains sprites of Princess Toadstool, Bowser and Hammer Bros. World -2 is an identical copy of World 7–3, and World -3 is a copy of World 4–4 with an underground level color palette and underground level music, and does not loop if the player takes the wrong path, contrary to the original World 4-4. After completing the level, Toad's usual message is displayed, but Toad himself is absent. After completing these levels, the game returns to the title screen as if completed, and is now replayable as if in a harder mode, since it is higher than world 8. There are hundreds of glitch levels beyond the Minus World (256 worlds are present including the 8 playable ones), which can be accessed in a multitude of ways, such as cheat codes or ROM hacking.

Other media

The Super Mario Bros. series has inspired various media products. In October 1985, Tokuma Shoten published the book Super Mario Bros: The Complete Strategy Guide. Its content is partly recycled from Family Computer Magazine, plus new content written by Naoto Yamamoto who received no royalties. It is Japan's bestselling book of 1985 at 630,000 copies sold. It is also Japan's bestselling book of 1986 with 860,000 copies by January 1986, and a total of 1.3 million. Nintendo of America later translated it into English as How to win at Super Mario Bros. and published it in North America via the Nintendo Fun Club and early issues of Nintendo Power magazine.

The 1986 anime film Super Mario Bros.: The Great Mission to Rescue Princess Peach! is acknowledged as one of the first feature-length films to be based directly off of a video game, and one of the earliest isekai anime. The American animated television series The Super Mario Bros. Super Show! ran from 1989 to 1990, starring professional wrestler Lou Albano as Mario and Danny Wells as Luigi. The live-action Super Mario Bros. film was released theatrically in 1993, starring Bob Hoskins as Mario and John Leguizamo as Luigi. On April 5, 2023, The Super Mario Bros. Movie, an animated feature film based on the series and created by Illumination Entertainment, was released.

Super Mario Bros. was adapted into a pinball machine by Gottlieb, released in 1992. It became one of America's top ten bestselling pinball machines of 1992, receiving a Gold Award from the American Amusement Machine Association (AAMA).

Notes

- The exact date is debated, see § Release.

- Japanese: スーパーマリオブラザーズ, Hepburn: Sūpā Mario Burazāzu

- Japanese: オールナイトニッポン スーパーマリオブラザーズ, Hepburn: Ōrunaito Nippon Sūpā Mario Burazāzu

- Japanese: スピードマリオブラザーズ, Hepburn: Supīdomarioburazāzu

- More than 50 million units of Super Mario Bros. had been sold worldwide as of 1996. 660,000 units were later sold on Wii Virtual Console, Super Mario Bros. Deluxe version sold 5.07 million units on Game Boy Color, and Classic NES Series port sold 2.27 million units on Game Boy Advance.

References

- "The history of Super Mario". Nintendo. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

Released: Oct. 18, 1985

- ^ Super Mario Bros. Instruction Booklet (PDF). USA: Nintendo of America. 1985. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- "Super Mario Bros. Hidden 1-Ups". www.stephenlindholm.com. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- Hall, Charlie (January 26, 2015). "Why didn't you tell me about this Super Mario Bros. cheat?". Polygon. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Birnbaum, Mark (March 6, 2007). "Super Mario Bros. VC review". IGN. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Geoffrey Douglas. "Super Mario Bros – Review". Allgame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- "マリオ映画公開記念!宮本茂さんインタビュー 制作の始まりから驚きの設定まで" [Commemorating the release of the Mario movie! Interview with Shigeru Miyamoto From the beginning of production to the surprising setting]. Nintendo Dream (in Japanese). April 25, 2023. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023.

もともと『マリオブラザーズ』は、土管がいっぱいあるニューヨークの地下で活躍する兄弟、ニューヨークのなかでもたぶんブルックリン、というところまで勝手に決めていて。『ドンキーコング』は舞台がニューヨークですし。その土管が不思議な森(キノコ王国)につながったのが、『スーパーマリオブラザーズ』なんです。

- Nintendo (September 13, 1985). Super Mario Bros. Nintendo. Level/area: World 8-4.

- ^ "Using the D-pad to Jump". Iwata Asks: Super Mario Bros. 25th Anniversary Vol. 5: Original Super Mario Developers. Nintendo of America. February 1, 2011. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- Ashcraft, Brian (February 24, 2022). "Nintendo Buys Longtime Partner And Super Mario Bros. Programmer SRD". Kotaku. Archived from the original on July 25, 2023. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ Gifford, Kevin. "Super Mario Bros.' 25th: Miyamoto Reveals All". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- Horowitz, Ken (July 30, 2020). Beyond Donkey Kong: A History of Nintendo Arcade Games. McFarland & Company. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-4766-4176-8. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Dingman, Shane (September 11, 2015). "Thirty things to love about Mario as Nintendo's star turns 30". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- Shigeru Miyamoto (December 2010). Super Mario Bros. 25th Anniversary - Interview with Shigeru Miyamoto #2 (in Japanese). Nintendo Channel. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Williams, Andrew (March 16, 2017). History of Digital Games: Developments in Art, Design and Interaction. CRC Press. pp. 152–4. ISBN 978-1-317-50381-1.

- ^ Iwata, Satoru (2009). "Iwata Asks: New Super Mario Bros (Volume 2- It Started With a Square Object Moving)". Archived from the original on December 15, 2009. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Birch, Nathan (April 24, 2014). "20 Fascinating Facts You Might Not Know about 'Super Mario Bros.'". Uproxx. Archived from the original on March 16, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ "Keeping It Simple". Iwata Asks: Super Mario Bros. 25th Anniversary. Nintendo. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved October 25, 2010.

- ^ Satoru Iwata (September 13, 2010). "Iwata Asks: Super Mario 25th Anniversary, Vol. 5, Page 1". Nintendo. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ "Super Mario Bros. and Super Mario Bros. 3 developer interviews- NES Classic Edition". Nintendo.com. Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- Gantayat, Anoop (October 25, 2010). "Super Mario Bros. Originally Had Beam Guns and Rocket Packs". Andriasang. Archived from the original on January 26, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- Miggels, Brian; Claiborn, Samuel. "The Mario You Never Knew". IGN. Archived from the original on December 25, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- "Iwata Asks Volume 8- Flipnote Studios-An Animation Class 4.My First Project: Draw a Rug". Nintendo of Europe. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012.2009-08-11

- O'Donnell, Casey (2012). "This Is Not A Software Industry". In Zackariasson, Peter; Wilson, Timothy L. (eds.). The Video Game Industry: Formation, Present State, and Future. Routledge.

- ^ "Iwata Asks- Super Mario Bros. 25th Anniversary (3. The Grand Culmination)". Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Satoru Iwata (September 13, 2010). "Iwata Asks: Super Mario 25th Anniversary, Vol. 5, Page 4". Nintendo. Archived from the original on February 24, 2023. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- "Letting Everyone Know It Was A Good Mushroom". Iwata Asks: New Super Mario Bros Wii. Nintendo. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ DeMaria, Rusel; Wilson, Johnny L. (2004). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games. Emeryville, California: McGraw-Hill/Osborne. pp. 238–240. ISBN 0-07-223172-6.

- Altice, Nathan (September 11, 2015). "The long shadow of Super Mario Bros". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ Shigeru Miyamoto (December 7, 2010). Super Mario Bros. 25th Anniversary - Interview with Shigeru Miyamoto #1. Nintendo. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- "Iwata Asks- New Super Mario Bros. Wii (Volume 6: Applying A Single Idea To Both Land And Sky)". Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- VG Docs (September 13, 2020). The Development History of Super Mario Bros.: 35th Anniversary (Documentary/Retrospective). YouTube. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- Parish, Jeremy (2012). "Learning Through Level Design with Mario". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- Robinson, Martin (September 7, 2015). "Video: Miyamoto on how Nintendo made Mario's most iconic level". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 21, 2016.

- Kerr, Chris (September 8, 2015). "How Miyamoto built Super Mario Bros.' legendary World 1-1". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- "Behind the Mario Maestro's Music". Wired News. March 15, 2007. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ^ Schartmann, Andrew (2015). Koji Kondo's Super Mario Bros. Soundtrack. New York: Bloomsbury. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-62892-853-2.

- Schartmann, Andrew (2015). Koji Kondo's Super Mario Bros. Soundtrack. New York: Bloomsbury. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-62892-853-2.

- Laroche, G. (2012). Analyzing musical Mario-media: Variations in the music of Super Mario video games (Thesis). McGill University Libraries. ISBN 978-0-494-84768-8. ProQuest 1251652155. (Order No. MR84768).

- Schartmann, Andrew (2015). Koji Kondo's Super Mario Bros. Soundtrack. New York: Bloomsbury. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-62892-853-2.

- "Super Mario Bros. Composer Koji Kondo Interview". 1up.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- "Super Mario Bros. Video Game, Japanese Soundtrack Illustration". GameTrailers. Archived from the original on May 30, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- Video on YouTube

- ^ DeMaria, Rusel (December 7, 2018). High Score! Expanded: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games 3rd Edition. CRC Press. p. 1611. ISBN 978-0-429-77139-2. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

13 September 1985: Friday the 13th, a traditionally unlucky day in America but not in Japan. Nintendo releases Super Mario Bros. for the Famicom. It sells 1,200,000 copies by the end of the month.

- ^ Cifaldi, Frank (March 28, 2012). "Sad But True: We Can't Prove When Super Mario Bros. Came Out". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- "Macy's advertisement". New York Times. November 17, 1985. p. A29.

- ^ Edgeley, Clare (February 16, 1986). "Arcade Action: Arcade Show '86". Computer and Video Games. No. 53 (March 1986). United Kingdom: EMAP. pp. 82–83 (83). Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ "News". Play Meter. Vol. 12, no. 1. January 15, 1986. pp. 7, 28.

- ^ Akagi, Masumi (October 13, 2006). アーケードTVゲームリスト国内•海外編(1971-2005) [Arcade TV Game List: Domestic • Overseas Edition (1971-2005)] (in Japanese). Japan: Amusement News Agency. p. 57. ISBN 978-4990251215.

- ^ "Two Pick-Hits for the Nintendo Entertainment System". Top Score. Amusement Players Association. Winter 1987.

- ^ Horowitz, Ken (July 30, 2020). Beyond Donkey Kong: A History of Nintendo Arcade Games. McFarland & Company. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-4766-4176-8. Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- "111.4908: Super Mario Bros. / Duck Hunt". museumofplay.org. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Birch, Nathan (October 3, 2014). "How To Shoot The Dog And Other Facts You Probably Don't Know About 'Duck Hunt'". Uproxx. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Tognotti, Chris (July 30, 2017). "Vintage, still-wrapped Super Mario Bros. NES cartridge sells for $30,000". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- "108.5270: Super Mario Bros. / Duck Hunt / World Class Track Meet". museumofplay.org. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Duck Hunt/Super Mario Bros. instruction booklet. USA: Nintendo. 1988. NES-MH-USA.

- Whitehead, Thomas (September 17, 2015). "Decade-Old Japanese Shigeru Miyamoto Interview Shows How Super Mario Bros. Helped Save the NES". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ Orland, Kyle (September 14, 2015). "30 years, 30 memorable facts about Super Mario Bros". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ "Overseas Readers Column: "Super Mario Bros." Boom Bringing Best Selling Book" (PDF). Game Machine. No. 275. Amusement Press, Inc. January 15, 1986. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ "Overseas ReadersColumn: Jaleco Ships New Game For "VS. System"" (PDF). Game Machine. No. 282. Amusement Press, Inc. May 1, 1986. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- "Namco's "Family Stadium" Has Enjoyed Popularity (Paragraphs 9-11)" (PDF). Game Machine. Amusement Press. June 15, 1987. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Nintendo Names 'Ca$h Grab' Winners" (PDF). Cash Box. Vol. 49, no. 44. United States. April 19, 1986. p. 37. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- "National Play Meter". Play Meter. Vol. 12, no. 12. July 15, 1986. pp. 74–5.

- "Gaming Gossip..." Top Score. Amusement Players Association. Fall 1986.

- "Top 20 of 1986". Top Score. Amusement Players Association. July–August 1987. p. 3. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- Edgeley, Clare (December 16, 1986). "Arcade Action". Computer and Video Games. No. 63 (January 1987). United Kingdom: EMAP. pp. 138–9. ISSN 0261-3697.

- "Arcade Archives VS. SUPER MARIO BROS". Nintendo.co.uk. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- Whitehead, Thomas (November 17, 2017). "VS. Super Mario Bros. Arcade Archives Release Set for Festive Arrival on Switch". Nintendo Life. Nlife Media. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- Kohler, Chris (December 22, 2017). "Vs. Super Mario Bros. Is The Meanest Trick Nintendo Ever Played". Kotaku. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- "107.1265: Super Mario Bros. Game & Watch". Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (October 7, 2010). "Nintendo Hacks Super Mario Bros. for Limited-Edition Wii". Wired. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- Nicholson, James (October 27, 2010). "AU: Mario's 25th Anniversary Wii Bundles!". IGN. Archived from the original on January 19, 2023.

- Fletcher, JC (July 15, 2016). "Virtually Overlooked: All Night Nippon Super Mario Bros". Engadget. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- "Ultimate NES Remix includes Famicom Remix, Speed Mario Bros. modes". Engadget. July 15, 2016. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- Wilson, Jason (April 10, 2014). "NES Remix 2's Super Luigi Bros. is a speedrunner's ass-backward nightmare". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on April 22, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- "Little Mac Joins Super Smash Bros., Mario Kart 8 Launching May 30 with Koopalings & More". ComingSoon.net. February 14, 2014. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- "SNES: Super Mario All-Stars". GameSpot. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Kuchera, Ben (October 28, 2010). "Nintendo bringing classic Mario games to the Wii for $30". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on March 2, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- "Super Mario Bros". Game List. Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on April 27, 1999. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- "Game Boy Color: Super Mario Bros. Deluxe". GameSpot. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Mason, Graeme (July 27, 2016). "The best Game Boy games of all time". gamesradar.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Thorsen, Tor (November 21, 2005). "ChartSpot: June 2004". GameSpot. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Davidson, Joey (August 21, 2016). "Animal Crossing on Gamecube let you play full NES games for free, and it was amazing". Techno Buffalo. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- Sao, Akinori. "Super Mario Bros. Developer Interview - NES Classic Edition". Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ Gerstmann, Jeff (January 2, 2007). "Super Mario Bros. Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 31, 2011. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- Birnbaum, Mark (March 6, 2007). "Super Mario Bros. VC Review". IGN. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- "Masterpieces". Smash Bros. DOJO!!. Archived from the original on January 28, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- "Super Mario Bros. (NES) News, Reviews, Trailer & Screenshots". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ "Console Wars" (PDF). ACE. No. 26 (November 1989). October 1989. p. 144. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "Complete Games Guide" (PDF). Computer and Video Games. No. Complete Guide to Consoles. October 16, 1989. pp. 46–77. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ "Making Turtle Soup: Super Mario Bros". The Games Machine. No. 2 (December 1987 - January 1988). November 19, 1987. p. 148. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ "Strategy Session: How to Master Vs. Super Mario Bros". Top Score. Amusement Players Association. Fall 1986.

- ^ "Amusement Players Association's Players Choice Awards". Top Score. Amusement Players Association. Winter 1987.

- Minotti, Mike (September 13, 2015). "Super Mario Bros. is 30 years old today and deserves our thanks". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ Davs, Cameron (January 28, 2000). "Super Mario Bros. Deluxe for Game Boy Color Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- "The Yoke". The Yoke. No. 9–25. Yokohama Association for International Communications and Exchanges. 1985. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

"Super Mario Brothers" is one of the family computer games which is enjoying huge popularity among the children of Japan. More than three million of these games have been sold.

- "Where every home game turns out to be a winner". The Guardian. March 6, 1986. p. 15. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

Games cost 4,900 yen each (£19) but are discounted to 3,800 yen (£14.50) in Akihabara and similar shopping areas. Nintendo offers 31 cartridges, with the most popular — Super Mario Bros — selling over three million.

- "Japan Quarterly". Japan Quarterly. Asahi Shinbun. 1986. p. 296. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2021 – via Google Books.

Nevertheless, Nintendo can claim among its successes Japan's current game best seller, Super Mario Brothers. Introduced in September 1985, sales of the ¥4,900 game soared to 2.5 million copies in just four months, generating revenues of more than ¥12.2 billion (about $72 million).

- "Overseas Readers Column: Coin-Op "Super Mario" Will Ship To Overseas" (PDF). Game Machine. No. 278. Amusement Press, Inc. March 1, 1986. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- "Business Week". Business Week. No. 3024–32. Bloomberg L.P. 1987. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

Nintendo's huge fami-com owner base, where a megahit like Super Mario Bros. can sell 5 million copies.

- DeMaria, Rusel; Meston, Zach (1991). Super Mario World Game Secrets. Prima Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-55958-156-1. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

Super Mario Bros. featured Mario in a romp through eight delightfully varied worlds, each one jam-packed with action and adventure. The game sold more than one million copies in 1986 alone. (Today, Super Mario Bros. comes packaged with the NES.)

- Belson, Eve (December 1988). "A Chip off the Old Silicon Block". Orange Coast Magazine. Vol. 14, no. 12. Emmis Communications. pp. 87–90. ISSN 0279-0483 – via Google Books.

- "The rise and rise of Nintendo" (PDF). New Computer Express. No. 39 (August 5, 1989). August 3, 1989. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- Dretzka, Gary (March 29, 1990). "U.S. Parents! Get Ready For The 3rd Invasion Of Super Mario Bros". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 18, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- Rothstein, Edward (April 26, 1990). "Electronics Notebook; Adventures in Never-Never Land". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 9, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2021.

- Rich, Jason (1991). A Parent's Guide to Video Games: A Practical Guide to Selecting and Managing Home Video Games. DMS. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-9625057-7-5. Archived from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

U.S. version of SUPER MARIO BROTHERS, which has sold over 20 million copies.

- Schnaars, Steven P. (September 30, 1994). Managing Imitation Strategies. Free Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-02-928105-5. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

In 1986, its first year of sales, Nintendo sold 1.1 million NES units, largely on the strength of Super Mario Brothers, a game that eventually sold 40 million copies.

- "Computer Games: Best-Selling Computer Games". Guinness World Records 2001. Guinness. 2000. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-85112-102-4.

- Fox, Glen (July 29, 2018). "Guide: The Best Mario Games - Every Super Mario Game Ranked". Nintendo Life. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- Stewart, Keith (September 13, 2010). "Super Mario Bros: 25 Mario facts for the 25th anniversary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- "25 crazy facts about mario that change everything". MTV. Archived from the original on March 16, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "The History of Mario: A look in Mario's roots may help gamers see Nintendo's famous mascot within a bigger framework". IGN. September 30, 1996. Archived from the original on March 11, 2002. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

Nintendo's first U.S. home videogame console, the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was released in 1985 with Mario starring in Super Mario Bros. The legendary title has gone on to sell more than 50 million units worldwide.

- ^ Hatfield, Daemon (February 23, 2010). "WiiWare, Virtual Console Sales Exposed". IGN. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- 2004 CESAゲーム白書 (2004 CESA Games White Paper). Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association. July 2004. pp. 58–63. ISBN 4-902346-04-4.

- "Getting That "Resort Feel"". Iwata Asks: Wii Sports Resort. Nintendo. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016.

As it comes free with every Wii console outside Japan, I'm not quite sure if calling it "World Number One" is exactly the right way to describe it, but in any case it's surpassed the record set by Super Mario Bros., which was unbroken for over twenty years.

- Kuchera, Ben (June 1, 2007). "Nintendo announces 4.7 million Virtual Console games sold, Mario rules the top five list". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- Browning, Kellen (August 6, 2021). "A Super Mario Bros. game sells for $2 million, another record for gaming collectibles". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- "The Video Game Update: Super Mario Bros" (PDF). Computer Entertainer. Vol. 5, no. 3. June 1986. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- Hamilton, Kirk (January 30, 2014). "The First and Only English-Language Review of Super Mario Bros". Kotaku. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- Stovall, Rawson (September 12, 1986). "Adventure has met its match". Video Beat. Abilene Reporter-News. p. 2D. Archived from the original on May 30, 2024. Retrieved May 30, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Super Mario Bros. for NES". GameRankings. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- "Classic NES Series: Super Mario Bros. for Game Boy Advance". GameRankings. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- "Super Mario Bros. Deluxe for Game Boy Color". GameRankings. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ "Classic NES Series: Super Mario Bros. Critic Reviews for Game Boy Advance". Metacritic. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- "Super Mario Bros. [PlayChoice] - Overview (Arcade)". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- "Super Mario Bros. [Virtual Console] - Overview (Nintendo 3DS)". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- "Super Mario Bros. [Classic NES Series] - Overview (Game Boy Advance)". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- "Super Mario Bros. [Virtual Console] - Overview (Wii)". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- "Super Mario Bros. [Virtual Console] - Overview (Wii U)". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- Gerstmann, Jeff. "Super Mario Bros Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 26, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- Birnbaum, Mark (March 6, 2007). "Super Mario Bros. VC Review". IGN. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- Reed, Philip J. (September 13, 2013). "Review: Super Mario Bros. (Wii U eShop / NES)". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- Willington, Peter (May 9, 2012). "Super Mario Bros". Pocket Gamer. Archived from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- Sources calling Super Mario Bros. one of the all-time best games include these:

- "G4TV's Top 100 Games". www.g4tv.com. G4. 2012. Archived from the original on November 23, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- "Top 100 Greatest Video Games Ever Made". www.gamingbolt.com. GamingBolt. April 19, 2013. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "The Top 200 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 200. January 2010.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games of All Time". IGN. 2003. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games of All Time". IGN. 2005. Archived from the original on May 17, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2024.

- "The Top 100 Games of All Time!". IGN. 2007. Archived from the original on December 3, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "Top 100 Games Of All Time". IGN. 2015. Archived from the original on May 26, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". slantmagazine.com. June 9, 2014. Archived from the original on July 12, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "All-TIME 100 Video Games". Time. November 15, 2012. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- Peckham, Matt; Eadicicco, Lisa; Fitzpatrick, Alex; Vella, Matt; Patrick Pullen, John; Raab, Josh; Grossman, Lev (August 23, 2016). "The 50 Best Video Games of All Time". Archived from the original on August 30, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- Polygon Staff (November 27, 2017). "The 500 Best Video Games of All Time". Polygon.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- "The Top 300 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 300. April 2018.

- "Nintendo Power – The 20th Anniversary Issue!". Nintendo Power. Vol. 231, no. 231. San Francisco, California: Future US. August 2008. p. 71.

- "The Greatest 200 Videogames of Their Time". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- East, Tom. "100 Best Nintendo Games – Part Six". Official Nintendo Magazine. Future plc. Archived from the original on February 20, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games". IGN. 2005. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- "100 Best Games of All Time". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 100. Ziff Davis. November 1997. pp. 134, 136. Note: Contrary to the title, the intro to the article explicitly states that the list covers console video games only, meaning PC games and arcade games were not eligible.

- Staff (December 2009). "The Top 200 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 200. pp. 44–79. ISSN 1067-6392. OCLC 27315596.

- Cork, Jeff (November 16, 2009). "Game Informer's Top 100 Games of All Time (Circa Issue 100)". Game Informer. Archived from the original on February 19, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- "G4TV's Top 100 Games – 1 Super Mario Bros". G4TV. 2012. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- "The Top 125 Nintendo Games of All Time". IGN. September 24, 2014. Archived from the original on March 24, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "IGN's Top 100 Games". ign.com. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- "Super Mario Bros". The Strong National Museum of Play. The Strong. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- Parish, Jeremy (November 8, 2017). "Ranking the core Super Mario games". Polygon. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- "RANKED: The 10 best Super Mario games of all time". businessinsider.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- Calvert, Darren (December 26, 2006). "Super Mario Bros. Review - NES". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- Parish, Jeremy (March 29, 2004). "Super Mario Bros. (Famicom Mini 01) (GBA)". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2004. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- Harris, Craig (June 4, 2004). "Classic NES Series: Super Mario Bros". IGN. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- Gerstmann, Jeff (June 8, 2004). "Classic NES Series: Super Mario Bros. Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Harris, Craig (July 21, 1999). "IGN: Super Mario Bros. Deluxe Review". IGN.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2007. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- "IGN Editors' Choice Games". IGN. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- "Super Mario Bros. Deluxe for GBC – Super Mario Bros. Deluxe Game Boy Color – Super Mario Bros. Deluxe GBC Game". GameSpot. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- Williamson, Colin (October 3, 2010). "Super Mario Bros. Deluxe – Review". Allgame. Archived from the original on February 16, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- "Feature – 1999 NWR Handheld Game of the Year". Nintendo World Report. March 7, 2009. Archived from the original on January 21, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- "Super Mario Bros. Deluxe (Retro) review". Retro.nintendolife.com. March 29, 2010. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- Guido, Robb (June 14, 1999). "Games heat up for the summer Series: TECH TIMES; SUMMER tech guide for kids; games". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2010.