| Revision as of 03:17, 3 February 2013 editMarkj99 (talk | contribs)56 edits →Evaluation for health effects: significant results in subgroup← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:38, 3 February 2013 edit undoJytdog (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers187,951 edits →Evaluation for health effects: enough of this; just added blockquote with the results.Next edit → | ||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

| When the data from both groups was pooled and analyzed, there was no ] difference between groups taking glucosamine HCl, chondroitin sulfate, glucosamine/chondroitin; and those taking a placebo. | When the data from both groups was pooled and analyzed, there was no ] difference between groups taking glucosamine HCl, chondroitin sulfate, glucosamine/chondroitin; and those taking a placebo. | ||

| The authors of the study analyzed the moderate-to-severe pain group and found that: <blockquote>treatment effects ... were more substantial. Results for the primary outcome in this stratum, which included 22 percent of the patients in the trial, indicated that combined treatment was significantly more effective than placebo (24.9 percentage points higher, P=0.002). As compared with placebo, however, celecoxib (difference, 15.1 percentage points; P=0.06), glucosamine (difference, 11.4 percentage points; P=0.17), and chondroitin sulfate (difference, 7.1 percentage points; P=0.39) were not significantly better. Similarly, the OMERACT–OARSI response rate ranged from 26.4 percentage points higher with combined treatment (P=0.001) to 10.0 percentage points higher with chondroitin sulfate (P=0.24), as compared with placebo.... Analysis of the prespecified subgroup of patients with moderate-to-severe pain demonstrated that combination therapy significantly decreased knee pain related to osteoarthritis, as measured by the primary outcome or by the OMERACT–OARSI response rate. We did not identify significant benefits associated with the use of glucosamine or chondroitin sulfate alone. Although the results for glucosamine did not reach significance, the possibility of a positive effect in the subgroup of patients with moderate-to-severe pain cannot be excluded, since the difference from placebo in the OMERACT–OARSI response rate approached significance in this group....Treatment effects were more substantial in the subgroup of patients with moderate-to-severe pain, but the relatively small numbers of patients in this subgroup may have limited the study's power to demonstrate significant benefits in the glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and celecoxib groups. For example, as compared with placebo, celecoxib therapy was associated with a clinically meaningful difference in the primary outcome measure of 15 percentage points, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. | |||

| But in the moderate-to-severe pain subgroup, 79% of those taking the glucosamine/chondroitin combination had a 20% (or more) reduction in pain, while just 51% in the placebo group had a similar reduction; and this difference ''was'' statistically significant. However, the authors suggested that the sample size of this subgroup may be too small to draw reliable inferences. | |||

| <ref name=GAIT2006>{{cite journal |author=Clegg DO |title=Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=354 |issue=8 |pages=795–808 |year=2006 |month=February |pmid=16495392 |doi=10.1056/NEJMoa052771 |author-separator=, |author2=Reda DJ |author3=Harris CL |display-authors=3 |last4=Klein |first4=Marguerite A. |last5=O'Dell |first5=James R. |last6=Hooper |first6=Michele M. |last7=Bradley |first7=John D. |last8=Bingham |first8=Clifton O. |last9=Weisman |first9=Michael H.}}</ref> | <ref name=GAIT2006>{{cite journal |author=Clegg DO |title=Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=354 |issue=8 |pages=795–808 |year=2006 |month=February |pmid=16495392 |doi=10.1056/NEJMoa052771 |author-separator=, |author2=Reda DJ |author3=Harris CL |display-authors=3 |last4=Klein |first4=Marguerite A. |last5=O'Dell |first5=James R. |last6=Hooper |first6=Michele M. |last7=Bradley |first7=John D. |last8=Bingham |first8=Clifton O. |last9=Weisman |first9=Michael H.}}</ref> </blockquote> | ||

| In a follow-up study, 572 patients from the GAIT trial continued the supplementation for 2 years. After 2 years of supplementation with glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, alone or in combination, there was no benefit in slowing the loss of cartilage, in terms of joint space width, when compared to a placebo.<ref name=GAIT2008>{{cite journal |author=Sawitzke AD |title=The effect of glucosamine and/or chondroitin sulfate on the progression of knee osteoarthritis: a report from the glucosamine/chondroitin arthritis intervention trial. |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=58 |issue=10 |pages=3183-91 |year=2008 |month=October |pmid=18821708.}}</ref> Further, in another 2-year follow-up study, there was no significant pain reduction or improved function when compared to a placebo.<ref name=GAIT2010>{{cite journal |author=Sawitzke AD |title=Clinical efficacy and safety of glucosamine, chondroitin sulphate, their combination, celecoxib or placebo taken to treat osteoarthritis of the knee: 2-year results from GAIT. |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=69 |issue=8 |pages=1459-64 |year=2010 |month=August |pmid=20525840.}}</ref> ] stated, "The counter anion of the glucosamine salt (i.e. chloride or sulfate) is unlikely to play any role in the action or pharmacokinetics of glucosamine".<ref name="PDR Health"></ref> | In a follow-up study, 572 patients from the GAIT trial continued the supplementation for 2 years. After 2 years of supplementation with glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, alone or in combination, there was no benefit in slowing the loss of cartilage, in terms of joint space width, when compared to a placebo.<ref name=GAIT2008>{{cite journal |author=Sawitzke AD |title=The effect of glucosamine and/or chondroitin sulfate on the progression of knee osteoarthritis: a report from the glucosamine/chondroitin arthritis intervention trial. |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=58 |issue=10 |pages=3183-91 |year=2008 |month=October |pmid=18821708.}}</ref> Further, in another 2-year follow-up study, there was no significant pain reduction or improved function when compared to a placebo.<ref name=GAIT2010>{{cite journal |author=Sawitzke AD |title=Clinical efficacy and safety of glucosamine, chondroitin sulphate, their combination, celecoxib or placebo taken to treat osteoarthritis of the knee: 2-year results from GAIT. |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=69 |issue=8 |pages=1459-64 |year=2010 |month=August |pmid=20525840.}}</ref> ] stated, "The counter anion of the glucosamine salt (i.e. chloride or sulfate) is unlikely to play any role in the action or pharmacokinetics of glucosamine".<ref name="PDR Health"></ref> | ||

Revision as of 03:38, 3 February 2013

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name (3R,4R,5S)-3-Amino-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxane-2,4,5-triol | |||

| Other names

2-Amino-2-deoxy-glucose Chitosamine | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| CAS Number | |||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| Beilstein Reference | 1723616 | ||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.020.284 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| Gmelin Reference | 720725 | ||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Glucosamine | ||

| PubChem CID | |||

| UNII | |||

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |||

InChI

| |||

SMILES

| |||

| Properties | |||

| Chemical formula | C6H13NO5 | ||

| Molar mass | 179.172 g·mol | ||

| Density | 1.563 g/mL | ||

| Melting point | 150 °C (302 °F; 423 K) | ||

| log P | -2.175 | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 12.273 | ||

| Basicity (pKb) | 1.724 | ||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C , 100 kPa).

| |||

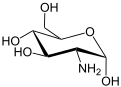

Glucosamine (C6H13NO5) is an amino sugar and a prominent precursor in the biochemical synthesis of glycosylated proteins and lipids. Glucosamine is part of the structure of the polysaccharides chitosan and chitin, which compose the exoskeletons of crustaceans and other arthropods, cell walls in fungi and many higher organisms. Glucosamine is one of the most abundant monosaccharides. It is produced commercially by the hydrolysis of crustacean exoskeletons or, less commonly by fermentation of a grain such as corn or wheat. In the US it is one of the most common non-vitamin, non-mineral, dietary supplements used by adults.

Biochemistry

Glucosamine is naturally present in the shells of shellfish, animal bones and bone marrow. It is also present in some fungi, such as Aspergillus niger.

Glucosamine was first prepared in 1876 by Georg Ledderhose by the hydrolysis of chitin with concentrated hydrochloric acid. The stereochemistry was not fully determined until the 1939 work of Walter Haworth. D-Glucosamine is made naturally in the form of glucosamine-6-phosphate, and is the biochemical precursor of all nitrogen-containing sugars. Specifically, glucosamine-6-phosphate is synthesized from fructose 6-phosphate and glutamine by glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase as the first step of the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway. The end-product of this pathway is Uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc), which is then used for making glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans, and glycolipids.

As the formation of glucosamine-6-phosphate is the first step for the synthesis of these products, glucosamine may be important in regulating their production; however, the way that the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway is actually regulated, and whether this could be involved in contributing to human disease remains unclear.

Use as a dietary supplement

Oral glucosamine is a dietary supplement and is not a pharmaceutical drug. It is illegal in the US to market any dietary supplement as a treatment for any disease or condition. Glucosamine is marketed to support the structure and function of joints and the marketing is targeted to people suffering from osteoarthritis. Commonly sold forms of glucosamine are glucosamine sulfate, glucosamine hydrochloride, and N-acetylglucosamine. Glucosamine is often sold in combination with other supplements such as chondroitin sulfate and methylsulfonylmethane. Of the three commonly available forms of glucosamine, only glucosamine sulfate is given a "likely effective" rating for treating osteoarthritis.

Evaluation for health effects

Since glucosamine is a precursor for glycosaminoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans are a major component of joint cartilage, supplemental glucosamine may or may not influence cartilage structure, and so may or may not apply to alleviation of arthritis. Its use as a therapy for osteoarthritis appears safe, but there is not yet unequivocal evidence for its effectiveness. There have been multiple clinical trials testing glucosamine as a potential medical therapy for osteoarthritis, but results have been inconclusive at best; contradictory at worst.

In 2006, the NIH National Institutes of Health funded a 24 week, 12.5 million-dollar multicenter clinical trial (the GAIT trial) to study the effect of chondroitin sulfate, glucosamine hydrochloride, chondroitin/glucosamine in combination, and celecoxib as a treatment for knee-pain in two groups of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: Patients with mild pain (n=1229), and patients with moderate to severe pain (n=354).

When the data from both groups was pooled and analyzed, there was no statistically significant difference between groups taking glucosamine HCl, chondroitin sulfate, glucosamine/chondroitin; and those taking a placebo.

The authors of the study analyzed the moderate-to-severe pain group and found that:

treatment effects ... were more substantial. Results for the primary outcome in this stratum, which included 22 percent of the patients in the trial, indicated that combined treatment was significantly more effective than placebo (24.9 percentage points higher, P=0.002). As compared with placebo, however, celecoxib (difference, 15.1 percentage points; P=0.06), glucosamine (difference, 11.4 percentage points; P=0.17), and chondroitin sulfate (difference, 7.1 percentage points; P=0.39) were not significantly better. Similarly, the OMERACT–OARSI response rate ranged from 26.4 percentage points higher with combined treatment (P=0.001) to 10.0 percentage points higher with chondroitin sulfate (P=0.24), as compared with placebo.... Analysis of the prespecified subgroup of patients with moderate-to-severe pain demonstrated that combination therapy significantly decreased knee pain related to osteoarthritis, as measured by the primary outcome or by the OMERACT–OARSI response rate. We did not identify significant benefits associated with the use of glucosamine or chondroitin sulfate alone. Although the results for glucosamine did not reach significance, the possibility of a positive effect in the subgroup of patients with moderate-to-severe pain cannot be excluded, since the difference from placebo in the OMERACT–OARSI response rate approached significance in this group....Treatment effects were more substantial in the subgroup of patients with moderate-to-severe pain, but the relatively small numbers of patients in this subgroup may have limited the study's power to demonstrate significant benefits in the glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and celecoxib groups. For example, as compared with placebo, celecoxib therapy was associated with a clinically meaningful difference in the primary outcome measure of 15 percentage points, but the difference did not reach statistical significance.

In a follow-up study, 572 patients from the GAIT trial continued the supplementation for 2 years. After 2 years of supplementation with glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, alone or in combination, there was no benefit in slowing the loss of cartilage, in terms of joint space width, when compared to a placebo. Further, in another 2-year follow-up study, there was no significant pain reduction or improved function when compared to a placebo. PDR stated, "The counter anion of the glucosamine salt (i.e. chloride or sulfate) is unlikely to play any role in the action or pharmacokinetics of glucosamine".

Where clinical trials have furnished positive results showing glucosamine efficacy, the studies were deemed to be of poor quality due to shortcomings in their methods, including small size, short duration, poor analysis of drop-outs, and unclear procedures for blinding. Alternately, several independent studies did not detect any benefit of glucosamine supplementation on osteoarthritis.

A systematic review found that effect sizes from glucosamine supplementation were highest in industry-funded studies and lowest in independent studies. A Cochrane 2005 meta-analysis of glucosamine therapy for osteoarthritis found that only the Rotta brand of glucosamine appeared to be superior to placebo in the treatment of pain and functional impairment resulting from symptomatic osteoarthritis. However, when the low quality and older studies were discounted and only those using the highest-quality design were considered, there was no difference from placebo treatment.

Due to these controversial results, some meta-analyses have attempted to evaluate the efficacy of glucosamine, A meta-analysis concluded: "Compared with placebo, glucosamine, chondroitin, and their combination do not reduce joint pain or have an impact on narrowing of joint space. Health authorities and health insurers should not cover the costs of these preparations, and new prescriptions to patients who have not received treatment should be discouraged." .

Use of glucosamine in veterinary medicine exists, but one study judged extant research too flawed to be of value in guiding treatment of horses.

Adverse effects

Clinical studies have consistently reported that glucosamine appears safe. However, a recent Université Laval study shows that people taking glucosamine tend to go beyond recommended guidelines, as they do not feel any positive effects from the drug. Beyond recommended dosages, researchers found in preliminary studies that glucosamine may damage pancreatic cells, possibly increasing the risk of developing diabetes.

Adverse effects, which are usually mild and infrequent, include stomach upset, constipation, diarrhea, headache and rash.

Since glucosamine is usually derived from the shells of shellfish while the allergen is within the flesh of the animals, it is probably safe even for those with shellfish allergy. However, many manufacturers of glucosamine derived from shellfish include a warning that those with a seafood allergy should consult a healthcare professional before taking the product. Alternative, non-shellfish derived forms of glucosamine are available.

Another concern has been that the extra glucosamine could contribute to diabetes by interfering with the normal regulation of the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway, but several investigations have found no evidence that this occurs. A manufacturer-supported review conducted by Anderson et al. in 2005 summarizes the effects of glucosamine on glucose metabolism in in vitro studies, the effects of oral administration of large doses of glucosamine in animals and the effects of glucosamine supplementation with normal recommended dosages in humans, concluding that glucosamine does not cause glucose intolerance and has no documented effects on glucose metabolism. Other studies conducted in lean or obese subjects concluded that oral glucosamine at standard doses does not cause or significantly worsen insulin resistance or endothelial dysfunction.

Possibility of bioavailability

Recent studies provide preliminary evidence that glucosamine may be bioavailable in the synovial fluid after oral administration of crystalline glucosamine sulfate in osteoarthritis patients, as steady state glucosamine concentrations in plasma and synovial fluid were correlated. If eventually proven, glucosamine sulfate uptake in synovial fluid may be as much as 20%, or as little as a negligible amount, indicating no biological significance.

Preliminary research

If glucosamine sulfate actually is proven to be effective in patients with osteoarthritis, it may result from anti-inflammatory activity, stimulation of proteoglycan synthesis, decrease in catabolic activity of chondrocytes inhibiting the synthesis of proteolytic enzymes and other substances that contribute to cartilage integrity, or have no effect at all.

As a substrate of the GAG matrix, glucosamine is postulated to stimulate synovial production of hyaluronic acid or possibly to inhibit liposomal enzymes.

Legal status

United States

In the United States, glucosamine is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for medical use in humans. Since glucosamine is classified as a dietary supplement in the US, safety and formulation are solely the responsibility of the manufacturer; evidence of safety and efficacy is not required as long as it is not advertised as a treatment for a medical condition. The U.S. National Institutes of Health is currently conducting a study of supplemental glucosamine in obese patients, since this population may be particularly sensitive to any effects of glucosamine on insulin resistance.

Europe

In most of Europe, glucosamine is approved as a medical drug and is sold in the form of glucosamine sulfate. In this case, evidence of safety and efficacy is required for the medical use of glucosamine and several guidelines have recommended its use as an effective and safe therapy for osteoarthritis. The Task Force of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) committee has granted glucosamine sulfate a level of toxicity of 5 in a 0-100 scale, and recent OARSI (OsteoArthritis Research Society International) guidelines for hip and knee osteoarthritis indicate an acceptable safety profile.

See also

References

- ^ Horton D, Wander JD (1980). The Carbohydrates. Vol. Vol IB. New York: Academic Press. pp. 727–728. ISBN ].

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - "Vegan Glucosamine FAQ". Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- "Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults and Children: United States, 2007" (PDF). National Center for Health Statistics. December 10, 2008. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- "Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies on a request from the European Commission on the safety of glucosamine hydrochloride from Aspergillus niger as food ingredient". The EFSA Journal. 1099: 1–19. 2009.

- Georg Ledderhose (1876). "Über salzsaures Glycosamin". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 9 (2): 1200–1201.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Ledderhose G (1878-9). "Über Chitin und seine Spaltungs-produkte". Zeitschrift für physiologische Chemie. ii: 213–227.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Ledderhose G (1880). "Über Glykosamin". Zeitschrift für physiologische Chemie. iv: 139–159.

- W. N. Haworth, W. H. G. Lake, S. Peat (1939). "The configuration of glucosamine (chitosamine)". Journal of the Chemical Society: 271–274.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Roseman S (2001). "Reflections on glycobiology". J Biol Chem. 276 (45): 41527–42. doi:10.1074/jbc.R100053200. PMID 11553646.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Ghosh S, Blumenthal HJ, Davidson E, Roseman S (1 May 1960). "Glucosamine metabolism. V. Enzymatic synthesis of glucosamine 6-phosphate". J Biol Chem. 235 (5): 1265–73. PMID 13827775.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "UDP-N-acetylglucosamine Biosynthesis". Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology on the Nomenclature and Classification of Enzymes by the Reactions they Catalyse. International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2002. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ^ Buse MG (2006). "Hexosamines, insulin resistance, and the complications of diabetes: current status". Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 290 (1): E1 – E8. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00329.2005. PMC 1343508. PMID 16339923.

- http://www.fda.gov/Food/DietarySupplements/ConsumerInformation/ucm110417.htm

- "Glucosamine sulfate: Effectiveness". Medline Plus.

- Clinicaltrials.gov

- Clegg DO; Reda DJ; Harris CL; et al. (2006). "Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis". N. Engl. J. Med. 354 (8): 795–808. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052771. PMID 16495392.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Sawitzke AD (2008). "The effect of glucosamine and/or chondroitin sulfate on the progression of knee osteoarthritis: a report from the glucosamine/chondroitin arthritis intervention trial". Arthritis Rheum. 58 (10): 3183–91. PMID 18821708.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Sawitzke AD (2010). "Clinical efficacy and safety of glucosamine, chondroitin sulphate, their combination, celecoxib or placebo taken to treat osteoarthritis of the knee: 2-year results from GAIT". Arthritis Rheum. 69 (8): 1459–64. PMID 20525840.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - PDR Health

- Adams ME (1999). "Hype about glucosamine". Lancet. 354 (9176): 353–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)90040-5. PMID 10437858.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Gulin JP, Felson DT (2000). "Glucosamine and chondroitin for treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic quality assessment and meta-analysis". JAMA : the Journal of the American Medical Association. 283 (11): 1469–75. doi:10.1001/jama.283.11.1469. PMID 10732937.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hughes R, Carr A (2002). "A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of glucosamine sulphate as an analgesic in osteoarthritis of the knee". Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 41 (3): 279–84. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/41.3.279. PMID 11934964.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Cibere J; Kopec JA; Thorne A; et al. (2004). "Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled glucosamine discontinuation trial in knee osteoarthritis". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 51 (5): 738–45. doi:10.1002/art.20697. PMID 15478160.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Vlad SC, LaValley MP, McAlindon TE and Felson DT (2007). "Glucosamine for Pain in Osteoarthritis; Why Do Trial Results Differ?". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 56 (7): 2267–77. doi:10.1002/art.22728. PMID 17599746.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Anastassiades TP; et al. (2005). "Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD002946. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002946.pub2. PMID 15846645.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dahmer S, Schiller RM (2008). "Glucosamine". Am Fam Physician. 78 (4): 471–6. PMID 18756654.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Richy F, Bruyere O, Ethgen O, Cucherat M, Henrotin Y, Reginster JY (2003). "Structural and symptomatic efficacy of glucosamine and chondroitin in knee osteoarthritis: a comprehensive meta-analysis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 163 (13): 1514–22. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.13.1514. PMID 12860572.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wandel S, Jüni P, Tendal B, Nüesch E, Villiger PM, Welton NJ, Trelle S (2010). "Effects of glucosamine, chondroitin, or placebo in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: network meta-analysis" (PDF). British Medical Journal. 341 (sep16 2): c4675. doi:10.1136/bmj.c4675. PMC 2941572. PMID 20847017.

Compared with placebo, glucosamine, chondroitin, and their combination do not reduce joint pain or have an impact on narrowing of joint space

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pearson, W; Lindinger, M (2009). "Low quality of evidence for glucosamine-based nutraceuticals in equine joint disease: Review of in vivo studies". Equine veterinary journal. 41 (7): 706–12. PMID 19927591.

- Lafontaine-Lacasse M, Dore M, Picard, F (2011). "Hexosamines stimulate apoptosis by altering Sirt1 action and levelsin rodent pancreatic β-cells". Journal of Endocrinology. 208 (1): 41–9. doi:10.1677/JOE-10-0243. PMID 20923823.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McFarlane, Gary J. Complementary and alternative medicines for the treatment of reheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia (PDF). ARC. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-1-901815-13-9. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- Gray HC, Hutcheson PS, Slavin RG (2004). "Is glucosamine safe in patients with seafood allergy?". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 114 (2): 459–60. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2004.05.050. PMID 15341031.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - http://dietarysupplements.nlm.nih.gov/dietary/detail.jsp?name=Kirkland+Signature+Extra+Strength+Glucosamine+with+MSM&contain=11001019&pageD=brand

- http://dietarysupplements.nlm.nih.gov/dietary/detail.jsp?name=Whole+Health+Glucosamine+Sulfate+750+mg&contain=23008048&pageD=brand

- http://www.nutraingredients-usa.com/Industry/Another-vegetarian-glucosamine-launched-in-US

- http://www.cosmeticsdesign.com/Market-Trends/New-source-for-glucosamine

- Scroggie DA, Albright A, Harris MD (2003). "The effect of glucosamine-chondroitin supplementation on glycosylated hemoglobin levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a placebo-controlled, double-blinded, randomized clinical trial". Archives of Internal Medicine. 163 (13): 1587–90. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.13.1587. PMID 12860582.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tannis AJ, Barban J, Conquer JA (2004). "Effect of glucosamine supplementation on fasting and non-fasting plasma glucose and serum insulin concentrations in healthy individuals". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 12 (6): 506–11. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2004.03.001. PMID 15135147.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Monauni T; Zenti MG; Cretti A; et al. (2000). "Effects of glucosamine infusion on insulin secretion and insulin action in humans". Diabetes. 49 (6): 926–35. doi:10.2337/diabetes.49.6.926. PMID 10866044.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Anderson JW, Nicolosi RJ, Borzelleca JF (2005). "Glucosamine effects in humans: a review of effects on glucose metabolism, side effects, safety considerations and efficacy". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 43 (2): 187–201. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2004.11.006. PMID 15621331.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (Study financially supported by Cargill Incorporated, a manufacturer of glucosamine as acknowledged in the paper.) - Muniyappa R; Karne RJ; Hall G; et al. (2006). "Oral glucosamine for 6 weeks at standard doses does not cause or worsen insulin resistance or endothelial dysfunction in lean or obese subjects". Diabetes. 55 (11): 3142–50. doi:10.2337/db06-0714. PMID 17065354.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Pouwels MJ, Jacobs JR, Span PN, Lutterman JA, Smits P, Tack CJ (2001). "Short-term glucosamine infusion does not affect insulin sensitivity in humans". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 86 (5): 2099–103. doi:10.1210/jc.86.5.2099. PMID 11344213.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biggee BA, Blinn CM, Nuite M, Silbert JE, McAlindon TE (2007). "Effects of oral glucosamine sulphate on serum glucose and insulin during an oral glucose tolerance test of subjects with osteoarthritis". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 66 (2): 260–2. doi:10.1136/ard.2006.058222. PMC 1798503. PMID 16818461.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Persiani S, Roda E, Rovati LC, Locatelli M, Giacovelli G, Roda A (2005). "Glucosamine oral bioavailability and plasma pharmacokinetics after increasing doses of crystalline glucosamine sulfate in man". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 13 (12): 1041–9. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.009. PMID 16168682.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Persiani S; Rotini R; Trisolino G; et al. (2007). "Synovial and plasma glucosamine concentrations in osteoarthritic patients following oral crystalline glucosamine sulphate at therapeutic dose". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 15 (7): 764–72. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2007.01.019. PMID 17353133.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Cohen MJ, Braun L (2007). Herbs & natural supplements: an evidence-based guide. Marrickville, New South Wales: Elsevier Australia. ISBN 0-7295-3796-X.

- Largo R; Alvarez-Soria MA; Díez-Ortego I; et al. (2003). "Glucosamine inhibits IL-1beta-induced NFkappaB activation in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 11 (4): 290–8. doi:10.1016/S1063-4584(03)00028-1. PMID 12681956.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help). - Chan PS, Caron JP, Orth MW (2006). "Short-term gene expression changes in cartilage explants stimulated with interleukin beta plus glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate". The Journal of Rheumatology. 33 (7): 1329–40. PMID 16821268.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bassleer C, Rovati L, Franchimont P (1998). "Stimulation of proteoglycan production by glucosamine sulfate in chondrocytes isolated from human osteoarthritic articular cartilage in vitro". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 6 (6): 427–34. doi:10.1053/joca.1998.0146. PMID 10343776.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dodge GR, Jimenez SA (2003). "Glucosamine sulfate modulates the levels of aggrecan and matrix metalloproteinase-3 synthesized by cultured human osteoarthritis articular chondrocytes". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 11 (6): 424–32. doi:10.1016/S1063-4584(03)00052-9. PMID 12801482.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Chan PS, Caron JP, Orth MW (2005). "Effect of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate on regulation of gene expression of proteolytic enzymes and their inhibitors in interleukin-1-challenged bovine articular cartilage explants". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 66 (11): 1870–6. doi:10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.1870. PMID 16334942.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Uitterlinden EJ; Jahr H; Koevoet JL; et al. (2006). "Glucosamine decreases expression of anabolic and catabolic genes in human osteoarthritic cartilage explants". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 14 (3): 250–7. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2005.10.001. PMID 16300972.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Chu SC; Yang SF; Lue KH; et al. (2006). "Glucosamine sulfate suppresses the expressions of urokinase plasminogen activator and inhibitor and gelatinases during the early stage of osteoarthritis". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 372 (1–2): 167–72. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2006.04.014. PMID 16756968.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Swarbrick J, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of Pharmaceutical Technology. Vol. 4 (Third ed.). Informa Healthcare. p. 2436. ISBN 978-0-8493-9399-0.

- "Dietary Supplements". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- "Effects of Oral Glucosamine on Insulin and Blood Vessel Activity in Normal and Obese People". ClinicalTrials.gov. June 23, 2006. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ Jordan KM; Arden NK; Doherty M; et al. (2003). "EULAR Recommendations 2003: a evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: Report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT)". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 62 (12): 1145–55. doi:10.1136/ard.2003.011742. PMC 1754382. PMID 14644851.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Zhang W; Moskowitz RW; Nuki G; et al. (2007). "OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 15 (9): 981–1000. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2007.06.014. PMID 17719803.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Glucosamine article, Mayo Clinic

- General glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate information from the Arthritis Foundation.

- "UDP-N-acetylglucosamine biosynthesis," diagram including IUBMB nomenclature and links.

- PDR Health Summary of drug information on glucosamine from the publishers of the Physician's Desk Reference.

- "Glucosamine and chondroitin for arthritis: Benefit is unlikely," Summary of and commentary on research findings, including GAIT clinical trial.

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (primarily M01A and M02A, also N02BA) | |

|---|---|

| pyrazolones / pyrazolidines | |

| salicylates | |

| acetic acid derivatives and related substances | |

| oxicams | |

| propionic acid derivatives (profens) |

|

| n-arylanthranilic acids (fenamates) | |

| COX-2 inhibitors (coxibs) | |

| other | |

| NSAID combinations | |

| Key: underline indicates initially developed first-in-class compound of specific group; WHO-Essential Medicines; withdrawn drugs; veterinary use. | |