| This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (September 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Tom King's Coffee House (later known as Moll King's Coffee House) was a notorious establishment in Covent Garden, London in the mid-18th century. Open from the time the taverns shut until dawn, it was ostensibly a coffee house, but in reality served as a meeting place for prostitutes and their customers. By refusing to provide beds, the Kings ensured that they never risked charges of brothel-keeping, but the venue was nevertheless a rowdy drinking den and a favourite target for the moral reformers of the day.

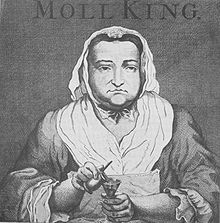

Tom and Moll King

Tom King was born in 1694 to Thomas King, a squire from Thurlow, Essex, and Elizabeth Cordell, the daughter of Baronet Sir John Cordell. He was educated at Eton and King's College, Cambridge but was expelled (for reasons unknown) and eventually drifted to Covent Garden where he worked as a handyman, and met Moll (real name Elizabeth Adkins) in 1717.

Moll had been born in Vine Street in the slum district of St Giles in 1696; her father was a cobbler and her mother a fruit and vegetable seller in Covent Garden. She had gone into service at the age of fourteen, but found the work boring and so began hawking fruit and nuts around the Covent Garden area. Tom and Moll were married in 1717, but did not live together long. Tom began an affair, neglecting Moll, and when he eventually started to beat her, she left him and took up with a man named Murray (sometimes identified as William Murray, later Earl of Mansfield and Lord Chief Justice: this identification is erroneous, as William Murray was aged only 13 in 1718). However, Tom amassed some money from working as a waiter, and, around 1720, he and Moll reunited and opened a coffee house in one of the shacks in Covent Garden which they rented from the Duke of Bedford at the cost of £12 a year.

Coffee house

The coffee house was an immediate success. Moll, who had been befriended by many of the leading courtesans of day while running her stall, made connections with fashionable society during her dalliance with Murray, and Tom had aristocratic connections of his own. The patronage of these groups, coupled with hard work and a policy of remaining open all night, meant that Tom and Moll were soon able to afford to rent out a second and third shack. A pretty black barmaid named Black Betty (also known as Tawny Betty) provided another attraction. The shacks can be seen in many of the contemporary depictions of the piazza and features prominently in William Hogarth's Four Times of the Day (although it is rotated from its true position for the artistic effect of contrasting it with Inigo Jones' Church of St Paul).

By 1722, Tom King's Coffee House was already famed as a place where anybody from the highest to the lowest could find a willing partner, and was frequented by many notables of the day: "all gentlemen to whom beds were unknown". Hogarth, Alexander Pope, John Gay, and Henry Fielding were all visitors. Fielding mentions it in both The Covent-Garden Tragedy and Pasquin and Tobias Smollett in The Adventures of Roderick Random. Of the three shacks, the largest and most famous was known as the Long Room, while the two smaller ones were reserved for gambling and drinking, respectively.

Despite the role of the coffee house as a meeting place for whores and their clients, Moll insisted that there be no beds in any of the shacks other than the bed she and Tom shared (which was in the roof and accessible only by a ladder which they pulled up behind themselves). This avoided the danger of prosecution for brothel-keeping, which could result in a whipping and a term in prison. The proximity of many well-known brothels made the provision of beds unnecessary anyway; customers were encouraged to stay until they were too drunk to go home, at which point they would be escorted to one of the nearby bagnios. Nevertheless, many of the moral campaigners of the time were keen to shut down the establishment. Sir John Gonson, a fervent supporter of the Society for the Reformation of Manners and renowned raider of brothels, regularly sent informers to the coffee house to try and uncover some offence. To counter this, Tom, Moll and their cronies developed their own secret language, Talking Flash, to render their discussions impenetrable to outsiders, and if they were discovered and charged, they bribed witnesses liberally.

Although Tom would drink with the customers, Moll always remained sober, looking out for trouble from the drunken patrons. While Moll, with the assistance of the hired bouncers, managed to curb the worst of the behaviour, there were still frequent fights on the premises and occasionally the violence spilled out into the surrounding area. In 1736, four men who had just left the coffee house disrupted a mass in the chapel of the Sardinian Ambassador, and in 1737, two of the bouncers, Edward and Noah Bethune, were charged with assault.

By 1739, the Kings had acquired an estate at Haverstock Hill, close to Hampstead Heath, and had built a villa and two houses. Tom King died the same year from alcoholism.

Moll King's Coffee House

On Tom's death, the coffee house became known as Moll King's Coffee House, but business continued much as before. Moll, however, took to drinking and became more quarrelsome, and the reputation of the shacks for bad behaviour and violence worsened. Moll would also occasionally fleece inebriated patrons by littering their tables with broken crockery and then presenting them a bill for the damages, confident that they were too drunk to realise that they were being taken advantage of. The patronage of fashionable society continued though: on one occasion, even George II paid a visit, accompanied by his equerry Viscount Gage, but having been challenged to a fight for admiring the companion of one of his neighbours (who had not recognised him), he left immediately.

Eventually, in June 1739, a riot erupted in the Long Room and spilled out in the piazza. Moll was charged, found guilty, and fined £200, sentenced to three months in prison and required to find sureties for her good behaviour for three years after her release. Moll refused to pay the fine on the grounds that it was both excessive and unwarranted and managed to get it reduced to £50. She suffered little from her stay in prison: her nephew William King took over the running of the coffee house and, by bribing the guards, Moll managed to enjoy many of the comforts of home. She continued to run the coffee house until around 1745, when she retired to live in her villa at Haverstock Hill.

She died on 17 September 1747, leaving a large fortune.

See also

References

- Burford, E.J. (1986). Wits, Wenchers and Wantons - London's Low Life: Covent Garden in the Eighteenth Century. Hale. ISBN 0-7090-2629-3.

- Pelzer, J.; Pelzer, L. (October 1982). "Coffee Houses of Augustan London". History Today. 51 (5): 47.

51°30′43″N 0°7′20″W / 51.51194°N 0.12222°W / 51.51194; -0.12222

Categories: