| Revision as of 23:03, 14 May 2024 editDavemck (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users120,696 editsm Clean up duplicate template arguments using findargdups← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:26, 15 May 2024 edit undoArkHyena (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,342 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

| == Mechanisms == | == Mechanisms == | ||

| A major challenge in models of cryovolcanic mechanisms is that liquid water is substantially denser than water ice, in contrast to ]s where liquid magma is less dense than solid rock. As such, cryomagma must overcome this in order to erupt onto a body's surface. |

A major challenge in models of cryovolcanic mechanisms is that liquid water is substantially denser than water ice, in contrast to ]s where liquid magma is less dense than solid rock. As such, cryomagma must overcome this in order to erupt onto a body's surface. A variety of hypotheses have been proposed by planetary scientists to explain how cryomagma erupts onto the surface. | ||

| The ] of compounds more volatile than water or the inclusion of various compounds can help lower the density of the cryomagma, allowing it to ascend. Alternatively, impurities in the ice shell can increase its density.<ref name="gregg2021"/>{{rp|page=180–182}} Alternatively, the progressive pressurization of a subsurface ocean as it cools and freezes may be enough to drive cryomagma to ascend to the surface due to water's unusual property of expanding upon freezing. Internal ocean pressurization does not necessitate the addition of other volatile compounds.<ref name="manga2007"/><ref name="gregg2021"/>{{rp|page=183}} | |||

| === Reservoirs === | |||

| === Cryomagma reservoirs === | |||

| The most common reservoir of cryomagma is subsurface oceans.<ref name="gregg2021"/>{{rp|page=167}} Subsurface oceans are widespread amongst the satellites of the ]s and are largely maintained by ].<ref name="ucsc.2008"/> Evidence for subsurface oceans also exist on the dwarf planets ]<ref name="mcogvern2024"/> and, to a lesser extent, ].<ref name="mccord.2005"/><ref name="cr.ceres"/> Fractures in the ice shell, caused by stresses from diurnal tides, ice shell libration, internal expansion or contraction, or other sources of stress, can form direct conduits from which cryomagma may ascend from.<ref name="gregg2021"/>{{rp|page=185}} | The most common reservoir of cryomagma is subsurface oceans.<ref name="gregg2021"/>{{rp|page=167}} Subsurface oceans are widespread amongst the satellites of the ]s and are largely maintained by ].<ref name="ucsc.2008"/> Evidence for subsurface oceans also exist on the dwarf planets ]<ref name="mcogvern2024"/> and, to a lesser extent, ].<ref name="mccord.2005"/><ref name="cr.ceres"/> Fractures in the ice shell, caused by stresses from diurnal tides, ice shell libration, internal expansion or contraction, or other sources of stress, can form direct conduits from which cryomagma may ascend from.<ref name="gregg2021"/>{{rp|page=185}} | ||

| Line 62: | Line 64: | ||

| == Observations == | == Observations == | ||

| Although there are broad parallels between cryovolcanism and terrestrial (or "silicate") volcanism, such as the construction of domes and shields, the definitive identification of cryovolcanic structures is difficult. The unusual properties of water-dominated cryolava, for example, means that cryovolcanic features are difficult to interpret using criteria applied to terrestrial volcanic features.<ref name="gregg2021"/>{{rp|page=162}}<ref name="PlanetaryLandforms"/>{{rp|487}} | |||

| === Ceres === | === Ceres === | ||

Revision as of 00:26, 15 May 2024

Type of volcano that erupts volatiles such as water, ammonia or methane, instead of molten rock For ice mounds on Earth, see Ice volcano.

A cryovolcano (sometimes informally referred to as an ice volcano) is a type of volcano that erupts gases and volatile material such as liquid water, ammonia, and hydrocarbons. The erupted material is collectively referred to as cryolava; it originates from a reservoir of subsurface cryomagma. Cryovolcanic eruptions can take many forms, such as fissure and curtain eruptions, effusive cryolava flows, and large-scale resurfacing, and can vary greatly in output volumes. Immediately after an eruption, cryolava quickly freezes, constructing geological features and altering the surface.

Although rare in the inner Solar System, past and recent cryovolcanism is common on planetary objects in the outer Solar System, especially on the icy moons of the giant planets and potentially amongst the dwarf planets as well. As such, cryovolcanism is important to the geological histories of these worlds. Despite this, only a few eruptions have ever been observed in the Solar System. The sporadic nature of direct observations means that the true number of extant cryovolcanoes is contentious.

Like volcanism on the terrestrial planets, cryovolcanism is driven by escaping internal heat, often supplied by extensive tidal heating in the case of the moons of the giant planets. However, isolated dwarf planets are capable of retaining enough internal heat from formation and radioactive decay to drive cryovolcanism on their own, an observation which has been supported by both in situ and distant observations.

Etymology and terminology

The term cryovolcano was coined by Steven K. Croft in a 1987 conference abstract at the Geological Society of America Abstract with Programs. The term is ultimately a combination of cryo-, from the Ancient Greek κρῠ́ος (krúos, meaning cold or frost), and volcano. Broadly, terminology used to describe cryovolcanism is analogous to volcanic terminology:

- Cryolava and cryomagma are distinguished in a manner similar to lava and magma. Cryomagma refers to the molten or partially molten material beneath a body's surface, where it may then erupt onto the surface. If the material is still fluid, it is classified as cryolava, which can flow in cryolava flows, analogs to lava flows. Explosive eruptions, however, may pulverize the material into an "ash" termed cryoclastic material. Cryoclastic material flowing downhill produces cryoclastic flows, analogs to pyroclastic flows.

- A cryovolcanic edifice is a landform constructed by cryovolcanic eruptions. These may take the form of shields (analogous to terrestrial shield volcanoes), cones (analogous to cinder cones and spatter cones), or domes (analogous to lava domes). Cryovolcanic edifices may support subsidiary landforms, such as caldera-like structures, cryovolcanic flow channels (analogous to lava flow features), and cryovolcanic fields and plains (analogous to lava fields and plains).

As cryovolcanism largely takes place on icy worlds, the term ice volcano is sometimes used colloquially.

Types of cryovolcanism

Explosive eruptions

Explosive cryovolcanism, or cryoclastic eruptions, is expected to be driven by the exsolvation of dissolved volatile gasses as pressure drops whilst cryomagma ascends, much like the mechanisms of explosive volcanism on terrestrial planets. Whereas terrestrial explosive volcanism is primarily driven by dissolved water (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), and sulfur dioxide (SO2), explosive cryovolcanism may instead be driven by methane and carbon monoxide. Upon eruption, cryovolcanic material is pulverized in violent explosions much like volcanic ash and tephra, producing cryoclastic material.

Effusive eruptions

Effusive cryovolcanism takes place with little to no explosive activity and is instead characterized by widespread cryolava flows which cover the pre-existing landscape. In contrast to explosive cryovolcanism, no instances of active effusive cryovolcanism have been observed. Structures constructed by effusive eruptions depend on the viscosity of the erupted material. Eruptions of less viscous cryolava can resurface large regions and form expansive, relatively flat plains, similar to shield volcanoes and flood basalt eruptions on terrestrial planets. More viscous erupted material does not travel as far, and instead can construct localized high-relief cryovolcanic domes.

Mechanisms

A major challenge in models of cryovolcanic mechanisms is that liquid water is substantially denser than water ice, in contrast to silicates where liquid magma is less dense than solid rock. As such, cryomagma must overcome this in order to erupt onto a body's surface. A variety of hypotheses have been proposed by planetary scientists to explain how cryomagma erupts onto the surface.

The exsolvation of compounds more volatile than water or the inclusion of various compounds can help lower the density of the cryomagma, allowing it to ascend. Alternatively, impurities in the ice shell can increase its density. Alternatively, the progressive pressurization of a subsurface ocean as it cools and freezes may be enough to drive cryomagma to ascend to the surface due to water's unusual property of expanding upon freezing. Internal ocean pressurization does not necessitate the addition of other volatile compounds.

Cryomagma reservoirs

The most common reservoir of cryomagma is subsurface oceans. Subsurface oceans are widespread amongst the satellites of the giant planets and are largely maintained by tidal heating. Evidence for subsurface oceans also exist on the dwarf planets Pluto and, to a lesser extent, Ceres. Fractures in the ice shell, caused by stresses from diurnal tides, ice shell libration, internal expansion or contraction, or other sources of stress, can form direct conduits from which cryomagma may ascend from.

In an alternative hypothesis, material instead upwells through solid convection or density differences within the ice shell, ascending without the need for fractures or a subsurface ocean. The material may then melt into subsurface pockets of cryomagma due to warm ice transferring heat to impure, lower melting point ice, which may then erupt or form diapirs.

Composition

Water is expected to be the dominant component of cryomagmas. Besides water, cryomagma may contain additional impurities, drastically changing its properties. Certain compounds can lower the density of cryomagma. Ammonia (NH3) in particular may be a common component of cryomagmas, and has been detected in the plumes of Saturn's moon Enceladus. A partially frozen Ammonia-water eutectic mixture can be positively buoyant with respect to the icy crust, enabling its eruption. Methanol (CH3OH) can lower cryomagma density even further, whilst significantly increasing viscosity. Conversely, some impurities can increase the density of cryomagma. Salts, such as magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) and sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) significantly increases density with comparatively minor changes in viscosity. Salty or briny cryomagma compositions may be important cryovolcanism on Jupiter's icy moons, where salt-dominated impurities are likely more common.

| Cryomagma composition, mass % | Melting point (K) | Liquid density (g/cm) | Liquid viscosity (Pa·s) | Solid density (g/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure water 100% H2O |

273 | 1.000 | 0.0017 | 0.917 |

| Brine 81.2% H2O, 16% MgSO4, 2.8% Na2SO4 |

268 | 1.19 | 0.007 | 1.13 |

| Ammonia and water 67.4% H2O, 32.6% NH3 |

176 | 0.946 | 4 | 0.962 |

| Ammonia, water, and methanol 47% H2O, 23% NH3, 30% CH3OH |

153 | 0.978 | 4,000 | – |

| Nitrogen and methane 86.5% N2, 13.5% CH4 |

62 | 0.783 | 0.0003 | – |

| Basaltic lava (comparison) | – | – | ~10-100 | – |

Observations

Although there are broad parallels between cryovolcanism and terrestrial (or "silicate") volcanism, such as the construction of domes and shields, the definitive identification of cryovolcanic structures is difficult. The unusual properties of water-dominated cryolava, for example, means that cryovolcanic features are difficult to interpret using criteria applied to terrestrial volcanic features.

Ceres

Main article: Ceres (dwarf planet) § CryovolcanismCeres remains the innermost cryovolcanically active body in the Solar System. Upon the arrival of the Dawn orbiter in March 2015, the dwarf planet was discovered to have numerous bright spots (designated as faculae) located within several major impact basins, most prominently in the center of Occator Crater. These bright spots are composed primarily of various salts, and have been hypothesized to have formed from impact-induced upwelling of subsurface material and may indicate that Ceres had a subsurface ocean in its past. Dawn also discovered Ahuna Mons and Yamor Mons (formerly Ysolos Mons), two prominent isolated mountains which are hypothesized to be young cryovolcanic domes. It is expected that cryovolcanic domes eventually subside after becoming extinct due to viscous relaxation, flattening them. This would explain why Ahuna Mons appears to be the most prominent construct on Ceres, despite its geologically young age.

Europa

Main article: Europa (moon) § Surface featuresEuropa receives enough tidal heating from Jupiter to sustain a global liquid water ocean. Its surface is exceedingly young, at roughly 60 to 90 million years old. Its most striking features, a dense web of linear cracks and faults termed lineae, appear to be the sites of active resurfacing on Europa, proceeding in a manner similar to Earth's mid-ocean ridges. In addition to this, Europa may experience a form of subduction, with one block of its icy crust sliding underneath another.

Despite its young surface age, few, if any, distinct cryovolcanoes have been definitively identified on the Europan surface in the past. Nevertheless, observations of Europa from the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) in December 2012 detected columns of excess water vapor up to 200 kilometres (120 miles) high, hinting at the existence of weak, possibly cryovolcanic plumes. The plumes were observed again by the HST in 2014. However, as these are distant observations, the plumes have yet to be definitively confirmed. Recent analyses of some Europan surface features have proposed cryovolcanic origins for them as well. In 2011, Europa's chaos terrain, where the crust appears especially disrupted, was interpreted as the site of very shallow cryomagma lakes. As these subsurface lakes melt and refreeze, they fracture Europa's crust into small blocks, creating the chaos terrain. Later, in 2023, a field of cryovolcanic cones was tentatively identified near the western edge of Argadnel Regio, a region in Europa's southern hemisphere.

Ganymede

Ganymede's surface, like Europa's, is heavily tectonized yet appears to have few cryovolcanic features. Ganymede's surface has several irregularly-shaped depressions (termed paterae) which have been identified as candidate cryovolcanic calderas.

Enceladus

Main article: Enceladus § South polar plumes

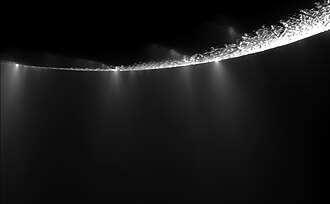

Saturn's moon Enceladus is host to the most dramatic example of cryovolcanism yet observed, with a series of vents erupting 250 kg of material per second that feeds Saturn's E ring. These eruptions take place across Enceladus's south polar region, sourced from four major ridges which form a region informally known as the Tiger Stripes. Enceladus's cryovolcanic activity is sustained by a global subsurface ocean.

Other regions of Enceladus exhibit similar terrain to that of the Tiger Stripes, possibly indicating that Enceladus has experienced discrete periods of heightened cryovolcanism in the past.

Titan

Main article: Titan (moon) § Cryovolcanism and mountainsSaturn's moon Titan has a dense atmospheric haze layer which permanently obscures visible observations of its surface features, making the definitive identification of cryovolcanic structures especially difficult. Titan has an extensive subsurface ocean, encouraging searches for cryovolcanic features, and several features have been proposed as candidate cryovolcanoes, most notably Doom Mons. Lakes and depressions in Titan's polar regions show morphological evidence of an explosive origin, leading to a hypothesis that they form from maar-like eruptions.

Uranian moons

Of Uranus's five major satellites, Miranda and Ariel appear to have unusually youthful surfaces indicative of relatively recent activity. Miranda in particular has extraordinarily varied terrain, with striking angular features known as the coronae cutting across older terrain. Inverness Corona is located near Miranda's south pole and is estimated to be less than 1 billion years old, and broad similarities between Miranda's coronae and Enceladus's south polar region have been noted. These characteristics have led to hypotheses that propose a cryovolcanic origin of the coronae, where eruptions of viscous cryomagma form the structures. Ariel also exhibits widespread resurfacing, with large polygonal crustal blocks divided by large canyons (chasmata) with floors as young as ~0.8 ± 0.5 billion years old, while relatively flat plains may have been the site of large flood eruptions.

Evidence for relatively recent cryovolcanism on the other three round moons of Uranus is less clear. Titania hosts large grabens, and Oberon has a massive ~11 km (6.8 mi) high mountain observed on its limb; the precise origins of the mountain is unclear, but a cryovolcanic origin has been proposed.

Triton

Main article: Geology of Triton § CryovolcanismWith an estimated average surface age of 10–100 million years old, with some regions possibly being only a few million years old, Triton is one of the most geologically active worlds in the Solar System. Large-scale cryovolcanic landforms have been identified on Triton's young surface, including Leviathan Patera, the apparent primary vent of the Cipango Planum cryovolcanic plateau which is one of the largest volcanic or cryovolcanic edifices in the Solar System.

Triton hosts four walled plains: Ruach Planitia and Tuonela Planitia form a northern pair, and Sipapu Planitia and Ryugu Planitia form a southern pair. The walled plains are characterized by crenulated cliffs that enclose a flat, young surface with a single group of pits and mounds. The walled plains have been hypothesized as young cryovolcanic lakes and may represent Triton's youngest cryovolcanic features. The regions around Ruach and Tuonela feature additional smaller subcircular depressions, some of which are partially bordered by walls and scarps. These depressions have been interpreted as diapirs, explosive craters, caldera-like structures, or impact craters filled in by cryolava flows. To the south of Tuonela Planitia, isolated conical hills with central depressions have been noted as resembling terrestrial cinder cones, possibly pointing to cryovolcanic activity beyond Tuonela Planitia's plains.

Triton's southern polar ice cap is marked by a multitude of dark streaks, likely composed of organic tholins deposited by wind-blown plumes. At least two plumes, the Mahilani Plume and the Hili Plume, have been observed, with the two plumes reaching 8 kilometres (5.0 miles) in altitude. These plumes have been hypothesized to be driven by subsurface sublimation of nitrogen ice under prolonged exposure to sunlight in the southern hemispheric summer; however, it has alternatively been proposed that the plume streaks may alternatively represent fallout from cryovolcanic eruptions.

Pluto and Charon

Main articles: Geology of Pluto and Geology of Charon

The surface of the dwarf planet Pluto varies dramatically in age, and several regions appear to display relatively recent cryovolcanic activity. The most reliably identified cryovolcanic structures are Wright Mons and Piccard Mons, two large mountains with central depressions which have led to hypotheses that they may be cryovolcanoes with peak calderas. The two mountains are surrounded by an unusual region of hilly "hummocky terrain", and the lack of distinct flow features have led to alternative proposals that the structures may instead be formed by sequential dome-forming eruptions, with nearby Coleman Mons being a smaller independent dome.

Virgil Fossae, a large fault within Belton Regio, may also represent another site of cryovolcanism on Pluto. Large flows radiate away from Virgil Fossae and appear to have partially erased preceding terrain, with several nearby craters being partly infilled by material. More recently, Hekla Cavus was hypothesized to have formed from a cryovolcanic collapse. Similarly, Kiladze Crater has been proposed as a caldera formed from a voluminous eruption.

Although Sputnik Planitia represents the youngest surface on Pluto, it is not a cryovolcanic structure; Sputnik Planitia continuously resurfaces itself with the convective overturning of glacial nitrogen ice, fuelled by Pluto's internal heat and sublimation into Pluto's atmosphere.

Charon's surface dichotomy indicates that a large section of its surface may have been flooded in large, effusive eruptions, similar to the Lunar maria. These floodplains form Vulcan Planitia and may have erupted as Charon's internal ocean froze.

Other dwarf planets

In 2022, low-resolution near-infrared (0.7–5 μm) spectroscopic observations by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) detected light hydrocarbons and complex organic molecules on the surfaces of the dwarf planets Quaoar, Gonggong, and Sedna. The detection indicated that all three have experienced internal melting and planetary differentiation in their pasts. The presence of volatiles on their surfaces indicates that cryovolcanism may be resupplying methane. JWST spectral observations of Eris and Makemake revealed that hydrogen-deuterium and carbon isotopic ratios indicated that both dwarf planets are actively replenishing surface methane as well, probably with the presence of a subsurface ocean.

Gallery

Various examples of probable cryovolcanic structures in the Solar System-

Ruach Planitia and Tuonela Planitia, Triton

Ruach Planitia and Tuonela Planitia, Triton

-

Detail mosaic of Leviathan Patera, Triton

Detail mosaic of Leviathan Patera, Triton

-

Radar image of Doom Mons, Titan

Radar image of Doom Mons, Titan

-

Ahuna Mons, Ceres

Ahuna Mons, Ceres

-

Topography map of Wright Mons and Piccard Mons, Pluto

Topography map of Wright Mons and Piccard Mons, Pluto

-

Dome in Murias Chaos, Europa

Dome in Murias Chaos, Europa

-

Elsinore Corona, Miranda

-

Inverness Corona, Miranda

Inverness Corona, Miranda

-

Plumes of Enceladus

Plumes of Enceladus

-

Enceladus feeding the E ring

Enceladus feeding the E ring

See also

- List of extraterrestrial volcanoes

- Extraterrestrial liquid water – Liquid water naturally occurring outside Earth

- Planetary oceanography – Study of extraterrestrial oceans

- Ice volcano – Wave-driven mound of ice formed on terrestrial lakes

- Frazil ice – Collections of ice crystals in open water

- Pingo – Mound of earth-covered ice

Notes

- Using an estimated surface area of at least 490,000 km for Cipango Planum, this significantly surpasses Olympus Mons's area of roughly 300,000 km. As Cipango Planum extended beyond Triton's terminator during Voyager 2's closest approach, its true extent is uncertain and may be significantly larger

References

- Witze, Alexandra (2015). "Ice volcanoes may dot Pluto's surface". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18756. S2CID 182698872.

- ^ Emery, J. P.; Wong, I.; Brunetto, R.; Cook, R.; Pinilla-Alonso, N.; Stansberry, J. A.; et al. (March 2024). "A Tale of 3 Dwarf Planets: Ices and Organics on Sedna, Gonggong, and Quaoar from JWST Spectroscopy". Icarus. 414 (116017). arXiv:2309.15230. Bibcode:2024Icar..41416017E. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2024.116017.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "κρύος". A Greek–English Lexicon. Clarendon Press.

- ^ Hargitai, Henrik; Kereszturi, Ákos, eds. (2015). Encyclopedia of Planetary Landforms (first ed.). Springer New York. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3134-3. ISBN 978-1-4614-3133-6.

- ^ Gregg, Tracy K. P.; Lopes, Rosaly M. C.; Fagents, Sarah A. (December 2021). Planetary Volcanism across the Solar System. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-813987-5.00005-5. ISBN 978-0-12-813987-5. S2CID 245084572. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Geissler, Paul (2015). The Encyclopedia of Volcanoes (Second ed.). pp. 763–776. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385938-9.00044-4. ISBN 978-0-12-385938-9. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- Fortes, A. D.; Gindrod, P. M.; Trickett, S. K.; Vočadlo, L. (May 2007). "Ammonium sulfate on Titan: Possible origin and role in cryovolcanism". Icarus. 188 (1): 139–153. Bibcode:2007Icar..188..139F. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.11.002.

- ^ Croft, S. K.; Kargel, J. S.; Kirk, R. L.; et al. (1995). "The geology of Triton". Neptune and Triton: 879–947. Bibcode:1995netr.conf..879C.

- Schenk, P. M.; Beyer, R. A.; McKinnon, W. B.; Moore, J. M.; Spencer, J. R.; White, O. L.; Singer, K.; Nimmo, F.; Thomason, C.; Lauer, T. R.; Robbins, S.; Umurhan, O. M.; Grundy, W. M.; Stern, S. A.; Weaver, H. A.; Young, L. A.; Smith, K. E.; Olkin, C. (November 2018). "Basins, fractures and volcanoes: Global cartography and topography of Pluto from New Horizons". Icarus. 314: 400–433. Bibcode:2018Icar..314..400S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.06.008. S2CID 126273376.

- Sohn, Rebecca (1 April 2022). "Ice volcanoes on Pluto may still be erupting". Space.com.

- ^ Manga, M.; Wang, C. -Y. (April 2007). "Pressurized oceans and the eruption of liquid water on Europa and Enceladus". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (7). Bibcode:2007GeoRL..34.7202M. doi:10.1029/2007GL029297. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- "Tidal heating and the long-term stability of a subsurface ocean on Enceladus" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- McGovern, J. C.; Nguyen, A. L. (April 2024). "The role of Pluto's ocean's salinity in supporting nitrogen ice loads within the Sputnik Planitia basin". Icarus. 412. Bibcode:2024Icar..41215968M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2024.115968. S2CID 267316007. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- McCord, Thomas B. (2005). "Ceres: Evolution and current state". Journal of Geophysical Research. 110 (E5): E05009. Bibcode:2005JGRE..110.5009M. doi:10.1029/2004JE002244.

- Castillo-Rogez, J. C.; McCord, T. B.; Davis, A. G. (2007). "Ceres: evolution and present state" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science. XXXVIII: 2006–2007. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- Kargel, J. S. (1995). "Cryovolcanism on the Icy Satellites". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 67 (1–3): 101–113. Bibcode:1995EM&P...67..101K. doi:10.1007/BF00613296. S2CID 54843498. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- Philpotts, Anthony R.; Ague, Jay J. (2009). Principles of igneous and metamorphic petrology (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 53–55. ISBN 9780521880060.

- Landau, Elizabeth; Brown, Dwayne (6 March 2015). "NASA Spacecraft Becomes First to Orbit a Dwarf Planet". NASA. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- De Sanctis, M; Ammannito, E; Raponi, A; Frigeri, A; Ferrari, M; Carrozzo, F; Ciarniello, M; Formisano, M; Rousseau, B; Tosi, F.; Zambon, F.; Raymond, C. A.; Russell, C. T. (10 August 2020). "Fresh emplacement of hydrated sodium chloride on Ceres from ascending salty fluids". Nature Astronomy. 4 (8): 786–93. Bibcode:2020NatAs...4..786D. doi:10.1038/s41550-020-1138-8. S2CID 225442620.

- ^ Sori, Michael T.; Sizemore, Hanna G.; et al. (December 2018). "Cryovolcanic rates on Ceres revealed by topography". Nature Astronomy. 2 (12): 946–950. Bibcode:2018NatAs...2..946S. doi:10.1038/s41550-018-0574-1. S2CID 186800298. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- Schenk, Paul M.; Chapman, Clark R.; Zahnle, Kevin; and Moore, Jeffrey M. (2004) "Chapter 18: Ages and Interiors: the Cratering Record of the Galilean Satellites" Archived 24 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 427 ff. in Bagenal, Fran; Dowling, Timothy E.; and McKinnon, William B., editors; Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-81808-7.

- ^ Kattenhorn, Simon A. (March 2018). "Commentary: The Feasibility of Subduction and Implications for Plate Tectonics on Jupiter's Moon Europa". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 123 (3): 684–689. Bibcode:2018JGRE..123..684K. doi:10.1002/2018JE005524.

- Figueredo, Patricio H.; Greeley, Ronald (February 2004). "Resurfacing history of Europa from pole-to-pole geological mapping". Icarus. 167 (2): 287–312. Bibcode:2004Icar..167..287F. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2003.09.016.

- Fletcher, Leigh (12 December 2013). "The Plumes of Europa". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- "NASA's Hubble Spots Possible Water Plumes Erupting on Jupiter's Moon Europa". NASA. 26 September 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- Schmidt, Britney; Blankenship, Don; Patterson, Wes; Schenk, Paul (24 November 2011). "Active formation of 'chaos terrain' over shallow subsurface water on Europa". Nature. 479 (7374): 502–505. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..502S. doi:10.1038/nature10608. PMID 22089135. S2CID 4405195.

- Bradák, Balázs; Kereszturi, Ákos; Gomez, Christopher (November 2023). "Tectonic analysis of a newly identified putative cryovolcanic field on Europa". Advances in Space Research. 72 (9): 4064–4073. Bibcode:2023AdSpR..72.4064B. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2023.07.062. S2CID 260798414.

- "Argadnel Regio". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program. (Center Latitude: -14.60°, Center Longitude: 208.50°)

- Showman, Adam P.; Malhotra, Renu (1 October 1999). "The Galilean Satellites" (PDF). Science. 286 (5437): 77–84. doi:10.1126/science.286.5437.77. PMID 10506564. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- Solomonidou, Anezina; Malaska, Michael; Stephan, Katrin; Soderlund, Krista; Valenti, Martin; Lucchetti, Alice; Kalousova, Klara; Lopes, Rosaly (September 2022). Ganymede paterae: a priority target for JUICE. 16th Europlanet Science Congress 2022. Palacio de Congresos de Granada, Spain and online. doi:10.5194/epsc2022-423.

- "Enceladus rains water onto Saturn". ESA. 2011. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Spahn, F.; et al. (10 March 2006). "Cassini Dust Measurements at Enceladus and Implications for the Origin of the E Ring". Science. 311 (5766): 1416–8. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1416S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.466.6748. doi:10.1126/science.1121375. PMID 16527969. S2CID 33554377.

- Porco, C. C.; Helfenstein, P.; Thomas, P. C.; Ingersoll, A. P.; Wisdom, J.; West, R.; Neukum, G.; Denk, T.; Wagner, R. (10 March 2006). "Cassini Observes the Active South Pole of Enceladus". Science. 311 (5766): 1393–1401. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1393P. doi:10.1126/science.1123013. PMID 16527964. S2CID 6976648.

- ^ Thomas, P. C.; Tajeddine, R.; et al. (2016). "Enceladus's measured physical libration requires a global subsurface ocean". Icarus. 264: 37–47. arXiv:1509.07555. Bibcode:2016Icar..264...37T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.08.037. S2CID 118429372.

- Berne, A.; Simons, M.; Keane, J.T.; Leonard, E.J.; Park, R.S. (29 April 2024). "Jet activity on Enceladus linked to tidally driven strike-slip motion along tiger stripes". Nature Geoscience: 1–7. doi:10.1038/s41561-024-01418-0. ISSN 1752-0908.

- Iess, L.; Jacobson, R. A.; Ducci, M.; Stevenson, D. J.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Armstrong, J. W.; Asmar, S. W.; Racioppa, P.; Rappaport, N. J.; Tortora, P. (2012). "The Tides of Titan". Science. 337 (6093): 457–9. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..457I. doi:10.1126/science.1219631. hdl:11573/477190. PMID 22745254. S2CID 10966007.

- Lopes, R. M. C.; Kirk, R. L.; Mitchell, K. L.; LeGall, A.; Barnes, J. W.; Hayes, A.; Kargel, J.; Wye, L.; Radebaugh, J.; Stofan, E. R.; Janssen, M. A.; Neish, C. D.; Wall, S. D.; Wood, C. A.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Malaska, M. J. (19 March 2013). "Cryovolcanism on Titan: New results from Cassini RADAR and VIMS" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 118 (3): 416–435. Bibcode:2013JGRE..118..416L. doi:10.1002/jgre.20062.

- Wood, C.A.; Radebaugh, J. (2020). "Morphologic Evidence for Volcanic Craters near Titan's North Polar Region". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 125 (8): e06036. Bibcode:2020JGRE..12506036W. doi:10.1029/2019JE006036. S2CID 225752345.

- Leonard, Erin Janelle; Beddingfield, Chloe B.; Elder, Catherine M.; Nordheim, Tom Andrei (December 2022). The Geologic History of Miranda's Inverness Corona. AGU Fall Meeting 2022. Chicago, Illinoise. Bibcode:2022AGUFM.P32E1872L.

- ^ Schenk, Paul M.; Moore, Jeffrey M. (December 2020). "Topography and geology of Uranian mid-sized icy satellites in comparison with Saturnian and Plutonian satellites". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 378 (2187). Bibcode:2020RSPTA.37800102S. doi:10.1098/rsta.2020.0102. PMID 33161858.

- Schenk, Paul M.; Zahnle, Kevin (December 2007). "On the negligible surface age of Triton". Icarus. 192 (1): 135–149. Bibcode:2007Icar..192..135S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.07.004.

- Martin-Herrero, Alvaro; Romeo, Ignacio; Ruiz, Javier (2018). "Heat flow in Triton: Implications for heat sources powering recent geologic activity". Planetary and Space Science. 160: 19–25. Bibcode:2018P&SS..160...19M. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2018.03.010. S2CID 125508759.

- ^ Schenk, Paul; Beddingfield, Chloe; Bertrand, Tanguy; et al. (September 2021). "Triton: Topography and Geology of a Probable Ocean World with Comparison to Pluto and Charon". Remote Sensing. 13 (17): 3476. Bibcode:2021RemS...13.3476S. doi:10.3390/rs13173476.

- Frankel, C.S. (2005). Worlds on Fire: Volcanoes on the Earth, the Moon, Mars, Venus and Io; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, p. 132. ISBN 978-0-521-80393-9.

- ^ Sulcanese, Davide; Cioria, Camilla; Kokin, Osip; Mitri, Giuseppe; Pondrelli, Monica; Chiarolanza, Giancula (March 2023). "Geological analysis of Monad Regio, Triton: Possible evidence of endogenic and exogenic processes". Icarus. 392. Bibcode:2023Icar..39215368S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2022.115368. S2CID 254173536. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ McKinnon, William B.; Kirk, Randolph L. (2014). Encyclopedia of the Solar System (Third ed.). pp. 861–881. doi:10.1016/C2010-0-67309-3. ISBN 978-0-12-415845-0. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- Martin-Herrero, A.; Ruiz, J.; Romeo, I. (March 2014). Characterization and Possible Origin of Sub-Circular Depressions in Ruach Planitia Region, Triton (PDF). 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. The Woodlands, Texas. Bibcode:2014LPI....45.1177M.

- Hofgartner, Jason D.; Birch, Samuel P. D.; Castillo, Julie; Grundy, Will M.; Hansen, Candice J.; Hayes, Alexander G.; Howett, Carly J. A.; Hurford, Terry A.; Martin, Emily S.; Mitchell, Karl L.; Nordheim, Tom A.; Poston, Michael J.; Prockter, Louise M.; Quick, Lynnae C.; Schenk, Paul (15 March 2022). "Hypotheses for Triton's plumes: New analyses and future remote sensing tests". Icarus. 375: 114835. arXiv:2112.04627. Bibcode:2022Icar..37514835H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2021.114835. ISSN 0019-1035.

- "At Pluto, New Horizons Finds Geology of All Ages, Possible Ice Volcanoes, Insight into Planetary Origins". New Horizons News Center. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory LLC. 9 November 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Witze, A. (9 November 2015). "Icy volcanoes may dot Pluto's surface". Nature. Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18756. S2CID 182698872. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Singer, Kelsi N. (29 March 2022). "Large-scale cryovolcanic resurfacing on Pluto". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 1542. arXiv:2207.06557. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.1542S. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-29056-3. PMC 8964750. PMID 35351895.

- Cruikshank, Dale P.; Umurhan, Orkan M.; Beyer, Ross A.; Schmitt, Bernard; Keane, James T.; Runyon, Kirby D.; Atri, Dimitra; White, Oliver L.; Matsuyama, Isamu; Moore, Jeffrey M.; McKinnon, William B.; Sandford, Scott A.; Singer, Kelsi N.; Grundy, William M.; Dalle Ore, Cristina M.; Cook, Jason C.; Bertrand, Tanguy; Stern, S. Alan; Olkin, Catherine B.; Weaver, Harold A.; Young, Leslie A.; Spencer, John R.; Lisse, Carey M.; Binzel, Richard P.; Earle, Alissa M.; Robbins, Stuart J.; Gladstone, G. Randall; Cartwright, Richard J.; Ennico, Kimberly (15 September 2019). "Recent cryovolcanism in Virgil Fossae on Pluto". Icarus. 330: 155–168. Bibcode:2019Icar..330..155C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.04.023. S2CID 149983734.

- Ahrens, C. J.; Chevrier, V. F. (March 2021). "Investigation of the morphology and interpretation of Hekla Cavus, Pluto". Icarus. 356. Bibcode:2021Icar..35614108A. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114108.

- Emran, A.; Dalle Ore, C. M.; Cruikshank, D. P.; Cook, J. C. (March 2021). "Surface composition of Pluto's Kiladze area and relationship to cryovolcanism". Icarus. 404. arXiv:2303.17072. Bibcode:2023Icar..40415653E. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115653.

- McKinnon, W. B.; et al. (1 June 2016). "Convection in a volatile nitrogen-ice-rich layer drives Pluto's geological vigour". Nature. 534 (7605): 82–85. arXiv:1903.05571. Bibcode:2016Natur.534...82M. doi:10.1038/nature18289. PMID 27251279. S2CID 30903520.

- Desch, S. J.; Neveu, M. (2017). "Differentiation and cryovolcanism on Charon: A view before and after New Horizons". Icarus. 287: 175–186. Bibcode:2017Icar..287..175D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.11.037.

- Glein, Christopher R.; Grundy, William M.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Wong, Ian; Protopapa, Silvia; Pinilla-Alonso, Noemi; Stansberry, John A.; Holler, Bryan J.; Cook, Jason C.; Souza-Feliciano, Ana Carolina (April 2024). "Moderate D/H ratios in methane ice on Eris and Makemake as evidence of hydrothermal or metamorphic processes in their interiors: Geochemical analysis". Icarus. 412. arXiv:2309.05549. Bibcode:2024Icar..41215999G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2024.115999. S2CID 261696907. Retrieved 12 March 2024.