| This article has an unclear citation style. The references used may be made clearer with a different or consistent style of citation and footnoting. (February 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Huang Yanpei | |

|---|---|

| 黃炎培 | |

| |

| Chairman of the China Democratic Political League | |

| In office 19 March 1941 – 10 October 1941 | |

| Succeeded by | Zhang Lan |

| Chairman of the China National Democratic Construction Association | |

| In office 16 December 1945 – 21 December 1965 | |

| Succeeded by | Hu Juewen |

| Minister of Light Industry | |

| In office 1 October 1949 – September 1954 | |

| Premier | Zhou Enlai |

| Succeeded by | Jia Tuofu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 October 1878 Neishidi, Chuansha, Jiangsu |

| Died | 21 December 1965(1965-12-21) (aged 87) |

| Political party | China Democratic League China National Democratic Construction Association |

| Alma mater | Nanyang Public School |

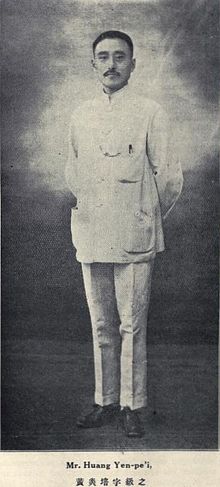

Huang Yanpei (Chinese: 黃炎培; pinyin: Huáng Yánpéi; Wade–Giles: Huang Yen-pe'i; 1 October 1878 – 21 December 1965) was a Chinese educator, writer, and politician. He was a founding pioneer of the China Democratic League and the China National Democratic Construction Association, which are among the eight legally recognised minor political parties in China under the Chinese Communist Party's united front.

Names

Huang was also known by his courtesy name Renzhi (任之; Rènzhī) and art name Chunan (楚南; Chǔnán).

Early life

Huang was born in Neishidi, Chuansha, Jiangsu (now part of Pudong, Shanghai) during the reign of the Guangxu Emperor of the Qing dynasty. His mother died when he was 13 and his father died when he was 17, so he lived with his maternal grandfather, who gave him a traditional Chinese education. In his young age, he studied at Dongye School (東野學堂) and read the Four Books and Five Classics. Before he reached adulthood, he worked as an informal teacher in his hometown to support his family.

In 1899, Huang topped the imperial examination in Songjiang Prefecture, which covered much of present-day Shanghai, and obtained the position of a xiucai. He later received financial support from his uncle to read Western studies.

In 1901, Huang enrolled in Nanyang Public School (now Shanghai Jiao Tong University) and met Cai Yuanpei, who was then teaching the Chinese language there. One year later, Huang obtained the position of a juren in the imperial examination in Jiangnan. Some time later, he left school in protest against the expulsion of his fellow students, who had been expelled for allegedly showing disrespect towards a teacher by leaving an empty ink bottle on the teacher's desk – an act interpreted as suggesting that the teacher was unlearned because ink metaphorically referred to knowledge.

Huang then returned to Chuansha, where he set up a Chuansha Primary School (川沙小學) for children. During this time, he read Yan Fu's Tian Yan Lun — a translation of Thomas Henry Huxley's Evolution and Ethics — and other books on Western ideas.

In 1903, while giving a talk in Nanhui District, Huang was accused of being an anti-government revolutionary, and was arrested and imprisoned. He was released on bail with the help of William Burke, an American missionary, and narrowly escaped death as he left the prison just one hour before an order for his execution from the Jiangsu provincial government reached the local government in Nanhai District. Huang fled to Japan and stayed there for three months before returning to Shanghai, where he continued to set up and run schools.

In 1905, Huang was introduced by Cai Yuanpei to join the Tongmenghui. At the same time, he established, ran and taught in various schools, including the Pudong Middle School (浦東中學), and also helped to set up the Organisation for Education Affairs in Jiangsu (江蘇學務總會).

Life in the Republic of China

After the Xinhai Revolution overthrew the Qing dynasty in 1911, Huang became the Head of Civilian Affairs and Head of Education in the Office of the Governor of Jiangsu. He later became the Secretary of Education and reformed education in Jiangsu, planning and setting up several schools. At the same time, he was also the vice president of the education society and a travelling reporter for the newspaper Shen Bao.

In 1908, Huang, Tong Shiheng and others founded Pudong Electric Co., Ltd. (浦東電氣股份有限公司) to provide electricity in Pudong. In 1913, he published an article, "Discussion on schools adopting a practical stance towards education", to express his thoughts on how education should be tailored towards pragmatism. Between February 1914 and early 1917, Huang, working as a reporter for Shen Bao, visited and observed various schools throughout China. In April 1915, he followed an industrial organisation to the United States, where he visited 52 schools in 25 cities and saw that vocational education was very popular there. He visited Japan, the Philippines and Southeast Asia to observe education in those countries. He made notes from his observations, compiled them and had them published.

In 1917, Huang travelled to Britain to observe the British education system. On May 6, 1917, with support from various businesses and the education sector, Huang founded the National Association of Vocational Education of China (中華職業教育社) in Shanghai. A year later, he established the Chinese Vocational School (中華職業學校). Over the next ten years, Huang remained active in the education sector, using the Chinese Vocational School to expand his activities. During the May Fourth Movement of 1919, he used his position as the Secretary of Education to rally support from the schools in Shanghai to disrupt classes and stage demonstrations.

In 1921, Huang was appointed Education Minister by the Beiyang government but he refused to accept the appointment. In 1922, he drafted the educational system and set up more schools. Five years later, he ran a Life Magazine (生活周刊) to further publish his thoughts and ideas.

In 1927, when the Kuomintang was in conflict with the Chinese Communist Party, Huang was accused of being a "scholar-tyrant" (學閥) – a term to describe those who attempted to expand their political influence through education – and had an order issued for his arrest. He escaped to Dalian and returned to Shanghai only after Chiang Kai-shek withdrew the order for his arrest.

Life during World War II

After the Mukden Incident in 1931, Huang became worried about Japanese aggression towards China so he took part in anti-Japanese activities. He also set up a newsletter, "Newsletter on Saving the Nation" (救國通訊), to publish his ideas and stir up patriotic sentiments among the Chinese. A year later, he sent a message throughout China, urging everyone to put aside their differences and unite to resist the Japanese.

After the January 28 Incident in 1932, Huang and other influential men in Shanghai formed the Shanghai Citizen Preservation Organisation (上海市民維持會) to raise funds to support the 19th Route Army and preserve Shanghai's economy and security. Their activities lasted until Shanghai fell to the Japanese in 1937.

Following the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Huang moved to Chongqing, the wartime capital of the Republic of China government, and served as a representative in the National Defence Council. A year later, he became a member of the People's Political Council. In 1941, he founded the China Democratic League with Zhang Lan and others and served as its first chairman. In 1945, he established the China Democratic National Construction Association with Hu Juewen and others and served as its first chairperson.

Life during the Chinese Civil War

In July 1945, in an attempt to mediate the conflict between the Kuomintang and Chinese Communist Party, Huang, Zhang Bojun and others travelled from Chongqing to Yan'an to meet Communist leader Mao Zedong.

After returning to Chongqing, Huang wrote a book, Return from Yan'an, describing a conversation he had with Mao — widely known as the "Zhou Qi Lü" (周期率; 'cycle rate') conversation. Huang had said,

I have lived for more than 60 years. Let us not talk about what I have heard. Whatever I saw with my own eyes, it fits the saying: "The rise of something may be fast, but its downfall is equally swift." Has any person, family, community, place, or even a nation, ever managed to break out of this cycle? Usually, in the initial stage, everyone is fully focused and puts in their best efforts. Maybe conditions were bad at the time, and everyone has to struggle to survive. Once the times change for the better, everyone loses focus and becomes lazy. In certain cases, as it has been a long time, complacency breeds, spreads and becomes a social norm. When this happens, even if the people are very capable, they can neither reverse the situation nor salvage it. There are also cases where a nation progresses and prospers — its rise could be either natural or due to rapid industrialisation spurred by a desire for progress. When all human resources have been exhausted and problems arise in management, the environment becomes more complicated and they lose control of the situation. Throughout history, there have been many examples: a ruler neglects state affairs and eunuchs use the opportunity to seize power; a good system of governance ceases to function after the person who initiated it dies; people who lust for glory but end up in humiliation. None has managed to break out of this cycle.

Mao had replied,

The people from the government; the government is the nation's body. A new path lies ahead and it belongs to the people. The people build their own nation; everyone has a role to play. The government should pay attention to the people and the political party should perform its duty to its utmost and govern with virtue. We will not follow in the footsteps of those before us who have failed. The problem of a good system of governance ceasing to function after its initiator's death can be avoided. We have already discovered a new path. We can break out of this cycle. This new path belongs to the people. The government will not become complacent only if it is under the supervision of the people. If everyone takes responsibility, a good system of governance will prevail.

During the Chinese Civil War, Huang resigned from the People's Political Council in protest against the war and returned to Shanghai, where he continued to set up and run schools.

Life in the People's Republic of China

After the Chinese Communist Party established the People's Republic of China in 1949, Huang served a member of the Central People's Government, Vice Premier of the State Council, and Minister of Light Industry. He also consecutively served as the Vice Chairman in the second, third and fourth Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference.

Despite holding positions in the Communist government, Huang disagreed with some of its policies and was particularly opposed to state monopoly in purchasing and marketing. Mao Zedong even once called Huang "a spokesperson for capitalists". Nevertheless, Huang managed to retain his positions in the National People's Congress and Political Consultative Conference when the Chinese Communist Party started purging non-communist members from government bodies.

Death

Huang died on December 21, 1965, in Beijing and was cremated and interred in the Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery.

Family

- Spouses

- Wang Jiusi (王糾思; died 1940), Huang's first wife.

- Yao Weijun (姚維鈞; 1909–1968), Huang's second wife who married him in 1942. She was a university graduate and she helped Huang in writing the book Return from Yan'an. She committed suicide on January 20, 1968, by overdosing on sleeping pills.

- Children

- Huang Fanggang (黃方剛; 1901–1944), graduated from Carleton University and obtained a PhD in philosophy from Harvard University.

- Huang Jingwu (黃競武; 1903–1949), graduated from Tsinghua University and obtained a master's degree in economics from Harvard University.

- Huang Lu (黃路;1907-2001), a teacher.

- Huang Wanli (1911–2001), a hydraulics professor.

- Huang Xiaotong (黃小同; 1913-1996), a teacher.

- Huang Daneng (黃大能; 1916–2010), served as the Vice Director of the Chinese Society for Vocational Education. He was also a technical specialist in concrete.

- Huang Xuechao (黃學潮; 1920-)

- Huang Suhui (黃素回; 1923-)

- Huang Bixin (黃必信; 1925-1966), a college lecturer. He and his wife committed suicide during the Cultural Revolution.

- Huang Dangshi (黃當時; 1943-)

- Huang Dingnian (黃丁年; 1944-), an engineer.

- Huang Fangyi (黃方毅; 1946-), obtained a master's degree from Duke University. He worked in the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and participated in research on economics at Beijing University. He is also a visiting professor at the Johns Hopkins University and Columbia University and is involved in Chinese politics.

- Huang Gang (黃剛; 1949-)

- Grandchildren

- Richard Shih-chao Huang (黃施超; 1932–2004), Huang Fanggang's son. He was a rocket scientist in the United States.

- Huang Mengfu, Huang Jingwu's son. He is the Vice Chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference.

- Huang Qieyuan (黃且圓; 1939-2012), a mathematician.

- Huang Guanhong (黃觀鴻), Huang Wanli's son. He is a professor in Tianjin University.

- Other relatives

- Huang Tzu (1904–1938), a musician. He was the son of Huang Hongpei (黃洪培), Huang Yanpei's cousin.

- Huang Peiying (黃培英), a wool knitting specialist in China in the 1930s. She was the daughter of Huang Shihuan (黃士煥), a distant uncle of Huang Yanpei.

Appearances in media

In 2010, CCTV-8 produced a 25-episode television series based on Huang Yanpei's life. It was titled Huang Yanpei and starred Zhang Tielin as the eponymous character.

Notes

- (我生六十多年,耳聞姑且不論,凡親眼所見,真所謂『其興也浡焉,其亡也忽焉』,一人,一家,一團體,一地方,乃至一國,不少單位都沒有能跳出這周期率的支配力。大凡初時聚精會神,無一事不用心,無一人不儘力,也許那時艱難困苦,只有從萬死中覓取一生。既而環境漸漸好轉了,精神也就漸漸放下了。有的因為歷時長久,自然地惰性發作,由少數演為多數,到風氣養成,雖有大力,無法扭轉,並且無法補救。也有為了區域一步步擴大了,它的擴大,有的出於自然發展,有的為功業欲所驅使,強求發展,到幹部人才漸見竭蹶、艱於應付的時候,環境倒越加複雜起來了,控制力不免趨於薄弱了。一部歷史,『政怠宦成』的也有,『人亡政息』的也有,『求榮取辱』的也有。總之沒有能跳出這周期率。)

- ((民為政本,國為政體,新路在幄,是為民主。民主立國,人人盡責,唯政當察於百姓,為黨方得盡心敬事,秉政施德,固不會蹈前車之覆,亦可免人亡政息之禍焉。)我們已經找到了新路,我們能跳出這周期率。這條新路,就是民主。只有讓人民起來監督政府,政府才不敢鬆懈。只有人人起來負責,才不會人亡政息。)

External links

- Huang Yanpei on shanghaiguide.org

- Huang Yuan-pei (Huang Yanpei) 黃炎培 Archived 2015-04-09 at the Wayback Machine from Biographies of Prominent Chinese c.1925.

- Vice premiers of the People's Republic of China

- 1878 births

- 1965 deaths

- Chairpersons of the China Democratic League

- Chinese non-fiction writers

- Educators from Shanghai

- Members of the China National Democratic Construction Association

- People's Republic of China politicians from Shanghai

- Republic of China politicians from Shanghai

- 20th-century Chinese writers

- National Chiao Tung University (Shanghai) alumni

- Vice Chairpersons of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference

- Vice Chairpersons of the National People's Congress

- Writers from Shanghai