A photograph of Japanese women from the book "Japan And Japanese" (1902) A photograph of Japanese women from the book "Japan And Japanese" (1902) | |

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 5 (2010) |

| Women in parliament | 10.2% (2018) |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 80.0% (2010) |

| Women in labour force | 64.6% employment rate (2015) |

| Gender Inequality Index | |

| Value | 0.083 (2021) |

| Rank | 22nd out of 191 |

| Global Gender Gap Index | |

| Value | 0.66 (2024) |

| Rank | 118th out of 146 |

Women in Japan were recognized as having equal legal rights to men after World War II. Japanese women first gained the right to vote in 1880, but this was a temporary event limited to certain municipalities, and it was not until 1945 that women gained the right to vote on a permanent, nationwide basis.

Modern policy initiatives in Japan have aimed to promote both motherhood and women's participation in the workforce, but these efforts have yielded mixed results. Traditional gender expectations, especially for married women and mothers, still shape societal norms and create barriers to economic equality. While the gender income gap has gradually narrowed, it persists, with women earning less than men, particularly in leadership and high-paying roles. Factors such as occupational segregation, the concentration of women in part-time or non-regular jobs, and limited career advancement contribute to this gap.

In 2020, the high school enrollment rate of Japanese women will be 95%, the same as that of Japanese men, and the combined enrollment rate for universities, colleges, and junior colleges will be 58%, 1% higher than that of men. Despite higher educational attainment, societal expectations around caregiving still impact women's career progression and work-life balance. As a result, while academic progress is evident, significant gender inequality remains in various aspects of Japanese society.

The life expectancy of Japanese women is 87.14 years, the longest among women in any country, 6 years longer than that of Japanese men, 81.09 years.

In 2023, Japan ranked 23rd out of 177 countries on the Women, Peace and Security Index, which is based on 13 indicators of inclusion, justice, and sacurity. In 2024, Japan ranked 22nd out of 193 countries on the Gender Inequality Index, which measures equality between men and women in sexual and reproductive health, empowerment and economic participation. On the other hand, Japan ranked a low 118th out of 146 countries on the Global Gender Gap Index. Japan was judged to have a small gender gap in education and health, but a large gap in political and economic participation, resulting in a lower ranking.

Transition of social roles

Late 19th/early 20th century depictions of Japanese women, Woman in Red Clothing (1912) and Under the Shade of a Tree (1898) by Kuroda Seiki. Japanese Woman (1903) by Hungarian artist Bertalan Székely.

Late 19th/early 20th century depictions of Japanese women, Woman in Red Clothing (1912) and Under the Shade of a Tree (1898) by Kuroda Seiki. Japanese Woman (1903) by Hungarian artist Bertalan Székely.

The extent to which women could participate in Japanese society has varied over time and social classes. In the 8th century, Japan had an empress, and in the 12th century during the Heian period, women in Japan could inherit property in their own names and manage it by themselves: "Women could own property, be educated, and were allowed, if discrete (sic), to take lovers."

Countess Mutsu Ryōko, wife of notable diplomat Count Mutsu Munemitsu. Photographed in 1888.

Countess Mutsu Ryōko, wife of notable diplomat Count Mutsu Munemitsu. Photographed in 1888. Yanagiwara Byakuren, a poet and member of the imperial family

Yanagiwara Byakuren, a poet and member of the imperial family

From the late Edo period, the status of women declined. In the 17th century, the "Onna Daigaku", or "Learning for Women", by Confucianist author Kaibara Ekken, spelled out expectations for Japanese women, stating that "such is the stupidity of her character that it is incumbent on her, in every particular, to distrust herself and to obey her husband".

During the Meiji period, industrialization and urbanization reduced the authority of fathers and husbands, but at the same time the Meiji Civil Code of 1898 (specifically the introduction of the "ie" system) denied women legal rights and subjugated them to the will of household heads.

Behavioral expectations

In interviews with Japanese housewives in 1985, researchers found that socialized feminine behavior in Japan followed several patterns of modesty, tidiness, courtesy, compliance, and self-reliance. Modesty extended to the effective use of silence in both daily conversations and activities. Tidiness included personal appearance and a clean home. Courtesy, another trait, was called upon from women in domestic roles and in entertaining guests, extended to activities such as preparing and serving tea.

Lebra's traits for internal comportment of femininity included compliance; for example, children were expected not to refuse their parents. Self-reliance of women was encouraged because needy women were seen as a burden on others. In these interviews with Japanese families, Lebra found that girls were assigned helping tasks while boys were more inclined to be left to schoolwork. Lebra's work has been critiqued for focusing specifically on a single economic segment of Japanese women.

Although Japan remains a socially conservative society, with relatively pronounced gender roles, Japanese women and Japanese society are quite different from the strong stereotypes that exist in foreign media or travel guides, which paint the women in Japan as 'submissive' and devoid of any self-determination. Another strong stereotype about Japan is that women always stay in the home as housewives and that they do not participate in public life: in reality most women are employed – the employment rate of women (age 15–64) is 69.6% (data from OECD 2018).

Political status of women

In 1880, women were given the right to vote for the first time in Japan, albeit on a limited basis. On April 8, 1880, an act was passed establishing councils of publicly elected representatives in wards (区), towns (町), and villages (村), and allowing each municipality to establish its own election rules. As a result, Kamimachi and Kosakadaka Village in Kochi Prefecture gave female householders the right to vote in addition to male, marking the first time that women exercised the right to vote in Japan. However, on May 7, 1884, this law was amended and the right to vote was restricted to men over the age of 20 nationwide. Women were given the right to vote nationwide in December 1945, after World War II, when the election law for the House of Representatives was amended.

As the new de facto ruler of Japan, Douglas MacArthur ordered the drafting of a new constitution for Japan in February 1946. Four women were in the working group, including Beate Sirota Gordon who was enlisted to the subcommittee assigned to writing the section of the constitution devoted to civil rights and women's rights in Japan. This allowed them greater freedom, equality to men, and a higher status within Japanese society.

In 1960, Masa Nakayama was appointed Minister of Health and Welfare, becoming the first female Minister of State. As a member of the House of Councillors, Chikage Oogi held several important government positions, including Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. She was the first woman to be awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun in 2003, the first woman to be appointed President of the House of Councillors in 2004, and the first woman to be awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers in 2010.

Female representation in politics

In 1994, Japan implemented electoral reform and introduced a mixed electoral system that included both single-member districts (SMD) using plurality and a party list system with proportional representation. In general, the proportion of female legislators in the House of Representatives has grown since the reform. However, when it comes to women's representation in politics, Japan remains behind other developed democracies as well as many developing countries. As of 2019, Japan ranks 164th out of 193 countries when it comes to the percentage of women in the lower or single house. In the 2021 Japanese general election, less than 18 percent of candidates (186 out of 1051) for the House of Representatives were women. Of these 186 candidates, 45 were elected, constituting 9.7 percent of the 465 seats in the lower chamber. This number represents a decline from the 2017 general election, which resulted in women winning 10.1 percent of House seats. The decrease in women's representation has taken place although the Japanese government has expressed a will to address this inequality of numbers in the 21st century of the Heisei period through several focused initiatives, and a 2012 poll by the Cabinet Office found that nearly 70% of all Japanese polled agreed that men were given preferential treatment.

Japanese women fare better when it comes to local politics. As of 2015, women made up 27.8% of the local assemblies in the Tokyo's Special Wards, 17.4% in designated cities, 16.1% in general cities, 10.4% in towns and villages, and 9.1% in prefectures. In 2019, the proportion of female candidates in local assembly elections hit a record high of 17.3% in city assembly elections and 12.1% in town and village assembly elections. Similar to that in national politics, women's representation in Japan's local politics has seen a general upward trend since the 20th century, but still lags behind other developed countries.

In the 2022 Japanese House of Councillors election a record 35 women were elected to Japan's House of Councillors, the country's upper house. The number of women candidates at the election also reached a record high of 181.

The LDP and female representation

The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has made promises to increase the presence of women in Japanese politics, but has not achieved their stated goals. For example, in 2003, the LDP expressed commitment to achieving 30% female representation in political and administrative positions by 2020 per international norms. However, they remain far from this number. Scholars have noted that the internal structure and rules of the LDP do not favor female candidates. The LDP often seeks out candidates with experience in bureaucracy or local politics, which disadvantages women since they are less likely to have been in these positions. The LDP also has a bottom-up nomination process, whereby the initial nominations are made by local party offices. As these local offices are dominated by men, or the old boys' network, it is difficult for Japanese women to be nominated by the LDP. A break from this bottom-up process took place in 2005, when Prime Minister and President of the LDP Junichiro Koizumi himself placed women at the top of the PR lists. As a result, all of the 26 LDP's women candidates won either by plurality in their SMD or from the PR list. However, Koizumi's top-down nomination was not a reflection of the LDP's prioritization of gender equality, but rather a political strategy to draw in votes by signaling change. After this election, the LDP has returned to its bottom-up nomination process.

Opposition parties and female representation

In 1989, the Japan Socialist Party (JSP), the largest left-wing opposition party to the LDP at the time, succeeded in electing 22 women to the Diet. The record number of women elected to the Diet was dubbed the "Madonna Boom." Under the leadership of Takako Doi, the JSP ran women outside of conventional political circles and emphasized their clean, "outsider" status to juxtapose themselves against the LDP, who were facing accusations of bribery, a sex scandal, and public dismay at its consumption tax policies at the time. As a result, these "Madonnas" were typical housewives with little to no political experience. However, the JSP quickly lost momentum afterwards. In the 1992 House of Councillors election, only 4 women members of the JSP were reelected. The JSP also failed to take advantage of the Madonna Boom to institutionalize gender quotas due to other priorities on its agenda.

Another spike in the number of women in the Japanese Diet came in 2009, when the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) took over the House of Representatives from the LDP in a landslide victory. Out of the 46 female candidates ran by the DPJ, 40 were elected. However, the DPJ also failed to capitalize on this momentum to institutionalize gender quotas. While the DPJ implemented a few non-quota policies with the aim of increasing women's representation, the effects of these policies were only marginal. Similar to the LDP in 2005, the DPJ ran a large number of women candidates not because the party cared about gender equality, but due to political strategy. In fact, the DPJ imitated Prime Minister Koizumi's strategy of indicating reform and societal change through its nomination of women.

Explanations of low female representation

Survey experiments show that Japanese voters do not have a bias against female candidates; rather, the low levels of female representation in Japanese politics is due to Japanese women's reluctance to seek office. Japanese women are less likely to run for office because of socially mandated gender roles, which dictate that women should take care of children and the household. Research suggests that Japanese women are more willing to run for office if parties provide support with household duties during the campaign. Women candidates of reproductive age are also less likely than men to run in SMD in Japan, as opposed to party-list seats, which can be explained by the higher time commitment associated with running in SMD. Furthermore, when Japanese women marry, they often have to leave their home and move in with their husbands. As a result, Japanese women are less able to run for local assemblies because they lack connections with their locality.

The gender roles that discourage Japanese women from seeking elected office have been further consolidated through Japan's model of the welfare state. In particular, since the postwar period, Japan has adopted the "male breadwinner" model, which favors a nuclear-family household in which the husband is the breadwinner for the family while the wife is a dependant. When the wife is not employed, the family is eligible for social insurance services and tax deductions. With this system, the Japanese state can depend on the housewives for care-related work, which reduces state social expenditures. Yet, the "male breadwinner" model has also entrenched gender roles by providing an optimal life course for families that discourage women participating in public life.

Sexism and harassment in politics

Given the dominance of men in Japanese politics, female politicians often face gender-based discrimination and harassment in Japan. They experience harassment from the public, both through social media and in-person interactions, and from their male colleagues. A 2021 survey revealed that 56.7% of 1,247 female local assembly members had been sexually harassed by voters or other politicians. Even though the 1997 revision of the EEOL criminalized sexual harassment in the workplace, female politicians in Japan often do not have the same support when they are harassed by male colleagues. The LDP has been reluctant to implement measures to counter harassment within the party and to promote gender equality more generally. However, vocal female politicians of the party like Seiko Noda have publicly condemned male politicians' sexist statements.

Professional life

In 1947, the Labor Standards Act was enacted, providing for equal pay for equal work, which means that an employee cannot be paid differently than a male employee because she is a woman. In 1986, the Equal Employment Opportunity Law took effect, prohibiting discrimination in aspects like dismissal and retirement. The law was revised in 1997 to be more comprehensive, prohibiting discrimination in recruitment and promotion as well. Another round of revision in 2006 also prohibits job requirements that disproportionately advantage one gender over another, or indirect discrimination. However, women remain economically disadvantaged as a wage gap remains between full-time male and female workers. There also exists a wage gap between full-time and irregular workers despite the rising percentage of irregular workers among women.

During the 21st century, Japanese women are working in higher proportions than the United States's working female population. The earnings gap between men and women in Japan has narrowed over the years: in 1989, women workers earned only 60.2% of men's earnings, but by 2021 the gap had narrowed to 75.2%. For full-time workers only, women earned 77.6% of men's earnings, about 10% below the OECD average, about the same as in Israel, and about 9% higher than in South Korea. At the 2020, the largest source of the gender earnings gap is the difference in job titles, followed by the difference in tenure, and these differences arise because nearly 50% of women leave the workforce to have children and care for them. According to a survey conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in 2023, 10.2% of the 7,780 companies surveyed said they had received complaints from female employees about harassment for taking leave for pregnancy, childbirth or childcare in the past three years.

Japan has a strong tradition of women being housewives after marriage. These include a family wage offered by corporations which subsidized health and housing subsidies, marriage bonuses and additional bonuses for each child; and pensions for wives who earn below certain incomes. When mothers do work, they often pick up part-time, low-paying jobs based on their children's or husband's schedule. Taking care of the family and household is seen as a predominately female role, and working women are expected to fulfill it. The obento box tradition, where mothers prepare elaborate lunches for their children to take to school, is an example of a domestic female role. Nevertheless, in recent years the number of women who work has increased: in 2022, women made up 44.9% of the labour force of Japan. Japan has an especially high proportion of women who work part-time, and a majority of those women are mothers.

A number of government and private post-war policies have contributed to a gendered division of labor. Additionally, in 1961, income for wives of working men were untaxed below $10,000; income above that amount contributed to overall household income. Corporate culture also plays a role; while many men are expected to socialize with their managers after long work days, women may find trouble balancing child-rearing roles with the demands of mandatory after-work social events.

Some economists suggest that a better support system for working mothers, such as a shorter daily work schedule, would allow more women to work, increasing Japan's economic growth. To that end, in 2003, the Japanese government set a goal to have 30% of senior government roles filled by women. In 2015, only 3.5% were; the government has since slashed the 2020 goal to 7%, and set a private industry goal to 15%.

Family life

The traditional role of women in Japan has been defined as "three submissions": young women submit to their fathers, married women submit to their husbands, and elderly women submit to their sons. Strains of this arrangement can be seen in contemporary Japan, where housewives are responsible for cooking, cleaning, and child-rearing and support their husbands so they can work without any worries about the family, as well as balancing the household's finances. Yet, as the number of dual-income households rises, women and men are sharing household chores, and research shows that this has led to increased satisfaction over households that divide labor in traditional ways.

Families, prior to and during the Meiji restoration, relied on a patriarchal lineage of succession, with disobedience to the male head of the household punishable by expulsion from the family unit. Male heads of households with only daughters would adopt male heirs to succeed them, sometimes through arranged marriage to a daughter. Heads of households were responsible for house finances, but could delegate to another family member or retainer (employee). Women in these households were typically subject to arranged marriages at the behest of the household's patriarch, with more than half of all marriages in Japan being preemptively arranged until the 1960s. Married women marked themselves by blackening their teeth and shaving their eyebrows.

After the Meiji period, the head of the household was required to approve of any marriage. Until 1908, it remained legal for husbands to murder wives for infidelity.

As late as the 1930s, arranged marriages continued, and so-called "love matches" were thought to be rare and somewhat scandalous, especially for the husband, who would be thought "effeminate".

The Post-War Constitution, however, codified women's right to choose their partners. Article 24 of Japan's Constitution states:

- Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through mutual cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife as a basis. With regard to choice of spouse, property rights, inheritance, choice of domicile, divorce and other matters pertaining to marriage and the family, laws shall be enacted from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes.

This established several changes to women's roles in the family, such as the right to inherit the family home or land, and the right of women (over the age of 20) to marry without the consent of the house patriarch.

In the early Meiji period, many girls married at age 16; by the post-war period, it had risen to 23, and continued to rise. The average age for a Japanese woman's first marriage has steadily risen since 1970, from 24 to 29.3 years old in 2015.

Right to divorce

In the Tokugawa period, men could divorce their wives simply through stating their intention to do so in a letter. Wives could not legally arrange for a divorce, but options included joining convents, such as at Kamakura, where men were not permitted to go, thus assuring a permanent separation.

Under the Meiji system, however, the law limited grounds for divorce to seven events: sterility, adultery, disobedience to the parents-in-law, loquacity, larceny, jealousy, and disease. However, the law offered a protection for divorcees by guaranteeing a wife could not be sent away if she had nowhere else to go. Furthermore, the law allowed a woman to request a divorce, so long as she was accompanied by a male relative and could prove desertion or imprisonment of the husband, profligacy, or mental or physical illness.

By 1898, cruelty was added to the grounds for a woman to divorce; the law also allowed divorce through mutual agreement of the husband and wife. However, children were assumed to remain with the male head of the household. In contemporary Japan, children are more likely to live with single mothers than single fathers; in 2013, 7.4% of children were living in single-mother households; only 1.3% live with their fathers.

When divorce was granted under equal measures to both sexes under the post-war constitution, divorce rates steadily increased.

In 2015, Article 733 of Japan's Civil Code stating that women could not remarry until six months after divorce was amended to specify 100 days. The six-month ban on remarriage for women previously aimed to "avoid uncertainty regarding the identity of the legally presumed father of any child born in that time period". Under article 772, a child born 300 days after divorce is presumed to be the legal child of the previous husband. In a ruling issued on December 16, 2015, the Supreme Court of Japan stated that, in light of the new law requiring 100 days before women's remarriage, any child born after 200 days of remarriage is to be considered the legal child of the current husband, so there is no confusion over the paternity of a child born to a woman who has remarried.

The Ministry of Japan revealed the outline of an amendment for the Civil Code of Japan on February 18, 2016. This amendment shortens the women's remarriage period to 100 days and allows any woman who is not pregnant during the divorce to remarry immediately after divorce.

Surname change

The Civil Code of Japan requires legally married spouses to have the same surname. Although the law is gender-neutral, meaning that either spouse is allowed to change his/her name to that of the other spouse, Japanese women have traditionally adopted their husband's family name and 96% of women continue to do so as of 2015. In 2015, the Japanese Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the law, noting that women could use their maiden names informally, and stating that it was for the legislature to decide on whether to pass new legislation on separate spousal names.

Motherhood

While women before the Meiji period were often considered incompetent in the raising of children, the Meiji period saw motherhood as the central task of women, and allowed education of women toward this end. In Japanese society, mothers usually place a strong emphasis on their children's education and moral growth, with a special focus on nurturing values like politeness, respect and responsibility. Traditionally and historically women were typically responsible for both parenting and managing household matters within the family structure.

There is continuing debate about the role women's education plays in Japan's declining birthrate. Japan's total fertility rate is 1.4 children born per woman (2015 estimate), which is below the replacement rate of 2.1. Japanese women have their first child at an average age of 30.3 (2012 estimate).

Government policies to increase the birthrate include early education designed to develop citizens into capable parents. Some critics of these policies believe that this emphasis on birth rate is incompatible with a full recognition of women's equality in Japan.

Education

With the development of society, more and more girls are going to colleges to receive higher education. Today, more than half of Japanese women are college or university graduates. The proportion of female researchers in Japan is 14.6%.

Modern education of women began in earnest during the Meiji era's modernization campaign. The first schools for women began during this time, though education topics were highly gendered, with women learning arts of the samurai class, such as tea ceremonies and flower arrangement. The 1871 education code established that students should be educated "without any distinction of class or sex". Nonetheless, after 1891 students were typically segregated after third grade, and many girls did not extend their educations past middle school.

By the end of the Meiji period, there was a women's school in every prefecture in Japan, operated by a mix of government, missionary, and private interests. By 1910, very few universities accepted women. Graduation was not assured, as often women were pulled out of school to marry or to study "practical matters".

Notably, Tsuruko Haraguchi, the first woman in Japan to earn a PhD, did so in the US, as no Meiji-era institution would allow her to receive her doctorate. She and other women who studied abroad and returned to Japan, such as Yoshioka Yayoi and Tsuda Umeko, were among the first wave of women's educators who lead the way to the incorporation of women in Japanese academia.

After 1945, the Allied occupation aimed to enforce equal education between sexes; this included a recommendation in 1946 to provide compulsory co-education until the age of 16. By the end of 1947, nearly all middle schools and more than half of high schools were co-educational.

In 2012, 98.1% of female students and 97.8% of male students were able to reach senior high school. Of those, 55.6% of men and 45.8% of women continued with undergraduate studies, although 10% of these female graduates attended junior college.

Culture

During the Heian period (794-1185), court culture flourished and Japanese women were active as writers. Murasaki Shikibu, who wrote The Tale of Genji, and Sei Shōnagon, who wrote The Pillow Book, are particularly famous. In the Kamakura period (1185-1333), when the samurai class seized power, the patriarchal system was respected and the activities of women writers declined.

It was not until the Meiji era (1868-1912) that women writers became active again. The most prominent women writers of this period were Ichiyō Higuchi and Akiko Yosano, and Higuchi's portrait was used on the 5,000 yen bill. Yosano used female sensuality as the subject of her works and influenced the women's liberation movement in Japan. In 1891, Shimizu Shikin published Koware Yubiwa (The Broken Ring), often called Japan's first feminist novel, and in 1889, Kimura Akebono attracted attention for her portrayal of progressive women in Fujo no Kagami (A Great Example of Women). In 1911, Hiratsuka Raichō published Seitō (Bluestocking), the first literary magazine written by women, to which many women writers contributed. This magazine had a major impact on the women's liberation movement in Japan. Later, those involved in Seitō published Nyonin Geijutsu (Women's Arts), and the activities of women writers became more active.

In 1948, nihonga (Japanese style painting) painter Uemura Shōen became the first woman to be awarded the Order of Culture for breaking new ground in bijin-ga (beautiful person picture) by depicting a different type of beauty than what had been painted before.

Religion

See also: Women in Buddhism and Women in ShintoThe first female Zen master in Japan was the Japanese abbess Mugai Nyodai (born 1223 - died 1298).

In 1872, the Japanese government issued an edict (May 4, 1872, Grand Council of State Edict 98) stating, "Any remaining practices of female exclusion on shrine and temple lands shall be immediately abolished, and mountain climbing for the purpose of worship, etc., shall be permitted". However, women in Japan today do not have complete access to all such places.

In 1998 the General Assembly of the Nippon Sei Ko Kai (Anglican Church in Japan) started to ordain women.

Health

At 87 years, the life expectancy of Japanese women is the longest of any sex anywhere in the world. Kane Tanaka lived for 119 years and 107 days, making her the second longest-lived verified person of all time.

Abortion in Japan is legal under some restrictions. The number per year has declined by 500,000 since 1975. Of the 200,000 abortions performed per year, however, 10% are teenage women, a number which has risen since 1975.

Beauty

The Japanese cosmetics industry is the second largest in the world, earning over $15 billion per year. The strong market for beauty products has been connected to the value placed on self-discipline and self-improvement in Japan, where the body is mastered through kata, repeated actions aspiring toward perfection, such as bowing.

In the Heian period, feminine beauty standards favored darkened teeth, some body fat, and eyebrows painted above the original (which were shaved).

Beauty corporations have had a role in creating contemporary standards of beauty in Japan since the Meiji era. For example, the Japanese cosmetics firm, Shiseido published a magazine, Hannatsubaki, with beauty advice for women emphasizing hair styles and contemporary fashion. The pre-war "modern girl" of Japan followed Western fashions as filtered through this kind of Japanese media.

Products reflect several common anxieties among Japanese women. Multiple polls suggest that women worry about "fatness, breast size, hairiness and bust size". The idealized figure of a Japanese woman is generally fragile and petite. Japanese beauty ideals favor small features and narrow faces. Big eyes are admired, especially when they have "double eyelids".

Another ideal is pale skin. Tanned skin was historically associated with the working-class, and pale skin associated with the nobility. Many women in Japan will take precaution to avoid the sun, and some lotions are sold to make the skin whiter.

By the 1970s, "cuteness" had emerged as a desirable aesthetic, which some scholars linked to a boom in comic books that emphasized young-looking girls, or Lolitas. While these characters typically included larger eyes, research suggests that it was not a traditional standard of beauty in Japan, preferred in medical research and described as "unsightly" by cosmetic researchers of the Edo era.

Clothing is another element in beauty standards for women in Japan, especially with traditional aesthetics. Again, femininity is a large factor; therefore, pinks, reds, bows, and frills are all found in their apparel. Kimonos, full-length silk robes, are worn by women on special occasions. Traditional patterns for women include many varieties of flowers found in Japan and across Asia such as cherry blossoms, lilies, chrysanthemums and camellia japonica flowers.

Some employers require their female workers to wear high heels and forbid eye glasses.

Contraception and sexuality

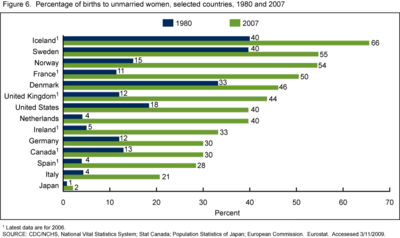

In Japan, the contraceptive pill was legalized in 1999, much later than in most Western countries. Its use is still low, with many couples preferring condoms. Sexuality in Japan has developed separately from mainland Asia, and Japan did not adopt the Confucian view of marriage in which chastity is highly valued. However, births outside marriage remain rare in Japan.

Laws of protection

Domestic violence

In Japan, domestic disputes have traditionally been seen as a result of negligence or poor support from the female partner. A partner's outburst can therefore be a source of shame to the wife or mother of the man they are supposed to care for. Because women's abuse would be detrimental to the family of the abused, legal, medical and social intervention in domestic disputes was rare.

After a spate of research during the 1990s, Japan passed the Prevention of Spousal Violence and the Protection of Victims act in 2001. The law referred to domestic violence as "a violation of the constitutional principle of equal rights between sexes". This law established protection orders from abusive spouses and created support centers in every prefecture, but women are still reluctant to report abuse to doctors out of shame or fear that the report would be shared with the abuser. A 2001 survey showed that many health professionals were not trained to handle domestic abuse and blamed women who sought treatment.

In 2013, 100,000 women reported domestic violence to shelters. Of the 10,000 entering protective custody at the shelter, nearly half arrived with children or other family members.

Stalking

Anti-stalking laws were passed in 2000 after the media attention given to the murder of a university student who had been a stalking victim. With nearly 21,000 reports of stalking in 2013, 90.3% of the victims were women and 86.9% of the perpetrators were men. Anti-stalking laws in Japan were expanded in 2013 to include e-mail harassment, after the widely publicized 2012 murder of a young woman who had reported such harassment to police. The number of stalker-related consultations with police continued to decline from 2017 to 2022, but in 2023, the number of consultations increased for the first time in six years, to a total of 19,843.

Sex trafficking

Main article: Sex trafficking in JapanJapanese and foreign women and girls have been victims of sex trafficking in Japan. They are raped in brothels and other locations and experience physical and psychological trauma. Japanese anti-sex trafficking legislation and laws have been criticized as being lacking.

Sexual assault

Surveys show that between 28% and 70% of women have been groped on train cars. Some railway companies designate women-only passenger cars though there are no penalties for men to ride in a women-only car. Gropers can be punished with seven years or less of jail time and/or face fines of just under $500.

The use of women-only cars in Japan has been critiqued from various perspectives. Some suggest that the presence of the cars makes women who choose not to use them more vulnerable. Public comment sometimes include the argument that women-only cars are a step too far in protecting women. Some academics have argued that the cars impose the burden of social segregation to women, rather than seeking the punishment of criminals. Another critique suggests the cars send the signal that men create a dangerous environment for women, who cannot protect themselves.

Geisha

Main article: Geisha

A geisha (芸者) is a traditional Japanese female entertainer who acts as a hostess and whose skills include performing various Japanese arts such as classical music, dance, games, serving tea and conversation, mainly to entertain male customers. Geisha are trained very seriously as skilled entertainers and are not to be confused with prostitutes. The training program starts from a young age, typically 15 years old, and can take anywhere from six months to three years.

A young geisha in training, under the age of 20, is called a maiko. Maiko (literally "dance girl") are apprentice geisha, and this stage can last for years. Maiko learn from their senior geisha mentor and follow them to all their engagements. Then at around the age of 20–22, the maiko is promoted to a full-fledged geisha in a ceremony called erikae (turning of the collar).

See also

- Birth control in Japan

- Class S (genre)

- Empress of Japan

- Family policy in Japan

- Feminism in Japan

- Gender Equality Bureau, Japan

- Good Wife, Wise Mother

- Gyaru

- Hinamatsuri

- Kyariaūman (career woman in Japan)

- Overview of gender inequality in Japan

- Shōjo

- Women in agriculture in Japan

- Yamato nadeshiko

- Nyonin Kinsei Women in Shinto

History:

- Kunoichi, female spies

- Onna-bugeisha, female warriors

References

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. - Japan

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. - Japan

- "Women in Parliaments: World Classification". www.ipu.org.

- OECD. "LFS by sex and age - indicators". Stats.oecd.org. Retrieved 2019-08-04.

- "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORTS. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- "Global Gender Gap Report 2024" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 11 January 2025.

- ^ The Road to Universal Suffrage (in Japanese). National Archives of Japan. Archived from the original on 26 November 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ 「民権ばあさん」没後100年 高知の記念館で企画展 (in Japanese). The Asahi Shimbun. 10 October 2020. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- "Birth of the Constitution of Japan - Chronological Table". National Diet Library, Japan. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Borovoy, Amy (2005). The too-good wife: alcohol, codependency, and the politics of nurturance in postwar Japan. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24452-4.

- Asao, Kohei; Khera, Purva; Vasishth, Mahima (2024-07-01). "Why Such Few Women in Leadership Positions in Japan?: Japan". Selected Issues Papers. 2024 (024). doi:10.5089/9798400281655.018.A001.

- "Unleashed Potential: The State of Women in Tech in Japan in 2023 - Women in Tech Sales". 2023-06-27. Retrieved 2025-01-11.

- "Significant gender pay gap persists among Japan-listed corporations, with women earning 70% of what men earn". WTW. Retrieved 2025-01-11.

- ^ Soble, Jonathan (1 January 2015). "To Rescue Economy, Japan Turns to Supermom". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- ^ Nohara, Yoshiaki (21 January 2014). "Goldman's Matsui Turns Abe to Womenomics for Japan Growth". Bloomberg.

- ^ 男女間賃金格差(我が国の現状) (in Japanese). Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office. Archived from the original on 2 January 2025. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- 第1節 教育をめぐる状況 (in Japanese). Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office. Archived from the original on 13 December 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- Canada, Asia Pacific Foundation of. ""Womenomics" in Japan". Asia Pacific Curriculum. Retrieved 2025-01-11.

- 日本人の平均寿命、3年ぶりに延びる 世界で女性は1位キープも、男性は5位に下がる (in Japanese). Sankei Shimbun. 26 July 2024. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- "Country Profile Japan". Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security. Archived from the original on 4 January 2025. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- "Japan moves up to 118th in the world for gender equality".

- 男女共同参画に関する国際的な指数 (in Japanese). Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office. 12 June 2024. Archived from the original on 7 October 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- "Heroines: Heian Period (Women in World History Curriculum)". www.womeninworldhistory.com.

- Ekken, Kaibara (2010). Onna Daigaku A Treasure Box of Women's Learning. Gardners Books. ISBN 978-0-9559796-7-5.

- The Meiji Reforms and Obstacles for Women Japan, 1878–1927

- ^ Lebra, Takie Sugiyama (1985). Japanese women: constraint and fulfillment (Pbk. ed.). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1025-2.

- Tamanoi, Mariko Asano (October 1990). "Women's Voices: Their Critique of the Anthropology of Japan". Annual Review of Anthropology. 19 (1): 17–37. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.000313.

- Rethinking Japan: Social sciences, ideology & thought, by Adriana Boscaro, Franco Gatti, Massimo Raveri, pp. 164-173

- "Employment - Employment rate - OECD Data". theOECD. Retrieved 2019-11-03.

- Fox, Margalit (January 1, 2013). "Beate Gordon, Long-Unsung Heroine of Japanese Women's Rights, Dies at 89". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

Correction: January 4, 2013

- Dower, pp. 365-367

- ^ Chanlett-Avery, Emma; Nelson, Rebecca M. (2014). ""Womenomics" in Japan: In Brief" (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

- ^ Mikanagi, Yumiko (2011). "The Japanese conception of citizenship". The Routledge Handbook of Japanese Politics: 130–139.

- 明窓・女性首相と言うけれど… (in Japanese). The San-in Chuo Shimpo. 19 July 2024. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- 職主な新聞記事(平成22年秋) (PDF) (in Japanese). Cabinet Office (Japan). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Eto, Mikiko (2010-06-01). "Women and Representation in Japan". International Feminist Journal of Politics. 12 (2): 177–201. doi:10.1080/14616741003665227. ISSN 1461-6742. S2CID 142938281.

- "Women in Parliaments: World Classification". archive.ipu.org. Retrieved 2021-12-01.

- ^ McCurry, Justin (26 October 2021). "'It is bullying, pure and simple': being a woman in Japanese politics". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Japan's lower house has fewer women despite empowerment law". Mainichi Daily News. 2021-11-01. Retrieved 2021-11-12.

- Abe, Shinzo (25 September 2013). "Unleashing the Power of 'Womenomics'". Wall Street Journal. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Cabinet Office, Gender Equality Bureau. "Perceptions of Gender Inequality" (PDF). www.gender.go.jp/. Japan Cabinet Office Gender Equality Bureau. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Eto, Mikiko (2021). Women and political inequality in Japan: gender-imbalanced democracy. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-05691-1. OCLC 1176320849.

- "Record no. of female city mayors, assembly members elected in Japan's unified local polls". Mainichi Daily News. 2019-04-22. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- "Record 35 women elected to Japan upper house". Kyodo News. 11 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- "Record 35 women elected to Japan upper house". The Mainichi. 11 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- "Record 35 Women Win Upper House Seats in Sun. Election". Nippon.com. 11 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Gaunder, Alisa (17 March 2015). "Quota Nonadoption in Japan: The Role of the Women's Movement and the Opposition". Politics & Gender. 11 (1): 176–186. doi:10.1017/S1743923X1400066X. ISSN 1743-923X. S2CID 145457053.

- ^ Bochel, Catherine; Bochel, Hugh; Kasuga, Masashi; Takeyasu, Hideko (2003-04-01). "Against the System? Women in Elected Local Government in Japan". Local Government Studies. 29 (2): 19–31. doi:10.1080/03003930308559368. ISSN 0300-3930. S2CID 154284863.

- Gaunder, Alisa (26 January 2016). "The DPJ and Women: The Limited Impact of the 2009 Alternation of Power on Policy and Governance". Journal of East Asian Studies. 12 (3): 441–466. doi:10.1017/S1598240800008092. ISSN 1598-2408.

- ^ Tomoaki, Iwai (1993). ""The Madonna Boom": Women in the Japanese Diet". Journal of Japanese Studies. 19 (1): 103–120. doi:10.2307/132866. ISSN 0095-6848. JSTOR 132866.

- ^ Kage, Rieko; Rosenbluth, Frances M.; Tanaka, Seiki (27 July 2018). "What Explains Low Female Political Representation? Evidence from Survey Experiments in Japan". Politics & Gender. 15 (2): 285–309. doi:10.1017/S1743923X18000223. ISSN 1743-923X. S2CID 53413394.

- Takeda, Hiroko (2011). "Gender-related social policy". The Routledge Handbook of Japanese Politics: 212–222.

- ^ Dalton, Emma (2019-11-01). "A feminist critical discourse analysis of sexual harassment in the Japanese political and media worlds". Women's Studies International Forum. 77: 102276. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2019.102276. ISSN 0277-5395. S2CID 203519380.

- Dalton, Emma (8 October 2021). "The Overlooked Issue of Sexual Harassment in Japanese Politics". Tokyo Review. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- 男女間の賃金格差の要因とその対応等 (PDF) (in Japanese). Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- 職場のハラスメントに関する実態調査 結果概要(令和5年度厚生労働省委託事業) (PDF) (in Japanese). Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ Hendry, Joy (1986). Marriage in changing Japan: community and society (1st Tuttle ed.). Rutland, Vt.: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN 0-8048-1506-2.

- Morsbach, Helmut (1978). Corbyn, Marie (ed.). Aspects of Japanese Marriage. Penguin Books. p. 98.

- Hirata, Keiko; Warschauer, Mark (2014). Japan: the paradox of harmony. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-300-18607-9.

- Nemoto, Kumiko (September 2013). "Long Working Hours and the Corporate Gender Divide in Japan". Gender, Work & Organization. 20 (5): 512–527. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2012.00599.x.

- Anne Allison. 2000. Japanese Mothers and Obentōs: The Lunch Box as Ideological State Apparatus. Permitted and Prohibited Desires: Mothers, Comics, and Censorship in Japan, pp. 81-104. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. http://fds.duke.edu/db/attachment/1111

- "働く女性の状況" (PDF). Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

- Yu, p. 494

- Yan, Sophia; Ogura, Junko (7 December 2015). "Japan slashes target for women in senior positions". CNN. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Cooper, Jessica (2013). The Roles of Women, Animals, and Nature in Traditional Japanese and Western Folk Tales Carry Over into Modern Japanese and Western Culture. USA: East Tennessee State University.

- Kitamura, Mariko (1982). The Animal-Wife: A Comparison of Japanese Folktales with their European Counterparts. Los Angeles: University of California.

- Moscicki, Helen (8 July 1944). : 19.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Economist. "Holding back half the nation". The Economist. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Bae, Jihey (2010). "Gender Role Division in Japan and Korea: The Relationship between Realities and Attitudes". Journal of Political Science & Sociology (13): 71–85.

- Borovoy, Amy (2005). The Too-Good Wife: Alcohol, codependency, and the politics of nurturance in postwar Japan. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-520-24452-4.

- Yoshizumi, Kyoko (1995). Fujimura-Fanselow, Kumiko; Kameda, Atsuko (eds.). Japanese Women: new perspectives on the past, present and future. New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York]. pp. 183–197.

- Van Houten, Elizabeth. (2005). Women in the Japanese world. Philadelphia: Mason Crest Publishers. p. 38. ISBN 1-59084-859-4. OCLC 761397473.

- Iwasaki, Yasu (1930). "Divorce in Japan". American Journal of Sociology. 36 (3): 435–446. doi:10.1086/215417. S2CID 143833023.

- ^ "Population, Family and Household" (PDF). Japan Cabinet Office Gender Equality Bureau. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Umeda, S. (2016, February 26). Global Legal Monitor. Retrieved December 04, 2016, from https://www.loc.gov/law/foreign-news/article/japan-new-instructions-allow-women-to-remarry-100-days-after-divorce/

- "Japanese women in court fight to keep their surnames after marriage". The Guardian. Reuters. 11 December 2015. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- "Japan top court upholds law on married couples' surnames - BBC News". Bbc.com. 2015-12-16. Retrieved 2019-08-04.

- Niwa, Akiko (1993). "The Formation of the Myth of Motherhood in Japan". US Japan Women's Journal. 4: 70–82.

- THE UNIQUE IDENTITY OF JAPANESE GIRLS

- Sanger, David (14 June 1990). "Tokyo official ties birth decline to higher education". New York Times. New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ type. "East Asia/Southeast Asia :: Japan — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2019-08-04.

- (Cabinet Office), Naikakufu (2005). Shōshika shakai hakusho (Heisei 17nen han) – Shōshika taisaku no genjō to kadai . Tokyo: Gyosei.

- Boling, Patricia (1998). "Family Policy in Japan". Journal of Social Policy. 27 (2): 173–190. doi:10.1017/s0047279498005285. S2CID 145757734.

- Schoppa, Leonard J. (2008). Race for the exits: the unraveling of Japan's system of social protection (. ed.). Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7445-3.

- Lenz, Ilse (2006). "From Mothers of the Nation to Global Civil Society: The changing role of the Japanese women's movement in Globalization". Social Science Japan. 9 (1): 91–102. doi:10.1093/ssjj/jyk011.

- Placier, Peggy; Huang, Haigen (October 2015). "Four Generations of Women's Educational Experience in a Rural Chinese Community". Gender and Education. 27 (6): 599–617. doi:10.1080/09540253.2015.1069799. S2CID 143211123.

- Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office. "Education and Research Fields" (PDF). gender.go.jp. Japan Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Burton, Margaret Emerstine (1914). The Education of Women in Japan. Cambridge, MA: Fleming H. Revell (Harvard University Preservation Program).

- ^ Koyama, Takashi (1961). The changing social position of women in Japan (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ Patessio, Mara (December 2013). "Women getting a 'university' education in Meiji Japan: discourses, realities, and individual lives". Japan Forum. 25 (4): 556–581. doi:10.1080/09555803.2013.788053. S2CID 143515278.

- "Gakko kihon chosa - Heisei 24 nendo (sokuho) kekka no gaiyo" (PDF). MEXT. Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports and Technology. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- Cabinet Office, Gender Equality Bureau (April 2014). "White Paper on Gender Equality 2013". Statistical Topics (Japanese). 80. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ 時代を切り拓いた女性作家たち (in Japanese). National Diet Library. Archived from the original on 30 December 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- 上村松園―女性初の文化勲章― (in Japanese). National Archives of Japan. Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- "Mugai Nyodai, First Woman to Head a Zen Order". Buddhism Site. Lisa Erickson. Retrieved 2013-10-16.

- Susan Sachs (1998-11-22). "Japanese Zen Master Honored by Her Followers". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-11-12.

-

- Dewitt, Lindsey Elizabeth (March 2016). "Envisioning and Observing Women's Exclusion from Sacred Mountains in Japan". Journal of Asian Humanities at Kyushu University. 1: 19–28. doi:10.5109/1654566. hdl:1854/LU-8636481. S2CID 55419374.

- DeWitt, Lindsey Elizabeth (1 March 2016). "Envisioning and Observing Women's Exclusion from Sacred Mountains in Japan". semanticscholar.org. S2CID 55419374.

- "pdf" (PDF). semanticscholar.org. S2CID 55419374. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2019.

- "When churches started to ordain women". Religioustolerance.org. Retrieved 2019-08-04.

- "119歳 福岡市の田中カ子さん死去 ギネスで世界最高齢に認定". NHK News Web (in Japanese). 25 April 2022. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- Cabinet Office, Gender Equality Bureau. "Women and Men in Japan". Gender.go.jp. Japanese Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ Miller, Laura (2006). Beauty up: exploring contemporary Japanese body aesthetics (2. ed.). Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24508-2.

- Morris, Ivan (1995). The world of the shining prince: court life in ancient Japan ( ed.). New York : Kodansha International. ISBN 978-1-56836-029-4.

- ^ Keene, Donald (1989). "The Japanese Idea of Beauty". The Wilson Quarterly. 13 (1): 128–135. JSTOR 40257465.

- ^ Cho Kyo (2012). The search for the beautiful woman a cultural history of Japanese and Chinese beauty. Translated by Kyoko Selden. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-1895-6.

- "High heels at work are necessary, says Japan's labour minister". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse in Tokyo. 5 June 2019.

- "Japan 'glasses ban' for women at work sparks backlash". BBC News. 8 November 2019.

- "Changing Patterns of Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States". CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. May 13, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- Cosgrove-Mather, Bootie (20 August 2004). "Japanese Women Shun The Pill". CBS News. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- Lebra, Takie (1984). Japanese Women: Constraint and Fulfillment. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ Nemoto, Keiko; Rodriguez, Rachel; Valhmu, Lucy Mkandawire (May 2006). "Exploring the Health Care Needs of Women in Abusive Relationships in Japan". Health Care for Women International. 27 (4): 290–306. doi:10.1080/07399330500511774. PMID 16595363. S2CID 275052.

- The Gender Equality Bureau of the Cabinet Office (2002). Heisei 14 nenban danjo kyodo sankaku hakusho . Tokyo: Zaimusyou insatsu Kyoku.

- Tokyoto Iryo Syakai Jigyo Kyokai Iryo Fukushi Mondai Kenkyu Kai (2001). "Iryokikan ni okeru domesutikku baiorensu ni tsuite no chosa hokokusho ". Josei No Anzen to Kenko No Tameno Shien Kyoiku Senta Tushin. 3: 23–38.

- ^ Cabinet Office, Gender Equality Bureau. "Violence against Women" (PDF). gender.go.jp. Japanese Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- "Stalker-killer's life term upheld". The Japan Times. December 21, 2005. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- Aquino, Faith (2013-06-27). "Japan toughens anti-stalking laws, includes repeated emailing as harassment". Japan Daily Press. Archived from the original on 2015-09-28. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- "ストーカーの相談が6年ぶり増加 禁止命令は最多、加害者対策を強化". The Asahi Shimbun. 28 March 2024. Archived from the original on 6 April 2024. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- "Seven Cambodians Rescued in Sex Trafficking Bust in Japan". VOA. January 24, 2017.

- "Why are foreign women continuing to be forced into prostitution in Japan?". Mainichi Daily News. June 10, 2017.

- ^ "The Sexual Exploitation of Young Girls in Japan Is 'On the Increase,' an Expert Says". Time. October 29, 2019.

- ^ "For vulnerable high school girls in Japan, a culture of 'dates' with older men". The Washington Post. May 16, 2017.

- "Schoolgirls for sale: why Tokyo struggles to stop the 'JK business'". The Guardian. June 15, 2019.

- "LIGHTHOUSE NGO SERVES AS BEACON OF HOPE FOR VICTIMS OF SEX TRAFFICKING". UW–Madison News. May 15, 2018.

- "Tokyo police act on train gropers"

- ^ Horii, Mitsutoshi; Burgess, Adam (February 2012). "Constructing sexual risk: 'Chikan', collapsing male authority and the emergence of women-only train carriages in Japan". Health, Risk & Society. 14 (1): 41–55. doi:10.1080/13698575.2011.641523. S2CID 143965339.

- "Untitled Document". 2007-12-26. Archived from the original on December 26, 2007. Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- ^ "Japan Tries Women Only Train Cars to Stop Groping: Tokyo Subway Experiment Attempts to Slow Epidemic of Subway Fondling" An ABC News article.

- "Women Only Cars on Commuter Trains Cause Controversy in Japan"

- Freedman, Alisa (1 March 2002). "Commuting Gazes: Schoolgirls, Salarymen, and Electric Trains in Tokyo". The Journal of Transport History. 23 (1): 23–36. doi:10.7227/TJTH.23.1.4. S2CID 144758844.

- ^ Dalby, Liza (1992). "Kimona and Geisha". The Threepenny Review. 51: 30–31.

Further reading

- Adams, Kenneth Alan (2009). "Modernization and dangerous women in Japan". The Journal of Psychohistory. 37 (1): 33–44. PMID 19852238. ProQuest 203930080.

- Akiba, Fumiko (March 1998). "Women At Work Toward Equality In The Japanese Workplace". Look Japan. Archived from the original on 2002-03-21.

- Aoki, Debora. Widows of Japan: An anthropological perspective (Trans Pacific Press, 2010).

- Bardsley, Jan. Women and Democracy in Cold War Japan (Bloomsbury, 2015) excerpt.

- Bernstein, Lee Gail. ed. Recreating Japanese Women, 1600–1945 (U of California Press, 1991).

- Brinton, Mary C. Women and the economic miracle: Gender and work in postwar Japan (U of California Press, 1993).

- Copeland, Rebecca L. Lost leaves: women writers of Meiji Japan (U of Hawaii Press, 2000).

- Faison, Elyssa. Managing women: Disciplining labor in modern Japan (U of California Press, 2007).

- Francks, Penelope (June 2015). "Was Fashion a European Invention?: The Kimono and Economic Development in Japan". Fashion Theory. 19 (3): 331–361. doi:10.2752/175174115X14223685749368. S2CID 194189967.

- Garon, Sheldon (1 August 2010). "State and family in modern Japan: a historical perspective". Economy and Society. 39 (3): 317–336. doi:10.1080/03085147.2010.486214. S2CID 144451445.

- Gayle, Curtis Anderson. Women's history and local community in postwar Japan (Routledge, 2013). excerpt

- Gelb, J; Estevez-Abe, M (1 October 1998). "Political women in Japan: a case study of the Seikatsusha network movement". Social Science Japan Journal. 1 (2): 263–279. doi:10.1093/ssjj/1.2.263.

- Goldstein-Gidoni, Ofra. Housewives of Japan.

- Gulliver, Katrina. Modern women in China and Japan: Gender, feminism and global modernity between the wars (IB Tauris, 2012).

- Hastings, Sally A. "Gender and Sexuality in Modern Japan." in A Companion to Japanese History (2007): 372+.

- Hastings, Sally A. (1 June 1993). "The Empress' New Clothes and Japanese Women, 1868–1912". The Historian. 55 (4): 677–692. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1993.tb00918.x.

- LaFleur, William R. Liquid Life: Abortion and Buddhism in Japan (Princeton UP, 1992).

- Lebra, Joyce C. Women in changing Japan (Routledge, 20190 ASIN B07S9H3S18

- McAndrew, Malia (2014). "Beauty, Soft Power, and the Politics of Womanhood During the U.S. Occupation of Japan, 1945–1952". Journal of Women's History. 26 (4): 83–107. doi:10.1353/jowh.2014.0063. S2CID 143829831. Project MUSE 563306.

- Patessio, Mara. Women and public life in early Meiji Japan: The development of the feminist movement (U of Michigan Press, 2020). ASIN 192928067X

- Robins-Mowry, Dorothy. The hidden sun: Women of modern Japan (Westview Press, 1983) ASIN 0865314217

- Sato, Barbara. The New Japanese Woman: Modernity, Media, and Women in Interwar Japan (Duke UP, 2003). ASIN 0822330083

- Tipton, Elise K. (1 May 2009). "How to Manage a Household: Creating Middle Class Housewives in Modern Japan". Japanese Studies. 29 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1080/10371390902780555. S2CID 144960231.

External links

- Japanese Equal Employment Opportunity Law

- "Gender and Sexuality in Japan" syllabus by Professor Jeffry T. Hester

| Japan articles | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

| ||||||||||||

| Geography | |||||||||||||

| Politics |

| ||||||||||||

| Economy | |||||||||||||

| Society | |||||||||||||