"Trusts and estates" redirects here. For the journal, see Trusts & Estates (journal).

English trust law concerns the protection of assets, usually when they are held by one party for another's benefit. Trusts were a creation of the English law of property and obligations, and share a subsequent history with countries across the Commonwealth and the United States. Trusts developed when claimants in property disputes were dissatisfied with the common law courts and petitioned the King for a just and equitable result. On the King's behalf, the Lord Chancellor developed a parallel justice system in the Court of Chancery, commonly referred as equity. Historically, trusts have mostly been used where people have left money in a will, or created family settlements, charities, or some types of business venture. After the Judicature Act 1873, England's courts of equity and common law were merged, and equitable principles took precedence. Today, trusts play an important role in financial investment, especially in unit trusts and in pension trusts (where trustees and fund managers invest assets for people who wish to save for retirement). Although people are generally free to set the terms of trusts in any way they like, there is a growing body of legislation to protect beneficiaries or regulate the trust relationship, including the Trustee Act 1925, Trustee Investments Act 1961, Recognition of Trusts Act 1987, Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, Trustee Act 2000, Pensions Act 1995, Pensions Act 2004 and Charities Act 2011.

Trusts are usually created by a settlor, who gives assets to one or more trustees who undertake to use the assets for the benefit of beneficiaries. As in contract law no formality is required to make a trust, except where statute demands it (such as when there are transfers of land or shares, or by means of wills). To protect the settlor, English law demands a reasonable degree of certainty that a trust was intended. To be able to enforce the trust's terms, the courts also require reasonable certainty about which assets were entrusted, and which people were meant to be the trust's beneficiaries.

English law, unlike that of some offshore tax havens and of the United States, requires that a trust have at least one beneficiary unless it is a "charitable trust". The Charity Commission monitors how charity trustees perform their duties, and ensures that charities serve the public interest. Pensions and investment trusts are closely regulated to protect people's savings and to ensure that trustees or fund managers are accountable. Beyond these expressly created trusts, English law recognises "resulting" and "constructive" trusts that arise by automatic operation of law to prevent unjust enrichment, to correct wrongdoing or to create property rights where intentions are unclear. Although the word "trust" is used, resulting and constructive trusts are different from express trusts because they mainly create property-based remedies to protect people's rights, and do not merely flow (like a contract or an express trust) from the consent of the parties. Generally speaking, however, trustees owe a range of duties to their beneficiaries. If a trust document is silent, trustees must avoid any possibility of a conflict of interest, manage the trust's affairs with reasonable care and skill, and only act for purposes consistent with the trust's terms. Some of these duties can be excluded, except where the statute makes duties compulsory, but all trustees must act in good faith in the best interests of the beneficiaries. If trustees breach their duties, the beneficiaries may make a claim for all property wrongfully paid away to be restored, and may trace and follow what was trust property and claim restitution from any third party who ought to have known of the breach of trust.

History

Main articles: History of equity and trusts and History of English land lawAristotle, Nicomachean Ethics (350 BC) Book V, pt 10"The same thing, then, is just and equitable, and while both are good the equitable is superior. What creates the problem is that the equitable is just, but not the legally just but a correction of legal justice. The reason is that all law is universal but about some things it is not possible to make a universal statement which shall be correct.... And this is the nature of the equitable, a correction of law where it is defective owing to its universality.... the man who chooses and does such acts, and is no stickler for his rights in a bad sense but tends to take less than his share though he has the law on his side, is equitable, and this state of character is equity".

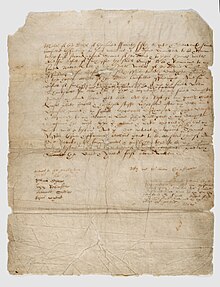

Statements of equitable principle stretch back to the Ancient Greeks in the work of Aristotle, while examples of rules analogous to trusts were found in the Roman law testamentary institution of the fideicommissum, and the Islamic proprietary institution of the Waqf. However, English trusts law is a largely indigenous development that began in the Middle Ages, from the time of the 11th and 12th century crusades. After William the Conqueror became King in 1066, one "common law" of England was created. Common law courts regarded property as an indivisible entity, as it had been under Roman law and continental versions of civil law. During the crusades, landowners who went to fight would transfer title to their land to a person they trusted so that feudal services could be performed and received, but many who returned found that the people they entrusted refused to transfer their title deed back. Sometimes, common law courts would not acknowledge that anybody had rights in the property except the holder of the legal title deeds. So claimants petitioned the King to sidestep the common law courts. The King delegated hearing of petitions to his Lord Chancellor, who established the Court of Chancery as more cases were heard. Where it appeared "inequitable" (i.e. unfair) to let someone with legal title hold onto land, the Lord Chancellor could declare that the real owner "in equity" (i.e. in all fairness) was another person, if this is what good conscience dictated. The Court of Chancery determined that the true "use" or "benefit" of property did not belong to the person on the title (or the feoffee who held seisin). The cestui que use, the owner in equity, could be a different person. So English law recognised a split between legal and equitable owner, between someone who controlled title and another for whose benefit the land would be used. It was the beginning of trust law. The same logic was useful for Franciscan friars, who would transfer title of land to others as they were precluded from holding property by their vows of poverty. When the courts said that one person's legal title to property was subject to an obligation to use that property for another person, there was a trust.

During the 15th century and 16th century, "uses" or "trusts" were also employed to avoid the payment of feudal taxation. If a person died, the law stated a landlord was entitled to money before the land passed to an heir, and the landlord got all of the property under the doctrine of escheat if there were no heirs. Transferring title to a group of people for common use could ensure this never happened, because if one person died he could be replaced, and it was unlikely for all to die at the same time. King Henry VIII saw that this deprived the Crown of revenue, and so in the Statute of Uses 1535 he attempted to prohibit uses, stipulating all land belonged in fact to the cestui que use. Henry VIII also increased the role of the Court of Star Chamber, a court with criminal jurisdiction that invented new rules as it thought fit, and often this was employed against political dissidents. However, when Henry VIII was gone, the Court of Chancery held that the Statute of Uses 1535 had no application where land was leased. People started entrusting property again for family legacies. Moreover, the primacy of equity over the common law soon was reasserted, and this time supported by King James I in 1615, in the Earl of Oxford's case. Due to its deep unpopularity the "criminal equity" jurisdiction was abolished by the Habeas Corpus Act 1640. Trusts grew more popular, and were tolerated by the Crown, as new sources of revenue from the mercantile exploits in the New World decreased the Crown's reliance on feudal dues. By the early 18th century, the use had formalised into a trust: where land was settled to be held by a trustee, for the benefit of another, the Courts of Chancery recognised the beneficiary as the true owner in equity.

By the late 17th century, it had become an ever more widely held view that equitable rules and the law of trusts varied unpredictably, as the jurist John Selden remarked, according to the size of the "Chancellor's foot". Over the 18th century English property law, and trusts with it, mostly came to a standstill in legislation, but the Court of Chancery continued to develop equitable principles notably under Lord Nottingham (from 1673–1682), Lord King (1725–1733), Lord Hardwicke (1737–1756), and Lord Henley (1757–1766). In 1765, the first Professor of English law, William Blackstone wrote in his Commentaries on the Laws of England that equity should not be seen as a distinct body of rules, separate from the other laws of England. For example, although it was "said that a court of equity determines according to the spirit of the rule and not according to the strictness of the letter," wrote Blackstone, "so also does a court of law" and the result was that each system of courts was attempting to reach "the same principles of justice and positive law". Blackstone's influence reached far. Chancellors became more concerned to standardise and harmonise equitable principles. At the start of the 19th century in Gee v Pritchard, referring to John Selden's quip, Lord Eldon (1801–1827) said 'Nothing would inflict upon me greater pain in quitting this place than the recollection that I had done anything to justify the reproach that the equity of this court varies like the Chancellor's foot.' The Court of Chancery was meant to have mitigated the petty strictnesses of the common law of property, but instead came to be seen as cumbersome and arcane. This was partly because until 1813, there was only the Lord Chancellor and the Master of the Rolls working as judges. Work was slow. In 1813, a Vice-Chancellor was appointed, in 1841 two more, and in 1851 two Lord Justices of Appeal in Chancery (making seven). But this did not save it from ridicule. In particular, Charles Dickens (1812–1870), who himself worked as a clerk near Chancery Lane, wrote Bleak House in 1853, depicting a fictional case of Jarndyce v Jarndyce, a Chancery matter about wills that nobody understood and dragged on for years and years. Within twenty years, separate courts of equity were abolished. Parliament merged the common law and equity courts into one system with the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873. Equitable principles would prevail over common law rules in case of conflict, but the separate identity of equity had ended. The separate identity of the trust, however, continued as strongly as before. In other parts of the Commonwealth (or the British Empire at the time) trust law principles, as then understood, were codified for the purpose of easy administration. The best example is the Indian Trusts Act 1882, which described a trust as meaning "an obligation annexed to the ownership of property, and arising out of a confidence reposed in and accepted by the bearer".

Over the 20th century, trusts came to be used for multiple purposes beyond the classical role of parcelling out wealthy families' estates, wills, or charities. First, as more working-class people became more affluent, they began to be able to save for retirement through occupational pensions. After the Old Age Pensions Act 1908, everyone who worked and paid National Insurance would probably have access to the minimal state pension, but if people wanted to maintain their living standards, they would need more. Occupational pensions would typically be constituted through a trust deed, after being bargained for by a trade union under a collective agreement. After World War Two, the number of people with occupational pensions rose further, and gradually regulation was introduced to ensure that people's "pension promise" was protected. The settlor would usually be the employer and employee jointly, and the savings would be transferred to a trustee for the benefit of the employee. Most regulation, especially after the Robert Maxwell scandals and the Goode Report, was directed at ensuring that the employer cannot dominate, or abuse its position through undue influence over the trustee or the trust fund. The second main use of the trust came to be in other financial investments, though not necessarily for retirement. The unit trust, since their launch in 1931, became a popular vehicle for holding "units" in a fund that would invest in various assets, such as company shares, gilts or government bonds or corporate bonds. One person investing alone might not have much money to spread the risk of his or her investments, and so the unit trust offered an attractive way to pool many investors wealth, and share the profits (or losses). Nowadays, unit trusts have been mostly superseded by Open-ended investment companies, which do much the same thing, but are companies selling shares, rather than trusts. Nevertheless, trusts are widely used, and notorious in offshore trusts in "tax havens", where people hire an accountant or lawyer to make an argument that shifting assets in some new way will avoid tax. The third main contemporary use of the trust has been in the family home, though not as an expressly declared trust. As gender inequality began to narrow, both partners to a marriage would often be contributing money, or work, to pay the mortgage, make their home, or raise children together. A number of members of the judiciary became active from the late 1960s in declaring that even if one partner was not on the legal title deeds, she or he would still have an equitable property interest in the home under a "resulting trust" or (more normally today) a "constructive trust". In essence the courts would acknowledge the existence of a property right, without the trust being expressly declared. Some courts said it reflected an implicit common intention, while others said the use of the trust reflected the need to do justice. In this way, trusts continued to fulfill their historical function of mitigating strict legal rules in the interests of equity.

Formation of express trusts

See also: Trust law, United States trust law, Hague Trust Convention, Express trusts, Creation of express trusts in English law, and English land law

In its essence the word "trust" applies to any situation where one person holds property on behalf of another, and the law recognises obligations to use the property for the other's benefit. The primary situation in which a trust is formed is through the express intentions of a person who "settles" property. The "settlor" will give property to someone he trusts (a "trustee") to use it for someone he cares about (a "beneficiary"). The law's basic requirement is that a trust was truly "intended", and that a gift, bailment or agency relationship was not. In addition to requiring certainty about the settlor's intention, the courts suggest the terms of the trust should be sufficiently certain particularly regarding the property and who is to benefit. The courts also have a rule that a trust must ultimately be for people, and not for a purpose, so that if all beneficiaries are in agreement and of full age they may decide how to use the property themselves. The historical trend of construction of trusts is to find a way to enforce them. If, however, the trust is construed as being for a charitable purpose, then public policy is to ensure it is always enforced. Charitable trusts are one of a number of specific trust types, which are regulated by the Charities Act 2006. Very detailed rules also exist for pension trusts, for instance under the Pensions Act 1995, particularly to set out the legal duties of pension trustees, and to require a minimum level of funding.

Intention and formality

See also: Creation of legal relations in English law, Formalities in English law, and Secret trusts in English law

Much like a contract, express trusts are usually formed based on the expressed intentions of a person who owns some property to in future have it managed by a trustee, and used for another person's benefit. Often the courts see cases where people have recently died, and expressed a wish to use property for another person, but have not used legal terminology. In principle, this does not matter. In Paul v Constance, Mr Constance had recently split up with his wife, and began to live with Ms Paul, who he played bingo with. Because of their close relationship, Mr Constance had often repeated that the money in his bank account, partly from bingo winnings and from a workplace accident, was "as much yours as mine". When Mr Constance died, his old wife claimed the money still belonged to her, but the Court of Appeal held that despite the lack of formal wording, and though Mr Constance had retained the legal title to the money, it was held on trust for him and Ms Paul. As Scarman LJ put it, they understood "very well indeed their own domestic situation", and even though legal terms were not used in substance this did "convey clearly a present declaration that the existing fund was as much" belonging to Ms Paul. As Lord Millett later put it, if someone "enters into arrangements which have the effect of creating a trust, it is not necessary that he should appreciate that they do so." The only thing that needs to be done further is that, if the settlor is not declaring herself or himself as the trustee, the property should be physically transferred to the new trustee for the trust to be properly "constituted". The traditional reason for requiring a transfer of property to the trustee was that the doctrine of consideration demanded that property should be passed, and not just promised at some future date, unless something of value was given in return. The general trend in more recent cases, though is to be flexible in these requirements, because as Lord Browne-Wilkinson said, equity "will not strive officiously to defeat a gift".

| Trust formality sources | |

|---|---|

| Companies Act 2006 s 113 and LRA 2002 s 4 | |

| Milroy v Lord EWHC Ch J78 | |

| T Choithram International SA v Pagarani [2000] UKPC 46 | |

| Re Rose EWCA Civ 4 | |

| Mascall v Mascall (1984) 50 P&CR 119 | |

| Pennington v Waine EWCA Civ 227 | |

| Strong v Bird (1874) LR 18 Eq 315 | |

| Law of Property Act 1925 s 53(1)(b) and (2) | |

| Rochefoucauld v Boustead 1 Ch 196 | |

| Bannister v Bannister 2 All ER 133 | |

| Wills Act 1837 s 9 | |

| Wallgrave v Tebbs (1855) 2 K & J 313 | |

| Re Snowden 1 Ch 700 | |

| Ottaway v Norman 2 WLR 50 | |

| Law of Property Act 1925 s 53(1)(c) | |

| Re Vandervell’s Trusts (No 2) Ch 269 | |

| see Formality in English law |

Although trusts do not, generally, require any formality to be established, formality may be required in order to transfer property the settlor wishes to entrust. There are six particular situations which have returned to the cases: (1) transfers of company shares require registration, (2) trusts and transfers of land require writing and registration, (3) transfers (or "dispositions") of an equitable interest require writing, (4) wills require writing and witnesses, (5) gifts that are only to be transferred in the future require deeds, and (6) bank cheques usually need to be endorsed with a signature. The modern view of formal requirements is that their purpose is to ensure the transferring party has genuinely intended to carry out the transaction. As the American lawyer, Lon Fuller, put it the purpose is to provide "channels for the legally effective expression of intention", particularly where there's a common danger in large transactions that people could rush into it without thinking. However, older case law saw the courts interpreting the requirements of form very rigidly. In an 1862 case, Milroy v Lord, a man named Thomas Medley signed a deed for Samuel Lord to hold 50 Bank of Louisiana shares on trust for his niece, Eleanor Milroy. But the Court of Appeal in Chancery held that this did not create a trust (and nor was any gift effective) because the shares had not finally been registered. Similarly, in an 1865 case, Jones v Lock, Lord Cottenham LC held that because a £900 cheque was not endorsed, it could not be counted as being held on trust for his son. This was so even though the father had said "I give this to baby... I am going to put it away for him... he may do what he likes with it" and locked it in a safe. However, the more modern view, starting with Re Rose was that if the transferor had taken sufficient steps to demonstrate their intention for property to be entrusted, then this was enough. Here, Eric Rose had filled out forms to transfer company shares to his wife, and three months later this was entered into the company share register. The Court of Appeal held, however, that in equity the transfer took place when the forms were completed. In Mascall v Mascall (1984) the Court of Appeal held that, when a father filled out a deed and certificate for the transfer of land, although the transfer had not actually been lodged with HM Land Registry, in equity the transfer was irrevocable. The trend was confirmed by the Privy Council in T Choithram International SA v Pagarani (2000), where a wealthy man publicly declared he would donate a large sum of money to a charitable foundation he had set up, but died before any transfer of the money took place. Although a gift, which is not transferred, was traditionally thought to require a deed to be enforced, the Privy Council advised this was not necessary as the property was already vested in him as a trustee, and his intentions were clear. In the case of "secret trusts", where someone has written a will but also privately told the executor that they wished to donate their some part of their property in other ways, this has long been held to not contravene the Wills Act 1837 requirements for writing, because it simply works as a declaration of trust before the will. The modern trend, then, has been that so long as the purpose of the formality rules will not be undermined, the courts will not hold trusts invalid.

Certainty of subject and beneficiaries

| Certainty of subject cases | |

|---|---|

| Sprange v Barnard (1789) 2 Bro CC 585 | |

| Boyce v Boyce (1849) 16 Sim 476 | |

| Palmer v Simmonds (1854) 2 Drew 221 | |

| Re Golay’s Will Trusts 1 WLR 969 | |

| Re Kayford Ltd 1 WLR 279 | |

| Re London Wine Co (Shippers) Ltd PCC 121 | |

| Hunter v Moss EWCA Civ 11 | |

| Re Goldcorp Exchange Ltd UKPC 3 | |

| Sale of Goods Act 1979 ss 16-20B | |

| Re Harvard Securities EWHC Comm 371 | |

| White v Shortall NSWC 1379 | |

| Pearson v Lehman Brothers Finance SA EWCA Civ 1544 | |

| In re Lehman Brothers International (Europe) UKSC 6 | |

| Certainty and English trusts law |

Beyond the requirement for a settlor to have truly intended to create a trust, it has been said since at least 1832 that the subject matter of the property, and the people who are to benefit must also be certain. Together, certainty of intention, the certainty of subject matter and beneficiaries have been called the "three certainties" required to form a trust, although the purposes of each "certainty" are different in kind. While certainty of intention (and the formality rules) seek to ensure that the settlor truly intended to benefit another person with his or her property, the requirements of certain subject matter and beneficiaries focus on whether a court will have a reasonable ability to know on what terms the trust should be enforced. As a point of general principle, most courts do not strive to defeat trusts on the basis of uncertainty. In the case of In re Roberts a lady named Miss Roberts wrote in her will that she wanted to leave £8753 and 5 shillings worth of bank annuities to her brother and his children who had the surname of "Roberts-Gawen". Miss Roberts' brother had a daughter who changed her name on marriage, but her son later changed his name back to Roberts-Gawen. At first instance, Hall VC held that, because the grand-nephew's mother had changed the name it was too uncertain that Miss Roberts had wished him to benefit. But on appeal, Lord Jessel MR held that

the modern doctrine is not to hold a will void for uncertainty unless it is utterly impossible to put a meaning upon it. The duty of the Court is to put a fair meaning on the terms used, and not, as was said in one case, to repose on the easy pillow of saying that the whole is void for uncertainty.

Although in the 19th century a number of courts were overly tentative, the modern trend, much like in the law of contract, became as Lord Denning put it: that "in cases of contract, as of wills, the courts do not hold the terms void for uncertainty unless it is utterly impossible to put a meaning upon them." For example, in the High Court case of Re Golay's Will Trusts, Ungoed-Thomas J held that a will stipulating that a "reasonable income" should be paid to the beneficiaries, although the amount was not anywhere specified, could be given a clear meaning and enforced by the court. Courts were, he said, "constantly involved in making such objective assessments of what is reasonable" and would ensure "the direction in the will is not ... defeated by uncertainty."

However, the courts have had difficulty in defining appropriate principles for cases where trusts are declared over property that many people have an interest in. This is especially true where the person who possesses that property has gone insolvent. In Re Kayford Ltd a mail order business went insolvent and customers who had paid for goods wanted their money back. Megarry J held that because Kayford Ltd had put its money in a separate account the money was held on trust, and so the customers were not unsecured creditors. By contrast, in Re London Wine Co (Shippers) Ltd., Oliver J held that customers who had bought wine bottles were not entitled to take their wine because no particular bottles had been identified for a trust to arise. A similar view was expressed by the Privy Council in Re Goldcorp Exchange Ltd, where the customers of an insolvent gold bullion reserve business were told that they never had been given particular gold bars, and so were unsecured creditors. These decisions were said to be motivated by the desire to not undermine the statutory priority system in insolvency, although it is not entirely clear why those policy reasons extended to consumers who are usually seen as "non-adjusting" creditors. However, in the leading Court of Appeal decision, Hunter v Moss, there was no insolvency issue. There, Moss had declared himself to be a trustee of 50 out of 950 shares he held in a company, and Hunter sought to enforce this declaration. Dillon LJ held that it did not matter that the 50 particular shares had not been identified or isolated, and they were held on trust. The same result was reached, however, in an insolvency decision by Neuberger J in the High Court, called Re Harvard Securities Ltd, where clients of a brokerage company were held to have had an equitable property interest in share capital held for them as a nominee. The view that appears to have been adopted is that if assets are "fungible" (i.e. swapping them with other will not make much difference) a declaration of trust can be made, so long as the purpose of the statutory priority rules in insolvency are not compromised.

| Certainty of beneficiaries cases | |

|---|---|

| Minshull v Minshull (1737) 26 ER 260 | |

| In re Roberts (1881-82) LR 19 Ch D 520 | |

| Re Gulbenkian’s Settlements UKHL 5 | |

| McPhail v Doulton UKHL 1 | |

| Re Baden’s Deed Trusts (no 2) EWCA Civ 10 | |

| Re Tuck’s Settlement Trusts EWCA Civ 11 | |

| Re Barlow’s Will Trusts 1 WLR 278 | |

| West Yorkshire MCC v District Auditor No 3 RVR 24 | |

| Certainty and English trusts law |

The final "certainty" the courts require is to know to some reasonable degree who the beneficiaries are to be. Again, the courts have become increasingly flexible, and intend to uphold the trust if at all possible. In Re Gulbenkian's Settlements (1970) a wealthy Ottoman oil businessman and co-founder of the Iraq Petroleum Company, Calouste Gulbenkian, had left a will giving his trustees "absolute discretion" to pay money to his son Nubar Gulbenkian, and family, but then also anyone with whom Nubar had "from time to time employed or residing". This provision of the will was challenged (by the other potential beneficiaries, who wanted more themselves) as being too uncertain in regard to who the beneficiaries were meant to be. The House of Lords held that the will was still entirely valid, because even though one might not be able to draw up a definite list of everybody, the trustees and a court could be sufficiently certain, with evidence of anyone who "did or did not" employ or house Nubar. Similarly, this "is or is not test" was applied in McPhail v Doulton. Mr Betram Baden created a trust for the employees, relatives and dependants of his company, but also giving the trustees "absolute discretion" to determine who this was. The settlement was challenged (by the local council that would receive the remainder) on the ground that the idea of "relatives" and "dependants" was too uncertain. The House of Lords held the trust was clearly valid because a court could exercise the relevant power, and would do so "to give effect to the settlor's or testator's intentions." Unfortunately, when the case was remitted to the lower courts to determine what in fact the settlor's intentions were, in Re Baden's Deed Trusts, the judges in the Court of Appeal could not agree. All agreed the trust was sufficiently certain, but Sachs LJ thought it was only necessary to show that there was a "conceptually certain" class of beneficiaries, however small, and Megaw LJ thought a class of beneficiaries had to have "at least a substantial number of objects", while Stamp LJ believed that the court should restrict the definition of "relative" or "dependant" to something clear, such as "next of kin". The Court of Appeal in Re Tuck's Settlement Trusts was more clear. An art publisher who had Jewish background, Baronet Adolph Tuck, wished to create a trust for people who were "of Jewish blood". Because of mixing of faiths and ancestors over generations, this could have meant a very large number of people, but in the view of Lord Denning MR the trustees could simply decide. Also the will had stated that the Chief Rabbi of London could resolve any doubts, and so it was valid for a second reason. Lord Russell agreed, although on this point Eveleigh LJ dissented, and stated that the trust was only valid with Rabbi clause. Divergent views in some cases continued. In Re Barlow's Will Trusts, Browne-Wilkinson J held that concepts (like "friend") could always be restricted, as a last resort, to prevent a trust failing. By contrast in one highly political case, a High Court judge found that the West Yorkshire County Council's plan to make a discretionary trust to distribute £400,000 "for the benefit of any or all of the inhabitants" of West Yorkshire, with the aim to inform people about the effects of the council's impending abolition by Margaret Thatcher's government, failed because it was (apparently) "unworkable". It remained unclear whether some courts' attachment to strict certainty requirements was consistent with the principles of equitable flexibility.

Beneficiary principle

| Trust enforceability cases | |

|---|---|

| Morice v Bishop of Durham EWHC Ch J80 | |

| Saunders v Vautier (1841) EWHC Ch J82 | |

| Re Astor's Settlement Trusts Ch 534 | |

| Re Andrew's Trusts 2 Ch 48 | |

| Re Shaw 1 WLR 729 | |

| Re Endacott EWCA Civ 5 | |

| Re Denley's Trust Deed 1 Ch 373 | |

| Re Osoba EWCA Civ 3 | |

| Recognition of Trusts Act 1987, Sch 1, art 18 | |

| Bermuda Trusts (Special Provisions) Act 1989 ss 12A and 12B | |

| Twinsectra Ltd v Yardley UKHL 12 | |

| Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 1964 ss 1 and 3 | |

| Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 2009 ss 5, 7-11 | |

| Beneficiary principle and English trusts law |

People have a general freedom, subject to statutory requirements and basic fiduciary duties, to design the terms of a trust in the way a settlor deems fit. However English courts have long refused to enforce trusts that only serve an abstract purpose, and are not for the benefit of people. Only charitable trusts, defined by the Charities Act 2011, and about four other small exceptions will be enforced. The main reason for this judicial policy is to prevent, as Roxburgh J said in Re Astor's Settlement Trusts, "the creation of large funds devoted to non-charitable purposes which no court and no department of state can control". This followed a similar policy to the rule against perpetuities, which rendered void any trust that would only be transferred to (or "vest") in someone in the distant future (currently 125 years under the Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 2009). In both ways, the view has remained strong that the wishes of the dead should not, so to speak, rule the living from the grave. It would mean that society's resources and wealth would be tied into uses that (because they were not charitable) failed to serve contemporary needs, and therefore made everyone poorer. Re Astor's ST itself concerned the wish of the Viscount Waldorf Astor, who had owned The Observer newspaper, to maintain "good understanding... between nations" and "the independence and integrity of newspapers". While perhaps laudable, it was not within the tightly defined categories of a charity, and so was not valid. An example of a much less laudable aim in Brown v Burdett was an old lady's demand in her will that her house be boarded up for 20 years with "good long nails to be bent down on the inside", but for some reason with her clock remaining inside. Bacon VC cancelled the trust altogether. But while there is a policy against enforcing trusts for abstract and non-charitable purposes, if possible the courts will construe a trust as being for people where they can. For example, in Re Bowes an aristocrat named John Bowes left £5,000 in his will for "planting trees for shelter on the Wemmergill estate", in County Durham. This was an extravagantly large sum of money for trees. But rather than holding it void (since planting trees on private land was a non-charitable purpose) North J construed the trust to mean that the money was really intended for the estate owners. Similarly in Re Osoba, the Court of Appeal held that a trust of a Nigerian man, Patrick Osoba, said to be for the purpose of "training of my daughter" was not an invalid purpose trust. Instead it was in substance intended that the money be for the daughter. Buckley LJ said the court would treat "the reference to the purpose as merely a statement of the testator's motive in making the gift".

There are commonly said to be three (or maybe four) small exceptions to the rule against enforcing non-charitable purpose trusts, and there is one certain and major loophole. First, trusts can be created for building and maintaining graves and funeral monuments. Second, trusts have been allowed for the saying of private masses. Third, it was (long before the Hunting Act 2004) said to be lawful to have a trust promoting fox hunting. These "exceptions" were said to be fixed in Re Endacott, where a minor businessman in who lived in Devon wanted to entrust money "for the purpose of providing some useful memorial to myself". Lord Evershed MR held this invalid because it was not a grave, let alone charitable. It has, however, been questioned whether the existing categories are in fact true exceptions given that graves and masses could be construed as trusts which ultimately benefit the landowner, or the relevant church. In any case the major exception to the no purpose trust rule is that in many other common law countries, particularly the United States and a number of Caribbean states, they can be valid. If capital is entrusted under the rules of other jurisdictions the Recognition of Trusts Act 1987 Schedule 1, articles 6 and 18 requires that the trusts are recognised. This follows the Hague Trust Convention of 1985, which was ratified by 12 countries. The UK recognises any offshore trusts unless they are "manifestly incompatible with public policy". Even trusts in countries that are "offshore financial centres" (typically described as "tax havens" because wealthy individuals or corporations shift their assets there to avoid paying taxes in the UK), purpose trusts can be created which serve no charitable function, or any function related to the good of society, so long as the trust document specifies someone to be an "enforcer" of the trust document. These include Jersey, the Isle of Man, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands. It is argued, for example by David Hayton, a former UK academic trust lawyer who was recruited to serve on the Caribbean Court of Justice, that having an enforcer resolves any problem of ensuring that the trust is run accountably. This substitutes for the oversight that beneficiaries would exercise. The result, it is argued, is that English law's continued prohibition on non-charitable purpose trusts is antiquated and ineffective, and is better removed so that money remains "onshore". This would also have the consequence, like in the US or the tax haven jurisdictions, that public money would be used to enforce trusts over vast sums of wealth which might never do anything for a living person.

Associations

Associations in English law, Concurrent estate, English contract law, and UK company lawWhile express trusts in a family, charity, pension or investment context are typically created with the intention of benefiting people, property held by associations, particularly those which are not incorporated, was historically problematic. Often associations did not express their property to be held in any particular way and courts had theorised that it was held on trust for the members. At common law, associations such as trade unions, political parties, or local sports clubs were formed through an express or implicit contract, so long as "two or more persons bound together for one or more common purposes". In Leahy v Attorney-General for New South Wales Viscount Simonds in the Privy Council, advised that if property is transferred, for example by gift, to an unincorporated association it is "nothing else than a gift to its members at the date of the gift as joint tenants or tenants in common." He said that if property were deemed to be held on trust for future members, this could be void for violating the rule against perpetuities, because an association could last long into the future, and so the courts would generally deem current members to be the appropriate beneficiaries who would take the property on trust for one another. In the English property law concept, "joint tenancy" meant that people own the whole of a body of assets together, while "tenancy in common" meant that people could own specific fractions of the property in equity (though not law). If that was true, a consequence would have been that property was held on trust for members of an association, and those members were beneficiaries. It would have followed that when members left an association, their share could not be transferred to the other members without violating the requirement of writing in the Law of Property Act 1925 section 53(1) for the transfer of a beneficial interest: a requirement that was rarely fulfilled.

Another way of thinking about associations' property, that came to be the dominant and practical view, was first stated by Brightman J in Re Recher's Will Trusts. Here it was said that, if no words are used that indicate a trust is intended, a "gift takes effect in favour of the existing members of the association as an accretion to the funds which are the subject-matter of the contract". In other words, property will be held according to the members' contractual terms of their association. This matters for deciding whether a gift will succeed or be held to fail, although that possibility is unlikely on any contemporary view. It also matters where an association is being wound up, and there is a dispute over who should take the remaining property. In a recent decision, Hanchett‐Stamford v Attorney‐General Lewison J held that the final surviving member of the "Performing and Captive Animals Defence League" was entitled to the remaining property of the association, although while the association was running any money could not be used for the members' private purposes. On the other hand, if money is donated to an organisation, and specifically intended to be passed onto others, then the end of an association could mean that remaining assets will go back to the people the money came from (on "resulting trust") or be bona vacantia. In Re West Sussex Constabulary's Widows, Children and Benevolent (1930) Fund Trusts, Goff J held that a fund set up for the dependants of police staff, which was being wound up, which had been given money expressly for reason of benefiting dependants (and not to benefit the members of the trust) could not be taken by those members. The rules have also mattered, however for the purpose of taxation. In Conservative and Unionist Central Office v Burrell it was held that the Conservative Party, and its various limbs and branches, was not all bound together by a contract, and so not subject to corporation tax.

Charitable trusts

Main article: Charitable trusts in English lawCharitable trusts are a general exception to the rule in English law that trusts cannot be created for an abstract purpose. The meaning of a charity has been set in statute since the Elizabethan Charitable Uses Act 1601, but the principles are now codified by the Charities Act 2011. Apart from being capable of not having any clear beneficiaries, charitable trusts usually enjoy exemption from taxation on its own capital or income, and people making gifts can deduct the gift from their taxes. Classically, a trust would be charitable if its purpose was promoting reduction of poverty, advancement of education, advancement of religion, or other purposes for the public benefit. The criterion of "public benefit" was the key to being a charity. Courts gradually added specific examples, today codified in the CA 2011 section 3, section 4 emphasises that all purposes must be for the "public benefit". The meaning remains with the courts. In Oppenheim v Tobacco Securities Trust the House of Lords held that an employer's trust for his employees and children was not for the public benefit because of the personal relationship between them. Generally, the trust must be for a "sufficient section of the public" and cannot exclude the poor. However it is often unclear how these principles are applicable in practice.

Because beneficiaries can rarely enforce charitable trustee standards, the Charities Commission is a statutory body whose role is to promote good practice and pre-empt poor charitable management.

Pension and investment trusts

Main articles: Pensions in the UK, Unit trust, Investment trust, Investment fund, and Taxation of trusts (United Kingdom)Pension trusts are the most economically significant kind of trust, totalling over £3 trillion worth of retirement savings in the UK in 2021. Other forms of trusts in investment include mutual funds, unit trusts, and investment trusts though these are commonly organised as companies and hold money on trust for many people. Pensions are often organised as companies and hold money on trust for beneficiaries who are people at work. Because workers pay for their savings through their work, often to a fund set up by an employer and a workplace union, the regulation of pensions differs considerably from general trust law. The construction of a pension trust deed must comply with the basic term of mutual trust and confidence in the employment relationship. Employees are entitled to be informed by their employer about how to make the best of their pension rights. Moreover, workers must be treated equally, on grounds of gender or otherwise, in their pension entitlements. The management of a pension trust must be partly codetermined by the pension beneficiaries, so that a minimum of one third of a trustee board are elected or "member nominated trustees". The Secretary of State has the power by regulation, as yet unused, to increase the minimum up to one half. Trustees are charged with the duty to manage the fund in the best interests of the beneficiaries, in a way that reflects their general and ethical preferences, by investing the savings in company shares, bonds, real estate or other financial products. There is a strict prohibition on the misapplication of any assets. Unlike the general position for a trustee's duty of care, the Pensions Act 1995 section 33 stipulates that trustee investment duties may not be excluded by the trust deed.

Because pension schemes save up significant amounts of money, which many people rely on in retirement, protection against an employer's insolvency, or dishonesty, or risks from the stock market were seen as necessary after the 1992 Robert Maxwell scandal. Defined contribution funds must be administered separately, not subject to an employer's undue influence. The Insolvency Act 1986 also requires that outstanding pension contributions are a preferential debt over creditors, except those with fixed security. However, defined benefit schemes are also meant to insure everyone has a stable income regardless of whether they live a shorter or longer period after retirement. The Pensions Act 2004 sections 222 to 229 require that pension schemes have a minimum "statutory funding objective", with a statement of "funding principles", whose compliance is periodically evaluated by actuaries, and shortfalls are made up. The Pensions Regulator is the non-departmental body which is meant to oversee these standards, and compliance with trustee duties, which cannot be excluded. However, in The Pensions Regulator v Lehman Brothers the Supreme Court concluded that if the Pensions Regulator issued a "Financial Support Direction" to pay up funding, and it was not paid when a company had gone insolvent, this ranked like any other unsecured debt in insolvency, and did not have priority over banks that hold floating charges. In addition, there exists a Pensions Ombudsman who may hear complaints and take informal action against employers who fall short of their statutory duties. If all else fails, the Pension Protection Fund guarantees a sum is ensured, up to a statutory maximum.

Aside from pensions there are a range of collective investment schemes, including unit trusts, open-ended investment companies, so called "investment trusts", and other mutual funds. In EU and UK law the umbrella term "collective investment scheme" is used to cover a range of legal entities, regardless of their form as trusts, companies or contracts, or a mixture. A "unit trust" is created through a trust deed, and run by a fund manager, where people may buy or sell "units" in a fund that invests in a range of securities. Though constituted as a trust, it is classified by the Corporation Tax Act 2010 section 617 as a company, and units are shares. An open-ended investment company is a company in which people may also buy and sell shares in the underlying investment fund, which is ultimately held on trust for those investors. "Investment trusts" are not actually trusts at all, rather than limited companies, registered with Companies House, and often used as closed-end investment vehicles that are created with a fixed capital. The most significant is the "real estate investment trusts", a kind of entity with tax breaks that was imported from the US, regulated under the Corporation Tax Act 2010 sections 518 to 609. All securities are regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority to ensure transparency and fairness for investors.

Formation of imposed trusts

See also: English unjust enrichment law, English tort law, and Equitable remedies

While express trusts arise primarily because of a conscious plan that settlors, trustees or beneficiaries consent to, courts also impose trusts to correct wrongs and reverse unjust enrichment. The two main types of imposed trusts, known as "resulting" and "constructive" trusts, do not necessarily respond to any intentional wishes. There is significant academic debate over why they arise. Traditionally, the explanation was this was to prevent people acting "unconscionably" (i.e. inequitably or unjustly). Modern authors increasingly prefer to categorise resulting and constructive trusts more precisely, as responding to wrongs, unjust enrichments, sometimes consent or contributions in family home cases. In these contexts, the word "trust" still denotes the proprietary remedy, but resulting and constructive trusts usually do not come from complete agreements. Having a property right is usually most important if a defendant is insolvent, because then the "beneficiaries" under resulting or constructive rank in priority to the defendants' other creditors: they can take the property away first. Generally, resulting trusts are imposed by courts when a person receives property, but the person who transferred it did not have the intention for them to benefit. English law establishes a presumption that people do not desire to give away property unless there is some objective manifestation of consent to do so. Without positive evidence of an intention to transfer property, a recipient holds property under a resulting trust. Constructive trusts arise in around ten different circumstances. Though the list is debated, potentially the courts will "construe" a person to hold property for another person, first, to complete a consent based obligations, particularly those lacking formality, second, to reflect a person's contribution to the value of property, especially in a family home, third, to effect a remedy for wrongdoing such as when a trustee makes a secret profit, and fourth, to reverse unjust enrichment.

Resulting trusts

Main articles: Resulting trust, Resulting trusts in English law, and Quistclose trusts in English lawA resulting trust is usually recognised when one person has given property to another person without the intention to benefit them. The recipient will be declared by the court to be a "resulting trustee" so that the equitable property right returns to the person it came from. For some time, the courts of equity required proof of a positive intention before they would acknowledge the passing of a gift, primarily as a way to prevent fraud. If one person transferred property to another, unless there was positive evidence that it was meant to be a gift, it would be presumed that the recipient held the property on trust for the transferee. It was also recognised that if money was transferred as part of the purchase of land or a house, the transferee would acquire an equitable interest in the land under a resulting trust. On the other hand, if evidence clearly showed a gift was intended, then a gift would be acknowledged. In Fowkes v Pascoe, an old lady named Mrs Baker had bought Mr Pascoe some company stocks, because she had become endeared to him and treated him like a grandson. When she died, the executor, Mr Fowkes, argued that Mr Pascoe held the stocks on resulting trust for the estate, but the Court of Appeal said the fact that the lady had put the stocks in Mr Pascoe's name was absolutely conclusive. The presumption of a resulting trust was rebutted.

If there is no evidence either way of intention to benefit someone with a property transfer, the presumption of a resulting trust is transferred is not absolute. The Law of Property Act 1925 section 60(3) states that a resulting trust does not arise simply with absence of an express intention. However, the presumption is strong. This has a consequence when property is transferred in connection with an illegal purpose. Ordinarily, English law takes the view that one cannot rely in civil claims on actions done that are tainted with illegality (or in the Latin saying ex turpi causa non oritur actio). However, in Tinsley v Milligan, it was still possible for a claimant, Ms Milligan, to show she had an equitable interest in the house where she and her partner, Ms Tinsley, lived because she had contributed to the purchase price. Ms Tinsley was the sole registered owner, and both had intended to keep things this way because with one person on the title, they could fraudulently claim more in social security benefits. The House of Lords held, however, that because a resulting trust was presumed by the law, Ms Milligan did not need to prove an intention to not benefit Ms Tinsley, and therefore rely on her intention that was tainted with an illegal purpose. By contrast, the law has historically stated that when a husband transfers property to his wife (but not vice versa) or when parents make transfers to their children, a gift is presumed (or there is a "presumption of advancement"). This presumption has been criticised on the ground that it is essentially sexist, or at least "belonging to the propertied classes of a different social era." It could be thought to follow that if Milligan had been a man and married to Tinsley, then the case's outcome would be the opposite. One limitation, however, came in Tribe v Tribe. Here a father transferred company shares to his son with a view to putting them out of reach of his creditors. This created a presumption of advancement. His son then refused to give the shares back, and the father argued in court that he had plainly not intended the son should benefit. Millett LJ held that because the illegal plan (to defraud creditors) had not been put into effect, the father could prove he had not intended to benefit his son by referring to the plan. Depending on what an appellate court would now decide, the presumption of advancement may remain a part of the law. The Equality Act 2010 section 199 would abolish the presumption of advancement, but the section's implementation was delayed indefinitely by the Conservative led coalition government when it was elected in 2010.

As well as resulting trusts, where the courts have presumed that the transferor would have intended the property return, there are resulting trusts which arise by automatic operation of the law. A key example is where property is transferred to a trustee, but too much is handed over. The surplus will be held by the recipient on a resulting trust. For example, in the Privy Council case of Air Jamaica Ltd v Charlton an airline's pension plan was overfunded, so that all employees could be paid the benefits that they were due under their employment contracts, but a surplus remained. The company argued that it should receive the money, because it had attempted to amend the scheme's terms, and the Jamaican government argued that it should receive the money, as bona vacantia because the scheme's original terms had stated money was not to return to the company, and the employees had all received their entitlements. However, the Privy Council advised both were wrong and the money should return to those who had made contributions to the fund: half the company and half the employees, on resulting trust. This was in response, according to Lord Millett, "to the absence of any intention on his part to pass a beneficial interest to the recipient." In a similar pattern, it was held in Vandervell v Inland Revenue Commissioners that an option to repurchase shares in a company was held on resulting trust for Mr Vandervell when he declared the option to be held by his family trustees, but did not say who he meant the option to be held on trust for. Mr Vandervell had been trying to make a gift of £250,000 to the Royal College of Surgeons without paying any transfer tax, and thought that he could do it if he transferred the College some shares in his company, let the company pay out enough dividends, and then bought the shares back. However, the Income Tax Act 1952 section 415(2), applied a tax to a settlor of a trust for any income made out of trusts, if the settlor retained any interest whatsoever. Because Mr Vandervell did not say who the option was meant to be for, the House of Lords concluded the option was held on trust for him, and therefore he was taxed. It has also been said, that trusts which arise when one person gives property to another for a reason, but then the reason fails, as in Barclays Bank Ltd v Quistclose Investments Ltd are resulting in nature. However, Lord Millett in his judgment in Twinsectra Ltd v Yardley,(dissenting on the knowing receipt point, leading on the Quistclose point) recategorised the trust which arises as an immediate express trust for the benefit of the transferor, albeit with a mandate upon the recipient to apply the assets for a purpose stated in the contract.

Considerable disagreement exists about why resulting trusts arise, and also the circumstances in which they ought to, since it carries property rights rather than simply a personal remedy. The most prominent academic view is that resulting trust respond to unjust enrichment. However, this analysis was rejected in the controversial speech of Lord Browne-Wilkinson in Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale v Islington LBC. This case involved a claim by the Westdeutsche bank for its money back from Islington council with compound interest. The bank gave the council money under an interest rate swap agreement, but these agreements were found to be unlawful and ultra vires for councils to enter into by the House of Lords in 1992 in Hazell v Hammersmith and Fulham LBC partly because the transactions were speculative, and partly because councils were effectively exceeding their borrowing powers under the Local Government Act 1972. There was no question about whether the bank could recover the principal sum of its money, now that these agreements were void, but at the time the courts did not have jurisdiction to award compound interest (rather than simple interest) unless a claimant showed they were making a claim for property that they owned. So, to get more interest back, the bank contended that when money was transferred under the ultra vires agreement, a resulting trust arose immediately in its favour, giving it a property right, and therefore a right to compound interest. The minority of the House of Lords, Lord Goff of Chieveley and Lord Woolf, held that the bank should have no proprietary claim, but they should nevertheless be awarded compound interest. This view was actually endorsed 12 years later by the House of Lords in Sempra Metals Ltd v IRC so that the courts can award compound interest on debts that are purely personal claims. However, the majority in Westdeutsche held that the bank was not entitled to compound interest at all, particularly because there was no resulting trust. Lord Browne-Wilkinson's reasoning was that only if a recipient's conscience were affected, could a resulting trust arise. It followed that because the council could not have known that its transactions were ultra vires until the 1992 decision in Hazell, its "conscience" could not be affected. Theoretically this was controversial because it was unnecessary to reject that resulting trusts respond to unjust enrichment in order to deny that a proprietary remedy should be given. Not all unjust enrichment claims necessarily require proprietary remedies, while it does appear that explaining resulting trusts as a response to whatever good "conscience" requires is not especially enlightening.

Constructive trusts

Constructive trust and Constructive trusts in English lawAlthough resulting trusts are generally thought to respond to an absence of an intention to benefit another person when property is transferred, and the growing view is that underlying this is a desire to prevent unjust enrichment, there is less agreement about "constructive trusts". At least since 1677, constructive trusts have been recognised in English courts in about seven to twelve circumstances (depending on how the counting and categorisation is done). Because constructive trusts were developed by the Court of Chancery, it was historically said that a trust was "construed" or imposed by the court on someone who acquired property, whenever good conscience required it. In the US case, Beatty v Guggenheim Exploration Co, Cardozo J remarked that the "constructive trust is the formula through which the conscience of equity finds expression. When property has been acquired in such circumstances that the holder of the legal title may not in good conscience retain the beneficial interest, equity converts him into a trustee." However, this did not say what underlay the seemingly different situations where constructive trusts were found. In Canada, the Supreme Court at one point held that all constructive trusts responded to someone being "unjustly enriched" by coming to hold another person's property, but it later changed its mind, given that property could come to be held when it was unfair to keep through other means, particularly a wrong or through an incomplete consensual obligation. It is generally accepted that constructive trusts have been created for reasons, and so the more recent debate has therefore turned on which constructive trusts should be considered as arising to perfect a consent based obligation (like a contract), which ones arise in response to wrongdoing (like a tort) and which ones (if any) arise in response to unjust enrichment, or some other reasons. Consents, wrongs, unjust enrichments, and miscellaneous other reasons are usually seen as being at least three of the main categories of "event" that give rise to obligations in English law, and constructive trusts may straddle all of them.

The constructive trusts that are usually seen as responding to consent (for instance, like a commercial contract), or "intention" are, first, agreements to convey property where all the formalities have not yet been completed. Under the doctrine of anticipation, if an agreement could be specifically enforced, before formalities are completed the agreement to transfer a property is regarded as effective in equity, and the property will be held on trust (unless this is expressly excluded by the agreement's terms). Second, when someone agrees to use property for another's benefit, or divide a property after purchase, but then goes back on the agreement, the courts will impose a constructive trust. In Binions v Evans when Mr and Mrs Binions bought a large property they promised the sellers that Mrs Evans could remain for life in her cottage. They subsequently tried to evict Mrs Evans, but Lord Denning MR held that their agreement had created a constructive trust, and so the property was not theirs to deal with. Third, gifts or trusts that are made without completing all formalities will be enforced under a constructive trust if it is clear that the person making the gift or trust manifested a true intention to do so. In the leading case, Pennington v Waine a lady named Ada Crampton had wished to transfer 400 shares to her nephew, Harold, had filled in a share transfer form and given it to Mr Pennington, the company's auditors, and had died before Mr Pennington had registered it. Ada's other family members claimed the shares still belonged to them, but the Court of Appeal held that even though not formally complete, the estate held the shares on constructive trust for Harold. Similarly, in T Choithram International SA v Pagarani the Privy Council held that Mr Pagarani's estate held money on constructive trust after he died for a new foundation, even though Mr Pagarani had not completed the trust deeds, because he had publicly announced his intention to hold the money on trust. Fourth, if a person who is about to die secretly declares that he wishes property to go to someone not named in a will, the executor holds that property on constructive trust. Similarly, fifth, if a person writes a "mutual will" with their partner, agreeing that their property will go to a particular beneficiary when they both die, the surviving person cannot simply change their mind and will hold the property on constructive trust for the party who was agreed.

It is more controversial whether "constructive trusts" in the family home respond to consent or intention, or really respond to contributions to property, which are usually found in the "miscellaneous" category of events that generate obligations. In a sixth situation, constructive trusts have been acknowledged to arise since the late 1960s, where two people are living together in a family home, but are not married, and both are making financial or other contributions to the house, but only one is registered on the legal title. The law had settled in Lloyds Bank plc v Rosset as requiring saying that (1) if an agreement had been made for both to share in the property, then a constructive trust would be imposed in favour of the person who was not registered, or (2) they had nevertheless made direct contributions to the purchase of the home or mortgage repayments, then they would have a share of the property under a constructive trust. However, in Stack v Dowden, and then Jones v Kernott the Law Lords held by a majority that Rosset probably no longer represented the law (if it ever did) and that a "common intention" to share in the property could be inferred from a wide array of circumstances (including potentially simply having children together), and also perhaps "imputed" without any evidence. However, if a constructive trust, and a property right binding third parties, arises in this situation based on imputed intentions, or simply on the basis that it was fair, it would mean that constructive trusts did not merely respond to consent, but also to the fact of valuable contributions being made. There remains significant debate both about the proper manner of characterising constructive trusts in this field, and also about how far the case law should match the statutory regime that applies for married couples under the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973.

Situations where constructive trusts arise

- Specifically enforceable agreements, before transfer completed

- Undertakings by purchasers to use property for another's benefit

- Clearly intended gifts or trusts, short of formality

- "Secret" trusts declared before a will

- Mutual wills

- Contributions to the family home, through money or work

- On proceeds of crime

- For information acquired in breach of confidence

- On profits made by a fiduciary acting in breach of duty

- In some cases where a recipient of property is unjustly enriched

Constructive trusts arise in a number of situations that are generally classified as "wrongs", in the sense that they mirror a breach of duty by a trustee, by someone who owes fiduciary obligations, or anyone. In a seventh group of constructive trust cases (which also seems uncontroversial), a person who murders their wife or husband cannot inherit their property, and are said by the courts to hold any property on constructive trust for another next of kin. Eighth, it was held in Attorney General v Guardian Newspapers Ltd that information, or intellectual property, taken in breach of confidence would be held on constructive trust. Ninth, a trustee or another person in a fiduciary position, who breaches a duty and makes a profit out of it, has been held to hold all profits on constructive trust. For instance in Boardman v Phipps, a solicitor for a family trust and one of the trust's beneficiaries, took the opportunity to invest in a company in Australia, partly on the trust's behalf, but also making a profit themselves. They both stood in a "fiduciary" position of trust because as a solicitor, or someone managing the trust's affairs, the law requires they act solely in the trust's interest. Crucially, they failed to gain the fully informed consent of the beneficiaries to invest in the opportunity and make a profit themselves. This opened up a possibility that their interests could conflict with the interests of the trust. So, the House of Lords held they were in breach of duty, and that all profits they made were held on constructive trust, though they could claim quantum meruit (a salary fixed by the court) for the work they did. More straightforwardly, in Reading v Attorney-General the House of Lords held that an army sergeant (a fiduciary for the UK government) who took bribes while stationed in Egypt held his bribes on constructive trust for the Crown. However, more recently it has become more controversial to classify these constructive trusts along with wrongs on the basis that the remedies that are available should differ from (and usually go further than) compensatory damages in tort. Also, it has been doubted that a constructive trust should be imposed that would bind third parties in an insolvency situation. In Sinclair Investments (UK) Ltd v Versailles Trade Finance Ltd, Lord Neuberger MR held that company's liquidators could not claim a proprietary interest in the fraudulent profits its former director had made if this would prejudice the director's other creditors in insolvency. The effect of a constructive trust would accordingly be limited so that it did not bind third party creditors of an insolvent defendant. The United Kingdom Supreme Court, however, has subsequently overruled Sinclair in FHR European Ventures LLP v Cedar Capital Partners LLC, holding that a bribe or secret commission accepted by an agent is held on trust for his principal..

Unjust enrichment is seen to underlie a final group of constructive trust cases, although this remains controversial. In Chase Manhattan Bank NA v Israel-British Bank (London) Ltd Goulding J held that a bank that mistakenly paid money to another bank had a claim to the money back under a constructive trust. Mistake would typically be seen as an unjust enrichment claim today, and there is no debate over whether the money could be claimed back in principle. It was, however, questioned whether the claim for the money back should be proprietary in nature, and so whether a constructive trust should arise, particularly if this would bind third parties (for instance, if the recipient bank had gone insolvent). In Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale v Islington LBC Lord Browne-Wilkinson held that a constructive trust could only arise if the recipient's conscience would have been affected at the time of the receipt or before any third party's rights had intervened. In this way, it is controversial whether unjust enrichment underlies any constructive trusts at all, although it remains unclear why someone's conscience being affected should make any difference.

Content

Once a trust has been validly formed, the trust's terms guide its operation. While professionally drafted trust instruments often contain a full description of how trustees are appointed, how they should manage the property, and their rights and obligations, the law supplies a comprehensive set of default rules. Some were codified in the Trustee Act 2000 but others are construed by the courts. In many instances, English law follows a laissez-faire philosophy of "freedom of trust". In general, it will be left to the choice of the settlor to follow the law or to draft alternative rules. Where a trust instrument runs out or is silent, the law will fill the gaps. In contrast, in specific trusts, particularly pensions within the Pensions Act 1995, charities under the Charities Act 2011, and investment trusts regulated by the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, many rules regarding trusts' administration, and the duties of trustees are made mandatory by statute. This reflects the view of Parliament that beneficiaries in those cases lack bargaining power and need protection, especially through enhanced disclosure rights. For family trusts, or private unmarketed trusts, the law can usually be contracted around, subject to an irreducible core of trust obligations. The scope of compulsory terms may be subject of debate, but Millett LJ in Armitage v Nurse viewed that every trustee must always act "honestly and in good faith for the benefit of the beneficiaries". In addition to general principles of good administration, trustees' primary duties include fulfilling a duty of "undivided loyalty" by avoiding any possibility of a conflict of interest, exercising proper care, and following the terms of the trust to fulfil their purpose.

Administration

| Trust administration sources | |

|---|---|

| Trustee Act 1925 ss 25, 31-36 and 57 | |

| Saunders v Vautier (1841) 4 Beav 115 | |

| Trustee Act 2000 ss 11 and 15 | |

| Trustee Act 2000 ss 28-32 | |

| Re Duke of Norfolk’s Settlement Trusts Ch 61 | |

| Re Londonderry's Settlement Ch 918 | |

| Schmidt v Rosewood Trust Ltd UKPC 26 | |

| see Fiduciary duty and English trusts law |

Possibly the most important aspect of good trust management is having good trustees. In virtually all cases, a settlor will have identified who the trustees will be. Even if they have not or if the chosen trustees refuse, a court will, in the last resort, appoint one under the Public Trustee Act 1906. A court may also replace trustees who are acting detrimentally to the trusts.

Once a trust is running, Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act 1996 section 19 allows beneficiaries of full capacity to determine who the new trustees are, if other replacement procedures are not in the trust document. This is, however, simply an articulation of the general principle from Saunders v Vautier that beneficiaries of full age and sound mind may, by consensus, dissolve the trust or do with the property as they wish.

According to the Trustee Act 2000 sections 11 and 15, a trustee may not delegate their power to distribute trust property without liability, but they may delegate administrative functions and the power to manage assets if accompanied by a policy statement. If they do, they can be exempt from negligence claims. As for the trust terms, these may be varied in any unforeseen emergency, but only in relation to the trustee's management powers, not a beneficiary's rights.

The Variation of Trusts Act 1958 allows courts to vary trust terms, particularly on behalf of minors, people not yet entitled, or those with remoter interests under a discretionary trust. For the latter group of people, who may have highly restricted rights or know very little about trust terms, the Privy Council affirmed in Schmidt v Rosewood Trust Ltd that courts have an inherent jurisdiction to administer trusts, especially when a requirement for information about a trust needs to be disclosed.

Trustees, especially in family trusts, may often be expected to perform their services for free. However, more commonly, a trust will make provision for some payment. In the absence of terms in the trust instrument, the Trustee Act 2000 sections 28–32 stipulate that professional trustees are entitled to a "reasonable remuneration." All trustees, agents, nominees, and custodians may be reimbursed for expenses from the trust fund as well. The courts have additionally stated in Re Duke of Norfolk's Settlement Trusts that there is a power to pay a trustee more for unforeseen but necessary work. Otherwise, all payments must be explicitly authorized to avoid the strict rule against any possibility of conflicts of interest.

Duty of loyalty

| Duty of loyalty cases | |

|---|---|

| Morley v Morley (1678) 22 ER 817 | |

| Keech v Sandford EWHC Ch J76 | |

| Bray v Ford AC 44 | |

| Armitage v Nurse Ch 241 | |

| Bristol and West Building Society v Mothew 1 Ch 1 | |

| Meinhard v Salmon, 164 NE 545 (NY 1928) | |

| Boardman v Phipps 2 AC 46 | |

| Holder v Holder Ch 353 | |

| Parker v McKenna (1874) 10 Ch App 96 | |

| see Fiduciary duty and English trusts law |

The core duty of a trustee is to pursue the interests of the beneficiaries, or anyone else the trust permits, except the interests of the trustee himself. Put positively, this is described as the "fiduciary duty of loyalty". The term "fiduciary" simply means someone in a position of trust and confidence, and because a trustee is the core example of this, English law has for three centuries consistently reaffirmed that trustees, put negatively, may have no possibility of a conflict of interest. Shortly after the United Kingdom was formed, it had its first stock market crash in the South Sea Bubble, a crash where corrupt directors, trustees or politicians ruined the economy. Soon after, the Chancery Court decided Keech v Sandford. On a much smaller scale than the recent economic collapse, Keech claimed he was entitled to the profits his trustee, Sandford, had made by buying the lease on a market in Romford, now in East London. While Keech was still an infant, Sandford alleged he had been told by the market landlord that there would be no renewal for a child beneficiary. Only then, alleged Sandford, did he inquire and contract to purchase the lease in his own name. Lord King LC held this was irrelevant, because no matter how honest, the consequences of allowing a relaxed approach to trustee duties would be worse.

This may seem hard, that the trustee is the only person of all mankind who might not have the lease: but it is very proper that rule should be strictly pursued, and not in the least relaxed; for it is very obvious what would be the consequence of letting trustees have the lease, on refusal to renew to cestui que use.