Device on vehicle

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A windscreen wiper (Commonwealth English) or windshield wiper (American English) is a device used to remove rain, snow, ice, washer fluid, water, or other debris from a vehicle's front window. Almost all motor vehicles, including cars, trucks, buses, train locomotives, and watercraft with a cabin—and some aircraft—are equipped with one or more such wipers, which are usually a legal requirement.

A wiper generally consists of a metal arm; one end pivots, and the other end has a long rubber blade attached to it. The arm is powered by a motor, often an electric motor, although pneumatic power is also used for some vehicles. The blade is swung back and forth over the glass, pushing water, other precipitation, or any other impediments to visibility from its surface. The speed is usually adjustable on vehicles made after 1969, with several continuous rates and often one or more intermittent settings. Most personal automobiles use two synchronized radial-type arms, while many commercial vehicles use one or more pantograph arms.

On some vehicles, a windscreen washer system is also used to improve and expand the function of the wiper(s) to dry or icy conditions. This system sprays water, or an antifreeze window washer fluid, at the windscreen using several well-positioned nozzles. This system helps remove dirt or dust from the windscreen when used in concert with the wiper blades. When antifreeze washer fluid is used, it can help the wipers remove snow or ice. For these types of winter conditions, some vehicles have additional heaters aimed at the windows, embedded heating wire(s) in the glass, or embedded heating wire(s) in the wiper blade; these defroster systems can melt ice or help to keep snow and ice from building up on the windscreen. Less frequently, miniature wipers are installed on headlights to ensure they function optimally.

History

Early versions

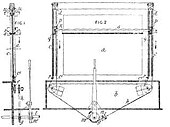

One of the earliest recorded patents for the windscreen wiper is by George J. Capewell of Hartford Connecticut, which was filed on August 6, 1896. His invention was for "windows of slow-moving craft; but it is more particularly adapted and intended for windows of rapidly-moving vehicles, such as high-speed locomotives and cars, with which it is necessary that the observer or driver should have a clear view of the path or track." Similar to current automotive wiper designs, his invention involves "usually two of these wipers, and they can be secured to the frame below the front board of the vehicle or behind the housing surrounding the window in position to be out of sight and in such manner that one will scrape off the heaviest part of the substance collected upon the glass." His patent illustration shows a circular window, although the patent notes "it is not essential that the glass be circular in form."

Other early designs for the windscreen wiper are credited to Polish concert pianist Józef Hofmann, and to Mills Munitions, Birmingham, who also claimed to have been the first to patent windscreen wipers in England. At least three inventors patented windscreen cleaning devices at around the same time in 1903; Mary Anderson, Robert Douglass, and John Apjohn. In April 1911, a patent for windscreen wipers was registered by Sloan & Lloyd Barnes, patent agents of Liverpool, England, for Gladstone Adams of Whitley Bay.

American inventor Mary Anderson is popularly credited with devising the first operational windscreen wiper in 1903. In Anderson's patent, she called her invention a "window cleaning device" for electric cars and other vehicles. Operated via a lever from inside a vehicle, her version of windscreen wipers closely resembles the windscreen wiper found on many early car models. Anderson had a model of her design manufactured, then filed a patent (US 743,801) on June 18, 1903 that was issued to her by the US Patent Office on November 10, 1903.

Irish born inventor James Henry Apjohn (1845–1914) patented an "Apparatus for Cleaning Carriage, Motor Car and other Windows" which was stated to use either brushes or wipers and could be either motor driven or hand driven. The brushes or wipers were intended to clean either both up and down or in just one direction on a vertical window. Apjohn's invention had a priority date in the UK of 9 October 1903.

John R. Oishei (1886-1968) formed the Tri-Continental Corporation in 1917. This company introduced the first windscreen wiper, Rain Rubber, for the slotted, two-piece windscreens found on many of the automobiles of the time. Today Trico Products is one of the world's largest manufacturers of windscreen wipers. Bosch has the world's biggest windscreen wiper factory in Tienen, Belgium, which produces 350,000 wiper blades every day. The first automatic electric wiper arms were patented in 1917 by Charlotte Bridgwood.

Inventor William M. Folberth and his brother, Fred, applied for a patent for an automatic windscreen wiper apparatus in 1919, which was granted in 1921. It was the first automatic mechanism to be developed by an American, but the original invention is attributed by others to Hawaiian, Ormand Wall. Trico later settled a patent dispute with Folberth and purchased Folberth's Cleveland company, the Folberth Auto Specialty Co. The new vacuum-powered system quickly became standard equipment on automobiles, and the vacuum principle was in use until about 1960. In the late 1950s, a feature common on modern vehicles first appeared, operating the wipers automatically for two or three passes when the windscreen washer button was pressed, making it unnecessary to manually turn the wipers on as well. Today, an electronic timer is used, but originally a small vacuum cylinder mechanically linked to a switch provided the delay as the vacuum leaked off.

Intermittent wipers

The inventor of intermittent wipers (non-continuous, now including variable-rate wipers) might have been Raymond Anderson, who, in 1923, proposed an electro-mechanical design. (US Patent 1,588,399). In 1958, Oishei et al. filed a patent application describing not only electro-mechanical, but also thermal and hydraulic designs. (US Patent 2,987,747). Then, in 1961, John Amos, an engineer for the UK automotive engineering company Lucas Industries, filed the first patent application in the UK for a solid-state electronic design. (US patent 3,262,042).

In 1963, another form of intermittent wiper was invented by Robert Kearns, an engineering professor at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan. (United States Patent 3,351,836 – 1964 filing date). Kearns's design was intended to mimic the function of the human eye, which blinks only once every few seconds. In 1963, Kearns built his first intermittent wiper system using off-the-shelf electronic components. The interval between wipes was determined by the rate of current flow into a capacitor; when the charge in the capacitor reached a certain voltage, the capacitor would be discharged, activating one cycle of the wiper motor, and then repeating the process. Kearns showed his wiper design to the Ford Motor Company and proposed that they manufacture the design. Ford executives rejected Kearns' proposal at the time, but later offered a similar design as an option on the company's Mercury line, beginning with the 1969 models. Kearns sued Ford in a multi-year patent dispute that Kearns eventually won in court, inspiring the 2008 feature film Flash of Genius based on a 1993 New Yorker article that covered the legal battle.

In March 1970, French automotive manufacturer Citroën introduced more advanced rain-sensitive intermittent windscreen wipers on its SM model. When the intermittent function was selected, the wiper would make one sweep. If the windscreen was relatively dry, the wiper motor drew high current, which would set the control circuit timer to a long delay for the next wipe. If the motor drew little current, it indicated that the glass was still wet, and would set the timer to minimize the delay.

Power

Wipers may be powered by a variety of means, although most in use today are powered by an electric motor through a series of mechanical components, typically two 4-bar linkages in series or parallel.

Vehicles with air-operated brakes sometimes use pneumatic wipers, powered by tapping a small amount of pressurized air from the brake system to a small air operated motor mounted on or just above the windscreen. These wipers are activated by opening a valve which allows pressurized air to enter the motor.

Early wipers were often driven by a vacuum motor powered by manifold vacuum. This had the drawback that manifold vacuum varies depending on throttle position, and is almost non-existent under wide-open throttle, when the wipers would slow down or even stop. That problem was overcome somewhat by using a combined fuel/vacuum booster pump.

Some cars, mostly from the 1960s and 1970s, had variable-speed, hydraulically-driven wipers, most notably the '61–'69 Lincoln Continental, '69–'71 Lincoln Continental Mark III (but not all '70 models), and '63–'71 Ford Thunderbird. These were powered by the same hydraulic pump also used for the power steering mechanism.

On the earlier Citroën 2CV, the windscreen wipers were powered by a purely mechanical system, a cable connected to the transmission; to reduce cost, this cable also powered the speedometer. The wipers' speed was therefore variable with car speed. When the car was stationary, the wipers were not powered, but a handle under the speedometer allowed the driver to power them by hand.

Shape

Most early wipers used a rubber blade attached to a flat metal base. But as aerodynamic and styling concerns introduced curved windshields, these proved insufficient. In 1945, John W. Anderson, founder of Trico rival Anco, filed a patent for a wiper with branched arms to keep the blade pressed uniformly against both curved and flat glass, adaptable to almost any windscreen curvature. As curved windshields became more popular and widespread, following the debut of the 1947 Studebaker Starlight Coupe, these soon became standard equipment. While they have been superseded by "beam-type" wipers with bodies made of flexible material, this type still remains the most popular.

Wiper blades are made of natural rubber, EPDM rubber (or ethylene propylene rubber) or a combination of both, as natural rubber performs better in cold weather but EPDM rubber doesn't "set" and resists better to thermal aging, UV, ozone and tearing. Some manufacturers coat them with graphite.

Geometry

Most wipers are of the pivot (or radial) type: they are attached to a single arm, which in turn is attached to the motor. These are commonly found on many cars, trucks, trains, boats, airplanes, etc.

Modern windscreen wipers usually move in parallel (Fig. 1, below). However, various Mercedes-Benz models and other cars such as the Volkswagen Sharan employ wipers configured to move in opposite directions (Fig. 2), which is mechanically more complex but can avoid leaving a large unwiped corner of the windscreen in front of the front-seat passenger. A cost benefit to the auto-maker occurs when wipers configured to move in opposite directions do not need to be repositioned for cars exported to right hand drive countries such as the UK and Japan.

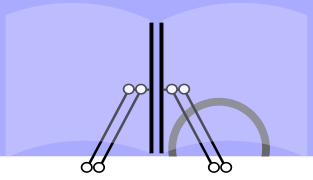

Another wiper design (Fig. 6) is pantograph-based, used on many commercial vehicles, especially buses with large windscreens. Pantograph wipers feature two arms for each blade, with the blade assembly itself supported on a horizontal bar connecting the two arms. One of the arms is attached to the motor, while the other is on an idle pivot. The pantograph mechanism, while being more complex, allows the blade to cover more of the windscreen on each wipe. However, it also usually requires the wiper to be "parked" in the middle of the windscreen, where it may partially obstruct the driver's view when not in use. A few models of automobile sometimes employ a pantograph arm on the driver's side and a normal arm for the passenger. The Triumph Stag, Lexus and several US makes employ this method to cover more glass area where the windscreen is quite wide but also very shallow. The reduced height of the windscreen would need the use of short wiper arms which would not have the reach to the edge of the windscreen.

A simple single-blade setup with a center pivot (Fig. 4) is commonly used on rear windscreens, as well as on the front of some cars. Mercedes-Benz pioneered a system (Fig. 5) called the "Monoblade", based on cantilevers, in which a single arm extends outward to reach the top corners of the windscreen, and pulls in at the ends and middle of the stroke, sweeping out a somewhat M-shaped path. This way, a single blade is able to cover more of the windscreen, displacing any residual streaks away from the centre of the windscreen.

Some larger cars in the late '70s and early '80s, especially LH driver American cars, had a pantograph wiper on the driver's side, with a conventional pivot on the passenger side. Asymmetric wiper arrangements are usually configured to clear more windscreen area on the driver's side, and so are mostly mirrored for left and right-hand-drive vehicles (for example, Fig. 1 vs. Fig 10). One exception is found on the second generations of the Renault Clio, Twingo and Scénic as well as BMW's E60 5 Series and E63 6 Series, the Peugeot 206 and the Nissan Almera Tino, where the wipers always sweep towards the left. On right-hand-drive models, a linkage allows the right-hand wiper to move outwards towards the corner of the windscreen and clear more area.

-

Fig. 1: Most common geometry, found on vast majority of vehicles, mainly LHD cars; RHD Mercedes-Benz W140 and some earlier British cars

Fig. 1: Most common geometry, found on vast majority of vehicles, mainly LHD cars; RHD Mercedes-Benz W140 and some earlier British cars

-

Fig. 2: Widely used alternative configuration suiting either LHD or RHD operation

Fig. 2: Widely used alternative configuration suiting either LHD or RHD operation

-

Fig. 3: SEAT Altea, SEAT León II, SEAT Toledo III

Fig. 3: SEAT Altea, SEAT León II, SEAT Toledo III

-

Fig. 4: Simple-arc single-blade system, used on the VAZ-1111 Oka, Fiat Panda I/SEAT Marbella, Fiat Uno, Citroën AX, Citroën BX, Citroën ZX, SEAT Ibiza I and 1986-2003 Jaguar XJs

Fig. 4: Simple-arc single-blade system, used on the VAZ-1111 Oka, Fiat Panda I/SEAT Marbella, Fiat Uno, Citroën AX, Citroën BX, Citroën ZX, SEAT Ibiza I and 1986-2003 Jaguar XJs

-

Fig. 5: Complex- or eccentric-arc system, used on the Subaru XT as well as the Mercedes-Benz W124, R129, W201, W202, C208 and W210; eccentric design used for passenger wiper on most late-model Mercedes-Benzes

Fig. 5: Complex- or eccentric-arc system, used on the Subaru XT as well as the Mercedes-Benz W124, R129, W201, W202, C208 and W210; eccentric design used for passenger wiper on most late-model Mercedes-Benzes

-

Fig. 6: Pantograph system, used on some buses (e.g. Mercedes-Benz O305), some school buses, some trolleybuses (e.g. Ikarus 415T and ZiU-9) and the Kenworth T600 as well as the rear wiper for the Honda CR-X Si and the Porsche 928 and for the driver's side of the Triumph TR7

Fig. 6: Pantograph system, used on some buses (e.g. Mercedes-Benz O305), some school buses, some trolleybuses (e.g. Ikarus 415T and ZiU-9) and the Kenworth T600 as well as the rear wiper for the Honda CR-X Si and the Porsche 928 and for the driver's side of the Triumph TR7

-

Fig. 7: MAN, DAF XF, Hino 700, Toyota FJ Cruiser, Jaguar E-Type, MGB, MG Midget, Austin Healey Sprite, GMC Hummer EV (a 1968 US-only ruling required a certain percentage of the windscreen to be wiped)

Fig. 7: MAN, DAF XF, Hino 700, Toyota FJ Cruiser, Jaguar E-Type, MGB, MG Midget, Austin Healey Sprite, GMC Hummer EV (a 1968 US-only ruling required a certain percentage of the windscreen to be wiped)

-

Fig. 8: Obsolete design, found on some older fire trucks, utility vehicles and military vehicles, (e.g. ZIL-131, some school buses; same design on single windscreen for Jeep Wrangler YJ

Fig. 8: Obsolete design, found on some older fire trucks, utility vehicles and military vehicles, (e.g. ZIL-131, some school buses; same design on single windscreen for Jeep Wrangler YJ

-

Fig. 9: US military wheeled vehicles, jeepneys, some school buses and utility vehicles, Hummer H1 and HUMVEE

Fig. 9: US military wheeled vehicles, jeepneys, some school buses and utility vehicles, Hummer H1 and HUMVEE

-

Fig. 10: Like Fig. 1 but mirror-reversed, mainly seen on RHD cars, LHD Mercedes-Benz W140, Mercedes-Benz R107/C107

Fig. 10: Like Fig. 1 but mirror-reversed, mainly seen on RHD cars, LHD Mercedes-Benz W140, Mercedes-Benz R107/C107

Other wiper geometries

- Works similar to Fig. 8 but not a split screen windscreen and rest state is at the bottom of the windscreen facing outwards.

- Works similar to Fig. 2 but one wiper has its resting position up and the other down.

- Works similar to Fig. 9, but uses a single wiper.

- Works similar to Fig. 6, but uses only one wiper.

Unusual wiper geometries

- Works as would Fig. 1, but uses a large, single pantograph wiper.

- Works as would Fig. 6, but the wipers are arranged upside down.

- Renault PR100 and its articulated Renault PR180 version

- British Rail Class 92

- Works as would Fig. 1 or Fig. 10, but the wipers are arranged upside down.

Other automotive applications

Rear wipers

Single rear wiper on a Mitsubishi Outlander

Single rear wiper on a Mitsubishi Outlander Double rear wipers on a Toyota Camry (XV10) station wagon

Double rear wipers on a Toyota Camry (XV10) station wagon

Some vehicles are fitted with wipers (with or without washers) on the back window as well. Rear-window wipers are typically found on hatchbacks, station wagons / estates, sport utility vehicles, minivans, and other vehicles with more vertically-oriented rear windows that tend to accumulate dust. First offered in the 1940s, they achieved widespread popularity in the 1970s after their introduction on the Porsche 911 in 1966 and the Volvo 145 in 1969.

Headlight wipers

In the 1960s, as interest in auto safety grew, engineers began researching various headlamp cleaning systems. In late 1968, Chevrolet introduced high pressure fluid headlamp washers on a variety of their 1969 models. In 1970, Saab Automobile introduced headlight wipers across their product range. These operated on a horizontal reciprocating mechanism, with a single motor. They were later superseded by a radial spindle action wiper mechanism, with individual motors on each headlamp. In 1972, headlamp cleaning systems became mandatory in Sweden.

Headlamp wipers have all but disappeared today with most modern designs relying solely on pressurized fluid spray to clean the headlights. This reduces manufacturing cost, minimizes aerodynamic drag, and complies with EU regulations limiting headlamp wiper use to glass-lensed units only (the majority of lenses today are made of plastic.)

Other features

Windscreen washer

See also: Windscreen washer fluidMost windscreen wipers operate together with a windscreen washer; a pump that supplies a mixture of water, alcohol, and detergent (a blend called windscreen washer fluid) from a tank to the windscreen. The fluid is dispensed through small nozzles mounted on the hood. Conventional nozzles are usually used, but some designs use a fluidic oscillator to disperse the fluid more effectively.

In warmer climates, water may also work, but it can freeze in colder climates, damaging the pump. Although automobile antifreeze is chemically similar to windscreen wiper fluid, it should not be used because it can damage paint. The earliest documented idea for having a windscreen wiper unit hooked up to a windscreen washer fluid reservoir was in 1931, Richland Auto Parts Co, Mansfield, Ohio. Uruguayan racecar driver and mechanic Héctor Suppici Sedes developed a windscreen washer in the late 1930s.

Since 2012, nozzles are replaced on some cars (Tesla, Volvo XC60 2018-2021, Citroen C4 Cactus) by a system called AquaBlade, developed by the company Valeo. This system supplies the washing liquid directly from the spoiler element of the wiper blade. This system suppresses visual disturbances during driving and so reduces the reaction time of the driver in case of incident.

Hidden wipers

Some larger cars are equipped with hidden wipers (or depressed-park wipers). When wipers are switched off in standard non-hidden designs, a "parking" mechanism or circuit moves the wipers to the lower extreme of the wiped area near the bottom of the windscreen, but still in sight. For designs that hide the wipers, the windscreen extends below the rear edge of the bonnet. The wipers park themselves below the wiping range at the bottom of the windscreen, but out of sight. Late model vehicles that hide wiper blades under the windscreen need to be placed in a service position in order to lift the wiper blade from the windscreen using the wiper service position.

Rain-sensing wipers

Some vehicles are now available with automatic or driver-programmable windscreen wipers that detect the presence and amount of rain using a rain sensor. The sensor automatically adjusts the speed and frequency of the blades according to the amount of rain detected. These controls usually have a manual override.

Rain-sensing windscreen wipers appeared on various models in the late 20th century, one of the first being the Citroën SM. As of early 2006, rain-sensing wipers are optional or standard on all Cadillacs and most Volkswagens, and are available on many other mainstream manufacturers.

The rain-sensing wipers system currently employed by most car manufacturers today was originally invented and patented in 1978 by Australian, Raymond J. Noack, see U.S. Patents 4,355,271 and 5,796,106. The original system automatically operated the wipers, lights and windscreen washers.

Bladeless alternatives

A common alternative design used on ships, called a clear view screen, avoids the use of rubber wiper blades. A round portion of the windscreen has two layers, the outer one of which is spun at high speed to shed water.

High speed aircraft may use bleed air which uses compressed air from the turbine engine to remove water, rather than mechanical wipers, to save weight and drag. Effectiveness of this method also depends on water-repellent glass treatments similar to Rain-X.

Legislation

Many jurisdictions have legal requirements that vehicles be equipped with windscreen wipers. Windscreen wipers may be a required safety item in auto safety inspections. Some US states have a "wipers on, lights on" rule for cars.

In popular culture

In the 1999 television commercial Synchronicity for the Volkswagen Jetta automobile, windscreen wipers were synchronized with events seen through the car windows, and with the song "Jung at Heart", which was commissioned for the advertising agency Arnold Worldwide and composed by Peter du Charme under the name "Master Cylinder".

See also

Notes

- Buick Verano, Mercedes-Benz W114, W168, W169, W245, W414 and W639, Smart Fortwo (1998-2015), Volkswagen Golf Plus, Volkswagen Sharan I/SEAT Alhambra I, Volkswagen Touran (some models until 2011), Datsun 510 (1968 only), Mitsubishi Delica, Mitsubishi Grandis, Honda Civic (2005–2011), Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme (5th Generation), some minivans, some buses, Peugeot 307, Peugeot 308 (2007-2013), Peugeot 407, Peugeot 508, Peugeot 3008, Peugeot 5008, Peugeot RCZ, Ford Focus (third generation), Ford Mondeo (fourth generation), Ford B-Max, Ford C-Max (second generation), Ford S-Max, Ford Galaxy, Ford Kuga (second generation), Ford Transit Connect (second generation), Ford Transit Custom, Citroën C4, Citroën Xsara Picasso, Citroën C4 Picasso, Citroën C5 II, Citroën C6, Citroën C8/Fiat Ulysse II/Lancia Phedra/Peugeot 807, DS 4, DS 5, BMW i3, BMW i8, Opel Meriva, Opel Zafira, Opel Astra J, Opel Cascada, Chevrolet Volt/Opel Ampera, Renault Scénic III, Renault Espace (2002–present), Renault Vel Satis, Plymouth Voyager/Dodge Caravan/Chrysler Voyager/Chrysler Town & Country, Mazda MPV, some first generation Toyota Previas, third generation Kia Carens

References

- "WINDOW CLEAN". google.com. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Day T (2000). A Century of Recorded Music: Listening to Musical History. Yale University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-300-09401-5.

- ^ "The Windshield Wiper". American Heritage. Archived from the original on 2007-09-11. Retrieved 2010-12-23.

- "Windshield Wipers". Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- "Mary Anderson". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Archived from the original on 2014-03-13. Retrieved 2010-12-20.

- "Window-Cleaning Device". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Archived from the original on December 20, 2011.

- "Locomotive-cab-window cleaner". google.com. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Espacenet – Bibliographic data

- Robert Bosch GmbH (2009-01-16). "BoschLive". Bosch.com.au. Archived from the original on 2011-09-11. Retrieved 2011-09-23.

- "The Evolution of Wind Shield Wipers - A Patent History - IPWatchdog.com | Patents & Patent Law". IPWatchdog.com | Patents & Patent Law. 2014-11-09. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- ^ "Automatic Windshield Wipers - Ohio History Central". www.ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- Schudel, Matt (26 February 2005). "Accomplished, Frustrated Inventor Dies". Washington Post. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "The Cars of James Bond: Lincoln Continental". wordpress.com. 25 June 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "Automotive Mileposts, 1969-1971 Lincoln Continental Mark III". Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Automotive Mileposts, 1955-1979 Ford Thunderbird". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Windshield Wipers 101". Top Gear Philippines.

- "Windshield wiper blade linkage assembly".

- "Tech 101: What you need to know about windshield wipers". hemmings.com.

- 20150047142, Gotzen, Nicolaas, "Epdm Wiper Rubber", issued 2015-02-19

- ^ "The science and ingenuity behind the humble wiper blade". www.imeche.org. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- "The Rear Wiper: A Vital Strand of Porsche DNA". wordpress.com. 30 April 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Windshield Freed Of Snow With Alcohol Wiper", February 1931, Popular Mechanics article bottom half of page

- "car detailing services".

- Supicci Sedes, un espíritu creador - La Voz del Interior, 1 January 2001

- ATZ, Automobiltechnische Zeitschrift, June 2015

- "AAA Digest of Motor Laws: Headlight Use: United States Canada". drivinglaws.aaa.com. American Automobile Association. Archived from the original on 24 June 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Tuoti, Gerry (7 April 2015). "New state law: Wipers on, lights on". Cape Cod Times. Hyannis, Massachusetts. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Warner, Judy (January 11, 1999). "VW Unveils 'Da Da Da'-Like Jetta Spot". Adweek. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Kattleman, Terry (February 1, 2003). "Sound & Vision: Music: The Latest Drive-Time Hit from VW Follows in a Winning Indie Tradition". Ad Age. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- du Charme, Peter. "Jung at Heart by Peter du Charme". Bandcamp. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

External links

| Automotive design | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of a series of articles on cars | |||||||||||||

| Body |

| ||||||||||||

| Exterior equipment |

| ||||||||||||