The women's suffrage movement in Montana started while it was still a territory. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was an early organizer that supported suffrage in the state, arriving in 1883. Women were given the right to vote in school board elections and on tax issues in 1887. When the state constitutional convention was held in 1889, Clara McAdow and Perry McAdow invited suffragist Henry Blackwell to speak to the delegates about equal women's suffrage. While that proposition did not pass, women retained their right to vote in school and tax elections as Montana became a state. In 1895, National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) came to Montana to organize local groups. Montana suffragists held a convention and created the Montana Woman's Suffrage Association (MWSA). Suffragists continued to organize, hold conventions and lobby the Montana Legislature for women's suffrage through the end of the nineteenth century. In the early twentieth century, Jeannette Rankin became a driving force around the women's suffrage movement in Montana. By January 1913, a women's suffrage bill had passed the Montana Legislature and went out as a referendum. Suffragists launched an all-out campaign leading up to the vote. They traveled throughout Montana giving speeches and holding rallies. They sent out thousands of letters and printed thousands of pamphlets and journals to hand out. Suffragists set up booths at the Montana State Fair and they held parades. Finally, after a somewhat contested election on November 3, 1914, the suffragists won the vote. Montana became one of eleven states with equal suffrage for most women. When the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, Montana ratified it on August 2, 1919. It wasn't until 1924 with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act that Native American women gained the right to vote.

Early efforts

The earliest suffrage organizing in the territory of Montana started with the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Frances Willard came to Montana in 1883 in order to set up local WCTU chapters. Willard gave one of the first women's suffrage speeches in the state that year and advised the local chapters to create suffrage committees. The next year, during the state constitutional convention in 1884, equal suffrage for women was proposed by Judge. W. J. Stephens from Missoula. However, neither the suffrage proposal nor statehood was accepted that year.

In 1887, Clara McAdow requested help organizing suffrage groups in Montana from suffragists in the east, but was not able to get a commitment. That same year, women gained the right to vote in school board elections. Women were also allowed to vote on tax issues. However, the vote did not completely extend to Native American women, who were excluded if they lived on a reservation.

During the 1889 state Constitutional Convention, Clara's husband, Perry McAdow from Fergus County, proposed adding women's suffrage language. He invited Henry Blackwell to the convention as a speaker. Blackwell said, writing to Lucy Stone, "There has never been a woman suffrage meeting held in Montana." He said that suffragists should have come to Montana when Clara McAdow wrote them for help earlier. Blackwell lobbied as many convention delegates as he was able. He spoke to the convention and begged that at the very least delegates did not remove any suffrage women were already entitled to in Montana. Blackwell was able to persuade the constitutional delegates to consider adding language to the state constitution that would make later changes to suffrage easier. However, even that proposal failed, though women retained their right to vote in school board elections as Montana became a state.

In Helena, a women's suffrage club was founded in January 1890. However, by 1895, the club had dissolved. On May 15, 1895, Emma Smith DeVoe from the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) came to Montana where she organized chapters in several cities. The NAWSA chapters worked to create a state suffrage convention in Helena which was held September 2 and 3 in 1895. Carrie Chapman Catt attended as a speaker. The creation of the Montana Woman's Suffrage Association (MWSA) came out of the convention and Harriet P. Sanders accepted the role as first president. Catt provided the local groups with a course of study on women's suffrage tactics and issues.

A women's suffrage amendment bill was introduced in the state congress in 1895 by Representative John S. Huseby. It passed by the necessary two-thirds vote in the House. T. W. Brosnan from Cascade County presented two petitions for women's suffrage to the Senate. The bill was unable to pass the Senate, despite the petitions.

In 1896, DeVoe came back to Montana to continue organizing suffragists. That year, on November 17 to 19, MWSA held their state convention at Butte. It was a large convention and MWSA appointed a central committee made up of women from around the state. Ella Knowles Haskell became the group's next president. Haskell was an effective leader and helped get 2,500 signatures on a petition for a women's suffrage amendment to the 1887 state legislature. Some of the signers also came to lobby politicians. MWSA set up a legislative committee which included women from almost every county in Montana to lobby the legislators. During deliberations in the legislature, suffragists "overflowed the galleries and filled available space on the floor." Haskell was asked to speak to the legislature and later, the legislature asked to hear Sarepta Sanders. Despite the suffragists' efforts, the bill for the amendment did not get the required two-thirds vote to pass.

The 1897 MWSA convention was held in Helena in November. By this year, there were 35 local suffrage groups in Montana. At this convention, the suffragists also formed an Equal Suffrage Party which was organized like other political parties in the state. In 1898, suffragists solicited the positions of legislative candidates on women's suffrage. MWSA held another convention in October 1899 and elected Maria M. Dean as president. Catt and Mary Garrett Hay came to the convention to campaign. Also in 1899, Mary B. Atwater helped to lobby the Montana Legislature for another women's suffrage amendment. John R. Toole introduced the amendment during this session and several suffragists again testified for women's suffrage. The bill was defeated again.

Helena suffragists lobbied at the Republican, Democratic and Populist party conventions for a women's suffrage plank in 1900. At this time, the only active local club in Montana was the Helena Equal Suffrage Club. Catt, Gail Laughlin and Laura A. Gregg returned to Montana and helped reorganize the women's suffrage club in Helena in 1902. Laughlin spent that summer organizing women's suffrage groups around the state. In November she came to Great Falls to give a speech and the Great Falls Tribune called her "well worth hearing." In 1903, a women's suffrage amendment was introduced in the state legislature, but didn't pass.

The women's suffrage movement in Montana had stalled by 1905. Even though women's suffrage amendments were proposed in the legislature, suffragists did not actively campaign for them.

Getting the vote

In 1911, the Montana Legislature introduced a new women's suffrage bill. Jeannette Rankin addressed the legislators during the deliberations. When the bill went up for votes, it received a majority of support, but not the two-thirds vote required to pass. However, the majority vote gave suffragists in Montana hope. In 1911 and 1912, women's suffrage groups hosted booths at the Montana State Fair where they passed out literature and buttons.

In January 1913, the Montana Legislature passed another women's suffrage bill. Leading up to the referendum vote in 1914, suffragists staged a publicity campaign and Rankin organized women throughout the state. She set up people to act as a claque during political speeches. This encouraged politicians to mention suffrage more often. Maggie Smith Hathaway traveled 5,700 miles through Montana bringing the message of women's suffrage, earning her the nickname of "The Whirlwind." Members of the WCTU spoke to church members about women's suffrage. In rural areas, suffragists hosted rallies with a dance afterwards. It was reported that "oldtimers" said "What would our State have been without the women? You bet you can count on us." Suffragists even spoke to movie-goers who were waiting for the next film to start.

Suffrage supporters contacted Montana newspapers every week about the vote. They sent out around 100,000 letters and sent personal letters to farmers in the state. Thirty-thousand copies of "Women Teachers of Montana Should Have the Vote" were printed and passed out by the Missoula Teachers' Suffrage Committee. Suffragists starting publishing a newspaper in Helena, the Suffrage Daily News.

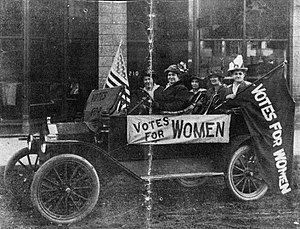

In the spring, Harriet Burton Laidlaw and James Lees Laidlaw visited Montana. James Laidlaw and Wellington D. Rankin founded a Montana chapter of the National Men's Suffrage League. Suffragists persuaded the governor, Sam V. Stewart, to declare May 2 "Women's Day." On that day, they held a car rally on Last Chance Gulch in Helena. In June, Rankin gave a speech to the Montana Federation of Women's Clubs (MFWC) in Lewistown, Montana. The speech was covered by Belle Fligelman Winestine.

At the Montana State Fair in September, suffragists sponsored a women's suffrage booth. At the booth, they gave out copies of the Suffrage Daily News. Children attending the fair were given hat bands that read "I want my mother to vote." After the fair, a large parade was held in Helena. Cars were decorated with suffrage colors and delegates represented different areas of Montana. Anna Howard Shaw and Rankin lead the parade. The Boy Scouts and the Anaconda band also marched in the parade. Hundreds of women marched wearing yellow outfits and thousands of spectators came to view the parade which stretched out over a mile.

The campaign leading up to the vote cost around $8,000 and that was with many of the women donating their time and working for free. When the suffragists' funds were lost when a bank collapsed, James Laidlaw gave funds to the suffrage effort. Rosalie Jones donated $1,000. Suffragists raised money by denying themselves entertainment, such as the movies, and donated that money to the cause instead. Money was also raised through society teas and theater presentations.

The vote was held on November 3, 1914. Poll watchers were on hand during the election because suffragists worried that the anti-suffragists might try to cheat. The tight race was counted over several days with areas of the state refusing to report the count of their ballot boxes. Anaconda officials locked up their election reports and would not provide them, holding up the tallies. Rankin threatened to hire lawyers to ensure a full count and let NAWSA know about the situation. Lawyers were hired and the press was notified. Edith Clinch took control of the situation in Anaconda and in Boulder, Montana, Mary Atwater was in charge of watching the count. Finally all ballots were tallied. The amendment passed by 41,302 to 37,588. Montana became one of eleven states to pass equal women's suffrage.

In January 1915, Rankin invited suffragists and groups to Helena for a conference on "intelligent use of the ballot." Suffrage groups in the state changed their names to Good Government Clubs and worked towards positive political change. These later became Montana League of Women Voters groups.

On July 29, 1919, Governor Samuel Stewart recalled Montana legislators to open a special session. During the session, Stewart urged legislators to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment because "Montana already has woman suffrage; her women vote upon every important issue presented to our people." The ratification passed immediately and the governor signed it on August 2, 1919. Montana was the thirteenth state to ratify the amendment. Native Americans in Montana could not vote until 1924 when the Indian Citizenship Act was passed.

Anti-suffragism in Montana

The anti-suffrage movement in Montana consisted of both men and women who did not want things in society to change. Anti-suffragists felt that women's suffrage challenged traditional gender roles. Women were meant to be in charge of domestic spheres and stay out of politics they argued. In addition, antis claimed that women would just vote the same way as the men in their lives did. Anti-suffragists claimed that women didn't really want to vote. Politician, Martin Maginnis, claimed that giving women the vote would be forcing something on women that they really didn't want or need. Legislators passed along stories of women bragging that they had voted more than once in school board elections. Maginnis, believed that giving the vote to women would lead to a theocracy. Conversely, another politician, G. L. Ramsey, called the idea of women voting "unChristian."

Some of the anti-suffragists were also against prohibition. In order to keep the issues separate, the Montana Equal Suffrage Association (MESA) would not allow the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) to march in their parade in 1914. Mining interests, like the Anaconda Co., worried that women getting the vote would mean more safety laws and guidelines in their mines.

Anti-suffrage women did not get organized as quickly as the suffragists because antis believed that becoming involved in politics was "unwomanly." Anti-suffragists did not organize until late in the suffrage fight. In Butte, at the end of the summer in 1914, women founded the Montana Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. They held a booth at the Montana State Fair and handed out anti-suffrage literature.

See also

- List of Montana suffragists

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Montana

- Women's suffrage in the United States

References

- ^ Larson 1973, p. 26.

- ^ Ward 1974, p. 14.

- ^ Larson 1973, p. 27.

- Lincoln, Marga (13 August 2020). "Montana suffragists played key role in passing 19th Amendment". Helena Independent Record. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- Foley, Iverson & Lawson 2009, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Baumler et al. 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Wheeler 1981, p. 6.

- Wheeler 1981, pp. 7–8.

- Wheeler 1981, p. 9.

- Ward 1974, p. 17.

- ^ Larson 1973, p. 29.

- ^ Larson 1973, p. 30.

- ^ Larson 1973, p. 31.

- Larson 1973, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Larson 1973, p. 32.

- ^ Anthony 1902, p. 798.

- ^ Ward 1974, p. 45.

- Ward 1974, p. 46.

- ^ Larson 1973, p. 33.

- ^ Anthony 1902, p. 797.

- Ward 1974, p. 53.

- Ward 1974, p. 55.

- ^ Ward 1974, p. 56.

- Ward 1974, p. 58.

- ^ Ward 1974, p. 63.

- Ward 1974, p. 68.

- ^ Ward 1974, p. 70.

- Ward 1974, p. 75.

- Ward 1974, p. 69.

- Anthony 1902, p. 801.

- Ward 1974, p. 77.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 360.

- "Miss Gail Laughlin on Woman Suffrage". Great Falls Tribune. 1902-11-19. p. 8. Retrieved 2020-10-05 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 361.

- ^ Schontzler, Gail (16 March 2014). "Votes for Women". Bozeman Daily Chronicle. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- Ward 1974, p. 112.

- ^ Baumler et al. 2014, p. 5.

- "Equal Suffragists to Organize State". The Billings Gazette. 1914-02-15. p. 3. Retrieved 2020-10-05 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ward 1974, p. 122.

- ^ Schaffer 1964, p. 13.

- ^ Inbody, Kristen (8 November 2014). "Women's suffrage: Montana backers targeted their message to each group they spoke with". Great Falls Tribune. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- Harper 1922, p. 364.

- Harper 1922, p. 365.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 363.

- "The Missoula Teachers' Suffrage". Yellowstone Monitor. 1914-08-13. p. 7. Retrieved 2020-10-05 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Suffrage Daily News (Helena, Mont.) 1914–191?". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- ^ Winestine 1974, p. 71.

- ^ Winestine 1974, p. 73.

- ^ "Livingston News". The Butte Miner. 1914-09-22. p. 9. Retrieved 2020-10-04 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Dr. Anna Shaw is in the City". The Independent-Record. 1914-09-25. p. 4. Retrieved 2020-10-06 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Parade Great Success". The Suffrage Daily News. 26 September 1914. Retrieved 6 October 2020 – via Chronicling America.

- Ward 1974, p. 143.

- Schaffer 1964, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Schaffer 1964, p. 14.

- ^ Ward 1974, p. 144.

- Ward 1974, p. 150.

- Harper 1922, p. 367.

- Ward 1974, p. 151.

- ^ Kohl, Martha (2019-08-02). "Montana History Revealed: Montana and the Nineteenth Amendment". Montana History Revealed. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- ^ Winestine 1974, p. 72.

- Ward 1974, p. 25.

- Schaffer 1964, p. 10.

- Wheeler 1981, p. 12.

- Ward 1974, p. 24.

- Baumler et al. 2014, p. 6.

- Pickett, Mary (2 November 2014). "Jeannette Rankin and the path to women's suffrage in Montana". The Billings Gazette. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- Ward 1974, p. 141.

- ^ Ward 1974, p. 142.

Sources

- Anthony, Susan B. (1902). Anthony, Susan B.; Harper, Ida Husted (eds.). The History of Woman Suffrage. Vol. 4. Indianapolis: The Hollenbeck Press.

- Baumler, Ellen; Ferguson, Laura K.; Foley, Jodie; Hanshew, Annie; Jabour, Anya; Kohl, Martha; Walter, Marcella Sherfy (Summer 2014). "Women's History Matters: The Montana Historical Society's Suffrage Centennial Project". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 64 (2): 3–20, 91–92. JSTOR 24419894.

- Foley, Neil; Iverson, Peter; Lawson, Steven F. (2009). Salvatore, Susan Cianci (ed.). "Civil Rights in America: Racial Voting Rights" (PDF). A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study: 1–155.

- Harper, Ida Husted (1922). The History of Woman Suffrage. New York: J.J. Little & Ives Company.

- Larson, T. A. (Winter 1973). "Montana Women and the Battle for the Ballot". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 23 (1): 24–41. JSTOR 4517748.

- Schaffer, Ronald (January 1964). "The Montana Woman Suffrage Campaign, 1911–194?". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 55 (1): 9–15. JSTOR 40487881.

- Ward, Doris Buck (1974). The Winning of Woman Suffrage in Montana (PDF) (Master of Arts in History thesis). Montana State University.

- Wheeler, Leslie (Summer 1981). "Woman Suffrage's Gray-Bearded Champion Comes to Montana, 1889". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 31 (3): 2–13. JSTOR 4518582.

- Winestine, Belle Fligelman (Summer 1974). "Mother Was Shocked". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 24 (3): 70–79. JSTOR 4517906.