| Revision as of 15:03, 3 November 2024 edit94.255.152.53 (talk) →Mental disorders: gallery← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:08, 3 November 2024 edit undo94.255.152.53 (talk) →Toxicity: removed rat study ("Amelioration of ethanol-induced neurotoxicity in the neonatal rat central nervous system by antioxidant therapy")Tag: references removedNext edit → | ||

| Line 812: | Line 812: | ||

| The WHO classifies alcohol as a toxic substance.<ref name="WHO" /> More specifically, ethanol is categorized as a | The WHO classifies alcohol as a toxic substance.<ref name="WHO" /> More specifically, ethanol is categorized as a | ||

| ],<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Guillén-Mancina |first1=E |last2=Calderón-Montaño |first2=JM |last3=López-Lázaro |first3=M |title=Avoiding the ingestion of cytotoxic concentrations of ethanol may reduce the risk of cancer associated with alcohol consumption. |journal=Drug and alcohol dependence |date=1 February 2018 |volume=183 |pages=201-204 |doi=10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.11.013 |pmid=29289868}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lieber CS | title = Mechanism of ethanol induced hepatic injury | journal = Pharmacology & Therapeutics | volume = 46 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–41 | date = 1990 | pmid = 2181486 | doi = 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90032-w }}</ref> ], |

],<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Guillén-Mancina |first1=E |last2=Calderón-Montaño |first2=JM |last3=López-Lázaro |first3=M |title=Avoiding the ingestion of cytotoxic concentrations of ethanol may reduce the risk of cancer associated with alcohol consumption. |journal=Drug and alcohol dependence |date=1 February 2018 |volume=183 |pages=201-204 |doi=10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.11.013 |pmid=29289868}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lieber CS | title = Mechanism of ethanol induced hepatic injury | journal = Pharmacology & Therapeutics | volume = 46 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–41 | date = 1990 | pmid = 2181486 | doi = 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90032-w }}</ref> ],<ref name="pmid20617045">{{cite journal |vauthors=Brust JC |title=Ethanol and cognition: indirect effects, neurotoxicity and neuroprotection: a review |journal=International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health |volume=7 |issue=4 |pages=1540–57 |date=April 2010 |pmid=20617045 |pmc=2872345 |doi=10.3390/ijerph7041540 |doi-access=free}}</ref> and ],<ref name="pmid17505609">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bellé M, ((Sartori Sd)), Rossi AG | title = Alcoholism: effects on the cochleo-vestibular apparatus | journal = Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology | volume = 73 | issue = 1 | pages = 110–116 | date = January 2007 | pmid = 17505609 | pmc = 9443585 | doi = 10.1016/s1808-8694(15)31132-0 }}</ref> which has acute toxic effects on the cells, liver, the nervous system, and the ears, respectively. However, ethanol's acute effects on these organs are usually reversible. This means that even with a single episode of heavy drinking, the body can typically repair itself from the initial damage. Methanol laced alcohol on the other hand can cause blindness even in small quantities. | ||

| Ethanol is nutritious but highly intoxicating for most animals, which typically tolerate only up to 4% in their diet. However, a 2024 study found that ]s fed sugary solutions containing 1% to 80% ethanol for a week showed no adverse effects on behavior or lifespan.<ref>{{cite news |title=Hornets can hold their alcohol like no other animal on Earth |url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/2452557-hornets-can-hold-their-alcohol-like-no-other-animal-on-earth/ |work=New Scientist}}</ref> | Ethanol is nutritious but highly intoxicating for most animals, which typically tolerate only up to 4% in their diet. However, a 2024 study found that ]s fed sugary solutions containing 1% to 80% ethanol for a week showed no adverse effects on behavior or lifespan.<ref>{{cite news |title=Hornets can hold their alcohol like no other animal on Earth |url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/2452557-hornets-can-hold-their-alcohol-like-no-other-animal-on-earth/ |work=New Scientist}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 17:08, 3 November 2024

| It has been suggested that this article be split into a new article titled Alcohol and society. (discuss) (October 2024) |

Pharmaceutical compound

| |||

| |||

| Clinical data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈɛθənɒl/ | ||

| Other names | Absolute alcohol; Alcohol (USPTooltip United States Pharmacopeia); Cologne spirit; Drinking alcohol; Ethanol (JANTooltip Japanese Accepted Name); Ethylic alcohol; EtOH; Ethyl alcohol; Ethyl hydrate; Ethyl hydroxide; Ethylol; Grain alcohol; Hydroxyethane; Methylcarbinol | ||

| Pregnancy category |

| ||

| Dependence liability | Physical: Very High Psychological: Moderate | ||

| Addiction liability | Moderate (10–15%) | ||

| Routes of administration | Common: By mouth Uncommon: Suppository, inhalation, ophthalmic, insufflation, injection | ||

| Drug class | Depressant; Anxiolytic; Analgesic; Euphoriant; Sedative; Emetic; Diuretic; General anesthetic | ||

| ATC code | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Legal status |

| ||

| Pharmacokinetic data | |||

| Bioavailability | 80%+ | ||

| Protein binding | Weakly or not at all | ||

| Metabolism | Liver (90%): • Alcohol dehydrogenase • MEOS (CYP2E1) | ||

| Metabolites | Acetaldehyde; Acetic acid; Acetyl-CoA; Carbon dioxide; Ethyl glucuronide; Ethyl sulfate; Water | ||

| Onset of action | Peak concentrations: • Range: 30–90 minutes • Mean: 45–60 minutes • Fasting: 30 minutes | ||

| Elimination half-life | Constant-rate elimination at typical concentrations: • Range: 10–34 mg/dL/hour • Mean (men): 15 mg/dL/hour • Mean (women): 18 mg/dL/hr At very high concentrations (t1/2): 4.0–4.5 hours | ||

| Duration of action | 6–16 hours (amount of time that levels are detectable) | ||

| Excretion | • Major: metabolism (into carbon dioxide and water) • Minor: urine, breath, sweat (5–10%) | ||

| Identifiers | |||

IUPAC name

| |||

| CAS Number | |||

| PubChem CID | |||

| IUPHAR/BPS | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| UNII | |||

| KEGG | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| PDB ligand | |||

| Chemical and physical data | |||

| Formula | C2H6O | ||

| Molar mass | 46.069 g·mol | ||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| Density | 0.7893 g/cm (at 20 °C) | ||

| Melting point | −114.14 ± 0.03 °C (−173.45 ± 0.05 °F) | ||

| Boiling point | 78.24 ± 0.09 °C (172.83 ± 0.16 °F) | ||

| Solubility in water | Miscible mg/mL (20 °C) | ||

SMILES

| |||

InChI

| |||

Alcohol (from Arabic الكحل (al-kuḥl) 'kohl'), sometimes referred to by the chemical name ethanol, is the second most consumed psychoactive drug globally behind caffeine, and one of the most widely abused drugs in the world. It is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant, decreasing electrical activity of neurons in the brain. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies alcohol as a toxic, psychoactive, dependence-producing, and carcinogenic substance.

Alcohol is found in fermented beverages such as beer, wine, and distilled spirit – in particular, rectified spirit, and serves various purposes; it is used as a recreational drug, for example by college students, for self-medication, and in warfare. It is also frequently involved in alcohol-related crimes such as drunk driving, public intoxication, and underage drinking. Some religions, including Catholicism, incorporate the use of alcohol for spiritual purposes.

Short-term effects from moderate consumption include relaxation, decreased social inhibition, and euphoria, while binge drinking may result in cognitive impairment, blackout, and hangover. Excessive alcohol intake causes alcohol poisoning, characterized by unconsciousness or, in severe cases, death. Long-term effects are considered to be a major global public health issue and includes alcoholism, abuse, alcohol withdrawal, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), liver disease, hepatitis, cardiovascular disease (e.g., cardiomyopathy), polyneuropathy, alcoholic hallucinosis, long-term impact on the brain (e.g., brain damage, dementia), and cancers. According to a 2024 WHO report, these harmful consequences of alcohol use result in 2.6 million deaths annually, accounting for 4.7% of all global deaths.

For roughly two decades, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified alcohol as a Group 1 Carcinogen. In 2023, the WHO declared that there is "no safe amount" of alcohol consumption without health risks. This reflects a global shift in public health messaging, aligning with the long-standing views of the temperance movement, which advocates against the consumption of alcoholic beverages. This shift aligns with the global scientific consensus against alcohol for pregnant women due to the known risks of miscarriage, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs), and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), as well as for individuals under the legal drinking age.

Uses

For non-psychoactive use of alcohol, such as rum-running, see Alcoholic beverage § Uses.Medical

Main article: Alcohols (medicine)Spiritus fortis is a medical term for ethanol solutions with 95% ABV.

When taken by mouth or injected into a vein ethanol is used to treat methanol or ethylene glycol toxicity when fomepizole is not available.

Ethanol, when used to treat or prevent methanol and/or ethylene glycol toxicity, competes with other alcohols for the alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme, lessening metabolism into toxic aldehyde and carboxylic acid derivatives, and reducing the more serious toxic effects of the glycols when crystallized in the kidneys.

Recreational

Further information: § Drinking culture Main article: Drinking cultureDrinking culture is the set of traditions and social behaviors that surround the consumption of alcoholic beverages as a recreational drug and social lubricant. Although alcoholic beverages and social attitudes toward drinking vary around the world, nearly every civilization has independently discovered the processes of brewing beer, fermenting wine and distilling spirits.

Common drinking styles include moderate drinking, social drinking, and binge drinking.

Drinking styles

Source: SAMHSA

In today's society, there is a growing awareness of this, reflected in the variety of approaches to alcohol use, each emphasizing responsible choices. Sober curious describes a mindset or approach where someone is consciously choosing to reduce or eliminate alcohol consumption, not drinking and driving, being aware of your surroundings, not pressuring others to drink, and being able to quit anytime. However, they are not necessarily committed to complete sobriety.

Binge drinking

Binge drinking, or heavy episodic drinking, is drinking alcoholic beverages with an intention of becoming intoxicated by heavy consumption of alcohol over a short period of time, but definitions vary considerably. Binge drinking is a style of drinking that is popular in several countries worldwide, and overlaps somewhat with social drinking since it is often done in groups.

Drinking games involve consuming alcohol as part of the gameplay. They can be risky because they can encourage people to drink more than they intended to. Recent studies link binge drinking habits to a decline in quality of life and a shortened lifespan by 3–6 years.

Definition

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking as a pattern of alcohol consumption that brings a person's blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.08 percent or above. This typically occurs when men consume five or more US standard drinks, or women consume four or more drinks, within about two hours. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines binge drinking slightly differently, focusing on the number of drinks consumed on a single occasion. According to SAMHSA, binge drinking is consuming five or more drinks for men, or four or more drinks for women, on the same occasion on at least one day in the past month.

Light, moderate, responsible, and social drinking

Light drinking, moderate drinking, responsible drinking, and social drinking are often used interchangeably, but with slightly different connotations:

- Light drinking - "At least 12 drinks in the past year but 3 drinks or fewer per week, on average over the past year.", according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- Light alcohol consumption showed no connection to most cancers, but a slight rise in the likelihood of melanoma, breast cancer in females, and prostate cancer in males was observed.

- Moderate drinking - strictly focuses on the amount of alcohol consumed, following alcohol consumption recommendations. This is called "drinking in moderation". The CDC defines "Current moderate drinker – More than 3 drinks but no more than 7 drinks per week for women and more than 3 drinks but no more than 14 drinks per week for men, on average over the past year.".

- According to the WHO nearly half of all alcohol-attributable cancers in the WHO European Region are linked to alcohol consumption, even from "light" or "moderate" drinking – "less than 1.5 litres of wine or less than 3.5 litres of beer or less than 450 millilitres of spirits per week". However, moderate drinking is associated with a further slight increase in cancer risk. Also, moderate drinking may disrupt normal brain functioning.

- Responsible drinking - as defined by alcohol industry standards, often emphasizes personal choice and risk management, unlike terms like "social drinking" or "moderate drinking".

- Critics argue that the alcohol industry's definition does not always align with official recommendations for safe drinking limits.

- Social drinking - refers to casual drinking of alcoholic beverages in a social setting (for example bars, nightclubs, or parties) without an intent to become intoxicated. A social drinker is also defined as a person who only drinks alcohol during social events, such as parties, and does not drink while alone (e.g., at home).

- While social drinking often involves moderation, it does not strictly emphasize safety or specific quantities, unlike moderate drinking. Social settings can involve peer pressure to drink more than intended, which can be a risk factor for excessive alcohol consumption. Regularly socializing over drinks can lead to a higher tolerance for alcohol and potentially dependence, especially in groups where drinking is a central activity. Social drinking does not preclude the development of alcohol dependence. High-functioning alcoholism describes individuals who appear to function normally in daily life despite struggling with alcohol dependence.

Heavy drinking

See also: Alcohol in association football and Football hooliganismA 2007 study at the University of Texas at Austin monitored the drinking habits of 541 students over two football seasons. It revealed that high-profile game days ranked among the heaviest drinking occasions, similar to New Year's Eve. Male students increased their consumption for all games, while socially active female students drank heavily during away games. Lighter drinkers also showed a higher likelihood of risky behaviors during away games as their intoxication increased. This research highlights specific drinking patterns linked to collegiate sports events.

According to a 2022 study, recreational heavy drinking and intoxication have become increasingly prevalent among Nigerian youth in Benin City. Traditionally, alcohol use was more accepted for men, while youth drinking was often taboo. Today, many young people engage in heavy drinking for pleasure and excitement. Peer networks encourage this behavior through rituals that promote intoxication and provide care for inebriated friends. The findings suggest a need to reconsider cultural prohibitions on youth drinking and advocate for public health interventions promoting low-risk drinking practices.

Definition

Heavy alcohol use is defined differently by various health organizations. The CDC defines "Current heavier drinker" as consuming more than 7 drinks per week for women and more than 14 drinks per week for men. Additionally, "Heavy drinking day (also referred to as episodic heavy drinking" is characterized as having 4 or more drinks on a single occasion for women and 5 or more for men, in the past year. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) provides gender-specific guidelines for heavy drinking. According to NIAAA, men who consume five or more US standard drinks in a single day or 15 or more drinks within a week are considered heavy drinkers. For women, the threshold is lower, with four or more drinks in a day or eight or more drinks per week classified as heavy drinking. In contrast, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) takes a different approach to defining heavy alcohol use. SAMHSA considers heavy alcohol use to be engaging in binge drinking behaviors on five or more days within a month. This definition focuses more on the frequency of excessive drinking episodes rather than specific drink counts.

Despite this risk, a 2014 report in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that only 10% of either "heavy drinkers" or "binge drinkers" defined according to the above criteria also met the criteria for alcohol dependence, while only 1.3% of non-binge drinkers met the criteria. An inference drawn from this study is that evidence-based policy strategies and clinical preventive services may effectively reduce binge drinking without requiring addiction treatment in most cases.

Self-medication

The therapeutic index for ethanol is 10%.

Alcohol can have analgesic (pain-relieving) effects, which is why some people with chronic pain turn to alcohol to self-medicate and try to alleviate their physical discomfort.

People with social anxiety disorder commonly self-medicate with alcohol to overcome their highly set inhibitions. However, self-medicating excessively for prolonged periods of time with alcohol often makes the symptoms of anxiety or depression worse. This is believed to occur as a result of the changes in brain chemistry from long-term use. A 2023 systematic review highlights the non-addictive use of alcohol for managing developmental issues, personality traits, and psychiatric symptoms, emphasizing the need for informed, harm-controlled approaches to alcohol consumption within a personalized health policy framework.

A 2023 study suggests that people who drink for both recreational enjoyment and therapeutic reasons, like relieving pain and anxiety/depression/stress, have a higher demand for alcohol compared to those who drink solely for recreation or self-medication. This finding raises concerns, as this group may be more likely to develop alcohol use disorder and experience negative consequences related to their drinking. A significant proportion of patients attending mental health services for conditions including anxiety disorders such as panic disorder or social phobia have developed these conditions as a result of recreational alcohol or sedative use.

Self-medication or mental disorders may make people not decline their drinking despite negative consequences. This can create a cycle of dependence that is difficult to break without addressing the underlying mental health issue.

Unscientific

The American Heart Association warn that "We've all seen the headlines about studies associating light or moderate drinking with health benefits and reduced mortality. Some researchers have suggested there are health benefits from wine, especially red wine, and that a glass a day can be good for the heart. But there's more to the story. No research has proved a cause-and-effect link between drinking alcohol and better heart health."

In folk medicine, consuming a nightcap is for the purpose of inducing sleep. However, alcohol is not recommended by many doctors as a sleep aid because it interferes with sleep quality.

"Hair of the dog", short for "hair of the dog that bit you", is a colloquial expression in the English language predominantly used to refer to alcohol that is consumed as a hangover remedy (with the aim of lessening the effects of a hangover). Many other languages have their own phrase to describe the same concept. The idea may have some basis in science in the difference between ethanol and methanol metabolism. Instead of alcohol, rehydration before going to bed or during hangover may relieve dehydration-associated symptoms such as thirst, dizziness, dry mouth, and headache.

Drinking alcohol may cause subclinical immunosuppression.

Dutch courage

Dutch courage, also known as pot-valiance or liquid courage, refers to courage gained from intoxication with alcohol.

Alcohol use among college students is often used as "liquid courage" in the hookup culture, for them to make a sexual advance in the first place. However, a recent trend called "dry dating" is gaining popularity to replace "liquid courage", which involves going on dates without consuming alcohol.

Consuming alcohol prior to visiting female sex workers is a common practice among some men. Sex workers often resort to using drugs and alcohol to cope with stress.

Alcohol when consumed in high doses is considered to be an anaphrodisiac.

Criminal

See also: Alcohol-related crime For the use of non-intentional offenses, such as drunk walking, see § Alcohol-related crimes.Albeit not a valid intoxication defense, weakening the inhibitions by drunkenness is occasionally used as a tool to commit planned offenses such as property crimes including theft and robbery, and violent crimes including assault, murder, or rape – which sometimes but not always occurs in alcohol-facilitated sexual assaults where the victim is also drugged.

Warfare

Main article: Use of drugs in warfare § Alcohol

Alcohol has a long association of military use, and has been called "liquid courage" for its role in preparing troops for battle, anaesthetize injured soldiers, and celebrate military victories. It has also served as a coping mechanism for combat stress reactions and a means of decompression from combat to everyday life. However, this reliance on alcohol can have negative consequences for physical and mental health. Military and veteran populations face significant challenges in addressing the co-occurrence of PTSD and alcohol use disorder. Military personnel who show symptoms of PTSD, major depressive disorder, alcohol use disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder show higher levels of suicidal ideation.

Alcohol consumption in the US Military is higher than any other profession, according to CDC data from 2013–2017. The Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behaviors among Active Duty Military Personnel published that 47% of active duty members engage in binge drinking, with another 20% engaging in heavy drinking in the past 30 days.

Reports from the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and since suggested that Russian soldiers are drinking significant amount of alcohol (as well as consuming harder drugs), which increases their losses. Some reports suggest that on occasion, alcohol and drugs have been provided to the lower quality troops by their commanders, in order to facilitate their use as expendable cannon fodder.

Food energy

The use of alcohol as a staple food source is considered inconvenient due to the fact that it increases the blood alcohol content (BAC). However, alcohol is a significant source of food energy for individuals with alcoholism and those who engage in binge drinking; For example, individuals with drunkorexia, engage in the combination of self-imposed malnutrition and binge drinking to avoid weight gain from alcohol, to save money for purchasing alcohol, and to facilitate alcohol intoxication. Also, in alcoholics who get most of their daily calories from alcohol, a deficiency of thiamine can produce Korsakoff's syndrome, which is associated with serious brain damage.

The USDA uses a figure of 6.93 kilocalories (29.0 kJ) per gram of alcohol (5.47 kcal or 22.9 kJ per ml) for calculating food energy. For distilled spirits, a standard serving in the United States is 44 ml (1.5 US fl oz), which at 40% ethanol (80 proof), would be 14 grams and 98 calories.

Alcoholic drinks are considered empty calorie foods because other than food energy they contribute no essential nutrients. Alcohol increases insulin response to glucose promoting fat storage and hindering carb/fat burning oxidation. This excess processing in the liver acetyl CoA can lead to fatty liver disease and eventually alcoholic liver disease.

Spiritual

See also: Alcohol and religion

Spiritual use of moderate alcohol consumption is found in some religions and schools with esoteric influences, including the Hindu tantra sect Aghori, in the Sufi Bektashi Order and Alevi Jem ceremonies, in the Rarámuri religion, in the Japanese religion Shinto, by the new religious movement Thelema, in Vajrayana Buddhism, and in Vodou faith of Haiti.

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2024) |

Contraindication

Pregnancy

In the US, alcohol is subject to the FDA drug labeling Pregnancy Category X (Contraindicated in pregnancy).

Minnesota, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Wisconsin have laws that allow the state to involuntarily commit pregnant women to treatment if they abuse alcohol during pregnancy.

Risks

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

Main article: Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

Ethanol is classified as a teratogen—a substance known to cause birth defects; according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), alcohol consumption by women who are not using birth control increases the risk of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs). This group of conditions encompasses fetal alcohol syndrome, partial fetal alcohol syndrome, alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder, static encephalopathy, and alcohol-related birth defects. The CDC currently recommends complete abstinence from alcoholic beverages for women of child-bearing age who are pregnant, trying to become pregnant, or are sexually active and not using birth control.

In South Africa, some populations have rates as high as 9%.

Miscarriage

Miscarriage, also known in medical terms as a spontaneous abortion, is the death and expulsion of an embryo or fetus before it can survive independently.

Alcohol consumption is a risk factor for miscarriage.

Sudden infant death syndrome

Main article: Sudden infant death syndromeDrinking of alcohol by parents is linked to sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). One study found a positive correlation between the two during New Years celebrations and weekends. Another found that alcohol use disorder was linked to a more than doubling of risk.

Adverse effects

Main articles: Alcohol and health and Alcoholism § Moderate drinking See also: Health effects of wine

Alcohol has a variety of short-term and long-term adverse effects. Alcohol has both short-term, and long-term effects on the memory, and sleep. It also has reinforcement-related adverse effects, including alcoholism, dependence, and withdrawal; The most severe withdrawal symptoms, associated with physical dependence, can include seizures and delirium tremens, which in rare cases can be fatal. Alcohol use is directly related to considerable morbidity and mortality, for instance due to intoxication and alcohol-related health problems. The World Health Organization advises that there is no safe level of alcohol consumption.

A study in 2015 found that alcohol and tobacco use combined resulted in a significant health burden, costing over a quarter of a billion disability-adjusted life years. Illicit drug use caused tens of millions more disability-adjusted life years.

Drunkorexia is a colloquialism for anorexia or bulimia combined with an alcohol use disorder.

Alcohol is a common cause of substance-induced psychosis or episodes, which may occur through acute intoxication, chronic alcoholism, withdrawal, exacerbation of existing disorders, or acute idiosyncratic reactions. Research has shown that excessive alcohol use causes an 8-fold increased risk of psychotic disorders in men and a 3-fold increased risk of psychotic disorders in women. While the vast majority of cases are acute and resolve fairly quickly upon treatment and/or abstinence, they can occasionally become chronic and persistent. Alcoholic psychosis is sometimes misdiagnosed as another mental illness such as schizophrenia.

An inability to process or exhibit emotions in a proper manner has been shown to exist in people who consume excessive amounts of alcohol and those who were exposed to alcohol while fetuses (FAexp). Also, a significant portion (40–60%) of alcoholics experience emotional blindness. Impairments in theory of mind, as well as other social-cognitive deficits, are commonly found in people who have alcohol use disorders, due to the neurotoxic effects of alcohol on the brain, particularly the prefrontal cortex.

Short-term effects

Main articles: Short-term effects of alcohol consumption and Subjective response to alcohol

The amount of ethanol in the body is typically quantified by blood alcohol content (BAC); weight of ethanol per unit volume of blood. Small doses of ethanol, in general, are stimulant-like and produce euphoria and relaxation; people experiencing these symptoms tend to become talkative and less inhibited, and may exhibit poor judgement. At higher dosages (BAC > 1 gram/liter), ethanol acts as a central nervous system (CNS) depressant, producing at progressively higher dosages, impaired sensory and motor function, slowed cognition, stupefaction, unconsciousness, and possible death. Ethanol is commonly consumed as a recreational substance, especially while socializing, due to its psychoactive effects.

Central nervous system impairment

Alcohol causes generalized CNS depression, is a positive allosteric GABAA modulator and is associated and related with decreased anxiety, decreased social inhibition, sedation, impairment of cognitive, memory, and sensory function, cognitive, memory, motor, and sensory impairment. It slows and impairs cognition and reaction time and the cognitive skills, impairs judgement, interferes with motor function resulting in motor incoordination, numbness, impairs memory formation, and causes sensory impairment.

Binge drinking can cause generalized impairment of neurocognitive function, dizziness, analgesia, amnesia, ataxia (loss of balance, confusion, sedation, slurred speech), general anaesthesia, decreased libido, nausea, vomiting, blackout, spins, stupor, unconsciousness, and hangover.

At very high concentrations, alcohol can cause anterograde amnesia, markedly decreased heart rate, pulmonary aspiration, positional alcohol nystagmus, respiratory depression, shock, coma and death can result due to profound suppression of CNS function alcohol overdose and can finish in consequent dysautonomia.

Gastrointestinal effects

Alcohol can cause nausea and vomiting in sufficiently high amounts (varying by person).

Alcohol stimulates gastric juice production, even when food is not present, and as a result, its consumption stimulates acidic secretions normally intended to digest protein molecules. Consequently, the excess acidity may harm the inner lining of the stomach. The stomach lining is normally protected by a mucosal layer that prevents the stomach from, essentially, digesting itself.

Ingestion of alcohol can initiate systemic pro-inflammatory changes through two intestinal routes: (1) altering intestinal microbiota composition (dysbiosis), which increases lipopolysaccharide (LPS) release, and (2) degrading intestinal mucosal barrier integrity – thus allowing LPS to enter the circulatory system. The major portion of the blood supply to the liver is provided by the portal vein. Therefore, while the liver is continuously fed nutrients from the intestine, it is also exposed to any bacteria and/or bacterial derivatives that breach the intestinal mucosal barrier. Consequently, LPS levels increase in the portal vein, liver and systemic circulation after alcohol intake. Immune cells in the liver respond to LPS with the production of reactive oxygen species, leukotrienes, chemokines and cytokines. These factors promote tissue inflammation and contribute to organ pathology.

Hangover

A hangover is the experience of various unpleasant physiological and psychological effects usually following the consumption of alcohol, such as wine, beer, and liquor. Hangovers can last for several hours or for more than 24 hours. Typical symptoms of a hangover may include headache, drowsiness, concentration problems, dry mouth, dizziness, fatigue, gastrointestinal distress (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), absence of hunger, light sensitivity, depression, sweating, hyper-excitability, irritability, and anxiety (often referred to as "hangxiety").

Though many possible remedies and folk cures have been suggested, there is no compelling evidence to suggest that any are effective for preventing or treating hangovers. Avoiding alcohol or drinking in moderation are the most effective ways to avoid a hangover. The socioeconomic consequences of hangovers include workplace absenteeism, impaired job performance, reduced productivity and poor academic achievement. A hangover may also impair performance during potentially dangerous daily activities such as driving a car or operating heavy machinery.

Holiday heart syndrome

Holiday heart syndrome, also known as alcohol-induced atrial arrhythmias, is a syndrome defined by an irregular heartbeat and palpitations associated with high levels of ethanol consumption. Holiday heart syndrome was discovered in 1978 when Philip Ettinger discovered the connection between arrhythmia and alcohol consumption. It received its common name as it is associated with the binge drinking common during the holidays. It is unclear how common this syndrome is. 5-10% of cases of atrial fibrillation may be related to this condition, but it could be as high 63%.

Positional alcohol nystagmus

Main article: Positional alcohol nystagmusPositional alcohol nystagmus (PAN) is nystagmus (visible jerkiness in eye movement) produced when the head is placed in a sideways position. PAN occurs when the specific gravity of the membrane space of the semicircular canals in the ear differs from the specific gravity of the fluid in the canals because of the presence of alcohol.

Allergic-like reactions

Ethanol-containing beverages can cause alcohol flush reactions, exacerbations of rhinitis and, more seriously and commonly, bronchoconstriction in patients with a history of asthma, and in some cases, urticarial skin eruptions, and systemic dermatitis. Such reactions can occur within 1–60 minutes of ethanol ingestion, and may be caused by:

- genetic abnormalities in the metabolism of ethanol, which can cause the ethanol metabolite, acetaldehyde, to accumulate in tissues and trigger the release of histamine, or

- true allergy reactions to allergens occurring naturally in, or contaminating, alcoholic beverages (particularly wine and beer), and

- other unknown causes.

Alcohol flush reaction has also been associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer in those who do drink.

Long-term effects

According to The Lancet, 'four industries (tobacco, unhealthy food, fossil fuel, and alcohol) are responsible for at least a third of global deaths per year'. In 2024, the World Health Organization published a report including these figures.

Due to the long term effects of alcohol abuse, binge drinking is considered to be a major public health issue.

The impact of alcohol on aging is multifaceted. The relationship between alcohol consumption and body weight is the subject of inconclusive studies. Alcoholic lung disease is disease of the lungs caused by excessive alcohol. However, the term 'alcoholic lung disease' is not a generally accepted medical diagnosis.

Alcohol's overall effect on health is uncertain. While some studies suggest moderate consumption might have some benefit, others find any amount increases health risks. This uncertainty is due to conflicting research methods and potential biases, including counting former drinkers as abstainers and the possibility of alcohol industry influence. Because of these issues, experts advise against using alcohol for health reasons. For example, in 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that there is currently no conclusive evidence from studies that the potential benefits of moderate alcohol consumption for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes outweigh the increased cancer risk associated with these drinking levels for individual consumers.

Despite being a widespread issue, social stigma around problematic alcohol use or alcoholism discourages over 80% from seeking help.

Alcoholism

Main articles: Alcoholism, Alcoholism in adolescence, and Alcoholism in family systems See also: Quit lit (alcohol cessation)

Alcoholism or its medical diagnosis alcohol use disorder refers to alcohol addiction, alcohol dependence, dipsomania, and/or alcohol abuse. It is a major problem and many health problems as well as death can result from excessive alcohol use. Alcohol dependence is linked to a lifespan that is reduced by about 12 years relative to the average person. In 2004, it was estimated that 4% of deaths worldwide were attributable to alcohol use. Deaths from alcohol are split about evenly between acute causes (e.g., overdose, accidents) and chronic conditions. The leading chronic alcohol-related condition associated with death is alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol dependence is also associated with cognitive impairment and organic brain damage. Some researchers have found that even one alcoholic drink a day increases an individual's risk of health problems by 0.4%.

Stigma surrounding alcohol use disorder is particularly strong and different from the stigma attached to other mental illnesses not caused by substances. People with this condition are seen less as truly ill, face greater blame and social rejection, and experience higher structural discrimination risks.

Two or more consecutive alcohol-free days a week have been recommended to improve health and break dependence.

Dry drunk is an expression coined by the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous that describes an alcoholic who no longer drinks but otherwise maintains the same behavior patterns of an alcoholic.

A high-functioning alcoholic (HFA) is a person who maintains jobs and relationships while exhibiting alcoholism.

Many Native Americans in the United States have been harmed by, or become addicted to, drinking alcohol.

Brain damage

While many people associate alcohol's effects with intoxication, the long-term impact of alcohol on the brain can be severe. Binge drinking, or heavy episodic drinking, can lead to alcohol-related brain damage that occurs after a relatively short period of time. This brain damage increases the risk of alcohol-related dementia, and abnormalities in mood and cognitive abilities.

Alcohol can cause Wernicke encephalopathy and Korsakoff syndrome which frequently occur simultaneously, known as Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome. Lesions, or brain abnormalities, are typically located in the diencephalon which result in anterograde and retrograde amnesia, or memory loss.

Dementia

Main article: Alcohol-related dementiaAlcohol-related dementia (ARD) is a form of dementia caused by long-term, excessive consumption of alcohol, resulting in neurological damage and impaired cognitive function.

Marchiafava–Bignami disease

Main article: Marchiafava–Bignami disease

Marchiafava–Bignami disease is a progressive neurological disease of alcohol use disorder, characterized by corpus callosum demyelination and necrosis and subsequent atrophy. The disease was first described in 1903 by the Italian pathologists Amico Bignami and Ettore Marchiafava in an Italian Chianti drinker.

Symptoms can include, but are not limited to lack of consciousness, aggression, seizures, depression, hemiparesis, ataxia, apraxia, coma, etc. There will also be lesions in the corpus callosum.

Liver damage

Consuming more than 30 grams of pure alcohol per day over an extended period can significantly increase the risk of developing alcoholic liver disease. During the metabolism of alcohol via the respective dehydrogenases, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is converted into reduced NAD. Normally, NAD is used to metabolize fats in the liver, and as such alcohol competes with these fats for the use of NAD. Prolonged exposure to alcohol means that fats accumulate in the liver, leading to the term 'fatty liver'. Continued consumption (such as in alcohol use disorder) then leads to cell death in the hepatocytes as the fat stores reduce the function of the cell to the point of death. These cells are then replaced with scar tissue, leading to the condition called cirrhosis.

Cancer

Alcoholic beverages have been classified as carcinogenic by leading health organizations for more than two decades, including the WHO's IARC (Group 1 carcinogens) and the U.S. NTP, raising concerns about the potential cancer risk associated with alcohol consumption.

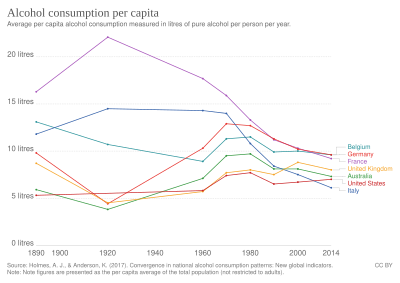

In 2023 the WHO highlighted a statistic: nearly half of all alcohol-attributable cancers in the WHO European Region are linked to alcohol consumption, even from "light" or "moderate" drinking – "less than 1.5 litres of wine or less than 3.5 litres of beer or less than 450 millilitres of spirits per week". This new information suggests that these consumption levels should now be considered high-risk. Many countries exceed these levels by a significant margin. Echoing the WHO's view, a growing number of national public health agencies are prioritizing complete abstinence (teetotalism) and stricter drinking guidelines in their alcohol consumption recommendations.

Drinking alcohol increases the risk for breast cancer. For women in Europe, breast cancer represents the most significant alcohol-related cancer burden. Alcohol is also a major cause for head and neck cancer, especially laryngeal cancer.

This risk is even higher when alcohol is used together with tobacco.

Qualitative analysis reveals that the alcohol industry likely misinforms the public about the alcohol-cancer link, similar to the tobacco industry. The alcohol industry influences alcohol policy and health messages, including those for schoolchildren.

Cardiovascular disease

Main article: Alcohol and cardiovascular diseaseExcessive daily alcohol consumption and binge drinking can cause a higher risk of stroke, coronary artery disease, heart failure, fatal hypertensive disease, and fatal aortic aneurysm.

A 2010 study reviewed research on alcohol and heart disease. They found that moderate drinking did not seem to worsen things for people who already had heart problems. But importantly, the researchers did not say that people who do not drink should start in order to improve their heart health. Thus, the safety and potential positive effect of light drinking on the cardiovascular system has not yet been proven. Still alcohol is a major health risk, and even if moderate drinking lowers the risk of some cardiovascular diseases it might increase the risk of others. Therefore starting to drink alcohol in the hope of any benefit is not recommended.

The World Heart Federation (2022) recommends against any alcohol intake for optimal heart health.

It has also been pointed out that the studies suggesting a positive link between red wine consumption and heart health had flawed methodology in the form of comparing two sets of people which were not actually appropriately paired.

Cardiomyopathy

Main article: Alcoholic cardiomyopathy

Alcoholic cardiomyopathy (ACM) is a disease in which the long-term consumption of alcohol leads to heart failure. ACM is a type of dilated cardiomyopathy. The heart is unable to pump blood efficiently, leading to heart failure. It can affect other parts of the body if the heart failure is severe. It is most common in males between the ages of 35 and 50.

Hearing loss

Alcohol, classified as an ototoxin (ear toxin), can contribute to hearing loss sometimes referred to as "cocktail deafness" after exposure to loud noises in drinking environments.

Children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) are at an increased risk of having hearing difficulties.

Withdrawal syndrome

Discontinuation of alcohol after extended heavy use and associated tolerance development (resulting in dependence) can result in withdrawal. Alcohol withdrawal can cause confusion, paranoia, anxiety, insomnia, agitation, tremors, fever, nausea, vomiting, autonomic dysfunction, seizures, and hallucinations. In severe cases, death can result.

Delirium tremens is a condition that requires people with a long history of heavy drinking to undertake an alcohol detoxification regimen.

Alcohol is one of the more dangerous drugs to withdraw from. Drugs which help to re-stabilize the glutamate system such as N-acetylcysteine have been proposed for the treatment of addiction to cocaine, nicotine, and alcohol.

Cohort studies have demonstrated that the combination of anticonvulsants and benzodiazepines is more effective than other treatments in reducing alcohol withdrawal scores and shortening the duration of intensive care unit stays.

Nitrous oxide has been shown to be an effective and safe treatment for alcohol withdrawal. The gas therapy reduces the use of highly addictive sedative medications (like benzodiazepines and barbiturates).

Cortisol

Main article: Alcohol and cortisolResearch has looked into the effects of alcohol on the amount of cortisol that is produced in the human body. Continuous consumption of alcohol over an extended period of time has been shown to raise cortisol levels in the body. Cortisol is released during periods of high stress, and can result in the temporary shut down of other physical processes, causing physical damage to the body.

Gout

There is a strong association between gout the consumption of alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages, with wine presenting somewhat less of a risk than beer or spirits.

Ketoacidosis

Main article: Alcoholic ketoacidosisAlcoholic ketoacidosis (AKA) is a specific group of symptoms and metabolic state related to alcohol use. Symptoms often include abdominal pain, vomiting, agitation, a fast respiratory rate, and a specific "fruity" smell. Consciousness is generally normal. Complications may include sudden death.

Mental disorders

Alcohol misuse often coincides with mental health conditions. Many individuals struggling with psychiatric disorders also experience problematic drinking behaviors. For example, alcohol may play a role in depression, with up to 10% of male depression cases in some European countries linked to alcohol use.

Psychiatric genetics research continues to explore the complex interplay between alcohol use, genetic factors, and mental health outcomes; A 2024 study found that excessive drinking and alcohol-related DNA methylation may directly contribute to the causes of mental disorders, possibly through the altered expression of affected genes.

Austrian syndrome

Austrian syndrome, also known as Osler's triad, is a medical condition that was named after Robert Austrian in 1957. The presentation of the condition consists of pneumonia, endocarditis, and meningitis, all caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. It is associated with alcoholism due to hyposplenism (reduced splenic functioning) and can be seen in males between the ages of 40 and 60 years old. Robert Austrian was not the first one to describe the condition, but Richard Heschl (around 1860s) or William Osler were not able to link the signs to the bacteria because microbiology was not yet developed.

The leading cause of Osler's triad (Austrian syndrome) is Streptococcus pneumoniae, which is usually associated with heavy alcohol use.

Polyneuropathy

Main article: Alcoholic polyneuropathyAlcoholic polyneuropathy is a neurological disorder in which peripheral nerves throughout the body malfunction simultaneously. It is defined by axonal degeneration in neurons of both the sensory and motor systems and initially occurs at the distal ends of the longest axons in the body. This nerve damage causes an individual to experience pain and motor weakness, first in the feet and hands and then progressing centrally. Alcoholic polyneuropathy is caused primarily by chronic alcoholism; however, vitamin deficiencies are also known to contribute to its development.

Specific population

Pregnant women

Babies exposed to alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and some antidepressants (SSRIs) during pregnancy may experience neonatal withdrawal.

The onset of clinical presentation typically appears within 48 to 72 hours of birth but may take up to 8 days.

Other effects

Alcohol consumption is associated with lower sperm concentration, percentage of normal morphology, and semen volume, but not sperm motility.

Alcohol consumption may increase the risk of sleep disorders, including insomnia, restless legs syndrome, and sleep apnea.

Frequent drinking of alcoholic beverages is a major contributing factor in cases of hypertriglyceridemia.

Excess alcohol use is frequently associated with porphyria cutanea tarda (PTC).

Alcohol consumption is a risk factor for Dupuytren's contracture.

The majority of those with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease experience respiratory reactions to alcohol.

Social issues

Alcohol-related crimes

Main article: Alcohol-related crimeAlcohol use is stereotypically associated with crime, both violent and non-violent. Some crimes are uniquely tied to alcohol, such as public intoxication or underage drinking, while others are simply more likely to occur together with alcohol consumption. Crime perpetrators are much more likely to be intoxicated than crime victims. Many alcohol laws have been passed to criminalize various alcohol-related activities. Underage drinking and drunk driving are the most prevalent alcohol-specific offenses in the United States and a major problem in many countries worldwide. About one-third of arrests in the United States involve alcohol misuse, and arrests for alcohol-related crimes constitute a high proportion of all arrests made by police in the U.S. and elsewhere. In general, programs aimed at reducing society's consumption of alcohol, including education in schools, are seen as an effective long-term solution. Strategies aiming to reduce alcohol consumption among adult offenders have various estimates of effectiveness. Policing alcohol-related street disorder and enforcing compliance checks of alcohol-dispensing businesses has proven successful in reducing public perception of and fear of criminal activities.

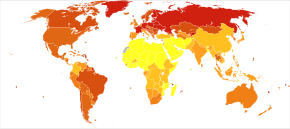

In the early 2000s, the monetary cost of alcohol-related crime in the United States alone has been estimated at over $205 billion, twice the economic cost of all other drug-related crimes. In a similar period in the United Kingdom, the cost of crime and its antisocial effects was estimated at £7.3 billion. Another estimate for the UK for yearly cost of alcohol-related crime suggested double that estimate, at between £8 and 13 billion. Risky patterns of drinking are particularly problematic in and around Russia, Mexico and some parts of Africa. Alcohol is more commonly associated with both violent and non-violent crime than are drugs like marijuana.

Passive drinking, like passive smoking, refers to the damage done to others as a result of drinking alcoholic beverages. These include the unborn fetus and children of parents who drink excessively, drunk drivers, accidents, domestic violence and alcohol-related sexual assaults

Public-order crimes

See also: Passive drinkingPublic-order crimes caused by drinking include drunk driving, domestic violence, and alcohol-related sexual assaults.

Automobile accidents

Main articles: Drunk driving and Driving under influence

A 2002 study found 41% of people fatally injured in traffic accidents were in alcohol-related crashes. Misuse of alcohol is associated with more than 40% of deaths that occur in automobile accidents every year. The risk of a fatal car accident increases exponentially with the level of alcohol in the driver's blood.

Most countries have passed laws prohibiting driving a motor vehicle while impaired by alcohol. In the U.S., these crimes are generally referred to as driving under the influence (DUI), although there are many naming variations among jurisdictions, such as driving while intoxicated (DWI). With alcohol consumption, a drunk driver's level of intoxication is typically determined by a measurement of blood alcohol content or BAC; but this can also be expressed as a breath test measurement, often referred to as a BrAC. A BAC or BrAC measurement in excess of the specific threshold level, such as 0.08% in the U.S., defines the criminal offense with no need to prove impairment. In some jurisdictions, there is an aggravated category of the offense at a higher BAC level, such as 0.12%, 0.15% or 0.25%. In many jurisdictions, police officers can conduct field tests of suspects to look for signs of intoxication.

Negligence

Negligence in alcohol consumption can have a ripple effect on environmentally responsible behavior. Examples:

- Consuming alcoholic beverages, which increases urine production and reduces social inhibitions, can lead to public urination. Public urination is illegal in most areas.

- Improper disposal of alcohol bottles is a common problem. Many are not recycled or left behind in public spaces. Discarded alcoholic beverage containers, especially broken glass shards that are difficult to remove, does not only create an eyesore but may also cause flat tires for cyclists, injure wildlife or kids.

- Alcohol consumption can contribute to nighttime noise pollution, especially through loud music played by intoxicated individuals. This disrupts sleep and relaxation for nearby residents, impacting health and productivity. Municipal noise ordinances often establish quiet hours and penalties for violations.

- People under the influence may forget to extinguish outdoor fireplaces, which may create a fire hazard since unchecked fires can escalate into wildfires.

- Drunk cyclists can only be charged if they ride dangerously, cause a crash, or behave disruptively. However, cycling under the influence increases the risk of severe injury, hospital resource use, and even death, according to a study highlighting the importance of safe cycling practices.

Public drunkenness

Main articles: Public intoxication and Drunk walking

Public drunkenness or intoxication is a common problem in many jurisdictions. Public intoxication laws vary widely by jurisdiction, but include public nuisance laws, open-container laws, and prohibitions on drinking alcohol in public or certain areas. The offenders are often lower class individuals and this crime has a very high recidivism rate, with numerous instances of repeated instances of the arrest, jail, release without treatment cycle. The high number of arrests for public drunkenness often reflects rearrests of the same offenders.

Sexual assaults

Main articles: Alcohol and sex and Beer gogglesRape is any sexual activity that occurs without the freely given consent of one of the parties involved. This includes alcohol-facilitated sexual assault which is considered rape in most if not all jurisdictions, or non-consensual condom removal which is criminalized in some countries (see the map below).

A 2008 study found that rapists typically consumed relatively high amounts of alcohol and infrequently used condoms during assaults, which was linked to a significant increase in STI transmission. This also increase the risk of pregnancy from rape for female victims. Some people turn to drugs or alcohol to cope with emotional trauma after a rape; use of these during pregnancy can harm the fetus.

Alcohol-facilitated sexual assault

One of the most common date rape drugs is alcohol, administered either surreptitiously or consumed voluntarily, rendering the victim unable to make informed decisions or give consent. The perpetrator then facilitates sexual assault or rape, a crime known as alcohol- or drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA). However, sex with an unconscious victim is considered rape in most if not all jurisdictions, and some assailants have committed "rapes of convenience" whereby they have assaulted a victim after he or she had become unconscious from drinking too much. The risk of individuals either experiencing or perpetrating sexual violence and risky sexual behavior increases with alcohol abuse, and by the consumption of caffeinated alcoholic drinks.

Non-consensual condom removal

Non-consensual condom removal, or "stealthing", is the practice of a person removing a condom during sexual intercourse without consent, when their sex partner has only consented to condom-protected sex. Purposefully damaging a condom before or during intercourse may also be referred to as stealthing, regardless of who damaged the condom.

Consuming alcohol can be risky in sexual situations. It can impair judgment and make it difficult for both people to give or receive informed sexual consent. However, a history of sexual aggression and alcohol intoxication are factors associated with an increased risk of men employing non-consensual condom removal and engaging in sexually aggressive behavior with female partners.

Wartime sexual violence

The use of alcohol is a documented factor in wartime sexual violence.

For example, rape during the liberation of Serbia was committed by Soviet Red Army soldiers against women during their advance to Berlin in late 1944 and early 1945 during World War II. Serbian journalist Vuk Perišić said about the rapes: "The rapes were extremely brutal, under the influence of alcohol and usually by a group of soldiers. The Soviet soldiers did not pay attention to the fact that Serbia was their ally, and there is no doubt that the Soviet high command tacitly approved the rape."

While there was not a codified international law specifically prohibiting rape during World War II, customary international law principles already existed that condemned violence against civilians. These principles formed the basis for the development of more explicit laws after the war, including the Nuremberg Principles established in 1950.

Violent crime

Main article: Violent crime

The World Health Organization has noted that out of social problems created by the harmful use of alcohol, "crime and violence related to alcohol consumption" are likely the most significant issue. In the United States, 15% of robberies, 63% of intimate partner violence incidents, 37% of sexual assaults, 45–46% of physical assaults and 40–45% of homicides (murders) involved use of alcohol. A 1983 study for the United States found that 54% of violent crime perpetrators, arrested in that country, had been consuming alcohol before their offenses. In 2002, it was estimated that 1 million violent crimes in the U.S. were related to alcohol use. More than 43% of violent encounters with police involve alcohol. Alcohol is implicated in more than two-thirds of cases of intimate partner violence. Studies also suggest there may be links between alcohol abuse and child abuse. In the United Kingdom, in 2015/2016, 39% of those involved in violent crimes were under alcohol influence. A significant portion, 40%, of homicide victims tested positive for alcohol in the US. International studies are similar, with an estimate that 63% of violent crimes worldwide involves the use of alcohol.

The relation between alcohol and violence is not yet fully understood, as its impact on different individuals varies. Studies and theories of alcohol abuse suggest, among others, that use of alcohol likely reduces the offender's perception and awareness of consequences of their actions. Heavy drinking is associated with vulnerability to injury, marital discord, and domestic violence. Moderate drinkers are more frequently engaged in intimate violence than are light drinkers and abstainers, however generally it is heavy and/or binge drinkers who are involved in the most chronic and serious forms of aggression. Research found that factors that increase the likelihood of alcohol-related violence include difficult temperament, hyperactivity, hostile beliefs, history of family violence, poor school performance, delinquent peers, criminogenic beliefs about alcohol's effects, impulsivity, and antisocial personality disorder. The odds, frequency, and severity of physical attacks are all positively correlated with alcohol use. In turn, violence decreases after behavioral marital alcoholism treatment.

Methanol laced alcohol

Main articles: List of methanol poisoning incidents and Alcohol congener analysis

Outbreaks of methanol poisoning have occurred when methanol is used to lace moonshine (bootleg liquor). This is commonly done to bulk up the original product to gain profit. Because of its similarities in both appearance and odor to ethanol (the alcohol in beverages), it is difficult to differentiate between the two.

Methanol is a toxic alcohol. If as little as 10 mL of pure methanol is ingested, for example, it can break down into formic acid, which can cause permanent blindness by destruction of the optic nerve, and 30 mL is potentially fatal, although the median lethal dose is typically 100 mL (3.4 fl oz) (i.e. 1–2 mL/kg body weight of pure methanol). Reference dose for methanol is 2.0 mg/kg/day. Toxic effects take hours to start, and effective antidotes can often prevent permanent damage.

India has a thriving moonshine industry, and methanol-tainted batches have killed over 2,000 people in the last 3 decades.

Alternative routes of administration

Alternative methods of alcohol administration like alcohol enema, alcohol inhalation, vodka eyeballing, or using alcohol powder (which can be added to water to make an alcoholic beverage, or inhaled with a nebulizer), all carry significant health risks.

Binge drinking

Main article: Binge drinking

Binge drinking is a style of drinking that is popular in several countries worldwide, and overlaps somewhat with social drinking since it is often done in groups. The degree of intoxication however, varies between and within various cultures that engage in this practice. A binge on alcohol can occur over hours, last up to several days, or in the event of extended abuse, even weeks. Due to the long term effects of alcohol abuse, binge drinking is considered to be a major public health issue.

Binge drinking is more common in males, during adolescence and young adulthood. Heavy regular binge drinking is associated with adverse effects on neurologic, cardiac, gastrointestinal, hematologic, immune, and musculoskeletal organ systems as well as increasing the risk of alcohol induced psychiatric disorders. A US-based review of the literature found that up to one-third of adolescents binge-drink, with 6% reaching the threshold of having an alcohol-related substance use disorder. Approximately one in 25 women binge-drinks during pregnancy, which can lead to fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Binge drinking during adolescence is associated with traffic accidents and other types of accidents, violent behavior as well as suicide. The more often a child or adolescent binge drinks and the younger they are the more likely that they will develop an alcohol use disorder including alcoholism. A large number of adolescents who binge-drink also consume other psychotropic substances.

Emotional issues

In emotional self-regulation, some people turn to drugs such as alcohol. Drug use, an example of response modulation, can be used to alter emotion-associated physiological responses. For example, alcohol can produce sedative and anxiolytic effects. A 2013 study found that immature defense mechanisms are linked to placing a higher value on junk food, alcohol, and television.

There is a two-way street between loneliness and drinking. People who drink more than once a week tend to feel lonelier, according to a study on Japanese workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. On the other hand, feelings of loneliness can also lead people to drink more, as shown in a separate study. Loneliness is a major risk factor for depression and alcoholism.

Hurtful communication

Alcohol may cause hurtful communication.

Drunk dialing

Main article: Drunk dialingDrunk dialing refers to an intoxicated person making phone calls that they would not likely make if sober, often a lonely individual calling former or current love interests.

A 2021 study, that examined the relationship between drunk texting and emotional dysregulation, found a positive correlation. The findings suggest that interventions targeting emotional regulation skills may be beneficial.

In vino veritas

Main article: In vino veritasIn vino veritas is a Latin phrase that means 'in wine, there is truth', suggesting a person under the influence of alcohol is more likely to speak their hidden thoughts and desires.

Risky sexual behavior

Main article: Alcohol and sexSome studies have made a connection between hookup culture and substance use. Most students said that their hookups occurred after drinking alcohol. Frietas stated that in her study, the relationships between drinking and the party scene and between alcohol and hookup culture were "impossible to miss".

Studies suggest that the degree of alcoholic intoxication in young people directly correlates with the level of risky behavior, such as engaging in multiple sex partners.

In 2018, the first study of its kind, found that alcohol and caffeinated energy drinks is linked with casual, risky sex among college-age adults.

Sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancy

Alcohol intoxication is associated with an increased risk that people will become involved in risky sexual behaviors, such as unprotected sex. Both men, and women, reported higher intentions to avoid using a condom when they were intoxicated by alcohol.

Coitus interruptus, also known as withdrawal, pulling out or the pull-out method, is a method of birth control during penetrative sexual intercourse, whereby the penis is withdrawn from a vagina or anus prior to ejaculation so that the ejaculate (semen) may be directed away in an effort to avoid insemination. Coitus interruptus carries a risk of STIs and unintended pregnancy. This risk is especially high during alcohol intoxication because lowered sexual inhibition can make it difficult to withdraw in time.

Women with unintended pregnancies are more likely to smoke tobacco, drink alcohol during pregnancy, and binge drink during pregnancy, which results in poorer health outcomes. (See also: fetal alcohol spectrum disorder)

Female sex workers in low- and middle-income countries have high rates of harmful alcohol use, which is associated with increased risk of risky sexual behavior. A bargirl is involved in a transaction known as a bar fine, which is a fee paid by a customer to the operators of a bar or nightclub in East and Southeast Asia, allowing her to leave work early, typically to accompany a customer outside for sexual services. Screening carried out in the 1990s in Malawi, an African country, indicated that about 80 per cent of bargirls carried the HIV virus. Research carried out at the time indicated that economic necessity was a major consideration in engaging and persisting in sex work.

Societal damage

Alcohol causes a plethora of detrimental effects in society. A 2023 systematic review estimated the societal costs of alcohol use to be around 2.6% of the GDP. Many emergency room visits involve alcohol use. Alcohol availability and consumption rates and alcohol rates are positively associated with nuisance, loitering, panhandling, and disorderly conduct in public space.

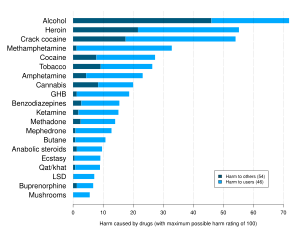

A 2011 study challenged the perception of heroin as the more dangerous substance. The research suggests, when considering the wider social, physical, and financial costs, alcohol may be more harmful.

Individuals who engage with or share alcohol-related content on social networking services tend to exhibit higher levels of alcohol use and related issues. Overwork is linked to an increased risk of unhealthy alcohol consumption. Also, unemployment can heighten the risk of alcohol consumption and smoking. As many as 15% of employees show problematic alcohol-related behaviors in the workplace, such as drinking before going to work or even drinking on the job.

College

Main article: Alcohol use among college studentsMany students attending colleges, universities, and other higher education institutions consume alcoholic beverages. The laws and social culture around this practice vary by country and institution type, and within an institution, some students may drink heavily whereas others may not drink at all. In the United States, drinking tends to be particularly associated with fraternities.

Alcohol abuse among college students refers to unhealthy alcohol drinking behaviors by college and university students. While the legal drinking age varies by country, the high number of underage students that consume alcohol has presented many problems and consequences for universities. The causes of alcohol abuse tend to be peer pressure, fraternity or sorority involvement, and stress. College students who abuse alcohol can suffer from health concerns, poor academic performance or legal consequences. Prevention and treatment include campus counseling, stronger enforcement of underage drinking or changing the campus culture.

Recent research indicates that the abundance of alcohol retailers and the availability of inexpensive alcoholic beverages are linked to heavy alcohol consumption among college students.

Poverty

Alcohol consumption can contribute to secondary poverty (where people fall back into poverty after escaping it). The Bureau of Labor Statistics found that "the average American consumer dedicates 1 percent of all their spending to alcohol".

Unsustainable tourism

Some popular tourist destinations, are cracking down on the impacts of tourism from excessive drinking. In an effort to promote a more sustainable tourism industry, these locations are implementing new regulations to curb binge drinking. This includes Llucmajor, Palma, Calvia (Magaluf) in Majorca and Sant Antoni in Ibiza, where late-night sales of alcohol will be banned. This comes after years of issues with rowdy tourists and the negative impacts it has on local residents.

Suicide

Most people are under the influence of sedative-hypnotic drugs (such as alcohol or benzodiazepines) when they die by suicide, with alcoholism present in between 15% and 61% of cases. Countries that have higher rates of alcohol use and a greater density of bars generally also have higher rates of suicide. About 2.2–3.4% of those who have been treated for alcoholism at some point in their life die by suicide. Alcoholics who attempt suicide are usually male, older, and have tried to take their own lives in the past. In adolescents who misuse alcohol, neurological and psychological dysfunctions may contribute to the increased risk of suicide.

Interactions

Disorders

COVID-19

A 2023 study suggests a link between alcohol consumption and worse COVID-19 outcomes. Researchers analyzed data from over 1.6 million people and found that any level of alcohol consumption increased the risk of severe illness, intensive care unit admission, and needing ventilation compared to non-drinkers. Even a history of drinking was associated with a higher risk of severe COVID-19. These findings suggest that avoiding alcohol altogether might be beneficial during the pandemic.

Diabetes

See the insulin section.

Hepatitis

Alcohol consumption can be especially dangerous for those with pre-existing liver damage from hepatitis B or C. Even relatively low amounts of alcohol can be life-threatening in these cases, so a strict adherence to abstinence is highly recommended.

Histamine intolerance

Alcohol may release histamine in individuals with histamine intolerance.

Mental disorders

Mental disorders can be a significant risk factor for alcohol abuse.

Alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, and alcoholism are comorbid with anxiety disorders. With dual diagnosis, the initial symptoms of mental illness tend to appear before those of substance abuse. Individuals with common mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, or phobias, are twice as likely to also report having an alcohol use disorder, compared to those without these mental health challenges. Alcohol is a major risk factor for self-harm. Individuals with anxiety disorders who self-medicate with drugs or alcohol may also have an increased likelihood of suicidal ideation.

-

Increased risk of developing alcohol dependency or abuse in individuals with a given mental health disorder relative to those without.

Increased risk of developing alcohol dependency or abuse in individuals with a given mental health disorder relative to those without.

Peptic ulcer disease

In patients who have a peptic ulcer disease (PUD), the mucosal layer is broken down by ethanol. PUD is commonly associated with the bacteria Helicobacter pylori, which secretes a toxin that weakens the mucosal wall, allowing acid and protein enzymes to penetrate the weakened barrier. Because alcohol stimulates the stomach to secrete acid, a person with PUD should avoid drinking alcohol on an empty stomach. Drinking alcohol causes more acid release, which further damages the already-weakened stomach wall. Complications of this disease could include a burning pain in the abdomen, bloating and in severe cases, the presence of dark black stools indicate internal bleeding. A person who drinks alcohol regularly is strongly advised to reduce their intake to prevent PUD aggravation.

Dosage forms

Alcohol induced dose dumping (AIDD)

Main article: Dose dumpingAlcohol-induced dose dumping (AIDD) is by definition an unintended rapid release of large amounts of a given drug, when administered through a modified-release dosage while co-ingesting ethanol. This is considered a pharmaceutical disadvantage due to the high risk of causing drug-induced toxicity by increasing the absorption and serum concentration above the therapeutic window of the drug. The best way to prevent this interaction is by avoiding the co-ingestion of both substances or using specific controlled-release formulations that are resistant to AIDD.

Drugs

See also: Poly drug useAlcohol can intensify the sedation caused by antipsychotics, and certain antidepressants.

Alcohol combined with cannabis (not to be confused with tincture of cannabis which contains minute quantities of alcohol) — known as cross-fading and may easily cause spins in people who are drunk and smoke potent cannabis; Ethanol increases plasma tetrahydrocannabinol levels, which suggests that ethanol may increase the absorption of tetrahydrocannabinol.

TOMSO is a lesser-known psychedelic drug and a substituted amphetamine. TOMSO was first synthesized by Alexander Shulgin. According to Shulgin's book PiHKAL, TOMSO is inactive on its own and requires consumption of alcohol to become active.

Hypnotics/sedatives

Alcohol can intensify the sedation caused by hypnotics/sedatives such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, sedative antihistamines, opioids, nonbenzodiazepines/Z-drugs (such as zolpidem and zopiclone).

Disulfiram-like drugs

Main article: Disulfiram-like drugDisulfiram

Disulfiram inhibits the enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, which in turn results in buildup of acetaldehyde, a toxic metabolite of ethanol with unpleasant effects. The medication or drug is commonly used to treat alcohol use disorder, and results in immediate hangover-like symptoms upon consumption of alcohol, this effect is widely known as disulfiram effect.

Metronidazole

Metronidazole is an antibacterial agent that kills bacteria by damaging cellular DNA and hence cellular function. Metronidazole is usually given to people who have diarrhea caused by Clostridioides difficile bacteria. Patients who are taking metronidazole are sometimes advised to avoid alcohol, even after 1 hour following the last dose. Although older data suggested a possible disulfiram-like effect of metronidazole, newer data has challenged this and suggests it does not actually have this effect.

Insulin

Alcohol consumption can cause hypoglycemia in diabetics on certain medications, such as insulin or sulfonylurea, by blocking gluconeogenesis.

NSAIDs

The concomitant use of NSAIDs with alcohol and/or tobacco products significantly increases the already elevated risk of peptic ulcers during NSAID therapy.

The risk of stomach bleeding is still increased when aspirin is taken with alcohol or warfarin.

Stimulants

Main articles: Caffeinated alcoholic drink, Coca wine, and Nicotini

Controlled animal and human studies showed that caffeine (energy drinks) in combination with alcohol increased the craving for more alcohol more strongly than alcohol alone. These findings correspond to epidemiological data that people who consume energy drinks generally showed an increased tendency to take alcohol and other substances.

Ethanol interacts with cocaine in vivo to produce cocaethylene, another psychoactive substance which may be substantially more cardiotoxic than either cocaine or alcohol by themselves.

Ethylphenidate formation appears to be more common when large quantities of methylphenidate and alcohol are consumed at the same time, such as in non-medical use or overdose scenarios. However, only a small percent of the consumed methylphenidate is converted to ethylphenidate.