| This article is an orphan, as no other articles link to it. Please introduce links to this page from related articles; try the Find link tool for suggestions. (November 2015) |

| Non Charoen โนนเจริญ | |

|---|---|

| Subdistrict municipality | |

| |

| Coordinates: 14°48′5″N 103°18′53″E / 14.80139°N 103.31472°E / 14.80139; 103.31472 | |

| Country | |

| Province | Buriram |

| Amphoe | Ban Kruat |

| Tambon | Tambon Non Charoen |

| Government | |

| • Type | Local government |

| • Mayor | Somjai Khamapanya |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8.370 sq mi (21.679 km) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 8,456 |

| • Density | 1,006.3/sq mi (388.53/km) |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (Thailand Standard Time) |

| Area code | 0 4461 6192 |

| Website | www |

Non Charoen' (Thai: โนนเจริญ) is a subdistrict municipality (thesaban tambon) in Thailand, The town covers the whole tambon Non Charoen of Ban Kruat district. The town is the main economic center of Buriram Province

See also

References

External links

This Buriram Province location article is a stub. You can help Misplaced Pages by expanding it. |

| This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. You can assist by editing it. (November 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "sandbox" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

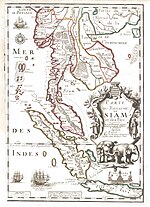

| Siamสยาม | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1238–1932 | |||||||

Flag (1855-1916)

Flag (1855-1916)

Coat of arms

Coat of arms

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Capital | Sukhothai(1238-1382) Phitsanulok(1382-1438) Ayutthaya(1351-1767) Thonburi(1767-1782) Bangkok (Krung Thep) | ||||||

| Common languages | Thai | ||||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism | ||||||

| Government | Absolute Monarchy | ||||||

| King | |||||||

| • 1279-1298 | Ramkhamhaeng | ||||||

| • 1590-1605 | Naresuan | ||||||

| • 1656-1688 | Narai | ||||||

| • 1767-1782 | Taksin | ||||||

| • 1782-1809 | Buddha Yodfa Chulaloke | ||||||

| • 1868-1910 | Chulalongkorn | ||||||

| Legislature | Supreme Council of State of Siam (from 1925 to 1932) | ||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages to Modern Ages | ||||||

| • Foundation of the Kingdom of Sukhothai | 1238 | ||||||

| • Rise of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya | 1351 | ||||||

| • Fall of Ayutthaya | 1767 | ||||||

| • Build of Thonburi | 1768 | ||||||

| • Foundation of the Rattanakosin Kingdom at Bangkok | April 1782 | ||||||

| • European Colonialism Invasion | Mid 19 Century - Early 20 Century | ||||||

| • Siamese Revolution of 1932 | 1932 | ||||||

| Currency | Pot Duang(until 1897),Baht | ||||||

| |||||||

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Thailand | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Timeline

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Siam (Thai: สยาม) was the name of a series of Kingdoms situated in the center of mainland Southeast Asia, known today as Thailand. According to various foreign sources, The Kingdom of Siam was referred to Ayutthaya from the sixteenth century to the eighteenth century.Bangkok, the new capital was later referred as Siam. In 1932, the government of Siam officially changed the name of the country to Thailand. According to foreign accounts, foreigners called the Kingdom of Ayutthaya as Siam but local people called themselves as Tai. Chinese sources also call it Xian, or Xian Luo Guo.

Origin

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Prior to the southwards migration of the Tai people from Yunnan in the tenth century, the Indochina peninsula or mainland Southeast Asia had been a home to various indigenous animistic communities for as far back as 500,000 years ago. The recent discovery of Homo erectus fossils such as Lampang man is but one example. The remains were first discovered during excavations in Lampang province, Thailand. The finds have been dated from roughly 1,000,000-500,000 years ago in the Pleistocene. Historians agree that the diverse Austro-Asiatic groups that inhabited the Indochina peninsula are related to the people which today inhabit the islands of the Pacific. As these peoples dispersed along the Gulf of Thailand, Malay Peninsula and Malay Archipelago, they inhabited the coastal areas of the archipelago as well as other remote islands. The seafarers possessed advanced navigation skills, sailing as far as New Zealand, Hawaii and Madagascar.

The most well known pre-historic settlement in Thailand is often associated to the major archaeological site at Ban Chiang; dating of artifacts from this site is a consensus that at least by 1500 BC, the inhabitants had developed bronze tools and also grew rice. There are myriad sites in Thailand dating to the Bronze (1500 BC-500 BC) and Iron Ages (500 BC-AD 500). The most thoroughly researched of these sites are located in the country's Northeast, especially in the Mun and Chi River valleys. The Mun River in particular is home to many 'moated' sites which comprise mounds surrounded by ditches and ramparts. The mounds contain evidence of prehistoric occupation. Around the first century of the Christian era, according to Funan epigraphy and the records of Chinese historians(Coedes), a number of trading settlements of the South appear to have been organized into several Indianised states, among the earliest of which are believed to be Langkasuka and Tambralinga.

Dvaravadee, or Dvaravati, was also referred to a group of city-states rising from the coast of Andaman Sea, the western side of the present Gulf of Thailand, up to the lower Chao Phraya River valley. With the archaeological remains, Dvaravadee bore heavily Indian and Sri Lankan influence; Hinduism and Buddhism. Their artistic style are unique and different from the Angkorian pattern. Dvaravadee apparently faded to the expansion of Angkor rising later.

Angkor Rule

Funan, Chenla, Angkor apparently expanded their power and influence over most of mainland Southeast Asia. Local city-states and kingdoms accepted more powerful Angkor regime until the thirteenth century. Sukhothai, a Tai kingdom in upper Chao Phraya River valley gradually began independent. In the fourteenth century, a powerful, new city-state in the lower Chao Phraya Basin later known as Ayutthaya, came into existence. Due to series of attacks, Ayutthaya Kingdom eventually put an end to Angkor in the fifteenth century.

Sukhothai and Lanna

Main article: Sukhothai kingdom Main article: LannaThai city-states gradually became independent from the weaker Khmer Empire in Angkor Thom. It is said that Sukhothai was established as a sovereign, strong kingdom by Pho Khun, Lord Father, Sri Indraditya in 1238. A political feature 'positively' called by 'classic' or mainstream Thai historians as, 'father governs children' existed at this time. According to details in stone inscriptipn, people could bring their problems to the king directly; as there was a bell in front of the palace for this purpose. The city briefly dominated the area under King Ramkhamhaeng, who established the Thai alphabet, but after his death in 1365 it fell into decline and became subject to another emerging Thai state, Ayutthaya kingdom, in the lower Chao Phraya area.

Another Thai state that coexisted with Sukhothai was the northern state of Lanna, centered in Chiangmai. King Phya Mangrai was its founder. This state emerged in the same period as Sukhothai. Evidently Lanna became closed ally of Sukhothai. When Ayutthaya kingdom had emerged and expanded its influence from the Chao Phraya valley, Sukhothai was finally subdued. Fierce battles between Lanna and Ayutthaya had constantly took place. Chiangmai was eventually subjugated, becoming Ayutthaya's 'vassal'.

Lanna's independent history ended in 1558, when it finally fell to the Burmese; thereafter it was dominated by Burma until late eigthteenth century. Local leaders rose up against the Burmese with the help of the rising Thai kingdom of Thonburi king Taksin. The 'Northern City-States' then became vassals of the lower Thai kingdoms of Thonburi and Bangkok. In early twentieth century they were annexed and became part of modern Siam, or Thailand.

The kings of Sukhothai

- King Pho Khun Sri Indraditya (1249- 1257)

- King Pho Khun Ban Muang (1257 - 1277)

- King Pho Khun Ramkhamhaeng (Ramkhamhaeng the Great) (ruled 1277 - 1298 or 1317) (called Rammaraj in the Ayutthaya chronicles)

- King Pu Phraya Si Songklam: After Ramkhamheang's death, ruled temporarily in absence of Loethai who was on trip to China. He was not styled Pho Khun. (Not counted as a King)

- King Pho Khun Loethai (1298 - 1347)

- King Pho Khun Nguanamthom (1347)

- King Phya Lithai or Thammaracha I (1347 - 1368/1374)

- King Thammaracha II or Phya Leuthai (1368/1374 - 1399)

- King Thammaracha III or Phya Saileuthai (1399 - 1419)

- King Thammaracha IV (1419 - 1438)

Ayutthaya

Main article: Ayutthaya kingdomAyutthaya Kingdom has its location on a small inlet, circled by three rivers. Due to its superior location, Ayutthaya quickly became powerful, politically and economically. Ayutthaya had different, various names ranging from 'Ayothaya', derived from Ayodhya, an Indian holy city,'Krung Thep', 'Phra Nakorn' and 'Dvaravati'.

The first ruler of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya, King Ramathibodi I, made two important contributions to Thai history: the establishment and promotion of Theravada Buddhism as the official religion – to differentiate his kingdom from the neighbouring Hindu kingdom of Angkor – and the compilation of the Dharmashastra, a legal code based on Hindu sources and traditional Thai custom. The Dharmashastra remained a tool of Thai law until late in the 19th century. However, Ayutthaya was plagued by internal fighting

Ayutthaya's tradition became the model for later period, Bangkok's Chakri Dynasty.

Beginning with the Portuguese in the 16th century, Ayutthaya, known to the Europeans as 'Kingdom of Siam', had some contact with the West. It became one of the most prosperous cities in East Asia. Dutch and French were among the most active foreigners in the kingdom as well as Chinese and Japanese.

Ayutthaya expanded its sphere over a considerable area, ranging from the Islamic states on the Malay Peninsula, the Andaman ports, to states in northern Thailand. In the 18th century, Ayutthaya Kingdom was gradually in decline as fighting between princes and officials had plagued its political arena. Outlying principalities became more and more independent, ignoring the capital's orders and decrees.

In the 1700s, the last phase of the kingdom arrived. The Burmese, who had control of Lanna and had also unified their kingdom under a powerful dynasty, launched several invasion attempts in the 1750s and 1760s. Finally, in 1767, the Burmese attacked the capital city and conquered it. The royal family fled the city where the king died of starvation ten days later. The Ayutthaya royal line had been extinguished. Overall there are 33 kings in this period, including an unofficial king.

There were 5 dynasties during Ayutthaya period:

- U-Thong Dynasty which consists of 3 kings

- Suphanabhumi Dynasty consisting of 13 kings

- Sukhothai Dynasty consisting of 7 kings

- Prasart Thong (Golden Tower) Dynasty consisting of 4 kings

- Bann Plu Dynasty consisting of 6 kings

List of rulers of Ayutthaya

Uthong Dynasty ราชวงศ์อู่ทอง(first reign, 1350-1370)

- Ramathibodi I (formerly Prince U Thong) (1350 - 1369)

- Ramesuan (1369 - 1370) (first rule, abdicated)

Suphannaphum Dynasty ราชวงศ์สุพรรณภูมิ (first reign, 1370-1388)

- Borommaracha I (Pha Ngua) (1370 - 1388)

- Thong Lan (1388)

Uthong Dynasty ราชวงศ์อู่ทอง(second reign, 1388-1409)

- Ramesuan สมเด็จพระราเมศวร (1388 - 1395) (second rule)

- Ramracha Thirat สมเด็จพระรามราชาธิราช (1395 - 1409)

Suphannaphum Dynasty ราชวงศ์สุพรรณภูมิ (second reign, 1409-1569)

- Intha Racha(Nakharinthara Thirat) สมเด็จพระอินทราชา (นครินทราธิราช) (1409 - 1424)

- Borommaracha Thirat II (Sam Phraya) สมเด็จพระบรมราชาธิราชที่ 2 (เจ้าสามพระยา) (1424 - 1448)

- Boromma Trailokanat สมเด็จพระบรมไตรโลกนาถ (1448 - 1488)

- Borommaracha Thirat III สมเด็จพระบรมราชาธิราชที่ 3 (1488 - 1491)

- Ramathibodi II (Chettha Thirat) สมเด็จพระรามาธิบดีที่ 2 (พระเชษฐาธิราช) (1491 - 1529)

- Borommaracha Thirat IV (Nor Phutthangkun) สมเด็จพระบรมราชาธิราชที่ 4 (หน่อพุทธางกูร) (1529 - 1533)

- Ratsadathiratcha Kuman พระรัษฎาธิราชกุมาร (1533); child king

- Chaiya Racha Thirat สมเด็จพระไชยราชาธิราช (1534 - 1546)

- Kaeo Fa (Yot Fa) พระแก้วฟ้า (พระยอดฟ้า) (joint regent 1546-1548); child king & Queen Si Sudachan

- Vạravoṇśādhirāj ขุนวรวงศาธิราช (1548)

- Phra Maha Chakkraphat สมเด็จพระมหาจักรพรรดิ (ruled 1548-1568) & Queen Suriyothai สมเด็จพระศรีสุริโยทัย (d.1548)

- Mahinthara Thirat สมเด็จพระมหินทราธิราช (1568 - 1569)

Sukhothai Dynasty ราชวงศ์สุโขทัย(1569-1629)

- Maha Thammaracha Thirat (Sanphet I) สมเด็จพระมหาธรรมราชาธิราช (สมเด็จพระเจ้าสรรเพชญ์ที่ 1) (1569 - 1590)

- Naresuan, the Great (Sanphet II) สมเด็จพระนเรศวรมหาราช (สมเด็จพระเจ้าสรรเพชญ์ที่ 2) (1590 - 1605)

- Ekathotsarot (Sanphet III) สมเด็จพระเอกาทศรถ (สมเด็จพระเจ้าสรรเพชญ์ที่ 3) (1605 - 1610)

- Si Saowaphak (Sanphet IV) พระศรีเสาวภาคย์ (สมเด็จพระเจ้าสรรเพชญ์ที่ 4) (1610 - 1611)

- Drongdharm (Intha Racha) สมเด็จพระเจ้าทรงธรรม (พระอินทราชา) (1611 - 1628)

- Chejthathraj สมเด็จพระเชษฐาธิราช (1628 - 1629)

- Artitthayawongs สมเด็จพระอาทิตยวงศ์ (1629)

Prasat Thong Dynasty ราชวงศ์ปราสาททอง(1630-1688)

- Prasat Thong (Sanphet V) สมเด็จพระเจ้าปราสาททอง (สมเด็จพระเจ้าสรรเพชญ์ที่ 5) (1630 - 1655)

- Chao Fa Chai (Sanphet VI) สมเด็จเจ้าฟ้าไชย (สมเด็จพระเจ้าสรรเพชญ์ที่ 6) (1655)

- Si Suthammaracha (Sanphet VII) สมเด็จพระศรีสุธรรมราชา (สมเด็จพระเจ้าสรรเพชญ์ที่ 7) (1655)

- Narai, the Great สมเด็จพระนารายณ์มหาราช (1656 - 1688)

Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty ราชวงศ์บ้านพลูหลวง(1688-1767)

- Phet Racha สมเด็จพระเพทราชา (1688 - 1703)

- Luang Sorasak or Phrachao Sua ('The Tiger King') (Sanphet VIII) สมเด็จพระเจ้าสรรเพชญ์ที่ 8 (หลวงสรศักดิ์ - พระเจ้าเสือ) (1703 - 1709)

- Tai Sa (Sanphet IX) สมเด็จพระเจ้าสรรเพชญ์ที่ 9 (พระเจ้าท้ายสระ) (1709 - 1733)

- Borommakot (Borommaracha Thirat III) สมเด็จพระเจ้าอยู่หัวบรมโกศ (สมเด็จพระบรมราชาธิราชที่ 3) (1733 - 1758)

- Uthumphon (Borommaracha Thirat IV) สมเด็จพระเจ้าอุทุมพร (1758)

- Suriyamarin or Ekkathat (Borommaracha Thirat V) สมเด็จพระเจ้าอยู่หัวพระที่นั่งสุริยามรินทร์ (พระเจ้าเอกทัศ) (1758 - 1767)

After Ayutthaya Period

From 1768 to 1932 the area of modern Thailand was dominated by Siam, an absolute monarchy with capitals briefly at Thonburi and later at Rattanakosin, both in modern-day Bangkok. The first half of this period was a time of consolidation of the kingdom's power, and was punctuated by periodic conflicts with Burma, Vietnam and Laos. The later period was one of engagement with the colonial powers of Britain and France, in which Siam managed to be the only southeast Asian country not to be colonised by a European country. Internally the kingdom developed into a centralised nation state with borders defined by its interaction with the Western powers. Significant economic and social progress was made, with an increase in foreign trade, the abolition of slavery and the expansion of education to the emerging middle class. However, there was no substantial political reform until the monarchy was overthrown in a military coup in 1932.

Thonburi period

| It has been suggested that this section be merged into Thonburi Kingdom. (Discuss) |

In 1767, after dominating southeast Asia for almost 400 years, the Ayutthaya kingdom was brought down by invading Burmese armies, its capital burned, and its territory occupied by the invaders.

Despite its complete defeat and occupation by Burma, Siam made a rapid recovery. The resistance to Burmese rule was led by a noble of Chinese descent, Taksin, a capable military leader. Initially based at Chanthaburi in the south-east, within a year he had defeated the Burmese occupation army and re-established a Siamese state with its capital at Thonburi on the west bank of the Chao Phraya, 20 km from the sea. In 1768 he was crowned as King Taksin (now officially known as Taksin the Great). He rapidly re-united the central Thai heartlands under his rule, and in 1769 he also occupied western Cambodia. He then marched south and re-established Siamese rule over the Malay Peninsula as far south as Penang and Terengganu. Having secured his base in Siam, Taksin attacked the Burmese in the north in 1774 and captured Chiang Mai in 1776, permanently uniting Siam and Lanna. Taksin's leading general in this campaign was Thong Duang, known by the title Chaophraya Chakri. In 1778 Chakri led a Siamese army which captured Vientiane and re-established Siamese domination over Laos.

Despite these successes, by 1779 Taksin was in political trouble at home. He seems to have developed a religious mania, alienating the powerful Buddhist monkhood by claiming to be a sotapanna or divine figure. He also attacked the Chinese merchant class, and foreign observers began to speculate that he would soon be overthrown. In 1782 Taksin sent his armies under Chakri to invade Cambodia, but while they were away a rebellion broke out in the area around the capital. The rebels, who had wide popular support, offered the throne to Chakri. Chakri marched back from Cambodia and deposed Taksin, who was secretly executed shortly after. Chakri ruled under the name Ramathibodi (he was posthumously given the name Phutthayotfa Chulalok), but is now generally known as King Rama I, first king of the Chakri dynasty. One of his first decisions was to move the capital across the river to the village of Bang Makok (meaning "place of olive plums"), which soon became the city of Bangkok. The new capital was located on the island of Rattanakosin, protected from attack by the river to the west and by a series of canals to the north, east and south. Siam thus acquired both its current dynasty and its current capital.

Bangkok period

Rama I

Rama I restored most of the social and political system of the Ayutthaya kingdom, promulgating new law codes, reinstating court ceremonies and imposing discipline on the Buddhist monkhood. His government was carried out by six great ministries headed by royal princes. Four of these administered particular territories: the Kalahom the south; the Mahatthai the north and east; the Phrakhlang the area immediately south of the capital; and the Krommueang the area around Bangkok. The other two were the ministry of lands (Krom Na) and the ministry of the royal court (Krom Wang). The army was controlled by the King's deputy and brother, the Uparat. The Burmese, seeing the disorder accompanying the overthrow of Taksin, invaded Siam again in 1785. Rama allowed them to occupy both the north and the south, but the Uparat led the Siamese army into western Siam and defeated the Burmese in a battle near Kanchanaburi. This was the last major Burmese invasion of Siam, although as late as 1802 Burmese forces had to be driven out of Lanna. In 1792 the Siamese occupied Luang Prabang and brought most of Laos under indirect Siamese rule. By the time of his death in 1809 Rama I had created a Siamese Empire dominating an area considerably larger than modern Thailand.

Rama II

The reign of Rama I's son Phuttaloetla Naphalai (now known as King Rama II) was relatively uneventful. The Chakri family now controlled all branches of Siamese government — since Rama I had 42 children, his brother the Uparat had 43 and Rama II had 73, there was no shortage of royal princes to staff the bureaucracy, the army, the senior monkhood and the provincial governments. (Most of these were the children of concubines and thus not eligible to inherit the throne.) But during Rama II's reign western influences again began to be felt in Siam. In 1785 the British occupied Penang, and in 1819 they founded Singapore. Soon the British displaced the Dutch and Portuguese as the main western economic and political influence in Siam. The British objected to the Siamese economic system, in which trading monopolies were held by royal princes and businesses were subject to arbitrary taxation. In 1821 the government of British India sent a mission to demand that Siam lift restrictions on free trade — the first sign of an issue which was to dominate 19th century Siamese politics.

Rama III

Rama II died in 1824 and was peacefully succeeded by his son Chetsadabodin, who reigned as King Nangklao, now known as Rama III. Rama II's younger son, Mongkut, was ordered to become a monk to remove him from politics.

In 1825 the British sent another mission to Bangkok. They had by now annexed southern Burma and were thus Siam's neighbours to the west, and they were also extending their control over Malaya. The King was reluctant to give in to British demands, but his advisors warned him that Siam would meet the same fate as Burma unless the British were accommodated. In 1826, therefore, Siam concluded its first commercial treaty with a western power. Under the treaty, Siam agreed to establish a uniform taxation system, to reduce taxes on foreign trade and to abolish some of the royal monopolies. As a result, Siam's trade increased rapidly, many more foreigners settled in Bangkok, and western cultural influences began to spread. The kingdom became wealthier and its army better armed.

A Lao rebellion led by Anouvong was defeated in 1827, following which Siam destroyed Vientiane, carried out massive forced population transfers from Laos to the more securely held area of Isan, and divided the Lao mueang into smaller units to prevent another uprising. In 1842– Rama III's most visible legacy in Bangkok is the Wat Pho temple complex, which he enlarged and endowed with new temples.

Rama III regarded his brother Mongkut as his heir, although as a monk Mongkut could not openly assume this role. He used his long sojourn as a monk to acquire a western education from French and American missionaries, one of the first Siamese to do so. He learned English and Latin, and studied science and mathematics. The missionaries no doubt hoped to convert him to Christianity, but in fact he was a strict Buddhist and a Siamese nationalist. He intended using this western knowledge to strengthen and modernise Siam when he came to the throne, which he did in 1851. By the 1840s it was obvious that Siamese independence was in danger from the colonial powers: this was shown dramatically by the British Opium Wars with China in 1839–1842. In 1850 the British and Americans sent missions to Bangkok demanding the end of all restrictions on trade, the establishment of a western-style government and immunity for their citizens from Siamese law (extraterritoriality). Rama III's government refused these demands, leaving his successor with a dangerous situation.

Mongkut

Mongkut came to the throne as Rama IV in 1851, determined to save Siam from colonial domination by forcing modernisation on his reluctant subjects. But although he was in theory an absolute monarch, his power was limited. Having been a monk for 27 years, he lacked a base among the powerful royal princes, and did not have a modern state apparatus to carry out his wishes. His first attempts at reform, to establish a modern system of administration and to improve the status of debt-slaves and women, were frustrated. Rama IV thus came to welcome western pressure on Siam. This came in 1855 in the form of a mission led by the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir John Bowring, who arrived in Bangkok with demands for immediate changes, backed by the threat of force. The King readily agreed to his demand for a new treaty, called the Bowring Treaty, which restricted import duties to 3%, abolished royal trade monopolies, and granted extraterritoriality to British subjects. Other western powers soon demanded and got similar concessions.

The king soon came to consider that the real threat to Siam came from the French, not the British. The British were interested in commercial advantage, the French in building a colonial empire. They occupied Saigon in 1859, and 1867 established a protectorate over southern Vietnam and eastern Cambodia. Rama IV hoped that the British would defend Siam if he gave them the economic concessions they demanded. In the next reign this would prove to be an illusion, but it is true that the British saw Siam as a useful buffer state between British Burma and French Indochina.

Chulalongkorn

Rama IV died in 1868, and was succeeded by his 15-year-old son Chulalongkorn, who reigned as Rama V and is now known as Rama the Great. Rama V was the first Siamese king to have a full western education, having been taught by a British governess, Anna Leonowens - whose place in Siamese history has been fictionalised as The King and I. At first Rama V's reign was dominated by the conservative regent, Chaophraya Si Suriyawongse, but when the king came of age in 1873 he soon took control. He created a Privy Council and a Council of State, a formal court system and budget office. He announced that slavery would be gradually abolished and debt-bondage restricted.

At first the princes and other conservatives successfully resisted the king's reform agenda, but as the older generation was replaced by younger and western-educated princes, resistance faded. The king could always argue that the only alternative was foreign rule. He found powerful allies in his brothers Prince Chakkraphat, whom he made finance minister, Prince Damrong, who organized interior government and education, and his brother-in-law Prince Devrawongse, foreign minister for 38 years. In 1887 Devrawonge visited Europe to study government systems. On his recommendation the king established Cabinet government, an audit office and an education department. The semi-autonomous status of Chiang Mai was ended and the army was reorganised and modernised.

Territorial claims abandoned by Siam in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

In 1893 the French authorities in Indochina used a minor border dispute to provoke a crisis. French gunboats appeared at Bangkok, and demanded the cession of Lao territories east of the Mekong. The King appealed to the British, but the British minister told the King to settle on whatever terms he could get, and he had no choice but to comply. Britain's only gesture was an agreement with France guaranteeing the integrity of the rest of Siam. In exchange, Siam had to give up its claim to the Tai-speaking Shan region of north-eastern Burma to the British.

The French, however, continued to pressure Siam, and in 1906–1907 they manufactured another crisis. This time Siam had to concede French control of territory on the west bank of the Mekong opposite Luang Prabang and around Champasak in southern Laos, as well as western Cambodia. The British interceded to prevent more French bullying of Siam, but their price, in 1909 was the acceptance of British sovereignty over of Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis and Terengganu under Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909. All of these "lost territories" were on the fringes of the Siamese sphere of influence and had never been securely under their control, but being compelled to abandon all claim to them was a substantial humiliation to both king and country (historian David K. Wyatt describes Chulalongkorn as "broken in spirit and health" following the 1893 crisis). In the early twentieth century these crises were adopted by the increasingly nationalist government as symbols of the need for the country to assert itself against the West and its neighbours.

Meanwhile, reform continued apace transforming an absolute monarchy based on relationships of power into a modern, centralised nation state. The process was increasingly under the control of Rama V's sons, who were all educated in Europe. Railways and telegraph lines united the previously remote and semi-autonomous provinces. The currency was tied to the gold standard and a modern system of taxation replaced the arbitrary exactions and labour service of the past. The biggest problem was the shortage of trained civil servants, and many foreigners had to be employed until new schools could be built and Siamese graduates produced. By 1910, when the King died, Siam had become at least a semi-modern country, and continued to escape colonial rule.

Vajiravudh and the ascent of elite nationalism

One of Rama V's reforms was to introduce a western-style law of royal succession, so in 1910 he was peacefully succeeded by his son Vajiravudh, who reigned as Rama VI. He had been educated at Sandhurst military academy and at Oxford, and was an anglicised Edwardian gentleman. Indeed one of Siam's problems was the widening gap between the westernised royal family and upper aristocracy and the rest of the country. It took another 20 years for western education to extend to the rest of the bureaucracy and the army: a potential source of conflict.

There had been some political reform under Rama V, but the king was still an absolute monarch, who acted as his own prime minister and staffed all the agencies of the state with his own relatives. Vajiravudh, with his British education, knew that the rest of the nation could not be excluded from government for ever, but he was no democrat. He applied his observation of the success of the British monarchy, appearing more in public and instituting more royal ceremonies. But he also carried on his father's modernisation programme. Polygamy was abolished, primary education made compulsory, and in 1916 higher education came to Siam with the founding of Chulalongkorn University, which in time became the seedbed of a new Siamese intelligentsia.

Another solution he found was to establish the Wild Tiger Corps, a paramilitary organisation of Siamese citizens of "good character" united to further the nation's cause. The King spent much time on the development of the movement as he saw it as an opportunity to create a bond between himself and loyal citizens; a volunteer corps willing to make sacrifices for the king and the nation and as a way to single out and honor his favorites.

At first the Wild Tigers were drawn from the king's personal entourage (it is likely that many joined in order to gain favour with Vajiravudh), but an enthusiasm among the population arose later.

Of the movement, a German observer wrote in September 1911:

This is a troop of volunteers in black uniform, drilled in a more or less military fashion, but without weapons. The British Scouts are apparently the paradigm for the Tiger Corps. In the whole country, at the most far-away places, units of this corps are being set up. One would hardly recognise the quiet and phlegmatic Siamese.

Vajiravudh's style of government differed from that of his father. In the beginning of the sixth reign, the king continued to use his father's team and there was no sudden break in the daily routine of government. Much of the running of daily affairs was therefore in the hands of experienced and competent men. To them and their staff Siam owed many progressive steps, such as the development of a national plan for the education of the whole populace, the setting up of clinics where free vaccination was given against smallpox, and the continuing expansion of railways.

However, senior posts were gradually filled with omembers of the King's coterie when a vacancy occurred through death, retirement, or resignation. By 1915, half the cabinet consisted of new faces. Most notable was Chao Phraya Yomarat's presence and Prince Damrong's absence. He resigned from his post as Minister of the Interior officially because of ill health, but in actuality because of friction between himself and the king.

In 1917 Siam declared war on Germany, mainly to gain favour with the British and the French. Siam's token participation in World War I secured it a seat at the Versailles Peace Conference, and Foreign Minister Devawongse used this opportunity to argue for the repeal of the 19th century treaties and the restoration of full Siamese sovereignty. The United States obliged in 1920, while France and Britain delayed until 1925. This victory gained the king some popularity, but it was soon undercut by discontent over other issues, such as his extravagance, which became more noticeable when a sharp postwar recession hit Siam in 1919. There was also the fact that the king had no son; he obviously preferred the company of men to women (a matter which of itself did not much concern Siamese opinion, but which did undermine the stability of the monarchy because of the absence of heirs).

Thus when Rama VI died suddenly in 1925, aged only 44, the monarchy was already in a weakened state. He was succeeded by his younger brother Prajadhipok.

Prajadhipok

Unprepared for his new responsibilities, all Prajadhipok had in his favour was a lively intelligence, a certain diplomacy in his dealings with others, a modesty and industrious willingness to learn, and the somewhat tarnished, but still potent, magic of the crown.

Unlike his predecessor, the king diligently read virtually all state papers that came his way, from ministerial submissions to petitions by citizens. Within half a year only three of Vajiravhud's twelve ministers stayed on, the rest having been replaced by members of the royal family. On the one hand, these appointments brought back men of talent and experience, on the other, it signalled a return to royal oligarchy. The King obviously wanted to demonstrate a clear break with the discredited sixth reign, and the choice of men to fill the top positions appeared to be guided largely by a wish to restore a Chulalongkorn-type government.

The initial legacy that Prajadhipok received from his elder brother were problems of the sort that had become chronic in the Sixth Reign. The most urgent of these was the economy: the finances of the state were in chaos, the budget heavily in deficit, and the royal accounts an accountant's nightmare of debts and questionable transactions. That the rest of the world was in deep economic depression following World War I did not help the situation either.

Virtually the first act of Prajadipok as king entailed an institutional innovation intended to restore confidence in the monarchy and government, the creation of the Supreme Council of the State. This privy council was made up of a number of experienced and extremely competent members of the royal family, including the long time Minister of the Interior (and Chulalongkorn's right hand man) Prince Damrong. Gradually these princes arrogated increasing power by monopolising all the main ministerial positions. Many of them felt it their duty to make amends for the mistakes of the previous reign, but it was not generally appreciated.

With the help of this council, the king managed to restore stability to the economy, although at a price of making a significant amount of the civil servants redundant and cutting the salary of those that remained. This was obviously unpopular among the officials, and was one of the trigger events for the coup of 1932.

Prajadhipok then turned his attention to the question of future politics in Siam. Inspired by the British example, the King wanted to allow the common people to have a say in the country's affair by the creation of a parliament. A proposed constitution was ordered to be drafted, but the King's wishes were rejected, perhaps wisely, by his advisers, who felt that the population was not yet ready for democracy.

In 1932, with the country deep in depression, the Supreme Council opted to introduce cuts in official spending, including the military budget. The King foresaw that these policies might create discontent, especially in the army, and he therefore convened a special meeting of officials to explain why the cuts were necessary. In his addressed he stated the following:

I myself know nothing at all about finances, and all I can do is listen to the opinions of others and choose the best... If I have made a mistake, I really deserve to be excused by the people of Siam.

No previous monarch of Siam had ever spoken in such terms. Many interpreted the speech not as Prajadhipok apparently intended, namely as a frank appeal for understanding and cooperation. They saw it as a sign of his weakness and evidence that a system which perpetuated the rule of fallible autocrats should be abolished. Serious political disturbances were threatened in the capital, and in April the king agreed to introduce a constitution under which he would share power with a prime minister. This was not enough for the radical elements in the army, however. On 24 June 1932, while the king was holidaying at the seaside, the Bangkok garrison mutinied and seized power, led by a group of 49 officers known as "the Promoters." Thus ended 150 years of Siamese absolute monarchy.

Conquest

Thais were always at war with Burmese, Laotian&Cambodian(Khmer) First Thai Empire became independent. Ayutthaya Kingdom sacked Angkor by the end of the fifteenth century. Consequently Ayutthaya became the strongest power in Indochina, but it lacked the manpower to dominate the region. In the last year of his reign, Ramathibodi had seized Angkor during what was to be the first of many successful Thai assaults on the Khmer capital. The policy was aimed at securing Ayutthaya's eastern frontier by preempting Vietnamese designs on Khmer territory. The weakened Khmer periodically submitted to Ayutthaya's suzerainty, but efforts to maintain control over Angkor were repeatedly frustrated. However, Angkor eventually fell. Thai troops were frequently diverted to suppress rebellions in Sukhothai or to campaign against Chiang Mai, where Ayutthaya's expansion was tenaciously resisted. Eventually Ayutthaya subdued the territory that had belonged to Sukhothai, and the year after Ramathibodi died, his kingdom was recognized by the emperor of China's newly established Ming Dynasty as Sukhothai's rightful successor then 15thCentury War with Burma in Chiang Khran until last war with Burma in 19thCentury later Reign of Rama III war with Vietnam until Vietnam became French Colony.

Relationship

Sukhothai

The relation of Thai China was Thais good relation. Thais friendly with Lanna&Phayao. the Thais bad Relationship with Khmer Empire because they lost Thais territory to Thais.

Ayutthaya

Mostly Thais have Enemies is Khmer Empire (later Cambodia). in 14th-15th Century Thais war with Burma all century and Burmese burned Thais city Ayutthaya in 1767.Thais have European contact with Portuguese,French,Dutch Thais have Friendly with Portugal & France in Narai Reign they have relationship to Catholic missionaries to convert Narai to Roman Catholicism.

Cultural

Economy

The Thais never lacked a rich food supply. Peasants planted rice for their own consumption and to pay taxes. Whatever remained was used to support religious institutions. From the thirteenth to the fifteenth century, however, a remarkable transformation took place in Thai rice cultivation. In the highlands, where rainfall had to be supplemented by a system of irrigation that controlled the water level in flooded paddies, the Thais sowed the glutinous rice that is still the staple in the geographical regions of the North and Northeast. But in the floodplain of the Chao Phraya, farmers turned to a different variety of rice—the so-called floating rice, a slender, nonglutinous grain introduced from Bengal—that would grow fast enough to keep pace with the rise of the water level in the lowland fields in Reign of Rama V made Pot Duang into Baht.

Art

Thais have many art such Temple(Wat),Palace(Wang),House(baaan.) some art from Cambodian art such a Stone Castle in Phimai, Phanom Rung, Muang Tam. in Ayutthaya there have some westerner art in Ayutthaya Portugese Catholic Church in Ayutthaya. After Ayutthaya period is characterized by the further development of the Ayutthaya style, rather than by more great innovation. One important element was the Krom Chang Sip Mu (Organization of the Ten Crafts), originally founded in Ayutthaya, which was responsible for improving the skills of the country's craftsmen. Paintings from the mid-19th century show the influence of Western art.

Literature

Thais have many literature such Ramakien,Romance of the Three Kingdoms from China. Phra Aphai Mani by Sunthorn Phu.and other literature.

Religion

Thai Empire Religion was Theravada Buddhism in Ayutthaya Era. Some Muslim States wanted Ayutthayan King to convert to Islam. In 17thCentury France via French Missionaries from China tried to convert him to Roman Catholicism.

End of state

Since Khana Ratsadon took revolution on 24 June 1932 and changed absolute monarchy regime into parliamentary democracy and constitutional monarchy, the state ran riot many times because of government usurpation. Plaek Pibulsonggram as the third prime minister wanted to bring nationalism to people. He renamed the state to Thailand and changed people's nationality from Siamese to Thai on 24 June 1939. However, it was considered that the Siam state ended in 1932 when the regime changed.

References

- "Thailand (Siam ) History" (overview), CS Mngt, 2005, CSMngt.com webpage: CSMngt-Thai.

- Greene, Stephen Lyon Wakeman. Absolute Dreams. Thai Government Under Rama VI, 1910-1925. Bangkok: White Lotus, 1999

- Wyatt, David, Thailand: A Short History, Yale University Press, 1984